This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Miss.Julie ^ ^ Email:[email protected] Skype:[email protected] Whatsapp:+8618872220730

Miss.Julie ^ _ ^ Email:[email protected] Skype:[email protected] Whatsapp:+8618872220730 Raw anabolic steroid hormone powders from China with high purity&safe delivery Powder list : Testosterone enanthate Testosterone cypionate Testosterone propionate Testosterone-Sustanon250 Testosterone phenylpropionate Testosterone Acetate Testosterone decanoate Testosterone-Base Testosterone Isocaproate Testosterone undecanoate 17a-Methyl-1-Testosterone Fluoxymesterone(Halotesin) Mesterolone(Proviron) Methyltestosterone Trenbolone Acetate Trenbolone enanthate Trenbolone Base Metribolone Trenbolone Hexahydrobenzyl Carbonate Nandrolone decanoate Nandrolone Propionate Nandrolone phenylpropionate Nandrolone Mestanolone Drostanolone enanthate Drostanolone propionate (Masteron) 17a-Methyl-Drostanolone (Methasterone) Boldenone undecylenate (EQ) Methenolone Acetate Methenolone Enanthate (primobolin) Boldenoe cypionate Boldenoe Acetate Methandrostenolone (Dianabol) Oxandrolone (Anavar) Oxymetholone (Anadrol) Stanozolol (Winstrol) Turinabol Clostebol Acetate Anastrozloe (Arimidex) Clomiphene Citrate(Clomid) Exemestane Letrozole (Femara) Mifepristone Tamoxifen Citrate Semi-finished Injectable / Oral steroids: Test prop-----------100mg/ml 200mg/ml Test enan-----------250mg/ml 300mg/ml 400mg/ml 500mg/ml 600mg/ml Test cyp------------200mg/ml 250mg/ml 300mg/ml Test Sustanon-------200mg/ml 250mg/ml 300mg/ml 400mg/ml Deca----------------200mg/ml 250mg/ml Equipoise-----------200mg/ml 300mg/ml Tren ace------------100mg/ml 200mg/ml Tren enan-----------100mg/ml -

New Zealand Data Sheet 1. Product Name

NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME SUSTANON 250 (250 mg testosterone esters solution for injection) (SUSTANON) TESTOSTERONE ESTERS 250mg/mL for injection Presentations that are not currently available The vials are currently not available 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Name and strength of the active substances - testosterone proprionate 30mg testosterone phenylpropionate 60mg testosterone isocaproate 60mg testosterone decanoate 100mg All four compounds are esters of the natural hormone testosterone. The total amount of testosterone per 1 mL is 176mg. List of excipients - 1 mL arachis oil and the solution also contains 10 per cent benzyl alcohol. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Oily solution for intramuscular use. A clear, pale yellow solution. Each clear glass ampoule or vial contains 1 mL in arachis oil. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Testosterone replacement therapy in males for conditions associated with primary and secondary hypogonadism, either congenital or acquired. In female to male transsexuals: • masculinization Moreover, in men testosterone therapy may be indicated in osteoporosis caused by androgen deficiency. 4.2 Dose and method of administration In general, the dose should be adjusted according to the response of the individual patient. Dose Adults (incl. elderly): Usually, one injection of 1ml per three weeks is adequate. Paediatric population: Safety and efficacy in children and adolescents, have not yet been established. Pre-pubertal children treated with SUSTANON should be treated with caution (see Warnings and Precautions). SUSTANON contains benzyl alcohol and is contraindicatedin children under 3 years of age. Method of administration SUSTANON should be administered by deep intramuscular injection. -

A28 Anabolic Steroids

Anabolic SteroidsSteroids A guide for users & professionals his booklet is designed to provide information about the use of anabolic steroids and some of the other drugs Tthat are used in conjunction with them. We have tried to keep the booklet free from technical jargon but on occasions it has proven necessary to include some medical, chemical or biological terminology. I hope that this will not prevent the information being accessible to all readers. The first section explaining how steroids work is the most complex, but it gets easier to understand after that (promise). The booklet is not intended to encourage anyone to use these drugs but provides basic information about how they work, how they are used and the possible consequences of using them. Anabolic Steroids A guide for users & professionals Contents Introduction .........................................................7 Formation of Testosterone ...............................................................8 Method of Action ..............................................................................9 How Steroids Work (illustration).......................................................10 Section 1 How Steroids are Used ....................................... 13 What Steroid? ................................................................................ 14 How Much to Use? ......................................................................... 15 Length of Courses? ........................................................................ 15 How Often to Use Steroids? -

Pdf 86.39 Kb

“Detection of Testosterone Esters in Blood Sample” Dr. G. Gmeiner, Dr. G. Forsdahl, Dr. Erceg (Seibersdorf Labor GmbH, Austria) Project Summary Testosterone is still regarded as the major contributor to steroid doping world-wide. Among the most common forms of application are injections of different sorts of esters. State-of-the-Art detection of Testosterone doping includes the quantification of the Testosterone /Epitestosterone – Ratio (T/E – ratio) as well as subsequent Isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS). Previous published studies of our research group have demonstrated that a comparably high percentage of testosterone preparations do not significantly differ from endogenous values of testosterone and markers of testosterone doping. Consequently when such preparations with endogenous – like 13CVPDB values are applied, IRMS - technology fails to detect testosterone doping. Direct detection of the testosterone ester leads to an unequivocal proof of doping with testosterone preparations, because such esters are not built endogenously. Previous studies indicate that a direct detection of testosterone esters in both hair and plasma is possible. Aim of the proposed project is the investigation and optimisation of the direct detection of testosterone esters in body fluids like serum, whole blood and stabilized blood with an already developed detection method using modern and sensitive technology. The project will gain information on diagnostic windows for detection of doping using testosterone esters and proper sampling conditions. Additional aim of the proposed project is to evaluate the suitability of already collected blood samples in doping control (e.g. samples collected for blood parameter measurement or growth hormone detection) for a possible reanalysis for testosterone esters. -

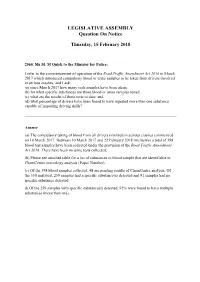

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Question on Notice

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Question On Notice Thursday, 15 February 2018 2560. Ms M. M Quirk to the Minister for Police; I refer to the commencement of operation of the Road Traffic Amendment Act 2016 in March 2017 which introduced compulsory blood or urine samples to be taken from drivers involved in serious crashes, and I ask: (a) since March 2017 how many such samples have been taken; (b) for what specific substances are those blood or urine samples tested; (c) what are the results of those tests to date; and (d) what percentage of drivers have been found to have ingested more than one substance capable of impairing driving skills? Answer (a) The compulsory taking of blood from all drivers involved in serious crashes commenced on 10 March 2017. Between 10 March 2017 and 22 February 2018 (inclusive) a total of 398 blood test samples have been collected under the provision of the Road Traffic Amendment Act 2016. There have been no urine tests collected. (b) Please see attached table for a list of substances in blood sample that are identifiable in ChemCentre toxicology analysis (Paper Number). (c) Of the 398 blood samples collected, 48 are pending results of ChemCentre analysis. Of the 350 analysed, 259 samples had a specific substance(s) detected and 91 samples had no specific substance detected. d) Of the 259 samples with specific substance(s) detected, 92% were found to have multiple substances (more than one). Detectable Substances in Blood Samples capable of identification by the ChemCentre WA. ACETALDEHYDE AMITRIPTYLINE/NORTRIPTYLINE -

WO 2012/148570 Al 1 November 2012 (01.11.2012) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/148570 Al 1 November 2012 (01.11.2012) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, A61L 27/14 (2006.01) A61P 17/02 (2006.01) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, C08L 101/16 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, (21) International Application Number: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, PCT/US20 12/027464 MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (22) International Filing Date: OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, 2 March 2012 (02.03.2012) SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (30) Priority Data: GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, 13/093,479 25 April 201 1 (25.04.201 1) US UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, WARSAW ORTHOPEDIC, INC. -

Influence of the Use of Testosterone Associated with Physical

original article Influence of the use of testosterone associated with physical training on some hematologic and physical parameters in older rats with alloxan-induced diabetes Romeu Paulo Martins Silva1,2, Rodrigo Otávio dos Santos2, Nelson Eurípedes Matildes Junior2, Antônio Vicente Mundim3, Mario da Silva Garrote-Filho3, Pâmella Ferreira Rodrigues2, Nilson Penha-Silva3 ABSTRACT 1 Centro de Ciências da Saúde e Objective: This study investigated the possible blood changes in wistar rats elderly with and without Desporto, Universidade Federal do treatment with anabolic steroids submitted physical training. Materials and methods: Elderly rats Acre (UFAC), Rio Branco, AC, Brasil (32) were divided into four groups: normal (N), treated normal (NT), diabetic (D) and treated diabetic 2 Centro Universitário do Planalto de (DT). They were submitted to 20 sessions of swimming with overload (5% body weight), 40 min/ Araxá (Uniaraxá), Araxá, MG, Brasil 3 Instituto de Genética e Bioquímica, day for four weeks. The NT and DT groups received application of testosterone twice a week. At Universidade Federal de Uberlândia the end of the sessions, the animals were subjected to swimming until exhaustion and then killed (UFU), Uberlândia, MG, Brasil for removal of blood and visceral fat. We evaluated maximum swim time, weight of visceral fat, erythrogram, leukogram, lipidogram and serum levels of glucose, lactate, aspartate aminotransferase Correspondence to: and creatine kinase. The results were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc Romeu Paulo Martins Silva Tukey test. Results: In elderly diabetic rats, the use of anabolic associated with physical training in Universidade Federal do Acre Instituto de Genética e Bioquímica older rats resulted in improvement in erythrogram, lipidogram and physical performance for high- BR 364, km 04 intensity aerobic exercise. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0101517 A1 De Nijs Et Al

US 2005O1 O1517A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2005/0101517 A1 De Nijs et al. (43) Pub. Date: May 12, 2005 (54) NOVELTESTOSTERONE ESTER (86) PCT No.: PCT/EP01/09569 FORMULATION FOR HUMAN USE (30) Foreign Application Priority Data (76) Inventors: Henrick De Nijs, XC Oss (NL); Wendy Margaretha KerSmaekers, RB Aug. 23, 2000 (EP) - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - OO2O2939.5 Nijmegen (NL); Stepanus Cornelis O O Schutte, EJ Oosterbeek (NL); Johann Publication Classification Gerhard Cornelis Van Bruggen, EN 7 Waalwijk (NL) (51) Int. Cl." ..................................................... A61K 31/00 (52) U.S. Cl. .................................................................. 514/1 Correspondence Address: AKZO NOBEL PHARMA PATENT (57) ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT Disclosed is a formulation of testosterone decanoate for use PO BOX 3.18 in the treatment of humans. In contrast with known formu MILLSBORO, DE 19966 (US) lations comprising testosterone decanoate, it was found that any other esters of testosterone normally present together (21) Appl. No.: 10/362,350 with testosterone decanoate, can be omitted and the formu lation thus comprises testosterone decanoate as the Sole ester (22) PCT Filed: Aug. 17, 2001 of testosterone. Patent Application Publication May 12, 2005 US 2005/0101517 A1 Iain?l? US 2005/0101517 A1 May 12, 2005 NOVELTESTOSTERONE ESTER FORMULATION in which the compound is generally included in a broad FOR HUMAN USE range of Summed-up esters of testosterone. In Some patent documents originating from the seventies (BE 855163, U.S. FIELD OF THE INVENTION Pat. No. 4,220,599 (DE 2508615), U.S. Pat. No. 4,071,623) testosterone esters of a chain length typically including 0001) The invention is in the field of the treatment of decanoate are disclosed for oral administration. -

Androgen Deficiency

Androgen Deficiency The GP’s role Diagnosis GPs are generally the first point of contact for men with Medical history symptoms of androgen deficiency. • Undescended testes. GPs are relied upon for clinical and laboratory examinations, • Testicular surgery. appropriate referral, and ongoing patient management. • Pubertal development or virilisation. Patient referral to an endocrinologist, urologist or sexual • Fertility. health specialist is required for PBS-subsidised testosterone prescriptions. • Genitourinary infection. • Coexistent illness (e.g. pituitary disease, thalassaemia, Condition overview haemochromatosis). • Sexual function (all men presenting with erectile dysfunction Androgen deficiency is a syndrome caused by poor testicular should be assessed for androgen deficiency, even though function (hypogonadism), resulting from either primary it is an uncommon cause). (testicular) or secondary (hypothalamic-pituitary) disease, • Drug use (medical or recreational). and is characterised by a low testosterone level accompanied by signs and symptoms1, 2, 3. Clinical examination and assessment It is estimated that approximately 5 in 1000 men have androgen Prepubertal onset 4 deficiency warranting treatment with testosterone . • Micropenis. A low testosterone level alone does not constitute androgen • Small testes. deficiency5, and neither does the normal age-related decline in testosterone (of approximately 1% annually6). Peripubertal onset Androgen deficiency may have subtle effects on health and • Delayed or incomplete sexual and somatic maturation. wellbeing, which can make diagnosis challenging. • Small testes. • Attenuated penile enlargement. Causes • Attenuated pigmentation of scrotum. • Attenuated laryngeal development. Primary hypogonadism • Attenuated growth of facial, body and pubic hair. • Chromosomal (e.g. Klinefelter syndrome (the most common • Poor muscle development. cause of androgen deficiency)). • Gynecomastia. • Undescended testes. • Trauma. Postpubertal onset • Infection (e.g. -

1 Document Title General Guidelines for the Use of Hormone Treatment

General Guidelines For The Use Of Hormone Treatment In Document Title Gender Dysphoria Northern Region Gender Dysphoria Service Dr Helen Greener, Consultant in Gender Dysphoria & Clinical Lead Author Lead Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust Dr Deborah Beere, Consultant in Gender Dysphoria Dr Anna Laws, Clinical Psychologist in Gender Dysphoria Dr Michael Shaw, Consultant in Gender Dysphoria Dr Ewa Wisniewska Young, Consultant in Gender Dysphoria Mary Soulsby, Specialist Nurse in Gender Dysphoria Harrogate District Hospital Contributors Dr Peter Hammond, Consultant Endocrinologist Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Dr Richard Quinton, Consultant Endocrinologist NHS North of England Commissioning Support Unit Helen Seymour, Senior Medicines Optimisation Pharmacist NHS North Tyneside Clinical Commissioning Group Dr Ruth Evans, Medical Director (General Practitioner) Completion date November 2020 Sunderland and South Tyneside Area Prescribing Committee – 3 February 2021 Durham and Tees Valley Area Prescribing Committee – 11 Ratified by March 2021 North of Tyne, Gateshead and North Cumbria Area Prescribing Committee – 13 April 2021 Review Date February 2024 Version number 1 This document supersedes: Guidelines For The Use Of Masculinising Hormone Therapy In Gender Dysphoria: Information for Primary Care November 2014 Guidelines For The Use Of Feminising Hormone Therapy In Gender Dysphoria: Information for Primary Care July 2014 (Minor update November 2014) 1 General Guidelines For The Use Of Hormone -

Effects of Testosterone Levels on Mortality and Cardiovascular Risk

Effects of Testosterone Levels on Mortality and Cardiovascular Risk in Men with Type 2 Diabetes Thesis submitted to The University of Sheffield For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Vakkat Muraleedharan Department of Oncology and Metabolism University of Sheffield Medical School September 2018 1 Contents Page List of figures 12 List of tables 17 Summary of findings 20 Acknowledgements 22 Publications and presentations arising from the thesis 24 Schematic representation of studies conducted over the course of PhD and personnel 30 contribution to each section Chapter One 31 General Introduction 1.1 Introduction 31 1.2. Testosterone and mortality 40 1.2.1 Population or community studies 40 1.2.2 Studies in specific disease populations 44 1.3. Relationship of testosterone to cardiovascular mortality and morbidity 46 1.4 Testosterone and mortality in renal disease 50 1.5 Metabolic syndrome, diabetes, cardio-metabolic markers and 51 testosterone 1.5.1. Metabolic syndrome 51 1.5.2. Testosterone in the metabolic syndrome diabetes and insulin 54 resistance 1.5.3. Effect of androgen suppression on metabolic syndrome, type 2 60 diabetes and cardiovascular risk profile 1.5.4. The role of testosterone in dyslipidaemia, hypertension and 62 atherosclerosis 2 1.6. Role of androgen receptor in diabetes, obesity and metabolic 66 syndrome 1.6.1. The androgen receptor and androgen receptor gene 66 1.6.2. The androgen receptor CAG (AR CAG) repeat polymorphism 68 1.6.3. Clinical correlations of the AR CAG polymorphism in men 69 1.7 Testosterone replacement therapy 70 1.7.1. Effect of Testosterone replacement therapy on glycaemic control, 71 insulin resistance and lipid profile 1.7.2. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,911,773 B2 Kimball (45) Date of Patent: *Dec

US00891. 1773B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,911,773 B2 Kimball (45) Date of Patent: *Dec. 16, 2014 (54) PEELABLE POUCH FORTRANSDERMAL (56) References Cited PATCH AND METHOD FOR PACKAGING U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS (71) Applicant: Watson Laboratories, Inc., Salt Lake 2.954,116 A 9, 1960 Maso et al. City, UT (US) 2,998,880 A 9, 1961 Ladd 3.057467 A 10, 1962 Williams 3,124,825. A 3, 1964 Iovenko (72) Inventor: Michael W. Kimball, Salt Lake City, UT 3,152,515 A 10, 1964 Land (US) 3,152,694 A 10, 1964 Nashed et al. 3,186,869 A 6, 1965 Friedman (73) Assignee: Watson Laboratories, Inc., Salt Lake 3,217,871 A 11/1965 Lee 3,403,776 A 10/1968 Denny City, UT (US) 3,478,868 A 1 1/1969 Nerenberg et al. 3,552,638 A 1/1971 Quackenbush (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 3,563,371 A 2, 1971 Heinz patent is extended or adjusted under 35 3,616,898 A 11/1971 Massie U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 3,708, 106 A 1/1973 Sargent 3,847,280 A 11/1974 Poncy This patent is Subject to a terminal dis 3,913,789 A 10, 1975 Miller claimer. 3,926,311 A 12/1975 Laske 3,937,396 A 2f1976 Schneider 3,995,739 A 12/1976 Tasch et al. (21) Appl. No.: 14/090,502 4,279.344 A 7/1981 Holloway, Jr. 4.410,089 A 10, 1983 Bortolani 4,552,269 A 1 1/1985 Chang (22) Filed: Nov.