Landmarks Preservation Commission August 14, 2007, Designation List 395 LP-2237

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swimming Pools Are Factored Into the City of St

REGULATIONS What you’ll need: City of St. Clair Shores All pools, hot tubs and spas are to be installed • Building permit application. in accordance with the 2015 International Swimming Pool and Spa Code (ISPSC). • 2 sets of plans accurately showing dimensions of the pool, distances Swimming Permits are required for any pool capable of to the property lines and existing holding 24 inches or more of water (or for any buildings, existing building pond 12 inches or more deep). locations, electrical wire location Pools and indicate fence enclosure. (see Pools are not considered accessory structures, sample) but must be located in the rear yard & be at • Pool brochure or a drawing least 6 ft from the side & rear property lines. showing a cross-sectional view. There must be a distance of 4 feet between • $50 deposit (although based on the outside pool wall and any building located job cost, total permit fee usually on the same lot. totals $120). • Soil erosion permit may be All pools are to be provided with a filtration required for in-ground pool. Our system adequate to keep water clean & free of foreign matter. Anti-suction device required engineering department to review for filter. and determine. Plan Review All electrical installations shall comply with the Your application & drawings will go Permit instructions for 2015 Michigan Residential Code. Electrical permits & inspections are required. through a plan review process where pools, hot tubs and spas. several different inspectors and Underground wiring for pool shall be a departments make sure the pool you St. Clair Shores does not enforce minimum of 5-ft from pool. -

Garden Guide and Walking Tour Welcome to Greenwood Gardens, the 28-Acre Historic Garden Oasis Located in Short Hills, New Jersey

garden guide and walking tour welcome to greenwood gardens, the 28-acre historic garden oasis located in Short Hills, New Jersey. We invite you to take a self-guided tour through this enchanted hideaway, graced with terraced gardens, Arts and Crafts follies, stately fountains, hidden grottoes, romantic woodlands, and winding paths. Designed in the early 20th century, Greenwood offers visitors a peaceful haven in which to connect with nature, set against a backdrop of startling beauty and the artifacts of unique family history. DURING THIS TIME OF COVID-19, YOUR SAFETY IS OF GREATEST CONCERN TO US. PLEASE BE SURE TO: • Wear a face-covering • Maintain a six (6)-foot distance from other visitors TO ENSURE A SAFE AND PLEASANT VISIT PLEASE OBSERVE THE FOLLOWING RULES OF GARDEN ETIQUETTE: • Wear a face-covering. • Use of photography equipment is limited to cell • Maintain a six (6)-foot distance from other phones and pocket-sized cameras only. visitors. • Keep cell phones in silent mode so all visitors can • The only animals permitted in the garden are enjoy our quiet oasis. certified service animals. • Bicycles and scooters are not permitted. • Strollers are not permitted in the garden; stroller • No food or beverages, except for personal water parking is available on the East Terrace. bottles, are permitted on-site. • At all times, children must be accompanied by an • Remove all personal trash when you depart. adult. • At all times, clothing and shoes must be worn. PLEASE REFRAIN FROM THE FOLLOWING • Formal posed photography • Tree climbing • Playing audible music • Obstructing pathways • Feeding, chasing, or provoking wildlife • Flying drones • Entering ponds or water features • Picnicking in the garden • Smoking • Entering areas that are roped off • Blankets, chairs, and sunbathing • Making fires • Picking flowers • Drinking alcohol • Event gathering • Entering or disturbing plant beds • Playing active sports ACCESSIBILITY The restored Main Terrace with partial views of the Garden is accessible to all visitors. -

Safety Barrier Guidelines for Residential Pools Preventing Child Drownings

Safety Barrier Guidelines for Residential Pools Preventing Child Drownings U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission This document is in the public domain. Therefore it may be reproduced, in part or in whole, without permission by an individual or organization. However, if it is reproduced, the Commission would appreciate attribution and knowing how it is used. For further information, write: U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission Office of Communications 4330 East West Highway Bethesda, Md. 20814 www.cpsc.gov CPSC is charged with protecting the public from unreasonable risks of injury or death associated with the use of the thousands of consumer products under the agency’s jurisdiction. Many communities have enacted safety regulations for barriers at resi- dential swimming pools—in ground and above ground. In addition to following these laws, parents who own pools can take their own precau- tions to reduce the chances of their youngsters accessing the family or neighbors’ pools or spas without supervision. This booklet provides tips for creating and maintaining effective barriers to pools and spas. Each year, thousands of American families suffer swimming pool trage- dies—drownings and near-drownings of young children. The majority of deaths and injuries in pools and spas involve young children ages 1 to 3 and occur in residential settings. These tragedies are preventable. This U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) booklet offers guidelines for pool barriers that can help prevent most submersion incidents involving young children. This handbook is designed for use by owners, purchasers, and builders of residential pools, spas, and hot tubs. The swimming pool barrier guidelines are not a CPSC standard, nor are they mandatory requirements. -

Residential Swimming Pools

Florida Building Code Advanced Training: Residential Swimming Pools Florida Building Commission Department of Community Affairs 2555 Shumard Oak Boulevard Tallahassee, FL 32399-2100 (850) 487-1824 http://www.floridabuilding.org This presentation, developed by the Florida Swimming Pool Association in conjunction with Roy Lenois, Artesian Pools of East Florida, Inc., reflects private swimming pool-related provisions of the Florida Building Code, Residential and the Florida Building Code, Building as of October 1, 2005. Where section numbers are different in the slide from the notes section, identical code can be found in either document. Note that this presentation is arranged primarily from the viewpoint of the inspector. FBC Advanced Training: Residential Swimming Pools 1 Chapter 1: Administration Residential Code Chapter 41 of the Florida Building Code, Residential and Chapter 4 of the Building Code, Building provide code requirements for residential swimming pools. The language in both chapters is the same with the exception that Chapter 4 of the Building Code, Building is more inclusive. R101.2 Scope:…Construction standards or practices which are not covered by this code shall be in accordance with the provisions of Florida Building Code, Building. R101.2 Scope. The provisions of the Florida Building Code, Residential shall apply to the construction, alteration, movement, enlargement, replacement, repair, equipment, use and occupancy, location, removal and demolition of detached one- and two-family dwellings and multiple single-family dwellings (townhouses) not more than three stories in height with a separate means of egress and their accessory structures. Construction standards or practices which are not covered by this code shall be in accordance with the provisions of Florida Building Code, Building. -

Take Advantage of Dog Park Fun That's Off the Chain(PDF)

TIPS +tails SEPTEMBER 2012 Take Advantage of Dog Park Fun That’s Off the Chain New York City’s many off-leash dog parks provide the perfect venue for a tail-wagging good time The start of fall is probably one of the most beautiful times to be outside in the City with your dog. Now that the dog days are wafting away on cooler breezes, it may be a great time to treat yourself and your pooch to a quality time dedicated to socializing, fun and freedom. Did you know New York City boasts more than 50 off-leash dog parks, each with its own charm and amenities ranging from nature trails to swimming pools? For a good time, keep this list of the top 25 handy and refer to it often. With it, you and your dog will never tire of a walk outside. 1. Carl Schurz Park Dog Run: East End Ave. between 12. Inwood Hill Park Dog Run: Dyckman St and Payson 24. Tompkins Square Park Dog Run: 1st Ave and Ave 84th and 89th St. Stroll along the East River after Ave. It’s a popular City park for both pooches and B between 7th and 10th. Soft mulch and fun times your pup mixes it up in two off-leash dog runs. pet owners, and there’s plenty of room to explore. await at this well-maintained off-leash park. 2. Central Park. Central Park is designated off-leash 13. J. Hood Wright Dog Run: Fort Washington & 25. Washington Square Park Dog Run: Washington for the hours of 9pm until 9am daily. -

National Center on Accessibility Swimming Pool Accessibility Project

National Center on Accessibility Indiana University School of Health, Physical Education & Recreation Department of Recreation & Park Administration Swimming Pool Accessibility ATBCB Award Number: QA95007001 RECOMMENDATIONS & PRODUCT INFORMATION September 1996 Edward J. Hamilton, Ph.D. Kathy Mispagel Raymond Bloomer Submitted to: U.S. Architectural & Transportation Barriers Compliance Board Swimming Pool Accessibility Project PROJECT OFFICER Peggy Greenwell U.S. Architectural & Transportation Barriers Compliance Board PROJECT STAFF National Center on Accessibility Project Director Research Assistant Edward J. Hamilton, Ph.D. Kathy Mispagel Technical Advisors Project Secretaries Ray Bloomer Jennifer Rekers Jennifer Bowerman Shani Asher Gary Robb Debbie Lane PROJECT CONSULTANT Peter Axelson Beneficial Designs, Inc. PROJECT ADVISORY PANEL Kim Beasly, AJA Tom Riegelman Paralyzed Veterans of America Hyatt Hotel Corporation Josh Brener Bruce Oka Water Technology United Cerebral Palsy Association Lew Daly Steve Spinetto Triad Technologies, Inc. Boston Mayor's Commission on People with Disabilities Walter Johnson NRPA Regional Director Kenneth Ward Councilman, Hunsacker & Assoc. Jim Kacius, AJA Browning, Day, Mullins, Rick Webster and Dierdorf, Inc. Center for Independent Living Keith Krumbeck Gene Wells Spectrum Aquarius Pools Louise Priest Kent Williams Ellis & Associates Professional Pool Operators National Center on Accessibility Swimming Pool Accessibility Project Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................... -

Report Measures the State of Parks in Brooklyn

P a g e | 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 2 Methodology Page 2 Park Breakdown Page 5 Multiple/No Community District Jurisdictions Page 5 Brooklyn Community District 1 Page 6 Brooklyn Community District 2 Page 12 Brooklyn Community District 3 Page 18 Brooklyn Community District 4 Page 23 Brooklyn Community District 5 Page 26 Brooklyn Community District 6 Page 30 Brooklyn Community District 7 Page 34 Brooklyn Community District 8 Page 36 Brooklyn Community District 9 Page 38 Brooklyn Community District 10 Page 39 Brooklyn Community District 11 Page 42 Brooklyn Community District 12 Page 43 Brooklyn Community District 13 Page 45 Brooklyn Community District 14 Page 49 Brooklyn Community District 15 Page 50 Brooklyn Community District 16 Page 53 Brooklyn Community District 17 Page 57 Brooklyn Community District 18 Page 59 Assessment Outcomes Page 62 Summary Recommendations Page 63 Appendix 1: Survey Questions Page 64 P a g e | 2 Introduction There are 877 parks in Brooklyn, of varying sizes and amenities. This report measures the state of parks in Brooklyn. There are many different kinds of parks — active, passive, and pocket — and this report focuses on active parks that have a mix of amenities and uses. It is important for Brooklynites to have a pleasant park in their neighborhood to enjoy open space, meet their neighbors, play, and relax. While park equity is integral to creating One Brooklyn — a place where all residents can enjoy outdoor recreation and relaxation — fulfilling the vision of community parks first depends on measuring our current state of parks. This report will be used as a tool to guide my parks capital allocations and recommendations to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks), as well as to identify recommendations to improve advocacy for parks at the community and grassroots level in order to improve neighborhoods across the borough. -

Lufkin and Jefferson Pool Assessments

2013 FACILITY EVALUATION Date: 24 September 2013 TO: Village of Villa Park Greg Gola, CPRP Director of Parks and Recreation Marlon Hummell Superintendent of Parks, Buildings & Grounds PROJECT NAME: Facility Evaluation Lufkin & Jefferson Pools WA PROJECT NUMBER: 2013-010 ____ Village of Villa Park Parks & Recreation / Outdoor Aquatics Facility Evaluation / 24 September 2013 / Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS FACILITY EVALUTION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... 3 SCOPE ........................................................................................................... 3 HISTORY ....................................................................................................... 3 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................... 3 OBSERVATIONS ........................................................................................... 4 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................. 4 LUFKIN POOL OBSERVATIONS ........................................................................ 7 MAIN POOL ................................................................................................... 7 SPRAY AREA ............................................................................................... 13 MAIN POOL MECHANICAL .......................................................................... 14 SITE ........................................................................................................ -

Guide to the Betsy Head Farm Garden Photo Collection, BCMS.0001 Finding Aid Prepared by Alla Roylance

Guide to the Betsy Head Farm Garden Photo Collection, BCMS.0001 Finding aid prepared by Alla Roylance This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 27, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Betsy Head Farm Garden Photo Collection, BCMS.0001 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 5 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 7 Series I: Lantern Slides.......................................................................................................................... -

2006 - 2007 Report Front Cover: Children Enjoying a Summer Day at Sachkerah Woods Playground in Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx

City of New York Parks & Recreation 2006 - 2007 Report Front cover: Children enjoying a summer day at Sachkerah Woods Playground in Van Cortlandt Park, Bronx. Back cover: A sunflower grows along the High Line in Manhattan. City of New York Parks & Recreation 1 Daffodils Named by Mayor Bloomberg as the offi cial fl ower of New York City s the steward of 14 percent of New York City’s land, the Department of Parks & Recreation builds and maintains clean, safe and accessible parks, and programs them with recreational, cultural and educational Aactivities for people of all ages. Through its work, Parks & Recreation enriches the lives of New Yorkers with per- sonal, health and economic benefi ts. We promote physical and emotional well- being, providing venues for fi tness, peaceful respite and making new friends. Our recreation programs and facilities help combat the growing rates of obesity, dia- betes and high blood pressure. The trees under our care reduce air pollutants, creating more breathable air for all New Yorkers. Parks also help communities by boosting property values, increasing tourism and generating revenue. This Biennial Report covers the major initiatives we pursued in 2006 and 2007 and, thanks to Mayor Bloomberg’s visionary PlaNYC, it provides a glimpse of an even greener future. 2 Dear Friends, Great cities deserve great parks and as New York City continues its role as one of the capitals of the world, we are pleased to report that its parks are growing and thriving. We are in the largest period of park expansion since the 1930s. Across the city, we are building at an unprecedented scale by transforming spaces that were former landfi lls, vacant buildings and abandoned lots into vibrant destinations for active recreation. -

Mccarren Park Uart View All Monuments in NYC Parks, As Well As Temporary Public Art Installations on Our NYC Public Art Map and Guide I Map)

BOARD MEETING AFFIRMATION OF NEW MEMBERS Chairperson Ms. Fuller requested the new members to come forward to be affirmed. Mr. Solomon Green, Ms. Dana Rachlin, Mr. Michael Gary Schlesinger ROLL CALL Chairperson Ms. Fuller requested District Manager Mr. Esposito to call the roll. He informed the Chairperson that there were 39 members present, a sufficient quorum to call the meeting to order. MOMENT OF SILENCE Chairperson Ms. Fuller called for a moment of silence dedicated to Mr. Weidberg and his family, for the passing of Mr. Weidberg’s brother. ELECTIONS At 8:00 PM, Chairperson Ms. Fuller announced that it was time for elections. She requested the Elections Committee members [Ms. Barros; Ms. Foster; Mr. Torres] to come forward. Ballots were distributed and collected. The meeting continued while the Elections Committee convened in the other room to count the ballots. The committee reported the following regarding the elections: EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE POSITION CANDIDATE TALLY OF VOTES Chairperson Dealice Fuller 38 votes __________________________________________________________________________________ First Vice Chairperson Simon Weiser 23 votes. Karen Nieves 14 votes. __________________________________________________________________________________ Second Vice Chairperson Del Teague 38 votes. __________________________________________________________________________________ Third Vice Chairperson Stephen J. Weidberg 38 votes. __________________________________________________________________________________ Financial Secretary Maria Viera -

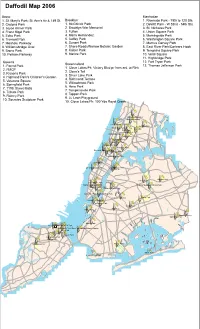

Daffodil Map 2006

Daffodil Map 2006 Bronx Manhattan 1. St. Mary's Park; St. Ann's Av & 149 St. Brooklyn 1. Riverside Park - 79th to 120 Sts. 2. Crotona Park 1. McGolrick Park 2. DeWitt Park - W 52nd - 54th Sts. 3. Joyce Kilmer Park 2. Brooklyn War Memorial 3. St. Nicholas Park 4. Franz Sigel Park 3. Fulton 4. Union Square Park 5. Echo Park 4. Maria Hernandez 5. Morningside Park 6. Tremont Park 5. Coffey Park 6. Washington Square Park 7. Mosholu Parkway 6. Sunset Park 7. Marcus Garvey Park 8. Williamsbridge Oval 7. Shore Roads/Narrow Botanic Garden 8. East River Park/Corlears Hook 9. Bronx Park 8. Kaiser Park 9. Tompkins Square Park 10. Pelham Parkway 9. Marine Park 10. Verdi Square 11. Highbridge Park Queens 12. Fort Tryon Park Staten Island 1. Forest Park 13. Thomas Jefferson Park 1. Clove Lakes Pk; Victory Blvd pr from ent. to Rink 2. FMCP 2. Clove's Tail 3. Kissena Park 3. Silver Lake Park 4. Highland Park's Children's Garden 4. Richmond Terrace 5. Veterans Square 5. Willowbrook Park 6. Springfield Park 6. Hero Park 7. 111th Street Malls 7. Tompkinsville Park 8. Tribute Park 8. Tappen Park 9. Rainey Park 9. Lt. Leah Playground 10. Socrates Sculpture Park 10. Clove Lakes Pk: 100 Yds Royal Creek Williamsbridge Oval Mosholu Parkway Fort Tryon Park Pelham Pkwy Highbridge Park Bronx Park Echo Park Tremont Park Highbridge Park Crotona Park Joyce Kilmer Park Franz Sigel Park St Nicholas Park St Mary's Park Riverside PMaorkrningside Park Marcus Garvey Park Thomas Jefferson Park Verdi Square De Witt Clinton Park Socrates Sculpture Garden Rainey Park Kissena Park 111th Street Malls Union Square Park Washington Square Park Flushing Meadows Corona Park Tompkins Square Park Monsignor Mcgolrick Park East River Park/Corlears Hook Park Maria Hernandez Park Forest Park Brooklyn War Memorial Fort Greene Park Highland Park Coffey Park Fulton Park Veterans Square Springfield Park Sunset Park Richmond TLetr.ra Nceicholaus Lia Plgd.