Descriptive Metadata in the Music Industry 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ho Li Day Se Asons and Va Ca Tions Fei Er Tag Und Be Triebs Fe Rien BEAR FAMILY Will Be on Christmas Ho Li Days from Vom 23

Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 12. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 12th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 12. Janu ar 2004 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken day 12th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - wir uns für die gute Zusam menar beit im ver gange nen mers for their co-opera ti on in 2003. It has been a Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY...............................2 BEAT, 60s/70s.........................66 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. ........................19 SURF ........................................73 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER ..................22 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY .......................75 WESTERN .....................................27 BRITISH R&R ...................................80 C&W SOUNDTRACKS............................28 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT ........................80 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ......................28 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND ...............29 POP ......................................82 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE .................30 POP INSTRUMENTAL ............................90 -

May 16, 2014 WFAN's BOOMER & CARTON TEAM

May 16, 2014 WFAN’S BOOMER & CARTON TEAM UP WITH GIN BLOSSOMS ON MAY 23 FOR THE ‘SUMMER KICKOFF PARTY’ AT D’JAIS IN BELMAR, NEW JERSEY WFAN-AM/FM is counting down the days to summer and planning an exciting celebration to kick it off in style, with a live broadcast from morning show hosts Boomer & Carton at D’JAIS on Ocean Avenue in Belmar, New Jersey. Next Friday, May 23, Boomer Esiason & Craig Carton will host their inaugural Memorial Day “Summer Kickoff Party” with a live broadcast from 6AM – 10AM. In addition, there will be live performances by the GRAMMY® nominated band Gin Blossoms and special guests on-air during the show. Admission to the public is free, and the WFAN fan van crew will be on hand with giveaways. Tune in to WFAN on-air, streaming online at www.wfan.com and through the Radio.com app for mobile devices to hear Boomer & Carton and Gin Blossoms live from D’JAIS. Boomer & Carton – Broadcast on-air and online from 6 a.m. – 10 a.m. ET and simulcast on CBS Sports Network, the show features former NFL quarterback Boomer Esiason and radio veteran Craig Carton discussing New York sports talk with sports icons, league personnel, and a variety of national celebrities from the entertainment and music industries. For more than two decades, Gin Blossoms have defined the sound of jangle pop. From their late 80s start as Arizona’s top indie rock outfit, the Tempe-based combo has drawn critical applause and massive popular success for their trademark brand of chiming guitars, introspective lyricism, and irresistible melodies. -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

The Kid3 Handbook

The Kid3 Handbook Software development: Urs Fleisch The Kid3 Handbook 2 Contents 1 Introduction 11 2 Using Kid3 12 2.1 Kid3 features . 12 2.2 Example Usage . 12 3 Command Reference 14 3.1 The GUI Elements . 14 3.1.1 File List . 14 3.1.2 Edit Playlist . 15 3.1.3 Folder List . 15 3.1.4 File . 16 3.1.5 Tag 1 . 17 3.1.6 Tag 2 . 18 3.1.7 Tag 3 . 18 3.1.8 Frame List . 18 3.1.9 Synchronized Lyrics and Event Timing Codes . 21 3.2 The File Menu . 22 3.3 The Edit Menu . 28 3.4 The Tools Menu . 29 3.5 The Settings Menu . 32 3.6 The Help Menu . 37 4 kid3-cli 38 4.1 Commands . 38 4.1.1 Help . 38 4.1.2 Timeout . 38 4.1.3 Quit application . 38 4.1.4 Change folder . 38 4.1.5 Print the filename of the current folder . 39 4.1.6 Folder list . 39 4.1.7 Save the changed files . 39 4.1.8 Select file . 39 4.1.9 Select tag . 40 The Kid3 Handbook 4.1.10 Get tag frame . 40 4.1.11 Set tag frame . 40 4.1.12 Revert . 41 4.1.13 Import from file . 41 4.1.14 Automatic import . 41 4.1.15 Download album cover artwork . 42 4.1.16 Export to file . 42 4.1.17 Create playlist . 42 4.1.18 Apply filename format . 42 4.1.19 Apply tag format . -

Being Mother, Academic, & Wife: an Interpretive Inquiry

University of Alberta Being Mother, Academic, & Wife: An Interpretive Inquiry by Danielle Leigh Fullerton A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Counselling Psychology Department of Educational Psychology Edmonton, Alberta Spring 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-55349-7 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-55349-7 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Songkong for Melco

Digital Music Metadata SongKong Music Tagger Automatically managing your music metadata Digitized Music Library - Problems • Different mechanisms used to rip or download music • Music stored in different audio formats • Music collections much larger than before • Quality of original metadata varies considerably • No comprehensive metadata standard • Manually adding metadata very time consuming • Impossible to keep metadata consistent as add to collection SongKong - Concept • Should be possible to automatch and add metadata for majority of music collection easily • Need to apply consistency over collection, and keep consistent • Fix metadata within files so customer not tied to a particular music player (iTunes/Roon, Naim Wav Metadata) • Need rich comprehensive metadata, simple album/artist/title not enough • But need to give customer enough control because there is no such thing as a single one-fit metadata solution • Music collections are valuable and personal so we need • An audit of what has changed • Ability to undo changes if we don’t like them SongKong Music Tagger Installation • Available for: • Windows • MacOS • Linux • Synology Disk Station • Qnap Nas • Melco N1 Audio Server • Desktop and Remote interface for Windows/MacOS, Linux Desktop • Remote Web Interface for others so can be controlled from web browser even on iPad or phone Three steps to Improved Metadata 1. Select your Music folder and Run Fix Songs task. 2. Review the Options, then press Start 3. Wait for completion, detailed report shows exactly what has changed 1. Select your Music folder and Run Fix Songs task 2. Review any Options, e.g Basic Options Format Options (Desktop view) Classical Options (Web Browser View) . -

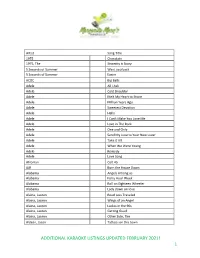

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist

Donna Haraway, "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist- Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century," in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York; Routledge, 1991), pp.149-181. AN IRONIC DREAM OF A COMMON LANGUAGE FOR WOMEN IN THE INTEGRATED CIRCUIT This chapter is an effort to build an ironic political myth faithful to feminism, socialism, and materialism. Perhaps more faithful as blasphemy is faithful, than as reverent worship and identification. Blasphemy has always seemed to require taking things very seriously. I know no better stance to adopt from within the secular-religious, evangelical traditions of United States politics, including the politics of socialist feminism. Blasphemy protects one from the moral majority within, while still insisting on the need for community. Blasphemy is not apostasy. Irony is about contradictions that do not resolve into larger wholes, even dialectically, about the tension of holding incompatible things together because both or all are necessary and true. Irony is about humour and serious play. It is also a rhetorical strategy and a political method, one I would like to see more honoured within socialist-feminism. At the centre of my ironic faith, my blasphemy, is the image of the cyborg. A cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction. Social reality is lived social relations, our most important political construction, a world-changing fiction. The international women's movements have constructed 'women's experience', as well as uncovered or discovered this crucial collective object. This experience is a fiction and fact of the most crucial, political kind. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Label: Artwork Location: Title: Review Locati

Bob Dylan Title: 04271992 Start Date: 04/27/1992 Location: Paramount Theater, Seattle, WA Label: Artwork Location: Review Location: Recording Source: Disc Number: 1 73:28 1 Rainy Day Women #12 & 35 01:24 2 I Don't Believe You 04:40 3 Union Sundown 04:23 4 Just Like A Woman 05:24 5 Tangled Up In Blue 08:23 6 She Belongs To Me 05:01 7 Everything's Broken 04:02 8 Love Minus Zero/No Limit 02:39 9 Little Moses 03:47 10 A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall 06:48 11 It;s All Over Now, Baby Blue 06:32 12 Cats In The Well 04:36 13 Idiot Wind 09:12 14 The Times They Are A-Changin' 06:37 Disc Number: 2 65:22 1 Highway 61 06:35 2 Absolutely Sweet Marie 05:38 3 All Along The Watchtower 04:20 cut 4 Blowin' In The Wind 03:25 start of 4/28 filler 5 Sally Sue Brown 02:56 6 Stuck Inside Of Mobile 06:35 7 Simple Twist Of Fate 07:40 8 Watching The River Flow 03:45 9 Female Rambling Sailor 03:04 10 Gates Of Eden 04:51 11 Shooting Star 05:24 12 Like A Rolling Stone 05:33 13 Ballad Of A Thin Man 05:36 Bob Dylan Title: 07011978 Start Date: 07/01/1978 Location: Zeppelindfeld, Nurnberg, West Germany Label: Artwork Location: http://www.angelfire.com/yt/tyamabe/nurnberg/ Review Location: Recording Source: Disc Number: 1 70:28 1 She's Love Crazy 02:30 2 Baby Stop Crying 05:39 3 Mr, Tambourine Man 04:28 4 Shelter From The Storm 04:51 5 It's All Over Now, Baby Blue 04:24 6 Tangled Up In Blue 07:07 7 Ballad Of A Thin Man 04:35 8 Maggie's Farm 04:47 9 I Don't Belive You 04:26 10 Like A Rolling Stone 06:39 11 I Shall Be Released 04:13 12 Going, Going, Gone 04:23 13 A Change Is -

The Mutual Influence of Science Fiction and Innovation

Nesta Working Paper No. 13/07 Better Made Up: The Mutual Influence of Science fiction and Innovation Caroline Bassett Ed Steinmueller George Voss Better Made Up: The Mutual Influence of Science fiction and Innovation Caroline Bassett Ed Steinmueller George Voss Reader in Digital Media, Professor of Information and Research Fellow, Faculty of Arts, Research Centre for Material Technology, SPRU, University University of Brighton, Visiting Digital Culture, School of of Communication Sussex Fellow at SPRU, University of Media, Film and Music, Sussex University of Sussex Nesta Working Paper 13/07 March 2013 www.nesta.org.uk/wp13-07 Abstract This report examines the relationship between SF and innovation, defined as one of mutual engagement and even co-constitution. It develops a framework for tracing the relationships between real world science and technology and innovation and science fiction/speculative fiction involving processes of transformation, central to which are questions of influence, persuasion, and desire. This is contrasted with the more commonplace assumption of direct linear transmission, SF providing the inventive seed for innovation– instances of which are the exception rather than the rule. The model of influence is developed through an investigation of the nature and evolution of genre, the various effects/appeals of different forms of expression, and the ways in which SF may be appropriated by its various audiences. This is undertaken (i) via an inter- disciplinary survey of work on SF, and a consideration the historical construction of genre and its on-going importance, (ii) through the development of a prototype database exploring transformational paths, and via more elaborated loops extracted from the database, and (iii) via experiments with the development of a web crawl tool, to understand at a different scale, using tools of digital humanities, how fictional ideas travel. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MARCH 9, 2020 | PAGE 1 OF 17 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Morris, Brown Top Charts Brandy Clark Makes A Personal >page 4 Statement On The Record Nashville Works Toward Recovery Ten seconds into Brandy Clark’s Your Life Is a Record, a the listener to an expectant conclusion of what turns out to be >page 9 languid grunting tone emerges, unconventionally planting a breakup album, released by Warner on March 6. “The Past a baritone sax into the opening moments of what’s ostensibly Is the Past,” she declares in that glassy finale, with fragile a country album. guitar arpeggios supporting a It’s a tad mysterious. In transitional journey into some Dan + Shay Launch context, it could be a bassoon or unknown future. Putting that Arena Tour a bass clarinet — Clark thought upbeat sentiment at the end >page 10 it was a cello the first time she of the project rather than the heard it — but it reveals to the beginning was one of the few listener that Your Life Is a Record, places where she dug in her heels produced by Jay Joyce (Eric with the label. Current News: Church, Miranda Lambert), “I wanted it that way because Just LeDoux It is not quite like either of the to me, ‘The Past Is the Past’ is >page 10 previous records the award- bittersweet, but it’s hopeful,” winning singer-songwriter has she explains. “It’s like, ‘OK, we’ve launched in the marketplace. gone through all this and I’m still Makin’ Tracks: “I said to Jay when I heard sad about it, but I’m letting you Pardi’s Strait Talk that baritone sax thing, ‘Man, go.’ And I’m driving away — like, >page 14 I know this is crazy ’cause it’s a I literally feel like I’m in the car slow, sad song.