Infants&Toddler Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copake Auction Inc. PO BOX H - 266 Route 7A Copake, NY 12516

Copake Auction Inc. PO BOX H - 266 Route 7A Copake, NY 12516 Phone: 518-329-1142 December 1, 2012 Pedaling History Bicycle Museum Auction 12/1/2012 LOT # LOT # 1 19th c. Pierce Poster Framed 6 Royal Doulton Pitcher and Tumbler 19th c. Pierce Poster Framed. Site, 81" x 41". English Doulton Lambeth Pitcher 161, and "Niagara Lith. Co. Buffalo, NY 1898". Superb Royal-Doulton tumbler 1957. Estimate: 75.00 - condition, probably the best known example. 125.00 Estimate: 3,000.00 - 5,000.00 7 League Shaft Drive Chainless Bicycle 2 46" Springfield Roadster High Wheel Safety Bicycle C. 1895 League, first commercial chainless, C. 1889 46" Springfield Roadster high wheel rideable, very rare, replaced headbadge, grips safety. Rare, serial #2054, restored, rideable. and spokes. Estimate: 3,200.00 - 3,700.00 Estimate: 4,500.00 - 5,000.00 8 Wood Brothers Boneshaker Bicycle 3 50" Victor High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle C. 1869 Wood Brothers boneshaker, 596 C. 1888 50" Victor "Junior" high wheel, serial Broadway, NYC, acorn pedals, good rideable, #119, restored, rideable. Estimate: 1,600.00 - 37" x 31" diameter wheels. Estimate: 3,000.00 - 1,800.00 4,000.00 4 46" Gormully & Jeffrey High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle 9 Elliott Hickory Hard Tire Safety Bicycle C. 1886 46" Gormully & Jeffrey High Wheel C. 1891 Elliott Hickory model B. Restored and "Challenge", older restoration, incorrect step. rideable, 32" x 26" diameter wheels. Estimate: Estimate: 1,700.00 - 1,900.00 2,800.00 - 3,300.00 4a Gormully & Jeffery High Wheel Safety Bicycle 10 Columbia High Wheel Ordinary Bicycle C. -

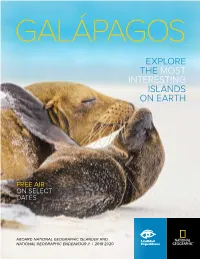

Explore the Most Interesting Islands on Earth

GALÁPAGOS EXPLORE THE MOST INTERESTING ISLANDS ON EARTH FREE AIR ON SELECT DATES ABOARD NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ISLANDER AND NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ENDEAVOUR II | 2018-2020 TM DEAR TRAVELER, Galápagos straddles the equator, is mercifully absent of hurricanes and cyclones, and fluctuates little weather-wise throughout the year. The animals are always there for us to observe up-close and personally. It is a geography that’s infinitely compelling, something you already know from countless magazine articles, nature programs, documentaries and more. But what you might not know is that it is the preeminent, guaranteed, slam-dunk vacation option for families. It offers something for everyone. And even better, it offers so much for families to share—it’s where meaningful memories get made together. Galápagos attracts, at least with us, a very diverse audience, driven largely by times when families travel and don’t. (See the chart at bottom right.) So, while Galápagos is always in season as far as wildlife and wonder are concerned, there are very distinct times to be there based on your preference in travel companions. If you don’t like the pitter patter of children’s feet, you can plan to visit when they’re absent. And if you are planning to explore as a family, and want other kids around, you can rely on the fact that we understand how to meet needs and create opportunities for kids of all ages. We’ve been at this for a very long time, ever since my father pioneered travel here in 1966. Galápagos is a very special place, and we are totally committed to ensuring that our guests get the most out of their time here. -

DECEMBER 6-19, 2018 ORWOODQ EWSQ Nvol

Proudly Serving Bronx Communities Since 1988 3URXGO\6HUYLQJ%URQ[&RPPXQLWLHV6LQFHFREE 3URXGO\6HUYLQJ%URQ[&RPPXQLWLHV6LQFHFREE ORWOODQ EWSQ NVol. 27, No. 8 PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION N April 17–30, 2014 Vol 31, No 24 • PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION • DECEMBER 6-19, 2018 ORWOODQ EWSQ NVol. 27, No. 8 PUBLISHED BY MOSHOLU PRESERVATION CORPORATION N April 17–30, 2014 FREE INQUIRING PHOTOGRAPHER: MTA: MOSHOLU PKWY. STATION CRIME CONCERNS | PG. 4 MAY GET ELEVATOR DOWN THE LINE | PG. 2 $3 MIL ROOF FIX FOR Hull Avenue Fire Victims Get Help pg 3 Pichardo securesBAILEY funding; hopes HOUSES to see repairs by next year In Norwood, a Mobile Library pg 8 Photo by David Cruz CB7 Rejects Bedford TIESHA JONES (AT MIC), Bailey Houses Residents Council president, speaks at a news conference announcing a $3 million allocation by Assemblyman Victor Pichardo (wearing beret) to x Bailey Houses’ roof. Park Buildings Plan pg 10 By JOSEPH KONIG “ T he roof i s ju st absolutely floor of the 20-story build- action to get it done hope- Assemblyman Victor in complete disrepair,” Pich- ing. And while the $3 mil- fully before the summer… Pichardo has earmarked $3 ardo, flanked by residents, lion in state funding should so when the next cold sea- million in capital funds for said at a news conference on help get the ball moving, the son comes around, the folks roof repairs at the Bailey Dec. 4. “This isn’t something timetable for repairs is still here at Bailey Houses have a Houses, a troubled NYCHA that’s abstract. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

January 2021 - Diy Plans Catalog

JANUARY 2021 - DIY PLANS CATALOG Anyone Can Do This! Our DIY Plans detail every aspect of the building process using easy to follow instructions with high resolution pictures and diagrams. Even if this is your first attempt at building something yourself, you will be able to succeed with our plans, as no previous expertise is assumed. Detailed Plans – Instant Download! We use real build photos and detailed diagrams instead of complex drawings, so anyone with a desire to build can succeed. Our bike and trike plans are not engineering blueprints, and do not call for hard-to-find parts or expensive tools. DIY Means Building Yourself a Better Life. Unleash your creativity, and turn your drawing board ideas into reality. You don't need a fancy garage full of tools or an unlimited budget to build anything shown on our DIY site, you just need the desire to do it yourself. Take pride in your home built projects, and create something completely unique from nothing more than recycled parts. AURORA DIY SUSPENSION TRIKE PLAN The Aurora Delta Recumbent Trike merges speed, handling, and comfort into one great looking ride! With under seat steering, and rear suspension, you will be enjoying your laid-back country cruises in pure comfort and style. Of course, The Aurora DIY Trike is also a hot performer, and will get you around as fast as your leg powered engine feels like working. This DIY Plan Contains 198 Pages and 203 Photos. Click above for more information. WARRIOR LOW RACER TADPOLE TRIKE PLAN The Warrior is one fast and great looking DIY Tadpole Trike that you can make using only basic tools and parts. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Dave\

Charlie Jr. Fails To Prove That He Is Not A Servant Of Stan Spring 2004 Issue 76 BHPC Newsletter - Issue 76 http://www.bhpc.org.uk/ Front Cover: Charlie Ollinger Jr. Photo: Jonathan Woolrich Back Cover: 2003 Unfaired champ Neil Fleming at the AGM Photo: Dave Larrington Contents Event Calendar 3 The Editor’s Bit 7 Racing News 9 More Battle Mountain Jonathan Woolrich / Bill Cook / Larry Lem 15 Suppliers And Wants 26 Objectives: The British Human Power Club was formed to foster all aspects of human-powered vehicles - air, land & water - for competitive, recreational and utility activities, to stimulate innovation in design and development in all spheres of HPV's, and to promote and to advertise the use of HPV's in a wide range of activities. Trout, when heated correctly, make perfect under arm warmers. OFFICERS Chairman & Press Officer Membership & Distribution Richard Ballantine Dennis Turner 30 Oppidans Road 7 West Bank, London NW3 3AG Abbot's Park ( 020 7722 6918 Chester, CH1 4BD e-mail: [email protected] ( Home 01244 376665 Competition Secretary e-mail: [email protected] gNick Green Librarian 79, Front Street, Pete Cox Pity Me, Belmont Cottage Durham, DH1 5DE Church Road ( Mobile 07971 519811 Saughall e-mail: [email protected] Chester, CH1 6EP Treasurer ( Home 01244 880574 Fiona Grove e-mail: [email protected] 7 Salmon Close Newsletter Mangler Bloxham, Banbury, Dave Larrington Oxon, OX15 4PJ 166 Higham Hill Road ( Home 01295 721860 London E17 6EJ e-mail: [email protected] ( Home 0208 531 4496 Secretary (after 19:00 weekdays Anne Tweddle please...) 1 Chipperfield Park Road e-mail: [email protected] Bloxham, Banbury or: [email protected] Oxon, OX15 4NX ( Home 01295 720615 e-mail: [email protected] Issue 77 closes June 1st 2004 Letters, articles, pictures, gainful employment, etc. -

Cyclist GO the DISTANCE

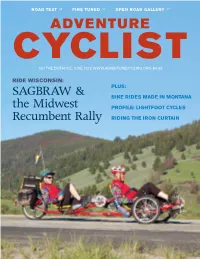

ROAD TEST 36 FINE TUNED 40 OPEN ROAD GALLERY 47 ADVENTURE CYCLIST GO THE DISTANCE. JUne 2012 WWW.ADVentURecYCLing.ORG $4.95 RIDE WISCONSIN: PLUS: SAGBRAW & BIKE RIDES MADE IN MONTANA the Midwest PROFILE: LIGHTFOOT CYCLES Recumbent Rally RIDING THE IRON CURTAIN Share the Joy GET A CHANCE TO WIN 6:2012 contents Spread the joy of cycling and get a chance to win cool prizes June 2012 · Volume 39 Number 5 · www.adventurecycling.org n For each cyclist you refer to Adventure Cycling, you will ADVENTURE get one chance to win a Giant Rapid 1* valued at over $1,250. The winner will be drawn from all eligible CYCLIST members in January of 2013. is published nine times each year by the Adventure Cycling Association, n Each month, we’ll draw a mini-prize winner who a nonprofit service organization for recreational bicyclists. Individual will receive gifts from Old Man Mountain, Arkel, membership costs $40 yearly to U.S. Ortlieb, and others. addresses and includes a subscrip- tion to Adventure Cyclist and dis- n The more new members you sign up, the more counts on Adventure Cycling maps. chances you have to win! The entire contents of Adventure Cyclist are copyrighted by Adventure Cyclist and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written * Bicycle model may change with release of new or updated models. permission from Adventure Cyclist. All rights reserved. Adventure Cycling Association adventurecycling.org/joy OUR COVER Cycle Montana riders clip along on their recumbent tandem trike. Photo by Greg Siple. Y (left) A cyclist winds through the HANE forest on the Whitefish Trail in Adventure Cycling Corporate Members K C U Montana. -

20Th Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction

CATALOG PRICE $4.00 Michael E. Fallon Seth E. Fallon COPAKE AUCTION INC. 266 Rt. 7A - Box H, Copake, N.Y. 12516 PHONE (518) 329-1142 FAX (518) 329-3369 Email: [email protected] Website: www.copakeauction.com 20th Annual Antique & Classic Bicycle Auction ************************************ Auction: Saturday April 16, 2011 at 10 am Swap Meet: Friday April 15th Dawn ‘til Dusk Always Accepting Quality Consignments – Contact Us! TERMS: Everything sold “as is”. No condition reports in descriptions. Bidder must look over every lot to determine condition and authenticity. Cash or Travelers Checks Mastercard, Visa and Discover Accepted First time buyers cannot pay by check without a bank letter of credit 15% BUYERS PREMIUM (2% discount for payment of cash or check) National Auctioneers Association - NYS Auctioneers Association CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Some of the lots in this sale are offered subject to a reserve. This reserve is a confidential minimum price agreed upon by the consignor & COPAKE AUCTION below which the lot will not be sold. In any event when a lot is subject to a reserve, the auctioneer may reject any bid not adequate to the value of the lot. 2. All items are sold "as is" and neither the auctioneer nor the consignor makes any warranties or representations of any kind with respect to the items, and in no event shall they be responsible for the correctness of the catalogue or other description of the physical condition, size, quality, rarity, importance, medium, provenance, period, source, origin or historical relevance of the items and no statement anywhere, whether oral or written, shall be deemed such a warranty or representation. -

Bicycles (As Shown in Free Youth and Family Movement

RIDING HIGH\MTH REPCO 69cmwheels SUPERLITE CHROME MOLY 12 SPEED Equipped with: 730 c hrome moly frame, alloy Dia Compe side pull bra kes with safety levers, a lloy stem, alloy ha ndlebar with c loth tape, brazed on cable stoppers, racing c hime bell, Sugino cotterless aero a lloy cranks, nickelplated chain, racing padded saddle, Suntour Seven 12 speed gears, Italian Nisi alloy wheels with front quick release hub, gumwall tyres, steel reflector pedals, safety reflectors. Colours: Beige with Dark Brown, Sky Blue with Dark Blue. Available in two frame sizes: Model 2781/12Rframe size 53cm Model 2783/12R frame size 58cm. 69cmwheels LE MANS 12 SPEED Equipped with: 755 Hi Tensile frame, Alloy Dia Compe brakes with safety levers, a ll oy stem, handlebar with c loth tape, brazed on cable stopper, racing chime bell, Sugino cotterless Aero a lloy cranks, vinyl racing saddle, Suntour 12 speed a lloy gears, a ll oy stand, q uick release front hub, gumwall tyres, steel reflector pedals, safety reflectors. Colours: Burgundy Red, Midnight Blue, Sable Black. Available in three different frame sizes: Model 2765/12R 53cm fra me size Model 2760/1 2R 58cm frame size Model 2770/1 2R 63cm frame size. REPCO Available from all leading Cycle Dealers. NUMBER SEVENTEEN TWO DOLLARS NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 1982 CONTENTS 4 Freewheeling Readers and Dealers Classifieds National Bike Events Calendar 5 Between the Lines News from Freewheeling 6 New Products and Ideas Some interesting gift ideas for Christmas 14 Cyclistes Those amazing women of the Victorian era. 22 Touring with -

NYCC May 2003 Sing.Qrk

June Roster is being produced NOW! Please CHECK YOUR INFORMATION with the December roster and notify the MEMBERSHIP Coordinator of changes. Bulletin NEW YORK CYCLE CLUB New Club Jersey Designer/Richard Rosenthal A NOTE ON THE DESIGN OF sey used the one that is most all those things: function as the cables.) the Statue of Liberty. So pause and think for a Look at the curvilear shape and step-back of YOUR NEW CLUB JERSEY moment: what are the ones you think of next? the top of the Chrysler Building and observe If you were designing a jersey for, say, the My new design makes use of two of them how the decorative, spike-like triangles radiate, Muskegon, Michigan cycle club, you might be (and possibly a remembrance of a third): it further implying the arc the suggestion of the obliged to create a generic jersey—one that is observes a similarity of appearance between domes do. Now look at your cogset. With a bit like thousands of others, merely consisting of those landmarks and parts of your of imagination, doesn't one suggest the stripes, bands, blotches, and blocs of color. bicycle...because the jersey should say "bicy- appearance of the other to you? They do to But New York is like no other city and a jer- cle" in picture as well as word, just as much as me. sey for our cycle club should be like no other: it should say "New York." If I may say so myself, your new club jersey, it should use the symbols and imagery of this Look at the radiating cables on the Brooklyn we hope available in mid-summer, says and city; it should be particular to New York; it Bridge. -

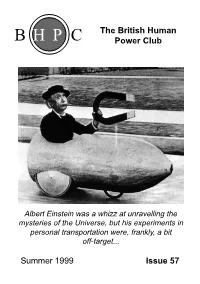

Issue 57 BHPC Newsletter - Issue 57

The British Human B H P C Power Club Albert Einstein was a whizz at unravelling the mysteries of the Universe, but his experiments in personal transportation were, frankly, a bit off-target... Summer 1999 Issue 57 BHPC Newsletter - Issue 57 Front Cover: Oi! Einstein!! NO!!! A postcard discovered by Tina in Hamburg Back Cover: Based on characters painted by some Italian geezer. Michelangelo? Mario Cipollini? I dunno... Contents Racing Events gNick, mainly 3 Touring and Socialising Events Various 3 The Six O’Clock News Dave Larrington 5 The Epistles You, Constant Reader 10 Builder’s Corner Geoff Bird, Michael Allen, Rick Valbuena, Me 12 History Lesson 1 Richard Middleton 23 History Lesson 2 Nick Bigg 25 Racing News Dave Larrington 26 Stop Press!!! Various 38 A Word From Our Sponsor Treasurer Dennis Adcock 39 Suppliers & Wants 41 Adam and Joe Tina Larrington 48 Objectives: The British Human Power Club was formed to foster all aspects of human-powered vehicles - air, land & water - for competitive, recreational and utility activities, to stimulate innovation in design and development in all spheres of HPV's, and to promote and to advertise the use of HPV's in a wide range of activities. I don’t want to drink my whisky like you do. OFFICERS Chairman & Press Officer Dave Cormie ( Home 0131 552 3148 143 East Trinity Road Edinburgh, EH5 3PP Competition Secretary gNick Green ( Home 01785 223576 267 Tixall Road Stafford, ST16 3XS E-mail: [email protected] Secretary Steve Donaldson ( Home 01224 772164 Touring Secretary Sherri Donaldson 15 Station -

Bicycle Design

BICYCLE DESIGN BICYCLE DESIGN An Illustrated History TONY HADLAND AND HANS-ERHARD LESSING with contributions from Nick Clayton and Gary W. Sanderson The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, email [email protected]. Set in Helvetica Neue by The MIT Press. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hadland, Tony. Bicycle design : an illustrated history / Tony Hadland and Hans-Erhard Lessing; with contributions from Nick Clayton and Gary W. Sanderson. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-02675-8 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Bicycles—Design and construction—History. 2. Bicycles— Parts—History. I. Lessing, Hans-Erhard. II. Title. TL400.H33 2014 629.2’31—dc23 2013023698 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 I’M MORE INTERESTED IN A WORLD THAT WORKS THAN WHAT SELLS. Paul MacCready, pioneer of human-powered flight CONTENTS Preface xi Acknowledgments xv A Note on Spelling and on the Names of Components xvii 1 Velocipedes and Their Forerunners 1 Mobility before the velocipede 1 A shortage of oats necessitates horseless transport 8 Diffusion of the single-track