Special Issue: Early Career Researchers I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance U.S

1 Check website or mobile app for full description and content information. description app for full Check website or mobile #sundance • sundance.org/festival sundance.org/festival Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance The U.S. Dramatic Competition Films As You Are The Birth of a Nation U.S. Dramatic Competition Dramatic U.S. Many of these films have not yet been rated by the Motion Picture Association of America. Read the full descriptions online and choose responsibly. Films are generally followed by a Q&A with the director and selected members of the cast and crew. All films are shown in 35mm, DCP, or HDCAM. Special thanks to Dolby Laboratories, Inc., for its support of our U.S.A., 2016, 110 min., color U.S.A., 2016, 117 min., color digital cinema projection. As You Are is a telling and retelling of a Set against the antebellum South, this story relationship between three teenagers as it follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and traces the course of their friendship through preacher whose financially strained owner, PROGRAMMERS a construction of disparate memories Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use prompted by a police investigation. Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. Director, Associate Programmers Sundance Film Festival Lauren Cioffi, Adam Montgomery, After witnessing countless atrocities against 2 John Cooper Harry Vaughn fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his DIRECTOR: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte people to freedom. Director of Programming Shorts Programmers SCREENWRITERS: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Trevor Groth Dilcia Barrera, Emily Doe, Madison Harrison Ernesto Foronda, Jon Korn, PRINCIPAL CAST: Owen Campbell, DIRECTOR/SCREENWRITER: Nate Parker Senior Programmers Katie Metcalfe, Lisa Ogdie, Charlie Heaton, Amandla Stenberg, PRINCIPAL CAST: Nate Parker, David Courier, Shari Frilot, Adam Piron, Mike Plante, Kim Yutani, John Scurti, Scott Cohen, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Caroline Libresco, John Nein, Landon Zakheim Mary Stuart Masterson Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mike Plante, Charlie Reff, Kim Yutani Mark Boone Jr. -

State Funding Oods Into Swampscott

TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2020 N.H. Improved credit rating saves Lynn $753,903 By Gayla Cawley “With S&P Global Ratings changing the “We did it to lower the city’s obligations,” up for ITEM STAFF city’s outlook from neutral to positive, we said Bertino. “Whenever you refund bonds, it have been able to secure competitive bids that has to be in the city’s best interest. It has to LYNN — An improved credit rating outlook will save the city $753,903 over the life of the save the city a certain amount of money. We has allowed the city to re nance its bonds, bonds,” said McGee in a statement. “The bond replaced bonds (and) got a much better deal grabs which will result in a $753,903 savings over rating agencies are recognizing the results of on the new ones.” the 15-year borrowing period, according to the progress we have made working together City Council President Darren Cyr said he Chief Financial Of cer Michael Bertino. over the last two years.” was pleased with the savings achieved with today The city received ve competitive bids from Borrowing at a 1.3 percent interest rate is the re nancing. bond underwriters on Jan. 22 for a $7.58 mil- “very favorable,” said Bertino, who added the “I am hopeful that the city can now begin ROCHESTER, N.H. lion, 15-year general obligation state quali- bond proceeds will allow the city to re nance to move forward to replace its aging school (AP) — In the waning ed bond issue. -

Getting to “The Pointe”

Running head: GETTING TO “THE POINTE” GETTING TO “THE POINTE”: ASSESSING THE LIGHT AND DARK DIMENSIONS OF LEADERSHIP ATTRIBUTES IN BALLET CULTURE Ashley Lauren Whitely B.A., Western Kentucky University, 2003 M.A., Western Kentucky University, 2006 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty under the supervision of Gail F. Latta, Ph.D. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Leadership Studies Xavier University Cincinnati, OH May 2017 Running head: GETTING TO “THE POINTE” Running head: GETTING TO “THE POINTE” GETTING TO “THE POINTE”: ASSESSING THE LIGHT AND DARK DIMENSIONS OF LEADESHIP ATTRIBUTES IN BALLET CULTURE Ashley Lauren Whitely Dissertation Advisor: Gail F. Latta, Ph.D. Abstract The focus of this ethnographic study is to examine the industry-wide culture of the American ballet. Two additional research questions guided the investigation: what attributes, and their light and dark dimensions, are valued among individuals selected for leadership roles within the culture, and how does the ballet industry nurture these attributes? An understanding of the culture was garnered through observations and interviews conducted in three classically-based professional ballet companies in the United States: one located in the Rocky Mountain region, one in the Midwestern region, and one in the Pacific Northwest region. Data analysis brought forth cultural and leadership themes revealing an industry consumed by “the ideal” to the point that members are willing to make sacrifices, both at the individual and organizational levels, for the pursuit of beauty. The ballet culture was found to expect its leaders to manifest the light dimensions of attributes valued by the culture, because these individuals are elevated to the extent that they “become the culture,” but they also allow these individuals to simultaneously exemplify the dark dimensions of these attributes. -

Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance U.S

1 #sundance • sundance.org/festival sundance.org/festival Sundance Institute Presents Institute Sundance Check website or mobile app for full description and content information. The U.S. Dramatic Competition Films As You Are The Birth of a Nation U.S. Dramatic Competition Dramatic U.S. Many of these films have not yet been rated by the Motion Picture Association of America. Read the full descriptions online and choose responsibly. Films are generally followed by a Q&A with the director and selected members of the cast and crew. All films are shown in 35mm, DCP, or HDCAM. Special thanks to Dolby Laboratories, Inc., for its support of our U.S.A., 2016, 110 min., color U.S.A., 2016, 110 min., color digital cinema projection. As You Are is a telling and retelling of a Set against the antebellum South, this story relationship between three teenagers as it follows Nat Turner, a literate slave and traces the course of their friendship through preacher whose financially strained owner, PROGRAMMERS a construction of disparate memories Samuel Turner, accepts an offer to use prompted by a police investigation. Nat’s preaching to subdue unruly slaves. Director, Associate Programmers Sundance Film Festival Lauren Cioffi, Adam Montgomery, After witnessing countless atrocities against 2 John Cooper Harry Vaughn fellow slaves, Nat devises a plan to lead his DIRECTOR: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte people to freedom. Director of Programming Shorts Programmers SCREENWRITERS: Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, Trevor Groth Dilcia Barrera, Emily Doe, Madison Harrison Ernesto Foronda, Jon Korn, PRINCIPAL CAST: Owen Campbell, DIRECTOR/SCREENWRITER: Nate Parker Senior Programmers Katie Metcalfe, Lisa Ogdie, Charlie Heaton, Amandla Stenberg, PRINCIPAL CAST: Nate Parker, David Courier, Shari Frilot, Adam Piron, Mike Plante, Kim Yutani, John Scurti, Scott Cohen, Armie Hammer, Aja Naomi King, Caroline Libresco, John Nein, Landon Zakheim Mary Stuart Masterson Jackie Earle Haley, Gabrielle Union, Mike Plante, Charlie Reff, Kim Yutani Mark Boone Jr. -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

Social Justice Practices for Educational Theatre

VOLUME 7 ISSUE 2b | 2020 SOCIAL JUSTICE PRACTICES FOR EDUCATIONAL THEATRE ARTSPRAXIS Emphasizing critical analysis of the arts in society. ISSN: 1552-5236 EDITOR Jonathan P. Jones, New York University, USA EDITORIAL BOARD Selina Busby, The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, UK Amy Cordileone, New York University, USA Ashley Hamilton, University of Denver, USA Norifumi Hida, Toho Gakuen College of Drama and Music, Japan Kelly Freebody, The University of Sydney, Australia Byoung-joo Kim, Seoul National University of Education, South Korea David Montgomery, New York University, USA Ross Prior, University of Wolverhampton, UK Daphnie Sicre, Loyola Marymount University, USA James Webb, Bronx Community College, USA Gustave Weltsek, Indiana University Bloomington, USA Tammie Swopes, New York University, USA ArtsPraxis Volume 7, Issue 2b looked to engage members of the global Educational Theatre community in dialogue around current research and practice. This call for papers was released in concert with the publication of ArtsPraxis Volume 7, Issue 1 and upon the launch of the new ArtsPraxis homepage. The submission deadline for Volume 7, Issue 2b was July 15, 2020. Submissions fell under the category of Social Justice Practices for Educational Theatre. Social Justice Practices for Educational Theatre As of early June, 2020, we found ourselves about ten days into international protests following the murder of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Protesters the world over made specific calls to action: acknowledge that black lives matter, educate yourself about social and racial injustice, and change the legal system that allows these heinous acts to go unpunished. In thinking through how we in the field of educational theatre could proactively address these needs, I reminded myself that there were many artists and educators who were already deeply engaged in this work. -

Cablefax Dailytm Cablefax Dailytm

www.cablefax.com, Published by Access Intelligence, LLC, Tel: 301-354-2101 4 Pages Today CableFAX DailyTM Monday — August 26, 2013 What the Industry Reads First Volume 24 / No. 165 Summer Time: Cable Continues to Chip Away at Broadcast Cable’s usually sizzles in the summer, and with only a few days remaining, it looks like this year was no exception. Household share for ad-supported cable was up more than 5 points from a year ago and more than 3x the combined 4 broadcast nets’ share, which was down 5 points from ’12, according to a Turner analysis of summer-to-date data from Nielsen. Turner projects cable’s share at 76%. Ad-supported cable’s share among 18-49s is projected to hit a record high of 78%, up 6 percentage points from a year ago. Online video doesn’t seem to be having much of an impact at this point, with viewing of ad-supported cable at an all-time high and average hours of viewing per person per week at 17.4, up from 17 last year, Turner said. The broadcast nets’ average viewing per person slipped to 6.2 hours from 6.8 last year. USA continues its reign, with the net easily expected to nab its 8th consecutive summer win among total viewers (2.91mln) 18-49s (1.07mln) and 25-54s (1.13mln) in prime. There’s a new champ in the 18-34 category, with Adult Swim celebrating its first #1 summer finish among the demo in prime. Compared to the same period last year, the net’s average primetime delivery for 18-34s swelled 19% to 555K. -

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Vol1.Pdf

Writing Figures of Political Resistance for the British Stage Volume One (of Two) Matthew John Midgley PhD University of York Theatre, Film and Television September 2015 Writing Figures of Resistance for the British Stage Abstract This thesis explores the process of writing figures of political resistance for the British stage prior to and during the neoliberal era (1980 to the present). The work of established political playwrights is examined in relation to the socio-political context in which it was produced, providing insights into the challenges playwrights have faced in creating characters who effectively resist the status quo. These challenges are contextualised by Britain’s imperial history and the UK’s ongoing participation in newer forms of imperialism, the pressures of neoliberalism on the arts, and widespread political disengagement. These insights inform reflexive analysis of my own playwriting. Chapter One provides an account of the changing strategies and dramaturgy of oppositional playwriting from 1956 to the present, considering the strengths of different approaches to creating figures of political resistance and my response to them. Three models of resistance are considered in Chapter Two: that of the individual, the collective, and documentary resistance. Each model provides a framework through which to analyse figures of resistance in plays and evaluate the strategies of established playwrights in negotiating creative challenges. These models are developed through subsequent chapters focussed upon the subjects tackled in my plays. Chapter Three looks at climate change and plays responding to it in reflecting upon my creative process in The Ends. Chapter Four explores resistance to the Iraq War, my own military experience and the challenge of writing autobiographically. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Current feminist theatre scholarship tends to use the term ‘heteronormative’. The predominant use of the term ‘heterosexist’ in this study draws directly from black lesbian feminist Audre Lorde’s notion of ‘Heterosexism [as] the belief in the inherent superiority of one pattern of loving and thereby its right to dominance’ (Lorde, 1984, p. 45). 2. See Diana Fuss, Essentially Speaking: Feminism, Nature and Difference (London: Routledge, 1989) for summaries and discussions of the essen- tialism/constructionism debates. 3. See, for example, Elaine Aston, An Introduction to Feminism and Theatre (London: Routledge, 1995); Elaine Aston, Feminist Views on the English Stage: Women Playwrights, 1990–2000 (Cambridge: CUP, 2003); Mary F. Brewer, Race, Sex and Gender in Contemporary Women’s Theatre: The Construction of ‘Woman’ (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 1999); Lizbeth Goodman, Contemporary Feminist Theatres: To Each Her Own (London: Routledge, 1993); and Gabriele Griffin Contemporary Black and Asian Women Playwrights in Britain (Cambridge: CUP, 2003). 4. See, for example, Susan Croft, ‘Black Women Playwrights in Britain’ in Trevor R. Griffiths and Margaret Llewellyn Jones, eds, British and Irish Women Dram- atists Since 1968 (Buckingham: OUP, 1993); Mary Karen Dahl, ‘Postcolonial British Theatre: Black Voices at the Center’ in J. Ellen Gainor, ed., Imperi- alism and Theatre: Essays on World Theatre, Drama and Performance (London: Routledge, 1995); Sandra Freeman, Putting Your Daughters on the Stage: Lesbian Theatre from -

Report by % of Episodes Directed by Women

2013 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by % of EPISODES DIRECTED BY WOMEN) Title Total # of # Episodes Female # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Signatory Company Network Episodes Directed by % Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Females Male % Male % Female % Female % Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A.N.T. Farm 39 0 0% 30 77% 9 23% 0 0% 0 0% It's a Laugh Productions, Inc. Disney Channel After Lately 8 0 0% 8 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% CP Entertainment Services, LLC E! American Horror Story 13 0 0% 10 77% 3 23% 0 0% 0 0% Twentieth Century Fox Television FX Anger Management 54 0 0% 53 98% 1 2% 0 0% 0 0% Anger Productions, Inc. FX Californication 12 0 0% 11 92% 1 8% 0 0% 0 0% Showtime Pictures Development Showtime Company Crash and Bernstein 26 0 0% 24 92% 2 8% 0 0% 0 0% It's a Laugh Productions, Inc. Disney XD Defiance 11 0 0% 9 82% 2 18% 0 0% 0 0% Open 4 Business Productions LLC Syfy Dog with a Blog 21 0 0% 20 95% 1 5% 0 0% 0 0% It's a Laugh Productions, Inc. Disney Channel Exes, The 12 0 0% 12 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% King Street Productions Inc. TV Land Falling Skies 10 0 0% 10 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Turner North Center Productions, Inc. TNT Fringe 13 0 0% 12 92% 1 8% 0 0% 0 0% Warner Bros. -

1-0 Website Approved Projects List Online 12-11-17

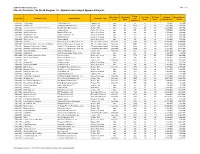

California Film Commission Page 1 of 7 Film and Television Tax Credit Program 1.0 - Alphabetical Listing of Approved Projects Extras Non-Indie or CA Filming # of Crew # of Cast Qualified Reservation of Fiscal Year Production Title Company Name Production Type and Indie Days Hired Hired Expenditures Credits Stand-ins 2010/2011 10,000 Days 10,000 Days, LLC Feature Film Indie 15 74 77 17 993,000 248,000 2010/2011 A Better Life Jardinero Productions, LLC Feature Film Indie 40 3414 147 68 7,074,000 1,768,000 2011/2012 A Glimpse Inside the Mind of Charles Swan III The Director's Bureau, LLC Feature Film Indie 21 140 40 39 2,285,000 571,000 2013/2014 A Lesson in Love Leipzig Limited Movie of the Week Indie 24 275 65 36 1,759,000 440,000 2015/2016 A Moving Romance Biggsville Films, Inc. Movie of the Week Indie 20 200 60 14 1,543,000 386,000 2010/2011 Accidently in Love Carlito Productions, Inc. Movie of the Week Indie 24 246 71 34 1,560,000 390,000 2015/2016 Advance and Retreat Marsberg limited Movie of the Week Indie 20 250 60 23 1,543,000 386,000 2009/2010 After The Fall Robigo Limited Movie of the Week Indie 24 162 62 28 1,460,000 365,000 2015/2016 Agent X 1 Turner North Center Productions, Inc. TV series (Basic Cable) Non-Indie 72 1370 300 80 26,499,000 5,300,000 2015/2016 American Crime Story 1: The People v. -

2015 Pilot Production Report

Each year between January and April, Los Angeles residents observe a marked increase in local on-location filming. New television pilots, produced in anticipation of May screenings for television advertisers, join continuing TV series, feature films and commercial projects in competition for talent, crews, stage 6255 W. Sunset Blvd. CREDITS: space and sought-after locations. 12th Floor Research Analysts: Hollywood, CA 90028 Adrian McDonald However, Los Angeles isn’t the only place in North America Corina Sandru hosting pilot production. Other jurisdictions, most notably New Graphic Design: York and the Canadian city of Vancouver have established http://www.filmla.com/ Shane Hirschman themselves as strong competitors for this lucrative part of @FilmLA Hollywood’s business tradition. Below these top competitors is FilmLA Photography: a second-tier of somewhat smaller players in Georgia, Louisiana Shutterstock and Ontario, Canada— home to Toronto. FilmL.A.’s official count shows that 202 broadcast, cable and digital pilots (111 Dramas, 91 Comedies) were produced during the 2014-15 development cycle, one less than the prior year, TABLE OF CONTENTS which was the most productive on record by a large margin. Out of those 202 pilots, a total of 91 projects (21 Dramas, 70 WHAT’S A PILOT? 3 Comedies) were filmed in the Los Angeles region. NETWORK, CABLE, AND DIGITAL 4 FilmL.A. defines a development cycle as the period leading up to GROWTH OF DIGITAL PILOTS 4 the earliest possible date that new pilots would air, post-pickup. DRAMA PILOTS 5 Thus, the 2013-14 development cycle includes production COMEDY PILOTS 5 activity that starts in 2013 and continues into 2014 for show THE MAINSTREAMING OF “STRAIGHT-TO-SERIES” PRODUCTION 6 starts at any time in 2014 (or later).