Life of John Eliot: the Apostle to the Indians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Decline of Algonquian Tongues and the Challenge of Indian Identity in Southern New England

Losing the Language: The Decline of Algonquian Tongues and the Challenge of Indian Identity in Southern New England DA YID J. SIL VERMAN Princeton University In the late nineteenth century, a botanist named Edward S. Burgess visited the Indian community of Gay Head, Martha's Vineyard to interview native elders about their memories and thus "to preserve such traditions in relation to their locality." Among many colorful stories he recorded, several were about august Indians who on rare, long -since passed occasions would whisper to one another in the Massachusett language, a tongue that younger people could not interpret. Most poignant were accounts about the last minister to use Massachusett in the Gay Head Baptist Church. "While he went on preaching in Indian," Burgess was told, "there were but few of them could know what he meant. Sometimes he would preach in English. Then if he wanted to say something that was not for all to hear, he would talk to them very solemnly in the Indian tongue, and they would cry and he would cry." That so few understood what the minister said was reason enough for the tears. "He was asked why he preached in the Indian language, and he replied: 'Why to keep up my nation.' " 1 Clearly New England natives felt the decline of their ancestral lan guages intensely, and yet Burgess never asked how they became solely English speakers. Nor have modem scholars addressed this problem at any length. Nevertheless, investigating the process and impact of Algonquian language loss is essential for a fuller understanding Indian life during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and even beyond. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

Essay by Julian Pooley; University of Leicester, John Nichols and His

'A Copious Collection of Newspapers' John Nichols and his Collection of Newspapers, Pamphlets and News Sheets, 1760–1865 Julian Pooley, University of Leicester Introduction John Nichols (1745–1826) was a leading London printer who inherited the business of his former master and partner, William Bowyer the Younger, in 1777, and rose to be Master of the Stationers’ Company in 1804.1 He was also a prominent literary biographer and antiquary whose publications, including biographies of Hogarth and Swift, and a county history of Leicestershire, continue to inform and inspire scholarship today.2 Much of his research drew upon his vast collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century newspapers. This essay, based on my ongoing work on the surviving papers of the Nichols family, will trace the history of John Nichols’ newspaper collection. It will show how he acquired his newspapers, explore their influence upon his research and discuss the changing fortunes of his collection prior to its acquisition by the Bodleian Library in 1865. 1 For useful biographical studies of John Nichols, see Albert H. Smith, ‘John Nichols, Printer and 2 The first edition of John Nichols’ Anecdotes of Mr Hogarth (London, 1780) grew, with the assistance Publisher’ The Library Fifth Series 18.3 (September 1963), pp. 169–190; James M. Kuist, The Works of Isaac Reed and George Steevens, into The Works of William Hogarth from the Original Plates of John Nichols. An Introduction (New York, 1968), Alan Broadfield, ‘John Nichols as Historian restored by James Heath RA to which is prefixed a biographical essay on the genius and productions of and Friend. -

The Narragansett Planters 49

1933.] The Narragansett Planters 49 THE NARRAGANSETT PLANTERS BY WILLIAM DAVIS MILLER HE history and the tradition of the "Narra- T gansett Planters," that unusual group of stock and dairy farmers of southern Rhode Island, lie scattered throughout the documents and records of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and in the subse- quent state and county histories and in family genealo- gies, the brevity and inadequacy of the first being supplemented by the glowing details of the latter, in which imaginative effort and the exaggerative pride of family, it is to be feared, often guided the hand of the chronicler. Edward Channing may be considered as the only historian to have made a separate study of this community, and it is unfortunate that his monograph. The Narragansett Planters,^ A Study in Causes, can be accepted as but an introduction to the subject. It is interesting to note that Channing, believing as had so many others, that the unusual social and economic life of the Planters had been lived more in the minds of their descendants than in reality, intended by his monograph to expose the supposed myth and to demolish the fact that they had "existed in any real sense. "^ Although he came to scoff, he remained to acknowledge their existence, and to concede, albeit with certain reservations, that the * * Narragansett Society was unlike that of the rest of New England." 'Piiblinhed as Number Three of the Fourth Scries in the John» Hopkini Umtertitj/ Studies 111 Hittirieal and Political Science, Baltimore, 1886. "' l-Mward Channing^—came to me annoiincinn that he intended to demolish the fiction thiit they I'xistecl in any real Bense or that the Btnte uf society in soiithpni Rhode Inland iliiTcrpd much from that in other parts of New EnRland. -

Colonial America Saturdays, August 22 – October 10 9:30 AM to 12:45 PM EST

Master of Arts in American History and Government Ashland University AHG 603 01A Colonial America Saturdays, August 22 – October 10 9:30 AM to 12:45 PM EST Sarah Morgan Smith and David Tucker Course focus: This course focuses on the development of an indigenous political culture in the British colonies. It pays special attention to the role of religion in shaping the American experience and identity of ‘New World’ inhabitants, as well as to the development of representative political institutions and how these emerged through the confrontation between colonists and King and proprietors. Learning Objectives: To increase participants' familiarity with and understanding of: 1. The reasons for European colonization of North America and some of the religious and political ideas that the colonists brought with them, as well as the ways those ideas developed over the course of the 17th-18th centuries 2. The “first contact” between native peoples and newcomers emphasizing the world views of Indians and Europeans and the way each attempted to understand the other. 3. The development of colonial economies as part of the Atlantic World, including servitude and slavery and the rise of consumerism. 4. Religion and intellectual life and the rise of an “American” identity. Course Requirements: Attendance at all class sessions. Presentation/Short Paper: 20% o Each student will be responsible for helping to guide our discussion during one session of the courses by making a short presentation to the class and developing additional focus/discussion questions related to the readings (beyond those listed in the syllabus). On the date of their presentation, the student will also submit a three page paper and a list of (additional) discussion questions. -

Pdf\Preparatory\Charles Wesley Book Catalogue Pub.Wpd

Proceedings of the Charles Wesley Society 14 (2010): 73–103. (This .pdf version reproduces pagination of printed form) Charles Wesley’s Personal Library, ca. 1765 Randy L. Maddox John Wesley made a regular practice of recording in his diary the books that he was reading, which has been a significant resource for scholars in considering influences on his thought.1 If Charles Wesley kept such diary records, they have been lost to us. However, he provides another resource among his surviving manuscript materials that helps significantly in this regard. On at least four occasions Charles compiled manuscript catalogues of books that he owned, providing a fairly complete sense of his personal library around the year 1765. Indeed, these lists give us better records for Charles Wesley’s personal library than we have for the library of brother John.2 The earliest of Charles Wesley’s catalogues is found in MS Richmond Tracts.3 While this list is undated, several of the manuscript hymns that Wesley included in the volume focus on 1746, providing a likely time that he started compiling the list. Changes in the color of ink and size of pen make clear that this was a “growing” list, with additions being made into the early 1750s. The other three catalogues are grouped together in an untitled manuscript notebook containing an assortment of financial records and other materials related to Charles Wesley and his family.4 The first of these three lists is titled “Catalogue of Books, 1 Jan 1757.”5 Like the earlier list, this date indicates when the initial entries were made; both the publication date of some books on the list and Wesley’s inscriptions in surviving volumes make clear that he continued to add to the list over the next few years. -

1152 Eblj Article 9 2005

Early Eastern Algonquian Language Books in the British Library Early Eastern Algonquian Language Books in the British Library Adrian S. Edwards Dispersed across the early printed book collections of the British Library, there are many important works relevant to the study of the indigenous languages of North America. This article considers materials in or about the Eastern Algonquian group of languages. These include the languages of New England first encountered by Puritan settlers from Britain in the mid-seventeenth century. The aim is to survey what can be found in the Library, and to place these items in a linguistic and historical context. Any survey has to have its limits, and this study considers only volumes printed before the middle of the nineteenth century. This limit means that the first examples of printing in each of the published Eastern Algonquian languages are included; it also reflects the pragmatic view taken in the British Library reading rooms that ‘early’ means before the mid-nineteenth century. The study includes all letterpress books and pamphlets, irrespective of whether they were issued in Europe or North America. ‘A’ reference numbers in square brackets, e.g. [A1], relate to entries in the Chronological Check-list given as an appendix, where current British Library shelfmarks are quoted for all early imprints. Gulf of Newfoundland St. Lawrence P Québec assamaquoddy Canada Eastern Abenaki Micmac W USA Abenakiestern Maliseet Mahican ● Boston Munsee Delaware Massachusett Narragansett Unami Delaware ● Mohegan-Pequot Quiripi-Unkechaug Washington ● New York Nanticoke-Conoy Virginia Algonquian Carolina Algonquian Fig. 1. Map showing the habitations of speakers of the Algonquian language family. -

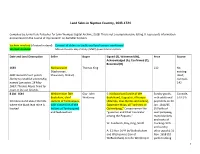

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Colonial Times on Buzzard's Bay

mw fa noll mJI BRIGHT LEGACY ODe half tile IDCOlDe froID tb1I Leaaer. "b1eh .... re ee1..ed 10 .810 oDder tile "W of JONATHAN BIlOWN BIlIGHT of WoItIwo. M_hoa.tu.1oto be ellpeDd.d for bookl for tile CoU. Library. The otller half of til. IDcolDe :e:::t::d~=h.r 10 H....... UDI...nltyfortll. HINIlY BIlIGHT. JIl•• "ho cIIed at Waterto..... MaaadI_.10'686. 10 til. aboeDCD of loch deoceodootl. otller penoD' oro eUpbl. to til. ocbolanhlpo. Th.,,1U reqolreo tIIat t1110 100000_ lDeDt Ihall be ...... 10 ...ery book "ded to tile Library ....r Ito ,rorioIooo. .... ogle R FROM THE- BRIGHT LEGACY. Descendants of Henry Brifl'hl, jr., who died at Water. town,MasS., in J6S6,are entitled to hold scholarships in Harvard College, established in ,830 under the wil,-of JONATHAN BROWN BRIGHT of Waltham, Mass., with one half the income of this l.egacy. ~uch descendants failing, other persons are eligible to the scholarships. The will requires that this a.I)nOUDcement shall be made in every book added'" to the Library under its provisions. Received £ j Coogle COLONIAL TIMES ON BUZZARD'S BAY BY WILLIAM ROOT BLISS ..ThIs Is the place. Stand still, my steed, Let me review the scene, And summon from the shadowy Put The (ClI1IllI lhat once haye been.It LoKGnLLOW. / ,'BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY _fie flitl~ibe tl'rr-" ftam~ 1888 Dig; Ized by Google Copyright, .888, By WILLIAM ROOT BLISS. Tlu RirJlf',iu P...... Ca..u..itl,p: Electrotyped and Printed by H. O. Houghton 8: Co. -

Joanna Cotton: an Unexpected (Proto-) Egalitarian Jason Eden in 1664, a Young Puritan Minister Named John Cotton Jr

Joanna Cotton: An Unexpected (Proto-) Egalitarian Jason Eden In 1664, a young Puritan minister named John Cotton Jr. was strict gender norms and precise restrictions upon women’s lead- found guilty of “lascivious unclean practices with three wom- ership opportunities. en.”1 Mr. Cotton was a Harvard graduate, a descendant of well- One of the ways in which Joanna Cotton escaped subordina- respected parents, and a husband and father. As a punishment for tion to the men in her life was by developing her own distinctive his sinful deeds, English officials in Massachusetts forced Cot- Christian faith. Sufficient documentation exists to support cer- ton to give up his pastorate of a local church. The question was, tain conclusions regarding her religious beliefs, household du- what could he do to support Joanna, his wife, and their children? ties, and emotional state. This article, in examining these aspects Puritan leaders found the answer in an unlikely place: Martha’s of her life, argues that Joanna’s beliefs and behavior often differed Vineyard. For many years, members of the Mayhew family had substantially from those of her husband. She regularly functioned labored as missionaries on the island, trying to teach local Indi- at the edges of what some scholars describe as a “culture of won- ans about Christianity. The Mayhews needed help, and John Cot- ders” that pervaded popular religious expression in colonial New ton Jr. was sufficiently qualified, in the eyes of the English at least, England.7 Though she was far from a heretic, Joanna worked as to preach to Indians. -

Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: an Authoritative Edition

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 1-12-2005 Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative Edition Paul Melvin Wise Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Wise, Paul Melvin, "Cotton Mathers's Wonders of the Invisible World: An Authoritative Edition." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2005. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COTTON MATHER’S WONDERS OF THE INVISIBLE WORLD: AN AUTHORITATIVE EDITION by PAUL M. WISE Under the direction of Reiner Smolinski ABSTRACT In Wonders of the Invisible World, Cotton Mather applies both his views on witchcraft and his millennial calculations to events at Salem in 1692. Although this infamous treatise served as the official chronicle and apologia of the 1692 witch trials, and excerpts from Wonders of the Invisible World are widely anthologized, no annotated critical edition of the entire work has appeared since the nineteenth century. This present edition seeks to remedy this lacuna in modern scholarship, presenting Mather’s seventeenth-century text next to an integrated theory of the natural causes of the Salem witch panic. The likely causes of Salem’s bewitchment, viewed alongside Mather’s implausible explanations, expose his disingenuousness in writing about Salem. Chapter one of my introduction posits the probability that a group of conspirators, led by the Rev. -

Ancestry of Alice Maud Clark – an Ahnentafel Book

Ancestry of Alice Maud Clark – An Ahnentafel Book - Including Clark, Derby, Fiske, Bixby, Gilson, Glover, Stratton and other families of Massachusetts by A. H. Gilbertson 8 January 2021 version 0.154 © copyright A. H. Gilbertson, 2012-2021 © copyright 2016-2021 A. H. Gilbertson Table of Contents Preface............................................................................................................................................. 5 Alice Maud Clark (1) ...................................................................................................................... 6 John Richardson Clark (2) and Caroline Maria Derby (3) ............................................................. 9 Horatio Clark (4) and Betsey Bixby (5) ........................................................................................ 13 John Derby (6) and Martha Fiske (7) ............................................................................................ 16 Moses Clark (8) and Martha Rogers (9) ....................................................................................... 18 Asa Bixby (10) and Lucy Gilson (11)........................................................................................... 20 John Derby (12) and Mary Glover (13) ........................................................................................ 22 Robert Fiske (14) and Nancy Stratton (15) ................................................................................... 23 Norman Clark (16) and Hannah Bird (17) ...................................................................................