Jerry Woodfill (May 8, 2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro Personnel at the Mission Operations Directorate at the Johnson

STORY | ASK MAGAZINE | 13 Plan,Train,and Fly: MISSION OPERATIONS FROM APOLLO TO SHUTTLE BY JOHN O'NEILL Intro Personnel at the Mission Operations Directorate at the Johnson Space Center are the final integrators of the planning and execution steps that must occur to get from mission definition and design to flight. Over the years, the technology of some of this essential work has changed, but the general principles and the dedication and skill of those doing it remain the same. A brief look at the history of planning, training, and flying—the three related functions within human space flight mission operations—will make some of the challenges clear and show how we met them in the past and how we meet them today. On NASA Kennedy Space Center’s Shuttle Landing Facility, the Shuttle Training Aircraft (STA) takes to the skies. The STA is a Grumman American Aviation–built Gulf Stream II jet that was modified to simulate an orbiter’s cockpit, motion and visual cues, and handling qualities. In flight, the STA duplicates the orbiter’s atmospheric descent trajectory from approximately 35,000 ft. altitude to landing on a runway. Because the orbiter is unpowered during reentry and landing, its high-speed glide must be perfectly executed the first time. Photo Credit: NASA sticky-back Velcro was not yet available; when the cue cards were John C. Houbolt at a blackboard, showing rendezvous concept for lunar landings. Lunarhis Orbital space finalized, an adhesive was used to attach the specially shaped Rendezvous was used in the Apollo program. Velcro to the cards. -

NASA's BEST Activities

NASA’s BEST Activities Beginning Engineering Science and Technology An Educators Guide to Engineering Clubs Grades 3–5 Table of Contents General Supplies List for Activities 1–12 .................................................................... 3 Lesson Plan Cover Page ............................................................................................ 12 Activity #1: Build a Satellite to Orbit the Moon!........................................................ 15 Activity #2: Launch Your Satellite! ............................................................................ 26 Teacher Notes for Activities 3–5:......................................................................... 37 Activity #3: Design a Lunar Rover!............................................................................ 38 Activity #4: Design a Landing Pod! ........................................................................... 46 Activity #5: Landing the Rover! ................................................................................. 55 Teacher Notes for Activities 6–7:......................................................................... 61 Activity #6: Mission: Preparation! ............................................................................. 62 Activity #7: Ready, Set, Explore! ............................................................................... 74 Teacher Notes for Activities 8 and 9: .................................................................. 77 Activity #8: Crew Exploration Vehicle ...................................................................... -

CHAPTER 9: the Flight of Apollo

CHAPTER 9: The Flight of Apollo The design and engineering of machines capable of taking humans into space evolved over time, and so too did the philosophy and procedures for operating those machines in a space environment. MSC personnel not only managed the design and construction of space- craft, but the operation of those craft as well. Through the Mission Control Center, a mission control team with electronic tentacles linked the Apollo spacecraft and its three astronauts with components throughout the MSC, NASA, and the world. Through the flights of Apollo, MSC became a much more visible component of the NASA organization, and oper- ations seemingly became a dominant focus of its energies. Successful flight operations required having instant access to all of the engineering expertise that went into the design and fabrication of the spacecraft and the ability to draw upon a host of supporting groups and activities. N. Wayne Hale, Jr., who became a flight director for the later Space Transportation System (STS), or Space Shuttle, missions, compared the flights of Apollo and the Shuttle as equivalent to operating a very large and very complex battleship. Apollo had a flight crew of only three while the Shuttle had seven. Instead of the thousands on board being physically involved in operating the battleship, the thousands who helped the astronauts fly Apollo were on the ground and tied to the command and lunar modules by the very sophisticated and advanced electronic and computer apparatus housed in Mission Control.1 The flights of Apollo for the first time in history brought humans from Earth to walk upon another celes- tial body. -

Build It with Spacewalks Poster

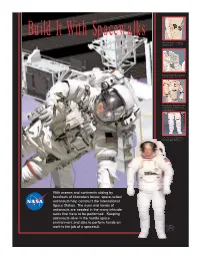

Build It With Spacewalks Small, water-filled, plastic tubes laced through the liquid cooling and vent garment keep the astronaut cool inside a spacesuit. When pressurized, spacesuits become stiff. Suit gloves need many joints to permit finger dexterity. A small wrist mirror permits reading control settings on the front of the suit. With the outer suit fabric removed, bearings for mobility are visible in the shoulders, wrist, and waist. The astronaut enters the suit by pulling on the lower torso (pants), slipping into the upper torso, and snapping the waist bearing rings together. The lower torso has boots attached.Red stripes on some suits help mission controllers identify which astronaut they are looking at in their television screens. With oceans and continents sliding by hundreds of kilometers below, space-suited astronauts help construct the International Space Station. The eyes and hands of astronauts are needed in the many intricate tasks that have to be performed. Keeping astronauts alive in the hostile space environment and able to perform hands-on Fully suited, the astronaut is ready for work is the job of a spacesuit. a space walk. Refer to the other side of the poster for more suit details. Build it with Spacewalks 2005 AD Just after sunset, an exceptionally bright star-like object glitters in the southwestern sky. Unlike its stellar background, the object moves quickly and sets in the northeast a few minutes after it first appeared. It is a scene that is repeated over many parts of Earth 16 times each day. The object is the International Space Station, a huge orbital space platform constructed by the United States, Russia, Canada, Japan, Brazil, and 11 European nations. -

Toll Free 1800 805

TOLL FREE 1800 805 502 WWW.SOUTHERNCROSSTAPES.COM.AU Southern Cross Tapes have been supplying the Australian market with high quality products and services for over 20 years. Our comprehensive range includes products to cater for all industries and our customer focused, results driven team have the knowledge to assist with all your enquiries. Our huge range includes packaging, cloth, masking, trade and specialised tapes along with a large range of accessories. We are committed to being market leaders with a complete innovative product range. Due to our extensive market knowledge, relationships, sourcing and reputation we have been chosen to represent a number of the highest quality international brands including Nichiban, Nitto and Cantech. Our dedicated sales team understand that in today’s competitive business world, superior customer service is vitally important. Our experienced team will work with you personally to provide the best possible solution to meet your individual needs. If you are looking for expert advice, competitive pricing, quick turn around and reliable delivery you’ve come to the right place - SOUTHERN CROSS TAPES. DISCLAIMER: the colours shown in this brochure may not exactly match the colours (ink or colour of product) of the actual product. “Whatever your industry, whatever your application, we are confident we have the tape for you”. CONTENTS Nichiban Premium Tape Products 4 735 - Premium Polypropylene Packaging Tape 120 - Premium Cloth and Binding Tape 652 - Premium Double Sided Cloth Tape 335 - Panfix Premium -

Shoot for the Moon: the Space Race and the Extraordinary Voyage of Apollo 11

Shoot for the Moon: The Space Race and the Extraordinary Voyage of Apollo 11 Hardcover – March 12, 2019 By James Donovan (Author) „It does not really require a pilot and besides you have to sweep the monkey shit aside before you sit down” a slightly envious Chuck Yeager is quoted in chapter 2 of the book, titled “Of Monkeys and Men”. In the end, the concept to first send monkeys as forerunners for humans into space was right: with a good portion of luck, excellently trained test pilots, who were not afraid to put their lives on the line, dedicated managers and competent mission control teams Kennedy's bold challenge became true. This book by James Donovan was published in 2019 for the 50the anniversary of the first landing of the two astronauts Neil Armstrong and “Buzz”Aldrin on the Moon. The often published events are re-told in a manner making it worthwhile to read again as an “eye witness” but it serves also as legacy for the next generations. The author reports the events as a thoroughly researched adventure but also has the talent to tell the events like a close friend to the involved persons and astronauts and is able to create the resentments, fears and feelings of the American people with respect to “landing a man on the Moon and bring him back safely” over the time period which was started by the “Sputnik-shock” in 1957. The book can also be seen as homage of the engineers, scientists and technicians bringing the final triumph home. -

Interview Transcript

ORAL HISTORY 2 TRANSCRIPT EUGENE F. KRANZ INTERVIEWED BY REBECCA WRIGHT HOUSTON, TEXAS – 8 JANUARY 1999 WRIGHT: Today is January 8, 1999. We are visiting with Eugene F. Kranz in the offices of SIGNAL Corporation, Houston, Texas, for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. The interview team is Rebecca Wright, Carol Butler, and Sasha Tarrant. Good morning, and thanks again for taking your time. We appreciate you doing a second oral history with this project, and today we'd like to focus on your involvement with the Apollo Program, which we feel is somewhat apropos, because in just a few months we're going to be noting the thirtieth anniversary of the first manned lunar landing. You've already shared your experiences, some of your experiences, with us on the early missions of the Apollo Program. So we'd like for you to begin today by telling us some of the preparations and the training that were needed to set that stage for the historic mission. KRANZ: Are you speaking specifically of the Apollo 11 mission or are you talking about the transition from Gemini to the Apollo Program? Because that's about where the other interview ended. WRIGHT: That's where we'd like for you to pick up. KRANZ: I was working as a flight director on the Gemini IX mission, and it seemed almost overnight I was picking up the responsibilities for the Apollo Program. [Christopher C.] Chris 8 January 1999 13-1 Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Eugene F. Kranz Kraft, myself, and John Hodge were to be the first flight directors to fly the first manned Apollo mission. -

Nothing Routine!

Nothing Routine (About the Scope of Advent’s Mission) Consequently, when Christ came into the world, he said . (Hebrews 10:5) A sermon by Siegfried S. Johnson on the First Sunday of Advent, December 3, 2017 (Volume 1 Number 20) Christ of the Hills UMC, 700 Balearic Drive, Hot Springs Village, Arkansas 71909 Forty-five Advent’s ago, December 14, 1972, the crew of the Apollo 17 Lunar Landing Module, Commander Eugene Cernan and geologist Harrison Schmitt, lifted off the lunar surface to initiate their return to earth. These were the last astronauts to add footprints to the dusty lunar surface. We haven’t been back. It had only been three years earlier, that memorable summer of 1969, that Neil Armstrong spoke the words, “The Eagle has landed,” as Apollo 11’s landing module touched down on the moon’s surface. We frequented the moon between 1969 and 1972, but no American under forty-five years old has been alive for the ADVENT-ure of a manned flight to the moon. Space adventures don’t garner the saturated news coverage they once did. I suspect, for example, most here are unaware of this coming Friday’s launch from Cape Canaveral on a cargo mission to rendezvous with the International Space Station. I doubt, also, that any here are anxiously waiting our next manned space adventure launching two weeks from today, December 17. Called Expedition 54, this mission will carry a new crew to the ISS -- an American, a Russian, and a Japanese astronaut. Did you know about these imminent launches? No? I didn’t know, either. -

Admissibility Package for Tape All Wrapped Up

Admissibility Package for Tape all Wrapped Up Mark A. Ahonen Presentation Objectives • PowerPoint presentation to educate appropriate personnel • Current status of SWGMAT tape documents • Admissibility package for court purposes • Tape bibliography, tape survey, sourcing bibliography with comments Presentation Disclaimers • The admissibility package presentation today will not be given the same way I would deliver it in a court proceeding • Take out the first four slides • Many of the slides will not be discussed in detail • Some of the ideas and topics of the presentation were taken from others Presentation Notes • An attempt was made to have a ‘generic’ admissibility package presentation that would be fairly applicable to all laboratories • Common sense slides will be discussed briefly to help with purpose • A modification would be needed for: • Laboratories with a completely different analysis scheme • If sourcing is the main emphasis Admissibility Package - Tape Pressure Sensitive Tape as Physical Evidence • Associating one person, place, or thing with another person place or thing (i.e. common origin) • Verifying a story or as an investigative lead. (i.e. sequencing, sourcing) TapeTape –– AssociativeAssociative EvidenceEvidence Involves the comparison of samples to determine if they could share a common origin The goal is to determine if any significant differences exist TapeTape -- DefinitiveDefinitive AssociationAssociation An end match provides a definitive association to an individual source A physical end match is the most compelling type of association between two tapes and should always be evaluated. Sequencing • End matching pieces of tape can tell the sequence of events in the use of that particular roll (e.g. legs taped first, then arms) • If tape is cut – the multiple pieces of duct tape can still be attempted to be sequenced Sourcing • An attempt to identify possible product information, manufacturing, and retailing sources can provide investigative lead information. -

Apollo 11: First Steps Edition

APOLLO 11: FIRST STEPS EDITION Sensory Friendly Script The Omnitheater has a rotating Dome Screen. It begins above the audience. Four minutes before the show starts, it will begin rotating to the movie position down in front of the audience. You will hear a few LOUD BANGS as it rotates. The movie will projected onto the Dome Screen after it has finished rotating. This movie has editing that can sometimes be quick and feel disorientating. There is no one narrator, instead it is narrated by those who have experienced it firsthand. As a result, sound often changes abruptly from scene to scene, and sound can make sudden changes from quiet to loud. Please return to an Omnitheater Associate after the show. APOLLO 11: FIRST STEPS EDITION—47MINUTES SENSORY SCENE DESCRIPTION DIALOGUE/SOUND COMMENTS EXT. DESERT—DAY. Aerial shot of We have been here before desert. FAST PACED In the dreams of the ancients IMAGES FOR THE CUT TO: Alternate aerial shot of who traced the stars in pools 30 SECONED desert by moonlight, COMMERCIAL! CUT TO: Alternate aerial shot of desert CUT TO: Push in over steering And the chalkboards of wheel scientists CUT TO: Hands curling over steering wheel who plotted a course. CUT TO: Ignition button being pushed CUT TO: Wheel locked off center frame while car rotates around it Car driving vertically. Frame rotates horizontally CUT TO: M/S through passenger window of woman driving car CUT TO: Aerial shot of car driving through desert CUT TO: Alternate aerial shot of car driving through desert It’s a journey they started, CUT TO: Foot steps onto desert surface And one we must continue. -

Pressure Sensitive Tapes for Industrial Insulation and General Purpose

www.gltproducts.com Pressure Sensitive Tapes for Industrial Insulation and General Purpose Insulation Innovation Abatement Industrial Packaging Building & Construction Duct HVAC Jacketing Systems Masking Mechanical Closure Systems Plumbing Repair Thermal Insulation Mechanical Closure Tapes ASJ and FSK TAPES FSK Facing Tape Non-Adhesive FSK Facing Tridirectionally reinforced with fiber- Uncoated, flame resistant glass scrim, UL listed Foil Scrim Kraft aluminum Foil Scrim Kraft lamination. Coated with a special lamination with 2 x 3/sq. in. cold weather acrylic adhesive system. tridirectional scrim pattern. Combines quick stick at normal temperatures with superior low- temperature performance. Recom- mended for use down to 10°F (-12°C). Meets ASTMC1136. Application: Vapor barrier paper over plain fiberglass Application: Vapor seal on FSK faced fiberglass duct board and other insulation products and blanket systems Thickness: 3.5 mils (80 µ) Thickness: 6.5 mils (165 µ) (exclusive of liner) Widths: 42, 48, 50, 54, 71 inches Widths: 2, 3, 4, 5 inches Lengths: 150, 200, 600, 900 feet on 3 inch core Lengths: 50, 100 yards on 3 inch core Non-Adhesive ASJ Facing Tape ASJ Facing Tape Uncoated barrier material consisting White Foil Scrim Kraft lamintion of flame resistant, high-intensity white with 4 x 4/sq.in. tridirectional kraft paper, fiberglass yarn reinforce- scrim pattern. Special cold ment and aluminum foil lamination. weather acrylic adhesive Scrim: 5 x 5/sq. in. tridirectional system, with mold inhibiting pattern. agents to help prevent mold under the insulation. Combines quick stick at normal temperatures with low- Application: Vapor barrier paper for all types of insulation temperature performance Widths: 3, 23½, 35½, 48, 71 inches down to -25°F (-32°C). -

Lunar Nautics: Designing a Mission to Live and Work on the Moon

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lunar Nautics: Designing a Mission to Live and Work on the Moon An Educator’s Guide for Grades 6–8 Educational Product Educator’s Grades 6–8 & Students EG-2008-09-129-MSFC i ii Lunar Nautics Table of Contents About This Guide . 1 Sample Agendas . 4 Master Supply List . 10 Survivor: SELENE “The Lunar Edition” . 22 The Never Ending Quest . 23 Moon Match . 25 Can We Take it With Us? . 27 Lunar Nautics Trivia Challenge . 29 Lunar Nautics Space Systems, Inc. ................................................. 31 Introduction to Lunar Nautics Space Systems, Inc . 32 The Lunar Nautics Proposal Process . 34 Lunar Nautics Proposal, Design and Budget Notes . 35 Destination Determination . 37 Design a Lunar Lander . .38 Science Instruments . 40 Lunar Exploration Science . 41 Design a Lunar Miner/Rover . 47 Lunar Miner 3-Dimensional Model . 49 Design a Lunar Base . 50 Lunar Base 3-Dimensional Model . 52 Mission Patch Design . 53 Lunar Nautics Presentation . 55 Lunar Exploration . 57 The Moon . 58 Lunar Geology . 59 Mining and Manufacturing on the Moon . 63 Investigate the Geography and Geology of the Moon . 70 Strange New Moon . 72 Digital Imagery . 74 Impact Craters . 76 Lunar Core Sample . 79 Edible Rock Abrasion Tool . 81 i Lunar Missions ..................................................................83 Recap: Apollo . 84 Stepping Stone to Mars . 88 Investigate Lunar Missions . 90 The Pioneer Missions . 92 Edible Pioneer 3 Spacecraft . .96 The Clementine Mission . .98 Edible Clementine Spacecraft . .99 Lunar Rover . 100 Edible Lunar Rover . 101 Lunar Prospector . 103 Edible Lunar Prospector Spacecraft . 107 Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter . 109 Robots Versus Humans . 11. 1 The Definition of a Robot .