C2D Working Paper Series 2006/1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Survey of Residents of Ukraine

Public Opinion Survey of Residents of Ukraine May 26-June 10, 2018 Methodology • The survey was conducted by Rating Group Ukraine on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research. • The survey was conducted throughout Ukraine (except for the occupied territories of Crimea and Donbas) from May 26–June 10, 2018, through face-to-face interviews at respondents’ homes. • The sample consisted of 2,400 permanent residents of Ukraine aged 18 and older and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by gender, age, region, and settlement size. The distribution of population by regions and settlements is based on statistical data of the Central Election Commission from the 2014 parliamentary elections, and the distribution of population by age and gender is based on data from the State Statistics Committee of Ukraine from January 1, 2017. • A multi-stage probability sampling method was used with the random route and next birthday methods for respondent selection. • Stage One: The territory of Ukraine was split into 25 administrative regions (24 regions of Ukraine and Kyiv). The survey was conducted throughout all regions of Ukraine, with the exception of the occupied territories of Crimea and Donbas. • Stage Two: The selection of settlements was based on towns and villages. Towns were grouped into subtypes according to their size: • Cities with populations of more than 1 million • Cities with populations of between 500,000-999,000 • Cities with populations of between 100,000-499,000 • Cities with populations of between 50,000-99,000 • Cities with populations of up to 50,000 • Villages Cities and villages were selected by the PPS method (probability proportional to size). -

Ukraine Election: Comedian Zelensky Wins Presidency by Landslide - BBC News

Ukraine election: Comedian Zelensky wins presidency by landslide - BBC News Menu Home Video World US & Canada UK Business Tech Science Stories World Africa Asia Australia Europe Latin America Middle East Ukraine election: Comedian Zelensky wins presidency by landslide 22 April 2019 Share Ukrainian presidential election 2019 Volodymyr Zelensky and his supporters celebrate winning Ukraine's presidential election Ukrainian comedian Volodymyr Zelensky has scored a landslide victory in the country's presidential election. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-48007487[12/15/2019 9:28:06 AM] Ukraine election: Comedian Zelensky wins presidency by landslide - BBC News With nearly all ballots counted in the run-off vote, Mr Zelensky had taken more than 73% with incumbent Petro Poroshenko trailing far behind on 24%. "I will never let you down," Mr Zelensky told celebrating supporters. Russia says it wants him to show "sound judgement", "honesty" and "pragmatism" so that relations can improve. Russia backs separatists in eastern Ukraine. The comments came from Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, in a Facebook post on Monday (in Russian). He said he expected Mr Zelensky to "repeat familiar ideological formulas" that he used in the election campaign, adding: "I have no illusions on that score. "At the same time, there is a chance to improve relations with our country." Mr Poroshenko, who admitted defeat after the first exit polls were published, has said he will not be leaving politics. He told voters that Mr Zelensky, 41, was too inexperienced to stand up to Russia effectively. Mr Zelensky, a political novice, is best known for starring in a satirical television series Servant of the People, in which his character accidentally becomes Ukrainian president. -

Public Opinion Survey of Residents of Ukraine

Public Opinion Survey of Residents of Ukraine March 15-31, 2018 Methodology • The survey was conducted by Rating Group Ukraine on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research. • The survey was conducted throughout Ukraine (except for the occupied territories of Crimea and Donbas) from March 15-31, 2018, through face-to-face interviews at respondents’ homes. • The sample consisted of 2,400 permanent residents of Ukraine aged 18 and older and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by gender, age, region, and settlement size. The distribution of population by regions and settlements is based on statistical data of the Central Election Commission from the 2014 parliamentary elections, and the distribution of population by age and gender is based on data from the State Statistics Committee of Ukraine from January 1, 2017. • A multi-stage probability sampling method was used with the random route and next birthday methods for respondent selection. • Stage One: The territory of Ukraine was split into 25 administrative regions (24 regions of Ukraine and Kyiv). The survey was conducted throughout all regions of Ukraine, with the exception of the occupied territories of Crimea and Donbas. • Stage Two: The selection of settlements was based on towns and villages. Towns were grouped into subtypes according to their size: • Cities with population of more than 1 million • Cities with population of between 500,000-999,000 • Cities with population of between 100,000-499,000 • Cities with population of between 50,000-99,000 • Cities with population up to 50,000 • Villages Cities and villages were selected by PPS method (probability proportional to size). -

Faltering Fightback: Zelensky's Piecemeal Campaign Against Ukraine's Oligarchs – European Council on Foreign Relations

POLICY BRIEF FALTERING FIGHTBACK: ZELENSKY’S PIECEMEAL CAMPAIGN AGAINST UKRAINE’S OLIGARCHS Andrew Wilson July 2021 SUMMARY Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, has declared a “fightback” against oligarchs. Zelensky is motivated by worries about falling poll ratings, pressure from Russia, and a strong desire for good relations with the Biden administration. The fightback campaign has resulted in action against some oligarchs but, overall, it is incomplete. The government still needs to address reform issues in other areas, especially the judiciary, and it has an on-off relationship with the IMF because of the latter’s insistence on conditionality. The campaign has encouraged Zelensky’s tendency towards governance through informal means. This has allowed him to act speedily – but it risks letting oligarchic influence return and enabling easy reversal of reforms in the future. Introduction On 12 March this year, Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, released a short appeal on YouTube called “Ukraine fights back”. He declared that he was preparing to take on those who have been undermining the country – those who have exploited Ukraine’s weaknesses in particular, including its frail rule of law. He attacked “the oligarchic class” – and named names: “[Viktor] Medvedchuk, [Ihor] Kolomoisky, [Petro] Poroshenko, [Rinat] Akhmetov, [Viktor] Pinchuk, [Dmitry] Firtash”. He proceeded to address the oligarchs directly, asking, “Are you ready to work legally and transparently?” The president went on, “Or do you want to continue to create monopolies, control the media, influence deputies and other civil servants? The first is welcome. The second ends.” Ukrainians have heard this kind of talk before. Zelensky’s predecessor, Poroshenko, also made ‘de- oligarchisation’ a policy pledge. -

OSW Commentary

Centre for Eastern Studies NUMBER 306 | 24.07.2019 www.osw.waw.pl To serve the people – total power in Zelensky’s hands Tadeusz Iwański The key slogans of the campaign of Volodymyr Zelensky and his party Servant of the People ahead of the presidential and parliamentary elections were: to bring fresh blood into the po- litical class and to introduce honest professionals to politics who have not been discredited. The new president had no political experience whatsoever and, as a result of the parliamenta- ry election, over three quarters of the seats in the Verkhovna Rada (the Ukrainian parliament) will be taken by individuals who have never served as members of parliament. The new parlia- ment will have the lowest average age of its deputies since 1991 and the largest proportion of women (around 20%). The largest number of new and young politicians has been introduced to the Verkhovna Rada by the Servant of the People party and the Voice party. The sweeping victory attained by Zelensky’s party will allow it to form a government by itself. The president has announced that a new prime minister will be an economist “without polit- ical experience”, and it can be assumed that this principle will also apply during the selection of most of the new ministers. Thus Ukraine, being at war with Russia and struggling with low economic growth, will be governed by individuals who are new to politics. This situation, be- ing an effect of the high hopes and expectations of the Ukrainian public for a fundamental change of the system, is giving rise to the significant potential for positive changes but also might put the political stability and further development of the Ukrainian state at risk. -

OSW Commentary

OSW Commentary CENTRE FOR EASTERN STUDIES NUMBER 334 20.05.2020 www.osw.waw.pl Neither a miracle nor a disaster – President Zelensky’s first year in office Tadeusz Iwański, Sławomir Matuszak, Krzysztof Nieczypor, Piotr Żochowski 20th May marked the end of Volodymyr Zelensky first year as President of Ukraine. Thanks to the clear victory of his Servant of the People party in the snap parliamentary election held in July 2019 and the establishment of the government of Oleksiy Honcharuk the following month, Zelensky swiftly gained full power. The plan for the declared repair of the country and an end to the war in the Donbas involved the appointment of apolitical specialists for key positions in the government to immediately process legislation in the parliament and to conduct informal diplomacy. This strategy brought about certain successes. Partial organisational changes were introduced in the prosecutor’s office and courts; the constitution was amended in the area of the rights of the members of the Verkhovna Rada and the president, and a meeting – the first in three years – in the Normandy Format was held in Paris. Already before the end of 2019 a new election law was passed, a key reform in the gas sector (the unbundling of Naftogaz) was completed and in March 2019, and a breakthrough law regarding the lifting of the moratorium on the sale of agricultural land was passed. However, increasing conflicts of interests inside the parliamentary group of the Servant of the People limited the comfort of governing the country, exposing the most important weaknesses of Zelen- sky’s bloc: its lack of ideological cohesion, the lack of a clear action plan and, above all, the lack of a professional and independent staff base. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2020

INSIDE: l Human rights activist Raisa Rudenko dies at 80 – page 3 l Our community: Alberta and Illinois – pages 11 and 14 l Sports: gymnastics, futsal, volleyball and more – page 16 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXXVIII No. 41 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY,OCTOBER 11, 2020 $2.00 NEWS ANALYSIS Ukraine battles massive fires In Ukraine: Heading for a fall? in Luhansk region the Parliament, nor guarantee satisfactory by Bohdan Nahaylo returns in the upcoming local elections. In Ukrainian politics, a sluggish season The disturbing feature here is that pro-Rus- has given way to another, but one that sian forces have been profiting from this promises reinvigoration, though not neces- and gaining relatively more strength than sarily of the healthy sort. others. In Ukraine there has been no noticeable One of the telling features of real democ- change in the lackadaisical approach to pol- racy in Ukraine – unlike in neighboring itics and reform, and in the general situa- Russia, or Belarus, or Kyrgyzstan – elec- tion as such. It has been largely a case of tions are genuinely free and the results are business as usual as per the lethargic respected, and independent opinion and Ukrainian variant that we have become exit polls are accurate and can be trusted. used to. The only sphere where there has The latest polling been more dynamism is in the external one, Cabinet of Ministers with two important and productive In mid-September, the Kyiv International A firefighter works on extinguishing a fire in one of the 146 hotspots in Ukraine’s east. -

The Ukrainian Weekly, 2021

Part 1 of THE YEAR IN REVIEW pages 7-15 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXXIX No. 3 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 17, 2021 $2.00 New twist in Sheremet murder case as audio U.S. sanctions more Ukrainians suspected recording allegedly implicates Belarusian KGB of interfering in 2020 presidential election by Mark Raczkiewycz repeated public statements to advance dis- information narratives that U.S. govern- KYIV – The U.S. Treasury Department on ment officials have engaged in corrupt January 11 sanctioned several Ukrainian dealings in Ukraine.” individuals and entities linked to a Verkhovna In a separate statement, Secretary of Rada lawmaker that a Washington intelli- State Mike Pompeo said that Mr. Derkach gence agency says is a Russian agent who “has been an active Russian agent for more allegedly attempted to influence the 2020 than a decade, maintaining close connec- U.S. presidential election. tions with Russian intelligence services.” Joining lawmaker and suspected Russian A graduate of the Soviet Union’s KGB agent Andriy Derkach, who does not belong academy, Mr. Derkach was sanctioned in to a political party, on the department’s August for “spreading claims about corrup- “Specially Designated Nationals List” is tion – including through publicising leaked Oleksandr Dubinsky, who leads the party phone calls – to undermine former Vice- Servant of the People. President Biden’s candidacy and the Mr. Dubinsky previously worked for bil- Democratic Party,” Director of the National RFE/RL lionaire oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky’s 1+1 Counterintelligence and Security Center television channel, which provided favor- A sign asking “Who killed Pavlo?” in front of the new memorial to Pavlo Sheremet in (NCSC) William Evanina said in a news Kyiv. -

UKRAINIAN PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES Populist Volodymyr Zelensky Is Currently Leading in the Polls with 25% to 27%

UKRAINIAN PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES Populist Volodymyr Zelensky is currently leading in the polls with 25% to 27%. Current Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko are tied for second with roughly 15% to 18%. Pro-Russian Yuriy Boyko is polling fourth with 9% to 13%. All other candidates are trailing in the polls. Polling data is based on a survey of recent poll results.1 Chart citations can be found on the ISW Research Blog. General Information Political Positions Likelihood of Advancing Russia’s Goals Petro Poroshenko POROSHENKO BLOC “SOLIDARITY” Running as Independent2 Poroshenko is unlikely given his history to make voluntary concessions to • Key supporter of Ukraine’s Russia. The Kremlin has likely already expended most of its existing leverage integration into the EU and on Poroshenko. NATO Russia would likely continue to intensify its military provocations and other • Incumbent President • Strong opponent of the forms of pressure on Ukraine in the event of a victory by Poroshenko. It • Founder of Roshen, the largest Kremlin in Ukraine would also likely attempt to limit his presidential powers through the election chocolate company in Ukraine3 • Suffers from negative public of favorable candidates in the Ukrainian Parliament. • Supported Euromaidan ratings due largely to failed Poroshenko stands to hold a diminished ability to shape policy even if he wins Revolution in 20144 anti-corruption reforms reelection. His popular support is slipping and he would likely win only by a slim margin. His bloc also stands to lose ground in the Ukrainian Parliament. Yulia Tymoshenko ALL-UKRAINIAN UNION “FATHERLAND” (Batkivshchyna)5 • Populist • Frames self as pro-Western Tymoshenko’s populist agenda will likely impede the economic and political and Ukrainian nationalist reforms necessary for Ukraine’s further integration with the West. -

The Ukraine List #472 Compiled by Dominique Arel Chair of Ukrainian Studies, U of Ottawa 2 September 2014

The Ukraine List #472 compiled by Dominique Arel Chair of Ukrainian Studies, U of Ottawa www.ukrainianstudies.uottawa.ca 2 September 2014 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - “Mega” Danyliw Seminar “Ukraine 2014”, Oct 30-Nov 1, uOttawa ASN 2015 20th Anniversary Convention: Call for Papers Next Week - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1- Putin Recognizes “Novorossiia” 2- Guardian: Putin Demands “Statehood” for Southeast Ukraine 3- Le Monde: Tracking the Phantom Russian Army [UKL translation] 4- Reuters: Russia Human Rights Officials Says 100 Russian Soldiers Killed 5- Negotiating with the “Rebels”: A Facebook Exchange (Kudelia et al.) 6- Washington Post: Mothers of Russian Soldiers Kept in the Dark 7- Hayla Coynash: Committee of Soldiers Mothers Branded “Foreign Agent” 8- Window on Eurasia: Russia Lacks Resources to Occupy Eastern Ukraine 9- Appeal of Polish Intellectuals to the Citizens and Governments of Europe 10- BBC: Ukraine Activist Relives Humiliation Horrors 11- UN: Excerpts from Latest Report—On Casualties, Illegal Detentions etc. 12- khpg.org: Halya Coynash, President Signs Repressive “Anti-Terrorist” Laws 13- Kyiv Post: Porochenko and His Promises, Three Months Later 14- OpenDemocracy: David Marples, The Rhetoric of Hatred Misses the Point 15- The Independent: NATO Must Refocus on Collective Defense 16- -

Distributed By

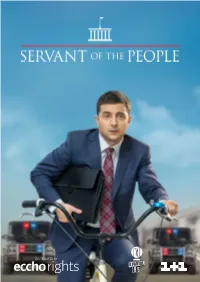

DISTRIBUTED BY What happens when an ordinary but honest man gets elected president? Servant of the People is the hilarious comedy series that answers this question - and launched the real life political career of creator Volodymyr Zelensky, elected President of Ukraine in April 2019 In the comedy series Servant Of The People, modest and humble teacher Vasily is caught on camera raging over the miserable situation in his country. When a pupil posts the video on Youtube, it becomes a viral sensation. Everybody loves Vasily’s outrage and people start gathering money for a presidential campaign. And to everybody’s surprise he gets elected. Servant of the People follows Vasily’s new life as president, how he copes with the expectations, not only from the nation but also from his family and friends. He has no interest in changing his life, he wants to stay the same, live in his flat with his parents, borrow money from his friends at the end of the month and take his bike to work; it’s just that now he goes to work as the most powerful man in the country. Will the dark forces of the establishment grind this honest and modest man down or will Vasily survive in his fight against institutionalised corruption? Servant Of The People – politics has never been so fun! GENRE LENGTH AVAILABLE AS Comedy S01: 24 x 25 min Format, finished episodes S02: 24 x 25 min and feature film S03: 24 x 25 min More than just a Following the huge success of Servant of the People, creator and leading actor Volodymyr Zelensky announced his intention comedy series! to run for president in the 2019 election - this time for real! Zelensky rode to a landslide victory on a wave of voter dissatisfaction with the previous regime, and a campaign promising an end to the corruption that his fictional creation also fights against. -

Key Findings and Recommendations of the Independent Monitoring Of

KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE INDEPENDENT MONITORING OF COVERAGE IN ONLINE MEDIA AND THE SOCIAL NETWORK FACEBOOK OF THE 2020 LOCAL ELECTORAL CAMPAIGN IN UKRAINE Rivne region Chernihiv region Volyn region Zhytomyr region Sumy region Lviv region Kyiv region Zakarpattia region Luhansk region* Vinnytsia region Chernivtsi region Donetsk region* Kyiv-2020 KEY FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE INDEPENDENT MONITORING OF COVERAGE IN ONLINE MEDIA AND THE SOCIAL NETWORK FACEBOOK OF THE 2020 LOCAL ELECTORAL CAMPAIGN IN UKRAINE Diana Dutsyk, Olga Yurkova, Design and cover by Yelyzaveta Kuzmenko, LLC Event Envoy Oleksandr Burmahin Graphics: https://mapsvg.com/ This publication was produced with the financial maps/ukraine, support of the European Union and the Council of https://ru.freepik.com. Europe. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of either party. © Council of Europe, December 2020. All rights reserved. The reproduction of extracts (up to 500 words) is Licensed to the European Union authorised, except for commercial purposes as long under conditions. as the integrity of the text is preserved, the excerpt is not used out of context, does not provide incomplete information or does not otherwise mislead the reader This publication was elaborated as to the nature, scope or content of the text. The within the framework of the source text must always be acknowledged as follows Project “EU and Council of “© Council of Europe, year of the publication”. Europe working together to support freedom of media in Ukraine” that is aimed to All other requests concerning the reproduction/ enhance the role of media, translation of all or part of the document, its freedom and safety, and should be addressed to the Directorate of the public broadcaster as an Communications, Council of Europe instrument for consensus (F-67075 Strasbourg Cedex or [email protected]).