Questions for Kumar Shahani- Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8-Rukshana Zaman.Pmd

Man In India, 95 (1) : 83-96 © Serials Publications PRACTICING DANCE AND ANTHROPOLOGY Rukshana Zaman This autoethnographical account is based on empirical fieldwork and personal experience as a dancer born in a Muslim family, and expresses the contestation of two separate world views and their reconciliation in the academic and intellectual world. Here, I trace the journey of my life - born in a Muslim family, training in Odissi dance, and becoming a performer. This autoethnography reflects on my struggles in breaking the stereotypical norms to establish my identity in a society where dancing by girls is not encouraged. The Odissi dance, dedicated to the worship of Lord Jagannath, was a temple dance practiced solely by the maharis (female temple dancers commonly known as devadasis in South India), and was a part of Hindu temple tradition. Islam as a religion does not endorse idol worship and dance and music are considered taboos. Many times, during fieldwork, values and norms were misconstructed leading to misinterpretation of cultural ethos, and I constantly had to negotiate my identity at various times. In India, many Muslim women are associated with art and dance, and some are well known in their fields, forcing one to reflect on the syncretic tradition of the sub-continent and the more liberal traditions of Islam. I My identity as an Assamese Muslim1 is always met with awed expressions. The first statement that comes my way is, “You don’t look like an Assamese, you don’t have the Mongoloid features”. The next statement is, “Oh, you don’t look like a Muslim either as you don’t have the Pathan features - neither tall nor fair skinned”. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

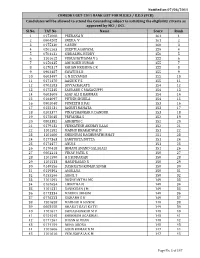

Rank List to Be Published in Web Final

Notified on 07/06/2011 COMEDK UGET2011 RANK LIST FOR M.B.B.S / B.D.S (PCB) Candidates will be allowed to attend the Counseling subject to satisfying the eligibility criteria as approved by MCI / DCI. Sl.No. TAT No Name Score Rank 1 0172008 PRERANA N 161 1 2 0804505 SNEHA V 161 2 3 0175330 S ARUN 160 3 4 0501263 DEEPTI AGARWAL 159 4 5 0704132 SIDDALING REDDY 156 5 6 1101615 PURUSHOTHAMA V S 155 6 7 0150435 ABHISHEK KUMAR 155 7 8 0170317 ROHAN KRISHNA C R 155 8 9 0902487 SWATHI S B 155 9 10 0603497 G N DEVAMSH 155 10 11 0171470 AASHIK Y S 155 11 12 0702583 DIVYACRAGATE 154 12 13 0175345 SAURABH C MASAGUPPI 154 13 14 0603609 ASAF ALI K KAMMAR 154 14 15 0164097 PIYUSH SHUKLA 154 15 16 0902048 PUNEETH K PAI 153 16 17 0155131 JAGRITI NAHATA 153 17 18 0203377 VINAYSHANKAR R DANDUR 153 18 19 0175045 PRIYANKA S 152 19 20 0803382 ABHIJITH C 152 20 21 0179132 VENKATESH AKSHAY RAAG 152 21 22 1101582 MADHU BHARADWAJ N 151 22 23 1101600 SHRINIVAS RAGHUPATHI BHAT 151 23 24 0177363 SAMYUKTA DUTTA 151 24 25 0174477 ANUJ S 151 25 26 0170418 HIMANI ANAND GALAGALI 151 26 27 0602214 VINAY PATIL S 150 27 28 1101590 H S SIDDARAJU 150 28 29 1101533 HARIPRASAD R 150 29 30 0149556 DASHRATH KUMAR SINGH 150 30 31 0159392 AMULLYA 150 31 32 0155266 AKHIL S 150 32 33 1101592 DUSHYANTHA MC 149 33 34 0167654 LIKHITHA N 149 34 35 1101531 RAVIKIRAN J M 149 35 36 0173334 MARINA AKHAM 149 36 37 0176223 RISHABH R K 149 37 38 1201628 MADHAV H HANDE 149 38 39 0603558 BHARAT RAVI KATTI 149 39 40 1101617 SHIVASHANKAR M V 148 40 41 0154545 SHUBHAM AGARWAL 148 41 42 0171261 SUSAN KURIAN 148 42 43 0174159 NEHA ARORA 148 43 44 1101606 ARUN KUMAR N M 147 44 45 1101616 VENUGOPALA K M 147 45 Page No. -

What They Say

WHAT THEY SAY What THEY SAY Mrs. Kishori Amonkar 27-02-1999 “It was great performing in the new reconstructed Shanmukhananda Hall. It has improved much from the old one, but still I’ve a few suggestions to improve which I’ll write to the authorities later” Pandit Jasraj 26-03-1999 “My first concert here after the renovation. Beautiful auditorium, excellent acoustics, great atmosphere - what more could I ask for a memorable concert here for me to be remembered for a long long time” Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra 26-03-1999 “It is a great privilege & honour to perform here at Shanmukhananda Auditorium. Seeing the surroundings here, an artiste feeling comes from inside which makes a performer to bring out his best for the art lovers & the audience.” Pandit Birju Maharaj 26-03-1999 “ yengle mece³e kesÀ yeeo Fme ceW efHeÀj DeekeÀj GmekeÀe ve³ee ©He osKekeÀj yengle Deevevo ngDee~ Deeies Yeer Deeles jnW ³en keÀecevee keÀjles ngS~ μegYe keÀecevee meefnle~” Ustad Vilayat Khan 31-03-1999 “It is indeed my pleasure and privilege to play in the beautiful, unique and extremely musical hall - which reconstructed - renovated is almost like a palace for musicians. I am so pleased to be able to play today before such an appreciative audience.” § 34 § Shanmukhananda culture redefined2A-Original.indd 34 02/05/19 9:02 AM Sant Morari Bapu 04-05-1999 “ cesjer ÒemeVelee Deewj ÒeYeg ÒeeLe&vee” Shri L. K. Advani 18-07-1999 “I have come to this Auditorium after 10 years, for the first time after it has been reconstructed. -

Catafid2010.Pdf

LES VARIÉTÉS partenaire de la 21e édition du FIDMARSEILLE 5 salles classées art & essai / recherche | café - espace expositions 37, rue Vincent Scotto - Marseille 1er | tél. : 04 91 53 27 82 Sommaire / Contents PARTENAIRES / PARTNERS & SPONSORS 005 ÉDITORIAUX / EDITORIALS 006 PRIX / PRIZES 030 JURYS / JURIES 033 Jury de la compétition internationale / International competition jury 034 Jury de la compétition française / French competition jury 040 Jury GNCR, jury Marseille Espérance, jury des Médiathèques GNCR jury, Marseille Espérance jury and Public libraries jury 046 SÉLECTION OFFICIELLE / OFFICIAL SELECTION 047 Éditorial / Editorial 048 Film d’ouverture / Opening film 052 Compétition internationale / International competition 053 Compétition premier / First film competition 074 Compétition française / French competition 101 ÉCRANS PARALLÈLES / PARALLEL SCREENS 117 Rétrospective Ritwik Ghatak 119 Anthropofolies 125 Du rideau à l’écran 157 Paroles et musique 177 Les sentiers 189 SÉANCES SPÉCIALES / SPECIAL SCREENS 221 TABLES RONDES - RENCONTRES / ROUND TABLES - MASTER CLASSES 231 FIDMarseille AVEC / FIDMarseille WITH 235 VIDÉOTHÈQUE / VIDEO LIBRARY 241 FIDLab 251 ÉQUIPE, REMERCIEMENTS, INDEX TEAM, ACKNOWLEGMENTS, INDEXES 255 C.A. et équipe FIDMarseille / FIDMarseille management committee and staff 256 Remerciements / Thanks to 257 Index des films / Film index 258 Index des réalisateurs / Filmmaker index 260 Index des contacts / Contact index 261 Partenaires / Partners & sponsors Le Festival International du Documentaire de Marseille -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

Film Studies General Course 2014

St. Xavier’s College, Calcutta [The First Autonomous College in West Bengal under University of Calcutta] FILM STUDIES GENERAL COURSE, 2014 SEM I 1A1 (FS) FS21012 Historiography 100 Marks (70+30) SEM II 1A2 (FS) FS22022 Movements 100 Marks (70+30) SEM III 1A3 (FS) FS23032 Paradigms and Practices 100 Marks (70+30) 1 SEMESTER 1 ANCILLIARY FS 1 - FS21012 Historiography (Theory: 60+10, Practical: 30) i) The Developments of Narrative Cinema Fundamentals of Film Narrative ‘Cinema of Attraction’ – Early Paradigm Transitional Cinema – Griffith Cinema of Narrative Integration –‘Classical Hollywood Cinema’ ii) Indian Popular Cinema Early Indian Cinema – Historical Approaches The Studio Era Authorship – Major Directors and Styles Popular Forms in the Post Colonial era Practical Sound Slide Project: Constructing a Narrative with Still Images Suggested Readings: Monaco, James, et al. 2000. How to Read a Film: The Art, Technology, Language, History, and Theory of Film and Media. New York: Oxford University Press. Cook, David A. 1981. A History of Narrative Film. New York: Norton. Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. 1996. Film Art: An Introduction. New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies. Hill, John, and Pamela Church Gibson. 1998. The Oxford Guide to Film Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2 Kabir, Nasreen Munni. 1996. Guru Dutt: A Life in Cinema. Delhi: Oxford University Press. Prasad, M. Madhava. 1998. Ideology of the Hindi Film: a Historical Construction. Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press. Rajadhyaksha, Ashish. Indian cinema in the time of celluloid: from Bollywood to the Emergency. Indiana University Press, 2010. SEMESTER 2 ANCILLIARY FS 2 - FS22022 Movements (Theory: 60+10, Practical: 30) i) German Expressionism Expressionist mise-en-scène: Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

A Complete Profile of Rangroop

MMMAJOR PRODUCTIONS OF RANGRANG----ROOPROOP SINCE THE INCEPTION: Total Name Of The Year No. Of Drama By Directed By Production Shows 1969-70 Michhil 12 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1972-73 Akay Akay Sunya 9 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1979-80 Kanthaswar 151 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Sanskrit play: Banabhatta; Adaptation : 1982-83 Kadambari 50 Goutam Mukherjee Dr. K.K. Chakraborty Story: Subodh Ghosh 1984-85 Andhkarer Rang 62 Script: Sima Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry Do. Prahasan 62 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry 1987-88 Clown 110 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee 1988-89 Bikalpa 74 Sima Mukhopadhyay Goutam Mukherjee Dwijen Banerjee & 1991-92 Bhanga Boned 130 Sima Mukhopadhyay Saonli Mitra 1992-93 Tringsha Shatabdi 5 Badal Sarkar Kaliprosad Ghosh 1993-94 Boli 11 Tripti Mitra Sima Mukhopadhyay 1994-95 Je Jan Achhey 187 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Majhkhane Sima Mukhopadhyay 1996-97 24 Abanindranath Tagore Aalor Phulki & K K Mukhopadhyay Panu Santi Sima Mukhopadhyay Krishna Kishore 1998-99 53 Cheyechhilo (Story: Ramanath Roy) Mukhopadhyay 1999- Aaborto 27 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2000 2000-01 Sunyapat 34 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Drama: Olwen Wymark 2002-03 Khnuje Nao 37 Adaptation: Swatilekha Sengupta Rudraprasad Sengupta Je Jan Achhey 2003-04 Majhkhane 32 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay (Revive) 2004-05 Sesh Raksha 38 Rabindranath Tagore Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2005-06 He Mor Debota 10 (Story: Deborshee Sima Mukhopadhyay Saroghee) -

Department of Public Relations, Chandigarh Administration Press Note

Department of Public Relations, Chandigarh Administration www.chandigarh.gov.in Press Note Chandigarh February 24: Department of Cultural Affairs, UT, Chandigarh is going to organize Chandigarh Dance Festival from 25 to 28 February at Tagore Theater at 7 pm daily. The following groups will perform:- 25th February 2013 Performance by Ganesa Natyalaya of Guru Saroj Vaidyanathan from Delhi. SAROJ VAIDYANATHAN Shrimati Saroj Vaidyanathan took her initial training in Bharatanayan under Shrimati Lalitha at the Saraswati Gana Nilayam in Chennai. She was later a student of the well known guru Kattumannar Muthukumaran Pillai of Thanjavur. She also studied Camatic music under Professor P. Sambamoorthy at Madras University and obtained a D.Litt in dance from the Indira Kala Sangeet Viswavidyalaya, khairagarh. Shrimati Saroj Vaidyanathan is well established today among the leading Bharatanayam teachers of the country. She is the founder director of Ganesa Natyalaya, a dance institution in Delhi where she has trained a large number of young dancers. Some of her students are among the leading artists of the younger generation. She is the recipient of seven honours including the Padma Shri given by the government of India in 2002 and recently she has been conerred with Padam Bhushan Award by Government of India. 26th February 2013 Performance by Gunjan Dance Academy of Ms. Meera Dass from Cuttack MEERA DASS At a tender age of eight, Meera had started training with Bandha Nata, an extremely acrobatic dance form in Anandapur, Keonjhar, Orissa. Meera Das was mesmerized and her eyes filled a with new future, when she saw the Odissi dance performance of Smt. -

Été Indien 10E Édition 100 Ans De Cinéma Indien

Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien Été indien 10e édition 100 ans de cinéma indien 9 Les films 49 Les réalisateurs 10 Harishchandrachi Factory de Paresh Mokashi 50 K. Asif 11 Raja Harishchandra de D.G. Phalke 51 Shyam Benegal 12 Saint Tukaram de V. Damle et S. Fathelal 56 Sanjay Leela Bhansali 14 Mother India de Mehboob Khan 57 Vishnupant Govind Damle 16 D.G. Phalke, le premier cinéaste indien de Satish Bahadur 58 Kalipada Das 17 Kaliya Mardan de D.G. Phalke 58 Satish Bahadur 18 Jamai Babu de Kalipada Das 59 Guru Dutt 19 Le vagabond (Awaara) de Raj Kapoor 60 Ritwik Ghatak 20 Mughal-e-Azam de K. Asif 61 Adoor Gopalakrishnan 21 Aar ar paar (D’un côté et de l’autre) de Guru Dutt 62 Ashutosh Gowariker 22 Chaudhvin ka chand de Mohammed Sadiq 63 Rajkumar Hirani 23 La Trilogie d’Apu de Satyajit Ray 64 Raj Kapoor 24 La complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) de Satyajit Ray 65 Aamir Khan 25 L’invaincu (Aparajito) de Satyajit Ray 66 Mehboob Khan 26 Le monde d’Apu (Apur sansar) de Satyajit Ray 67 Paresh Mokashi 28 La rivière Titash de Ritwik Ghatak 68 D.G. Phalke 29 The making of the Mahatma de Shyam Benegal 69 Mani Ratnam 30 Mi-bémol de Ritwik Ghatak 70 Satyajit Ray 31 Un jour comme les autres (Ek din pratidin) de Mrinal Sen 71 Aparna Sen 32 Sholay de Ramesh Sippy 72 Mrinal Sen 33 Des étoiles sur la terre (Taare zameen par) d’Aamir Khan 73 Ramesh Sippy 34 Lagaan d’Ashutosh Gowariker 36 Sati d’Aparna Sen 75 Les éditions précédentes 38 Face-à-face (Mukhamukham) d’Adoor Gopalakrishnan 39 3 idiots de Rajkumar Hirani 40 Symphonie silencieuse (Mouna ragam) de Mani Ratnam 41 Devdas de Sanjay Leela Bhansali 42 Mammo de Shyam Benegal 43 Zubeidaa de Shyam Benegal 44 Well Done Abba! de Shyam Benegal 45 Le rôle (Bhumika) de Shyam Benegal 1 ] Je suis ravi d’apprendre que l’Auditorium du musée Guimet organise pour la dixième année consécutive le festival de films Été indien, consacré exclusivement au cinéma de l’Inde.