Pakistan Page 1 of 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impacts of Biradarism on the Politics of Punjab: a Case Study of District Khanewal

Impacts of Biradarism on the Politics of Punjab: A Case Study of District Khanewal Shahnaz Tariq Muhammad Alamgir The aim of this study is to examine the impact of Biradarism on the politics of Punjab in general and on the politics of the Khanewal District in particular. The concept of Biradarism is defined and distinguished from the concept of caste system in the Hindu culture and society. Different aspects of Biradarism which determine the voting behaviour and pattern in the subject area are carefully viewed and analyzed. Historical, analytical and comparative methods are applied which can fairly provide a preliminary base for those who may be interested in further studies on this topic. Introduction It shall be useful if we briefly define some main concepts which form the basis of this study. Politics can be defined as an activity by which conflicting interests of various stake holders are conciliated and resolved with in a given society or political system by providing them a share and opportunity proportionate to their political significance and strength, thus achieving collective welfare and survival of the society1. Impacts of Biradarism on the Politics of Punjab: A Case Study ………….. 183 Biradari or Biradarism is derived from the Persian word Brother which means Brotherhood and can be defined as a common bandage or affiliations on the basis of religion, language, race, caste etc2. In the Subcontinent this term is used for identifying the different clans in terms of their castes for mutual interaction. It is interesting to note that during the British Raj in the Subcontinent all the legal and documentary transactions required declaration of caste by the person concerned thus the caste of a person served as a symbol of his or her identity and introduction. -

Fafen Election

FAFEN ELECTION . 169 NA and PA constituencies with Margin of Victory less than potentially Rejected Ballots August 3, 2018 The number of ballot papers excluded increase. In Islamabad Capital Territory, from the count in General Elections 2018 the number of ballots excluded from the surpassed the number of ballots rejected count are more than double the in General Elections 2013. Nearly 1.67 rejected ballots in the region in GE-2013. million ballots were excluded from the Around 40% increase in the number of count in GE-2018. This number may ballots excluded from the count was slightly vary after the final consolidated observed in Balochistan, 30.6 % increase result is released by the Election in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa including Commission of Pakistan (ECP) as the Federally Administered Tribal Areas ballots excluded from the count at the (FATA), 7% increase in Sindh and 6.6% polling station level by Presiding Officers increase in Punjab. are to be reviewed by the Returning The following table provides a Officers during the consolidation comparison of the number of rejected proceedings, who can either reject them National Assembly ballot papers in each or count them in favor of a candidate if province/region during each of the past excluded wrongly. four General Elections in 2002, 2008, 2013 The increase in the number of ballots and 2018. Although the rejected ballots excluded from the count was a have consistently increase over the past ubiquitous phenomenon observed in all four general elections, the increase was provinces and Islamabad Capital significantly higher in 2013 than 2008 Territory with nearly 11.7% overall (54.3%). -

Development of High Speed Rail in Pakistan

TSC-MT 11-014 Development of High Speed Rail in Pakistan Stockholm, June 2011 Master Thesis Abdul Majeed Baloch KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 2 Foreword I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Anders Lindahl, Bo-Lennart Nelldal & Oskar Fröidh for their encouragement, patience, help, support at different stages & excellent guidance with Administration, unique ideas, feedback etc. Above all I would like to thank my beloved parents ’Shazia Hassan & Dr. Ali Hassan’ , my brothers, sisters from soul of my heart, for encouragement & support to me through my stay in Sweden, I wish to say my thanks to all my friends specially ‘ Christina Nilsson’ for her encouragement, and my Landlord ‘Mikeal & Ingmarie’ in Sweden . Finally I would like to say bundle of thanks from core of my Heart to KTH , who has given me a chance for higher education & all people who has been involved directly or in-directly with completion of my thesis work Stockholm, June 2011 Abdul Majeed Baloch [email protected] KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 3 KTH |Development of High Speed Rail In Pakistan 4 Summary Passenger Railway service are one of the key part of the Pakistan Railway system. Pakistan Railway has spent handsome amount of money on the Railway infrastructure, but unfortunately tracks could not be fully utilized. Since last many years due to the fall of the Pakistan railway, road transport has taken an advantage of this & promised to revenge. Finally road transport has increased progressive amount of share in his account. In order to get the share back, in 2006 Pakistan Railway decided to introduce High speed train between Rawalpindi-Lahore 1.According Pakistan Railway year book 2010, feasibility report for the high speed train between Rawalpindi-Lahore has been completed. -

Jhang: Annual Development Program and Its Implementation (2008-09)

April 2009 CPDI District Jhang: Annual Development Program and its Implementation (2008-09) Table of Contents 1. Background 2. Annual Development Program (2008-09) 3. Implementation of Annual Development Program (2008-09): Issues and Concerns 4. Recommendations Centre for Peace and Development Initiatives (CPDI) 1 District Jhang: Annual Development Program and its Implementation (2008-09) 1. Background Jhang district is located in the Punjab province. Total area of the district is 8,809 square kilometers. It is bounded on the north by Sargodha and Hafizabad districts, on the south by Khanewal district, on the west by Layyah, Bhakkar and Khushab districts, on the east by Faisalabad and Toba Tek Singh districts and on the south-west by Muzaffargarh district. According to the census conducted in 1998, the total population of the district was 2.8 million, as compared to about 2 million in 1981. It is largerly a rural district as only around 23% people live in the urban areas. According to a 2008 estimate, the population of the district has risen to about 3.5 million. Table 1: Population Profile of Jhang District 1951 1961 1972 1981 1998 Total 8,63,000 10,65,000 15,55,000 19,71,000 28,34,545 Rural - - - - 21,71,555 Urban - - - - 6,62,990 Urban population as %age of Total - - - - 23.4% Source: Population Census Organization, Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan , District Census Report of Jhang, Islamabad, August 2000. Jhang is one of the oldest districts of the Punjab province. Currently, the district consists of 4 tehsils: Ahmad Pur Sial, Chiniot, Jhang and Shorkot. -

Special Report No

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 494 | MAY 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org The Evolution and Potential Resurgence of the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan By Amira Jadoon Contents Introduction ...................................3 The Rise and Decline of the TTP, 2007–18 .....................4 Signs of a Resurgent TPP, 2019–Early 2021 ............... 12 Regional Alliances and Rivalries ................................ 15 Conclusion: Keeping the TTP at Bay ............................. 19 A Pakistani soldier surveys what used to be the headquarters of Baitullah Mehsud, the TTP leader who was killed in March 2010. (Photo by Pir Zubair Shah/New York Times) Summary • Established in 2007, the Tehrik-i- attempts to intimidate local pop- regional affiliates of al-Qaeda and Taliban Pakistan (TTP) became ulations, and mergers with prior the Islamic State. one of Pakistan’s deadliest militant splinter groups suggest that the • Thwarting the chances of the TTP’s organizations, notorious for its bru- TTP is attempting to revive itself. revival requires a multidimensional tal attacks against civilians and the • Multiple factors may facilitate this approach that goes beyond kinetic Pakistani state. By 2015, a US drone ambition. These include the Afghan operations and renders the group’s campaign and Pakistani military Taliban’s potential political ascend- message irrelevant. Efforts need to operations had destroyed much of ency in a post–peace agreement prioritize investment in countering the TTP’s organizational coherence Afghanistan, which may enable violent extremism programs, en- and capacity. the TTP to redeploy its resources hancing the rule of law and access • While the TTP’s lethality remains within Pakistan, and the potential to essential public goods, and cre- low, a recent uptick in the number for TTP to deepen its links with ating mechanisms to address legiti- of its attacks, propaganda releases, other militant groups such as the mate grievances peacefully. -

Population Growth & Distribution Pattern in Punjab, Pakistan

Volume 3, Issue 1, January – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456 –2165 Population Growth & Distribution Pattern in Punjab, Pakistan (1998-2017): A Geospatial Approach Dr. Faiza Mazhar TTS Assistant Professor Geography Department. Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan Abstract: This study is about the population growth and B. Population Distribution in 1998 distribution pattern of Punjab, Pakistan. According the current census of 2017 the Punjab is still having largest share of population but minimum growth rate in Pakistan According to 1998 census the total number of Punjab’s as compare to other provinces. This will impact its NA population was raised to 73,621,290 from 47,292,441 of 1981 seats and other resource distribution. census. It was increased at the rate of 2-6 and it was 55.7 % share of the total population of Pakistan. In 1998 Punjab’s Keywords—Population; Growth; Distribution; Density; population density increased up to 359 persons/ sq. km. it was 230 persons per sq. kilometer in 1981. [2] I. INTRODUCTION The word Punjab means ("the land of five rivers") which refers to the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas and Sutlej Rivers, all of which are tributaries of the Indus River. This is an area in South Asia that is situated in Pakistan. According to the current census 2017, the total count of population in Pakistan is 207,774,520 as reported by census department of Pakistan. Punjab is on top of the charts with around 110 million population. Sindh has scored the second position with 47 million people. -

Punjab Health Statistics 2019-2020.Pdf

Calendar Year 2020 Punjab Health Statistics HOSPITALS, DISPENSARIES, RURAL HEALTH CENTERS, SUB-HEALTH CENTERS, BASIC HEALTH UNITS T.B CLINICS AND MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH CENTERS AS ON 01.01.2020 BUREAU OF STATISTICS PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT BOARD GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE www.bos.gop.pk Content P a g e Sr. No. T i t l e No. 1 Preface I 2 List of Acronym II 3 Introduction III 4 Data Collection System IV 5 Definitions V 6 List of Tables VI 7 List of Figures VII Preface It is a matter of pleasure, that Bureau of Statistics, Planning & Development Board, Government of the Punjab has took initiate to publish "Punjab Health Statistics 2020". This is the first edition and a valuable increase in the list of Bureau's publication. This report would be helpful to the decision makers at District/Tehsil as well as provincial level of the concern sector. The publication has been formulated on the basis of information received from Director General Health Services, Chief Executive Officers (CEO’s), Inspector General (I.G) Prison, Auqaf Department, Punjab Employees Social Security, Pakistan Railways, Director General Medical Services WAPDA, Pakistan Nursing Council and Pakistan Medical and Dental Council. To meet the data requirements for health planning, evaluation and research this publication contain detailed information on Health Statistics at the Tehsil/District/Division level regarding: I. Number of Health Institutions and their beds’ strength II. In-door & Out-door patients treated in the Health Institutions III. Registered Medical & Para-Medical Personnel It is hoped that this publication would prove a useful reference for Government departments, private institutions, academia and researchers. -

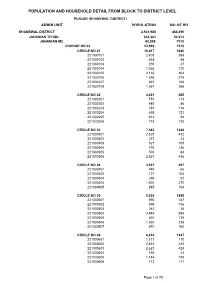

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (KHANEWAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH KHANEWAL DISTRICT 2,921,986 466,390 JAHANIAN TEHSIL 343,361 52,613 JAHANIAN MC 43,598 7010 CHARGE NO 03 43,598 7010 CIRCLE NO 01 10,417 1640 221030101 2,403 388 221030102 614 84 221030103 250 47 221030104 1,065 170 221030105 2,135 304 221030106 1,596 275 221030107 697 106 221030108 1,657 266 CIRCLE NO 02 4,001 655 221030201 751 113 221030202 480 86 221030203 781 116 221030204 658 121 221030205 613 94 221030206 718 125 CIRCLE NO 03 7,583 1226 221030301 2,625 432 221030302 237 43 221030303 521 105 221030304 776 126 221030305 503 84 221030306 2,921 436 CIRCLE NO 04 3,947 657 221030401 440 66 221030402 727 104 221030403 295 52 221030404 1,600 272 221030405 885 163 CIRCLE NO 05 9,034 1485 221030501 990 187 221030502 898 156 221030503 262 38 221030504 3,844 583 221030505 810 135 221030506 1,360 226 221030507 870 160 CIRCLE NO 06 8,616 1347 221030601 1,111 170 221030602 2,812 425 221030603 2,621 424 221030604 156 23 221030605 1,144 188 221030606 772 117 Page 1 of 74 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (KHANEWAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JAHANIAN QH 169,785 25814 055/10-R PC 5,480 875 CHAK NO 053/10-R 1,932 337 221011403 1,124 197 221011404 700 124 221011405 108 16 CHAK NO 054/10-R 2,037 318 221011402 1,133 188 221011406 904 130 CHAK NO 055/10-R 1,511 220 221011401 1,511 220 056/10-R PC 6,093 890 CHAK NO 056/10-R 2,028 307 221011501 1,059 157 221011502 969 150 CHAK NO 057/10-R 2,786 -

The Pakistan Army's Repression of the Punjab

Human Rights Watch July 2004 Vol. 16, No. 10 (C) Soiled Hands: The Pakistan Army’s Repression of the Punjab Farmers’ Movement Map 1: Pakistan – Provinces........................................................................................................ 1 Map 2: Punjab – Districts ............................................................................................................ 2 Table 1: Population Distribution across Okara District ......................................................... 3 I. Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 4 II. Key Recommendations........................................................................................................... 8 III. Background ............................................................................................................................. 9 Struggle Against Eviction ........................................................................................................ 9 “Ownership or Death”: Radicalization of the farmers’ movement ................................12 The Pakistan Rangers.............................................................................................................14 The Response of the Pakistan Army ...................................................................................17 IV. Human Rights Violations....................................................................................................19 Killings......................................................................................................................................20 -

Microbiological and Physicochemical Assessments of Groundwater Quality at Punjab, Pakistan

Vol. 8(28), pp. 2672-2681, 9 July, 2014 DOI: 10.5897/AJMR2014.6701 Article Number: 852257345925 ISSN 1996-0808 African Journal of Microbiology Research Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJMR Full Length Research Paper Microbiological and physicochemical assessments of groundwater quality at Punjab, Pakistan Ammara Hassan1* and M. Nawaz2 1Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Lahore, Pakistan. 2College of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. Received 10 February, 2014; Accepted 23 June, 2014 The assessment of groundwater is essential for the estimation of suitability of water for safe use. An attempt has been made to study the groundwater at the district level of Punjab, Pakistan. These samples were analyzed for various water quality parameters like pH, color, odor, conductance, total suspended solids, trace metals (Fe, cu, B, Ba, Al, Cr, Cd, Ni, Mn and Se), ionic concentration (HCO3, CO3, Cl, SO4, Na, K, Ca, Mg, NO3, NO2, NH4, F, PO4 and CN) and for microbiological enumeration (total viable count, total and fecal coliforms Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp. and Pseudomonas spp.). The data was analyzed with WHO guidelines/ recommendations. The results of physical analysis indicated that all samples are safe except the groundwater of Kasur and Khanewal District. About 66.67% samples are out of total suspended solids (TSS) limit. Microbiologically, only six groundwater of Punjab districts are found potable according to WHO limits. In the trace metals analysis, highest level of iron was detected in Jhang while the groundwater of three districts were not potable due to high level of boron and nickel but the groundwater of all districts was found safe with respect to Ba, Al and Cr. -

Balochistan Review” ISSN: 1810-2174 Publication Of: Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan

- I - ISSN: 1810-2174 Balochistan Review Volume XXXIV No. 1, 2016 Recognized by Higher Education Commission of Pakistan Editor: Ghulam Farooq Baloch BALOCHISTAN STUDY CENTRE UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA-PAKISTAN - II - Bi-Annual Research Journal “Balochistan Review” ISSN: 1810-2174 Publication of: Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. @ Balochistan Study Centre 2016-1 Subscription rate in Pakistan: Institutions: Rs. 300/- Individuals: Rs. 200/- For the other countries: Institutions: US$ 15 Individuals: US$ 12 For further information please Contact: Ghulam Farooq Baloch Assistant Professor & Editor: Balochistan Review Balochistan Study Centre, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Tel: (92) (081) 9211255 Facsimile: (92) (081) 9211255 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.uob.edu.pk/journals/bsc.htm No responsibility for the views expressed by authors and reviewers in Balochistan Review is assumed by the Editor, Assistant Editor and the Publisher. - III - Editorial Board Patron in Chief: Prof. Dr. Javeid Iqbal Vice Chancellor, University of Balochistan, Quetta-Pakistan. Patron Prof. Dr. Abdul Hameed Shahwani Director, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Editor Ghulam Farooq Baloch Asstt Professor, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Assistant Editor Waheed Razzaq Research Officer, Balochistan Study Centre, UoB, Quetta-Pakistan. Members: Prof. Dr. Andriano V. Rossi Vice Chancellor & Head Dept of Asian Studies, Institute of Oriental Studies, Naples, Italy. Prof. Dr. Saad Abudeyha Chairman, Dept. of Political Science, University of Jordon, Amman, Jordon. Prof. Dr. Bertrand Bellon Professor of Int’l, Industrial Organization & Technology Policy, University de Paris Sud, France. Dr. Carina Jahani Inst. of Iranian & African Studies, Uppsala University, Sweden. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Ashraf Khan Director, Taxila Institute of Asian Civilizations, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan. -

Pakistan: Country Report the Situa�On in Pakistan

Asylum Research Centre Pakistan: Country Report /shutterstock.com The situa�on in Pakistan Lukasz Stefanski June 2015 (COI up to 20 February 2015) Cover photo © 20 February 2015 (published June 2015) Pakistan Country Report Explanatory Note Sources and databases consulted List of Acronyms CONTENTS 1. Background Information 1.1. Status of tribal areas 1.1.1. Map of Pakistan 1.1.2. Status in law of the FATA and governance arrangements under the Pakistani Constitution 1.1.3. Status in law of the PATA and governance arrangements under the Pakistani Constitution 1.2. General overview of ethnic and linguistic groups 1.3. Overview of the present government structures 1.3.1. Government structures and political system 1.3.2. Overview of main political parties 1.3.3. The judicial system, including the use of tribal justice mechanisms and the application of Islamic law 1.3.4. Characteristics of the government and state institutions 1.3.4.1. Corruption 1.3.4.2. Professionalism of civil service 1.3.5. Role of the military in governance 1.4. Overview of current socio-economic issues 1.4.1. Rising food prices and food security 1.4.2. Petrol crisis and electricity shortages 1.4.3. Unemployment 2. Main Political Developments (since June 2013) 2.1. Current political landscape 2.2. Overview of major political developments since June 2013, including: 2.2.1. May 2013: General elections 2.2.2. August-December 2014: Opposition protests organised by Pakistan Tekreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT) 2.2.3. Former Prime Minister Raja Pervaiz Ashraf 2.3.