Leptospirosis Annual Report 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Can Leptospirosis Be Treated Without Any Kind of Medication?

ISSN: 2573-9565 Research Article Journal of Clinical Review & Case Reports Can Leptospirosis Be Treated Without Any Kind of Medication? Huang W L* *Corresponding author Huang Wei Ling, Rua Homero Pacheco Alves, 1929, Franca, Sao Paulo, Infectologist, general practitioner, nutrition doctor, acupuncturist, 14400-010, Brazil, Tel: (+55 16) 3721-2437; E-mail: [email protected] pain management, Medical Acupuncture and Pain Management Clinic, Franca, Sao Paulo, Brazil Submitted: 16 Apr 2018; Accepted: 23 Apr 2018; Published: 10 May 2018 Abstract Introduction: Leptospirosis is an acute infectious disease caused by pathogenic Leptospira. Spread in a variety of ways, though the digestive tract infection is the main route of infection. As the disease pathogen final position in the kidney, the urine has an important role in the proliferation of the disease spreading [1]. Purpose: The purpose of this study was to show if leptospirosis can be treated without any kind of medication. The methodology used was the presentation of one case report of a woman presenting three days of generalized pain all over her body, especially in her muscles, mainly the calves of her legs, fever, headache and trembling. A blood exam was asked, as well as serology and acupuncture to relieve her symptoms. Findings: she recovered very well after five sessions of Acupuncture once a day. A month later, she came back with the results of her serology: it was positive leptospirosis. Conclusion: In this case, leptospirosis was cured without the use any kind of medication, being acupuncture a good therapeutic option, reducing the necessity of the patient’s admittance into a hospital, minimizing the costs of the treatmentand restoring the patient to a normal life very quickly. -

Leptospirosis Associated Equine Recurrent Uveitis Answers to Your Important Questions What Is Leptospirosis Associated Equine Recurrent Uveitis (LAERU)?

Lisa Dauten, DVM Tri-State Veterinary Services LLC " Leptospirosis Associated Equine Recurrent Uveitis Answers to your Important Questions! What is Leptospirosis Associated Equine Recurrent Uveitis (LAERU)? Let’s start by breaking down some terminology.! Uveitis- inflammation of the uvea. Resulting in cloudiness of the eye, pain, and potential blindness. Also know as “Moon Blindness”. Caused by trauma, infection, or corneal disease.! Uvea- part of the eye containing the iris, ciliary body, and choroid. It keeps the lens of the eye in place, maintains fluid in the eye, and keeps things in the blood from entering the inside of the eye (blood-ocular barrier). ! Recurrent Uveitis- inflammation of the uvea that sporadically reoccurs through out a horses life time. Each time there is a reoccurring episode, the damage to the eye is made worse, eventually leading to permanent damage and potential blindness. ! Leptospirosis- bacteria found in the environment shed in the urine of wildlife and livestock. Horses usually are exposed when grazing pastures or drinking from natural water sources.! LAERU- Recurrent Uveitis in horses caused by Leptospirosis.! What are the clinical signs of Uveitis? Uveitis can come on very suddenly. A lot of times horses present with severe pain in the eye, tearing, squinting, and rubbing face. The eye itself is cloudy, white or blue in color. Sometimes the signs are not as dramatic. The color change of the eye may progress slowly. In these cases, horse owners may mistake the changes for cataracts.! What do I do if I think my horse has Uveitis? Call your veterinarian to request an appointment. -

Leptospirosis: a Waterborne Zoonotic Disease of Global Importance

August 2006 volume 22 number 08 Leptospirosis: A waterborne zoonotic disease of global importance INTRODUCTION syndrome has two phases: a septicemic and an immune phase (Levett, 2005). Leptospirosis is considered one of the most common zoonotic diseases It is in the immune phase that organ-specific damage and more severe illness globally. In the United States, outbreaks are increasingly being reported is seen. See text box for more information on the two phases. The typical among those participating in recreational water activities (Centers for Disease presenting signs of leptospirosis in humans are fever, headache, chills, con- Control and Prevention [CDC], 1996, 1998, and 2001) and sporadic cases are junctival suffusion, and myalgia (particularly in calf and lumbar areas) often underdiagnosed. With the onset of warm temperatures, increased (Heymann, 2004). Less common signs include a biphasic fever, meningitis, outdoor activities, and travel, Georgia may expect to see more leptospirosis photosensitivity, rash, and hepatic or renal failure. cases. DIAGNOSIS OF LEPTOSPIROSIS Leptospirosis is a zoonosis caused by infection with the bacterium Leptospira Detecting serum antibodies against leptospira interrogans. The disease occurs worldwide, but it is most common in temper- • Microscopic Agglutination Titers (MAT) ate regions in the late summer and early fall and in tropical regions during o Paired serum samples which show a four-fold rise in rainy seasons. It is not surprising that Hawaii has the highest incidence of titer confirm the diagnosis; a single high titer in a per- leptospirosis in the United States (Levett, 2005). The reservoir of pathogenic son clinically suspected to have leptospirosis is highly leptospires is the renal tubules of wild and domestic animals. -

Leptospirosis and Coinfection: Should We Be Concerned?

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Leptospirosis and Coinfection: Should We Be Concerned? Asmalia Md-Lasim 1,2, Farah Shafawati Mohd-Taib 1,* , Mardani Abdul-Halim 3 , Ahmad Mohiddin Mohd-Ngesom 4 , Sheila Nathan 1 and Shukor Md-Nor 1 1 Department of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, UKM, Bangi 43600, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] (A.M.-L.); [email protected] (S.N.); [email protected] (S.M.-N.) 2 Herbal Medicine Research Centre (HMRC), Institute for Medical Research (IMR), National Institue of Health (NIH), Ministry of Health, Shah Alam 40170, Selangor, Malaysia 3 Biotechnology Research Institute, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, Kota Kinabalu 88400, Sabah, Malaysia; [email protected] 4 Center for Toxicology and Health Risk, Faculty of Health Sciences, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur 50300, Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +60-12-3807701 Abstract: Pathogenic Leptospira is the causative agent of leptospirosis, an emerging zoonotic disease affecting animals and humans worldwide. The risk of host infection following interaction with environmental sources depends on the ability of Leptospira to persist, survive, and infect the new host to continue the transmission chain. Leptospira may coexist with other pathogens, thus providing a suitable condition for the development of other pathogens, resulting in multi-pathogen infection in humans. Therefore, it is important to better understand the dynamics of transmission by these pathogens. We conducted Boolean searches of several databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Citation: Md-Lasim, A.; Mohd-Taib, SciELO, and ScienceDirect, to identify relevant published data on Leptospira and coinfection with F.S.; Abdul-Halim, M.; Mohd-Ngesom, other pathogenic bacteria. -

Ehrlichiosis in Brazil

Review Article Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet., Jaboticabal, v. 20, n. 1, p. 1-12, jan.-mar. 2011 ISSN 0103-846X (impresso) / ISSN 1984-2961 (eletrônico) Ehrlichiosis in Brazil Erliquiose no Brasil Rafael Felipe da Costa Vieira1; Alexander Welker Biondo2,3; Ana Marcia Sá Guimarães4; Andrea Pires dos Santos4; Rodrigo Pires dos Santos5; Leonardo Hermes Dutra1; Pedro Paulo Vissotto de Paiva Diniz6; Helio Autran de Morais7; Joanne Belle Messick4; Marcelo Bahia Labruna8; Odilon Vidotto1* 1Departamento de Medicina Veterinária Preventiva, Universidade Estadual de Londrina – UEL 2Departamento de Medicina Veterinária, Universidade Federal do Paraná – UFPR 3Department of Veterinary Pathobiology, University of Illinois 4Department of Veterinary Comparative Pathobiology, Purdue University, Lafayette 5Seção de Doenças Infecciosas, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul – UFRGS 6College of Veterinary Medicine, Western University of Health Sciences 7Department of Clinical Sciences, Oregon State University 8Departamento de Medicina Veterinária Preventiva e Saúde Animal, Universidade de São Paulo – USP Received June 21, 2010 Accepted November 3, 2010 Abstract Ehrlichiosis is a disease caused by rickettsial organisms belonging to the genus Ehrlichia. In Brazil, molecular and serological studies have evaluated the occurrence of Ehrlichia species in dogs, cats, wild animals and humans. Ehrlichia canis is the main species found in dogs in Brazil, although E. ewingii infection has been recently suspected in five dogs. Ehrlichia chaffeensis DNA has been detected and characterized in mash deer, whereas E. muris and E. ruminantium have not yet been identified in Brazil. Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis caused by E. canis appears to be highly endemic in several regions of Brazil, however prevalence data are not available for several regions. -

Diseases of Wisconsin Furbearers

Tularemia Non-Zoonotic Diseases of Tyzzer’s Disease (Francisella tularensis) (Clostridium piliforme) Diseases of Tularemia is also known as “rabbit fever.” This bacterial Wisconsin Furbearers Tyzzer’s disease is a bacterial infection that is seen in disease is most frequently found in Wisconsin rabbits, muskrats and cottontail rabbits. It is not a disease risk muskrat, or beaver. An infected animal will generally be Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) for humans. Animals are usually found dead in good Wisconsin in good physical condition, but have an enlarged spleen Canine distemper virus affects mainly raccoon and gray physical condition, as animals can get sick and die within or liver covered with small white spots. fox populations, but can also infect other carnivores. a few hours after infection. Overpopulation, limited Furbearers CDV can be transmitted to domestic dogs, but is not a food resources, and other stress factors may contribute to Since this disease can be transmitted to humans, risk to humans. Infected animals appear lethargic and outbreaks of this disease. Animals with Tyzzer’s disease trappers should take precautions. Always wear gloves may show no fear of humans, wander aimlessly, have have blood engorged organs, but only laboratory testing when skinning or processing these animals. The most respiratory signs, discharge from the eyes, or nervous can confirm this infection. Signs of Tyzzer’s disease common symptoms for humans are a slow-healing skin system signs such as convulsions and chewing fits. mimic those of tularemia, so it is important to confirm sore or ulcer and swollen lymph nodes. Less frequently, Contact a Wildlife Biologist if you see signs of CDV as which disease is affecting the furbearer. -

Outbreak of Melioidosis and Leptospirosis Co-Infection Following a Rescue Operation

10-Outbreak_3-PRIMARY.qxd 7/10/12 5:15 PM Page 293 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Outbreak of Melioidosis and Leptospirosis Co-infection Following a Rescue Operation M Sapian 1, M T Khairi 2, S H How 3, R Rajalingam 4, K Sahhir 5, A Norazah 6, V Khebir 7, A R Jamalludin 8 1 Pahang State Health Department, 2 Jengka Health Clinic, 3 International Islamic University Malaysia, 4 Hospital Sultan Haji Ahmad Shah, Temerloh, 5 Pahang State Health Department, 6 Institute of Medical Research, Kuala Lumpur, 7 Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia, 8 International Islamic University Malaysia SUMMARY entry of the organism into the blood stream via very minor We analyzed the epidemiological data of all people who wounds or skin abrasions. Person with underlying diseases were involved in the search and rescue operation in Lubuk especially diabetes mellitus are more likely to develop Yu, a natural recreational forest with waterfall and stream. melioidosis (20-74% of cases) 1-5,7,8 . The hospital admission records of the cases who fulfilled the case definition and the environmental samples result taken Leptospirosis is an infectious disease that affects humans and at Lubuk Yu recreational area were studied. 153 people were animals. It is considered the most common zoonotic disease exposed to this outbreak, 85 (55.5%) were professional in the world 9,10 . Leptospirosis is caused by pathogenic spiral rescuers from various government agencies and 68 (44.5%) bacteria that belong to the genus Leptospira 11,12 . The organism were villagers. 21 fulfilled the case definition. Ten cases were enters the body when mucous membranes or abraded skin confirmed melioidosis, six melioidosis alone and four co- come in contact with contaminated environmental sources 13 . -

Tularemia (CFSPH)

Tularemia Importance Tularemia is a zoonotic bacterial disease with a wide host range. Infections are most prevalent among wild mammals and marsupials, with periodic epizootics in Rabbit Fever, lagomorphs and rodents, but clinical cases also occur in sheep, cats and other Deerfly Fever, domesticated species. A variety of syndromes can be seen, but fatal septicemia is Meat-Cutter’s Disease common in some species. In humans, tularemia varies from a localized infection to Ohara Disease, fulminant, life-threatening pneumonia or septicemia. Francis Disease Tularemia is mainly seen in the Northern Hemisphere, where it has recently emerged or re-emerged in some areas, including parts of Europe and the Middle East. A few endemic clinical cases have also been recognized in regions where this disease Last Updated: June 2017 was not thought to exist, such as Australia, South Korea and southern Sudan. In some cases, emergence may be due to increased awareness, surveillance and/or reporting requirements; in others, it has been associated with population explosions of animal reservoir hosts, or with social upheavals such as wars, where sanitation is difficult and infected rodents may contaminate food and water supplies. Occasionally, this disease may even be imported into a country in animals. In 2002, tularemia entered the Czech Republic in a shipment of sick pet prairie dogs from the U.S. Etiology Tularemia is caused by Francisella tularensis (formerly known as Pasteurella tularensis), a Gram negative coccobacillus in the family Francisellaceae and class γ- Proteobacteria. Depending on the author, either three or four subspecies are currently recognized. F. tularensis subsp. tularensis (also known as type A) and F. -

Tularemia – Epidemiology

This first edition of theWHO guidelines on tularaemia is the WHO GUIDELINES ON TULARAEMIA result of an international collaboration, initiated at a WHO meeting WHO GUIDELINES ON in Bath, UK in 2003. The target audience includes clinicians, laboratory personnel, public health workers, veterinarians, and any other person with an interest in zoonoses. Tularaemia Tularaemia is a bacterial zoonotic disease of the northern hemisphere. The bacterium (Francisella tularensis) is highly virulent for humans and a range of animals such as rodents, hares and rabbits. Humans can infect themselves by direct contact with infected animals, by arthropod bites, by ingestion of contaminated water or food, or by inhalation of infective aerosols. There is no human-to-human transmission. In addition to its natural occurrence, F. tularensis evokes great concern as a potential bioterrorism agent. F. tularensis subspecies tularensis is one of the most infectious pathogens known in human medicine. In order to avoid laboratory-associated infection, safety measures are needed and consequently, clinical laboratories do not generally accept specimens for culture. However, since clinical management of cases depends on early recognition, there is an urgent need for diagnostic services. The book provides background information on the disease, describes the current best practices for its diagnosis and treatment in humans, suggests measures to be taken in case of epidemics and provides guidance on how to handle F. tularensis in the laboratory. ISBN 978 92 4 154737 6 WHO EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO Guidelines on Tularaemia EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data WHO Guidelines on Tularaemia. -

1 Global Burden of Melioidosis, 2015: a Systematic Review and Data Synthesis Emma Birnie, MD1*, Harjeet S. Virk, MD1*,Jelmer Sa

Global burden of melioidosis, 2015: a systematic review and data synthesis Emma Birnie, MD1*, Harjeet S. Virk, MD1*, Jelmer Savelkoel, BSc1, Rene Spijker, MsC2 Eric Bertherat, MD3, David A.B. Dance, Prof, FRCPath4,5,6, Direk Limmathurotsakul, PhD5,7, Brecht Devleesschauwer, PhD8,9, Juanita A. Haagsma, PhD10, W. Joost Wiersinga, Prof, PhD1,11 *Authors contributed equally to the manuscript 1 Center for Experimental and Molecular Medicine, Amsterdam UMC, location AMC, Amsterdam Infection & Immunity Institute, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 2 Cochrane Netherlands, Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, University Utrecht, the Netherlands and Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Medical Library, Amsterdam Public Health, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 3 Department of Infectious Hazard Management, Health Emergency programme, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; 4 Lao-Oxford-Mahosot Hospital-Wellcome Trust Research Unit, Microbiology Laboratory, Mahosot Hospital, Vientiane, Lao PDR; 5 Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK; 6 Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK; 7 Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; 8 Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, Sciensano, Brussels, Belgium; 9 Department of Veterinary Public Health and Food Safety, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent University, Merelbeke, Belgium 10 Department -

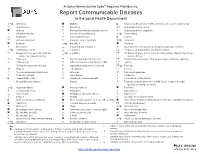

Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department

Arizona Administrative Code Requires Providers to: Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department *O Amebiasis Glanders O Respiratory disease in a health care institution or correctional facility Anaplasmosis Gonorrhea * Rubella (German measles) Anthrax Haemophilus influenzae, invasive disease Rubella syndrome, congenital Arboviral infection Hansen’s disease (Leprosy) *O Salmonellosis Babesiosis Hantavirus infection O Scabies Basidiobolomycosis Hemolytic uremic syndrome *O Shigellosis Botulism *O Hepatitis A Smallpox Brucellosis Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Spotted fever rickettsiosis (e.g., Rocky Mountain spotted fever) *O Campylobacteriosis Hepatitis C Streptococcal group A infection, invasive disease Chagas infection and related disease *O Hepatitis E Streptococcal group B infection in an infant younger than 90 days of age, (American trypanosomiasis) invasive disease Chancroid HIV infection and related disease Streptococcus pneumoniae infection (pneumococcal invasive disease) Chikungunya Influenza-associated mortality in a child 1 Syphilis Chlamydia trachomatis infection Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ disease) *O Taeniasis * Cholera Leptospirosis Tetanus Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) Listeriosis Toxic shock syndrome Colorado tick fever Lyme disease Trichinosis O Conjunctivitis, acute Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Tuberculosis, active disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Malaria Tuberculosis latent infection in a child 5 years of age or younger (positive screening test result) *O Cryptosporidiosis -

Leptospirosis Signs and • May Be Asymptomatic, May Be Biphasic

Leptospirosis Signs and • May be asymptomatic, may be biphasic. Severe muscle aches (calves and lumbar Symptoms region) and conjunctival suffusion are specific findings but less common. • Acute phase: fever begins abruptly, chills, headaches, muscle aches, cough, vomiting, diarrhea, jaundice, or rash. • Convalescent phase (~10%): More severe, with possible kidney or liver failure, meningitis, respiratory distress, bleeding. 5-15% case fatality if severe. Incubation 5-14 days (range 2-30 days) Case Clinical criteria: Fever within the past two weeks and at least two of the following classification clinical findings: myalgia, headache, jaundice, conjunctival suffusion without purulent discharge, or rash (i.e., maculopapular or petechial); OR at least one of the following clinical findings: aseptic meningitis, GI symptoms (e.g., abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), pulmonary complications (e.g., cough, breathlessness, hemoptysis), cardiac arrhythmias, ECG abnormalities, renal insufficiency (e.g., anuria, oliguria), hemorrhage (e.g., intestinal, pulmonary, hematuria, hematemesis), or jaundice with acute renal failure. Confirmed: A case with Probable: A clinically compatible case with involvement confirmed laboratory in an exposure event (e.g., adventure race, triathlon, results. flooding) with known associated cases, or any presumptive but not confirmed laboratory finding. Differential Mononucleosis, influenza, hepatitis B and C, meningitis, brucellosis, tularemia, diagnosis dengue, TBRF, Colorado tick fever, plague, rickettsiosis, ehrlichiosis, and Q fever. Treatment Antibiotic therapy, generally doxycycline or penicillin. Could become more severe if untreated, eventually requiring intravenous antibiotics. Duration Acute: 5-7 days. Convalescent: 4-30 days, beginning 3-4 days after acute phase. Exposure Broken skin or mucous exposure to urine or tissues from infected animals or contact with water or soil contaminated with urine of infected animals.