Concerns with the Southwest Ring Road Elbow River Crossing Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Trip Guide Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges

1 Field Trip Guide Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges, Foothills, and Great Plains Canadian Society of Soil Science Annual Meeting, Banff, Alberta May 2014 Field trip leaders: Dan Pennock (U. of Saskatchewan) and Paul Sanborn (U. Northern British Columbia) Field Guide Compiled by: Dan and Lea Pennock This Guidebook could be referenced as: Pennock D. and L. Pennock. 2014. Soils and Landscapes of the Front Ranges, Foothills, and Great Plains. Field Trip Guide. Canadian Society of Soil Science Annual Meeting, Banff, Alberta May 2014. 18 p. 2 3 Banff Park In the fall of 1883, three Canadian Pacific Railway construction workers stumbled across a cave containing hot springs on the eastern slopes of Alberta's Rocky Mountains. From that humble beginning was born Banff National Park, Canada's first national park and the world's third. Spanning 6,641 square kilometres (2,564 square miles) of valleys, mountains, glaciers, forests, meadows and rivers, Banff National Park is one of the world's premier destination spots. In Banff’s early years, The Canadian Pacific Railway built the Banff Springs Hotel and Chateau Lake Louise, and attracted tourists through extensive advertising. In the early 20th century, roads were built in Banff, at times by war internees, and through Great Depression-era public works projects. Since the 1960s, park accommodations have been open all year, with annual tourism visits to Banff increasing to over 5 million in the 1990s. Millions more pass through the park on the Trans-Canada Highway. As Banff is one of the world's most visited national parks, the health of its ecosystem has been threatened. -

![New York State Petroleum Business Tax Druwbcamcw^]B M]Q >WPR]Brb](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3637/new-york-state-petroleum-business-tax-druwbcamcw-b-m-q-wpr-brb-113637.webp)

New York State Petroleum Business Tax Druwbcamcw^]B M]Q >WPR]Brb

Publication 532 New York State Petroleum Business Tax DRUWbcaMcW^]bM]Q>WPR]bRb NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TAXATION AND FINANCE PETROLEUM BUSINESS TAX - PUBLICATION 532 PAGE NO. 1 ISSUE DATE 08/09/2021 REGISTRATIONS CANCELLED AND SURRENDERED 02/2021 THRU 08/2021 ALL ASSERTIONS OF RE-INSTATEMENTS OF ANY REGISTRATIONS WHICH HAVE BEEN LISTED AS CANCELLED OR SURRENDERED MUST BE VERIFIED WITH THE TAX DEPARTMENT. ACCORDINGLY, IF ANY DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED TO YOU INDICATING THAT A REGISTRATION HAS BEEN RE-INSTATED, YOU SHOULD CONTACT THE DEPARTMENT'S REGISTRATION AND BOND UNIT AT (518) 591-3089 TO VERIFY THE AUTHENTICITY OF SUCH DOCUMENT. CANCEL COMMERCIAL AVIATION FUEL BUSINESS = A KERO-JET DISTRIBUTOR ONLY = K RETAILER NON-HIGHWAY DIESEL ONLY = R GRID: DIESEL FUEL DISTRIBUTOR = D RESIDUAL PRODUCTS BUSINESS = L TERMINAL OPERATOR = T DIRECT PAY PERMIT - DYED DIESEL = F MOTOR FUEL DISTRIBUTOR = M UTILITIES = U AVIATION GAS RETAIL = G NATURAL GAS = N MCTD MOTOR FUEL WHOLESALERS = W IMPORTING TRANSPORTER = I LIQUID PROPANE = P CANCELLED CANCELLED SURRENDER SURRENDER LEGAL NAME D/B/A NAME CITY ST EIN/TAX ID DATE GRID 37TH AVENUE TRUCKING INC. CORONA NY 113625758 07/15/2021 R ALCUS FUEL OIL, INC. MORICHES NY 113083439 07/15/2021 R ALPINE FUEL INC. EAST ISLIP NY 113180819 07/15/2021 R AMIGOS OIL COMPANY, INC. GREENLAWN NY 274467335 07/15/2021 R ATTIS ETHANOL FULTON, LLC ALPHARETTA GA 832710677 07/26/2021 M T BLY ENERGY SERVICE LLC PETERSBURG NY 811464155 02/21/2021 R BUTTON OIL COMPANY INC MOUNTAIN TOP PA 231654350 02/26/2021 D CRANER OIL COMPANY, INC. -

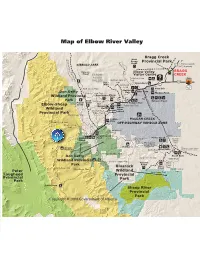

Map of Elbow River Valley

Map of Elbow River Valley ( Bragg Creek T r P a West v o e T l Bragg w Provincial Park n o o d m Creek t to Trans-Canada r e 22 e SIBBALD AREA c S r o n (#1) Highway f o m a w m c e e T n d rail e Trail BRAGG d Canyon Elbow Valley i n Creek w ELBOW Visitor Centre CREEK e t (road) w e a RIVER 758 t Fullerton Loop h e r Sulphur Springs ) VALLEY Trail Ing's Trail 22 Gooseberry 66 Mine Diamond T 40 Loop Ford Creek Trail Allen Bill Station Don Getty Flats River Cove Prairie Creek Trail McLean Pond Powderface Elbow Groups Wildland Provincial Falls Year Winter Round Gate M Gate Winter c Park Trail Gate Groups L McLean Creek Prairie Link e a Prairie Creek Paddy's Flat n Trail C Creek r Elbow-Sheep Winter Gate e Riverview Trail e Beaver k Elbow R Flat o Wildland River a Powderface BeaverLaunch d Provincial Park Ridge Trail 66 Lodge Ford Creek Trail d a o Cobble McLEAN CREEK R Flats s l Nihahi Creek Trail l a F OFF-HIGHWAY VEHICLE ZONE Nihahi Ridge ow lb N TTrail E Wildhorse Trail Winter Forgetmenot Gate Pond Fisher Creek Little Hog's Back Curley Elbow Trail Sands Threepoint Trail Creek Trail Wildhorse to Mount Groups Millarville, Turner Valley, Romulus North ForkMesa Butte Black Diamond, Calgary Winter Trail Gate Threepoint Mtn. Trail 549 Don Getty North Fork Gorge Creek Trail Big 9999 Trail Wildland Provincial Elbow Volcano Ridge Trail Volcano Ware Park Ridge Creek Bluerock Ware Little Elbow Trail Creek Trail Big Elbow Trail Wildland Death Valley Peter Link Creek Trail Trail Lougheed Provincial Provincial Park Park Tombstone Sheep River Provincial Park Copyright © 2008 Government of Alberta. -

Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta

Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Submitted to: Submitted by: SSRB Water Storage Opportunities AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Steering Committee a Division of AMEC Americas Limited Lethbridge, Alberta Lethbridge, Alberta 2014 amec.com WATER STORAGE OPPORTUNITIES IN THE SOUTH SASKATCHEWAN RIVER BASIN IN ALBERTA Submitted to: SSRB Water Storage Opportunities Steering Committee Lethbridge, Alberta Submitted by: AMEC Environment & Infrastructure Lethbridge, Alberta July 2014 CW2154 SSRB Water Storage Opportunities Steering Committee Water Storage Opportunities in the South Saskatchewan River Basin Lethbridge, Alberta July 2014 Executive Summary Water supply in the South Saskatchewan River Basin (SSRB) in Alberta is naturally subject to highly variable flows. Capture and controlled release of surface water runoff is critical in the management of the available water supply. In addition to supply constraints, expanding population, accelerating economic growth and climate change impacts add additional challenges to managing our limited water supply. The South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Water Supply Study (AMEC, 2009) identified re-management of existing reservoirs and the development of additional water storage sites as potential solutions to reduce the risk of water shortages for junior license holders and the aquatic environment. Modelling done as part of that study indicated that surplus water may be available and storage development may reduce deficits. This study is a follow up on the major conclusions of the South Saskatchewan River Basin in Alberta Water Supply Study (AMEC, 2009). It addresses the provincial Water for Life goal of “reliable, quality water supplies for a sustainable economy” while respecting interprovincial and international apportionment agreements and other legislative requirements. -

Bow River Basin State of the Watershed Summary 2010 Bow River Basin Council Calgary Water Centre Mail Code #333 P.O

30% SW-COC-002397 Bow River Basin State of the Watershed Summary 2010 Bow River Basin Council Calgary Water Centre Mail Code #333 P.O. Box 2100 Station M Calgary, AB Canada T2P 2M5 Street Address: 625 - 25th Ave S.E. Bow River Basin Council Mark Bennett, B.Sc., MPA Executive Director tel: 403.268.4596 fax: 403.254.6931 email: [email protected] Mike Murray, B.Sc. Program Manager tel: 403.268.4597 fax: 403.268.6931 email: [email protected] www.brbc.ab.ca Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 Overview 4 Basin History 6 What is a Watershed? 7 Flora and Fauna 10 State of the Watershed OUR SUB-BASINS 12 Upper Bow River 14 Kananaskis River 16 Ghost River 18 Seebe to Bearspaw 20 Jumpingpound Creek 22 Bearspaw to WID 24 Elbow River 26 Nose Creek 28 WID to Highwood 30 Fish Creek 32 Highwood to Carseland 34 Highwood River 36 Sheep River 38 Carseland to Bassano 40 Bassano to Oldman River CONCLUSION 42 Summary 44 Acknowledgements 1 Overview WELCOME! This State of the Watershed: Summary Booklet OVERVIEW OF THE BOW RIVER BASIN LET’S TAKE A CLOSER LOOK... THE WATER TOWERS was created by the Bow River Basin Council as a companion to The mountainous headwaters of the Bow our new Web-based State of the Watershed (WSOW) tool. This Comprising about 25,000 square kilometres, the Bow River basin The Bow River is approximately 645 kilometres in length. It begins at Bow Lake, at an River basin are often described as the booklet and the WSOW tool is intended to help water managers covers more than 4% of Alberta, and about 23% of the South elevation of 1,920 metres above sea level, then drops 1,180 metres before joining with the water towers of the watershed. -

Monitoring the Elbow River

Freshwater Monitoring: A Case Study An educational field study for Grade 8 and 9 students Fall 2010 Acknowledgements The development of this field study program was made possible through a partnership between Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation, the Friends of Kananaskis Country, and the Elbow River Watershed Partnership. The program was written and compiled by the Environmental Education Program in Kananaskis Country and the field study equipment and programming staff were made possible through the Friends of Kananaskis Country with financial support from the Elbow River Watershed Partnership, Alberta Ecotrust, the City of Calgary, and Lafarge Canada. The Elbow River Watershed Partnership also provided technical support and expertise. These materials are copyrighted and are the property of Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation. They have been developed for educational purposes. Reproduction of student worksheets by school and other non-profit organizations is encouraged with acknowledgement of source when they are used in conjunction with this field study program. Otherwise, written permission is required for the reproduction or use of anything contained in this document. For further information contact the Environmental Education Program in Kananaskis Country. Committee responsible for implementing the program includes: Monique Dietrich Elbow River Watershed Partnership, Calgary, Alberta Jennifer Janzen Springbank High School, Springbank, Alberta Mike Tyler Woodman Junior High School, Calgary, Alberta Janice Poleschuk St. Jean Brebeuf -

South Saskatchewan River Basin Adaptation to Climate Variability Project

South Saskatchewan River Basin Adaptation to Climate Variability Project Climate Variability and Change in the Bow River Basin Final Report June 2013 This study was commissioned for discussion purposes only and does not necessarily reflect the official position of the Climate Change Emissions Management Corporation, which is funding the South Saskatchewan River Basin Adaptation to Climate Variability Project. The report is published jointly by Alberta Innovates – Energy and Environment Solutions and WaterSMART Solutions Ltd. This report is available and may be freely downloaded from the Alberta WaterPortal website at www.albertawater.com. Disclaimer Information in this report is provided solely for the user’s information and, while thought to be accurate, is provided strictly “as is” and without warranty of any kind. The Crown, its agents, employees or contractors will not be liable to you for any damages, direct or indirect, or lost profits arising out of your use of information provided in this report. Alberta Innovates – Energy and Environment Solutions (AI-EES) and Her Majesty the Queen in right of Alberta make no warranty, express or implied, nor assume any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information contained in this publication, nor that use thereof infringe on privately owned rights. The views and opinions of the author expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of AI-EES or Her Majesty the Queen in right of Alberta. The directors, officers, employees, agents and consultants of AI-EES and the Government of Alberta are exempted, excluded and absolved from all liability for damage or injury, howsoever caused, to any person in connection with or arising out of the use by that person for any purpose of this publication or its contents. -

The 2013 Flood Event in the Bow and Oldman River Basins; Causes, Assessment, and Damages

The 2013 flood event in the Bow and Oldman River basins; causes, assessment, and damages John Pomeroy1, Ronald E. Stewart2, and Paul H. Whitfield1,3,4 1Centre for Hydrology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, S7N 5C8. Phone: (306) 966-1426, Email: [email protected] 2Department of Environment and Geography, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2N2 3Department of Earth Science, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, V5A 1S6 4Environment Canada, Vancouver, BC, V6C 3S5 Event summary In late June 2013, heavy rainfall and rapidly melting alpine snow triggered flooding throughout much of the southern half of Alberta. Heavy rainfall commenced on June 19th and continued for three days. When the event was over, more than 200 mm and as much as 350 mm of precipitation fell over the Front Ranges of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Tributaries to the Bow River including the Ghost, Kananaskis, Elbow, Sheep, Highwood, and many of their tributaries all reached flood levels. The storm had a large spatial extent causing flooding to the north and south in the Red Deer and Oldman Basins, and also to the west in the Elk River in British Columbia. Convergence of the nearly synchronous floodwaters downstream in the Saskatchewan River system caused record high releases from Lake Diefenbaker through Gardiner Dam. Dam releases in Alberta and Saskatchewan attenuated the downstream flood peak such that only moderate flooding occurred in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. More than a dozen municipalities declared local states of emergency; numerous communities were placed under evacuation order in Alberta and Saskatchewan. More than 100,000 people needed to evacuate their homes, and five people died. -

Elbow River Historical Detention and Diversion Sites (Watersmart)

Elbow River Historical Detention and Diversion Sites January 2014 Submitted by: Submitted to: P. Kim Sturgess, P.Eng., FCAE Andre Corbould CEO Chief Assistant Deputy Minister WaterSMART Solutions Ltd. Alberta Flood Recovery Task Force #200, 3512 - 33 Street NW Government of Alberta Calgary, Alberta T2L 2A6 205 J.G. O’Donoghue Building 7000 – 113 Street Edmonton Alberta T6H 5T6 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 4 1. Historical Review .......................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Calgary Irrigation Company ............................................................................................5 1.1.1 Pirmez Diversion ................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Department of Interior ...................................................................................................6 1.2.1 Department of Interior Storage Sites on the Elbow River .................................................. 7 1.2.2 Department of Interior Storage Sites on Fish Creek .......................................................... 8 1.2.3 Priddis Creek Diversion ....................................................................................................... 8 1.3 The 1979 Elbow River Flood Study ...............................................................................11 1.4 The 1986 Elbow River -

Aquatic Ecosystems: the Elbow River an Educational Field Study for Biology-20 Students Acknowledgements

Aquatic Ecosystems: The Elbow River An Educational Field Study for Biology-20 Students Acknowledgements The development of this field study program was made possible through a partnership between Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation, the Friends of Kananaskis Country, and the Elbow River Watershed Partnership. The program was written and compiled by the Environmental Education Program in Kananaskis Country and the field study equipment and programming staff were made possible through the Friends of Kananaskis Country with financial support from the Elbow River Watershed Partnership, Alberta Ecotrust, the City of Calgary, and Lafarge Canada. The Elbow River Watershed Partnership also provided technical support and expertise. These materials are copyrighted and are the property of Alberta Tourism, Parks and Recreation. They have been developed for educational purposes. Reproduction of student handouts by school and other non-profit organizations is encouraged with acknowledgement of their sources when they are used in conjunction with this field study program. Otherwise, written permission is required for the reproduction or use of anything contained in this document. For further information contact the Environmental Education Program in Kananaskis Country. Committee responsible for implementing the program include: Monique Dietrich Elbow River Watershed Partnership, Calgary, Alberta Jennifer Janzen Springbank High School, Springbank, Alberta Mike Tyler Woodman Junior High School, Calgary, Alberta Janice Poleschuk St. Jean Brebeuf Junior -

Calgary's Water Supply

3/20/2021 Calgary's water supply Caution | State of local emergency renewed until May 24, 2021 Get Coronavirus (COVID-19) updates and information on closures, cancellations and service changes. Coronavirus (COVID-19) updates View our closures and service changes Calgary's water supply Where does our water come from? Print guide for Calgary's watershed Our water comes from the Rocky Mountains west of the city from a basin-like landform called a watershed. See our Homeowner Water Guide for Calgary's watershed. It is water collected from rain fall and snow melt which channels through creeks and streams making its way into larger rivers. Translations Are you a student? Find more water facts and information about Calgary's water Arabic systems at Water Education Resources. Chinese - Simplied Chinese - Traditional Hindi How the City of Calgary protects our water supply Punjabi Urdu Water is a limited resource and our water supply is changing due to climate change and a growing population. Find out how we're protecting our source water and what actions we're taking to ensure we have reliable water supply for generations to come. The Elbow River Watershed The Elbow River is the source for approximately 40 per cent of Calgary's water supply. The Elbow Valley watershed covers an area of 1,227 square kilometres and drains into the Glenmore Reservoir. It is 120 kilometres long and passes through four sub-climates before it enters the Glenmore Reservoir. The Elbow River is the source of water for the Glenmore Water Treatment Plant. We draw water from the Glenmore Reservoir in order to provide treated water to citizens, but we also play an important role in ood control for this region. -

7 Day Alberta Adventurer

Tour Code 7DAA 7 Day Alberta Adventurer 7 days Created on: 27 Sep, 2021 Day 1: Arrive Calgary Welcome to Calgary, the largest city in the western Canadian province of Alberta. While you are here to experience the bucket list adventure experience of travelling through the breath-taking Canadian Rockies, take some time to explore the award-winning architectural masterpiece of Calgary?s Public Library, walk along the scenic Bow Valley River pathways or experience the buzz of downtown Stephen Avenue with its stores and restaurants. Calgary?s dining scene is incredibly diverse and absolutely the best in western Canada. Pick up your car rental which includes unlimited km, LDW insurance and third party liability. Overnight: Calgary Day 2: Calgary - Canmore - Banff Drive to Canmore for your first day of excitement. Begin your adventure day with a magical 2 hour guided trail ride along the Bow, Kananaskis or Elbow River Valleys, with the backdrop of the Rockies. Enjoy a delicious barbecue lunch overlooking the scenic river landscape! After lunch participants meet for an exciting afternoon for your rafting adventure. Spend 2-2.5 hours on the river surfing, splashing, playing games with water canons and paddling through the rapids on a professionally guided raft. After your adventures, continue on to Banff and check in your accommodation for 2 nights. The town of Banff is a spirited place and you are surrounded by strikingly beautiful and rugged mountains that seem to burst straight out of the ground. The town site of Banff covers almost 4 sq. kms. and is at an elevation of 1,383 mtrs (4,537 feet), making it the highest town in Canada.