Meaning of SNS's to Gay Men from Non-Accepting Families

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

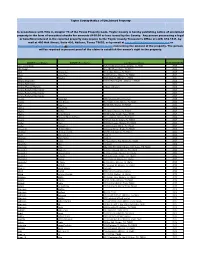

Taylor County Notice of Unclaimed Property in Accordance with Title 6

Taylor County Notice of Unclaimed Property In accordance with Title 6, Chapter 76 of the Texas Property Code, Taylor County is hereby publishing notice of unclaimed property in the form of uncashed checks for amounts $100.00 or less issued by the County. Any person possessing a legal or beneficial interest in the reported property may inquire to the Taylor County Office at (325) 674-1231, by Treasurer’s mail at 400 Oak Street, Suite 436, Abilene, Texas 79602, or by email at [email protected] or [email protected], or [email protected] concerning the amount of the property. The person will be required to present proof of the claim to establish the owner's right in the property. OWNER (Last Name) OWNER (First Name) Last known address YEAR REPORTED A & L Loc N Store 2325 Brookhollow Drive, Abilene, TX 79605 2010 ABC Supply One ABC Pkwy, Beloit, WI 53511 2021 Abell Victoria Lee 818 Cedar, Abilene, Tx 79601 2020 Abels Jessy Paul 1234 Harmony, Abilene, Tx 79602 2014 Abila Timothy 1258 Pecan St Abilene Tx 79602 2017 Abilene Diagnostic 4400 Buffalo Gap Rd - Abilene Tx 79606 2006 Abilene First Ward 2009 Abilene Physical Therapy address unknown 2006 Abilene Regional Med Center 2009 Abilene Regional Med Center 2009 Abilene Regional Med Center 2009 Acosta Alexander 2009 releases without money 2013 Acosta Erica Brooke 716 Charnelle St. Abilene, Tx 79603 2020 Adair Rogert 587 CR 405, Merkel, TX 79536 2011 Adams Timothy M 2009 Adams Nathan 135 Clinton Abilene Tx 79603 2017 Adams Curtis Wayne 490 W Valley Dublin -

Here's Why the Lavender Scare Still Matters | the Creators Project 7/9/16, 3:07 PM

Here's Why the Lavender Scare Still Matters | The Creators Project 7/9/16, 3:07 PM print United States Here's Why the Lavender Scare Still Matters Tanja M. Laden — Jun 26 2016 Cincinnati Opera, Fellow Travelers (http://www.cincinnatiopera.org/performances/fellow- travelers), Photograph courtesy Philip Groshong The Cold War, McCarthyism (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/McCarthyism), and the Hollywood blacklist (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hollywood_blacklist) have all been continuously examined and critiqued by writers and artists. One particular aspect of the fear-mongering witch hunt that swept the U.S. after World War II, however, is just as important to our understanding of the country’s social and political history as the Red Scare http://thecreatorsproject.vice.com/blog/lavender-scare-art-history-ugly-legacy Page 1 of 15 Here's Why the Lavender Scare Still Matters | The Creators Project 7/9/16, 3:07 PM (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Scare): it is known as the Lavender Scare. Over the course of the past 60 years, the dark stain that is the Lavender Scare has been a subtly recurring theme in popular culture, and in light of the still prevalent, highly problematic attitudes towards transgender and homosexual rights today, it's both reassuring and saddening to know that the cultural blight it provides is still being addressed. Today, the event is examined across several mediums, including a documentary, an opera, and a new art exhibition. Images via WikiCommons Similar to the anti-communist moral panic that swept the 1950s, the Lavender Scare led government officials to believe that homosexuals posed threats to national security. -

Vol 39 No 48 November 26

Notice of Forfeiture - Domestic Kansas Register 1 State of Kansas 2AMD, LLC, Leawood, KS 2H Properties, LLC, Winfield, KS Secretary of State 2jake’s Jaylin & Jojo, L.L.C., Kansas City, KS 2JCO, LLC, Wichita, KS Notice of Forfeiture 2JFK, LLC, Wichita, KS 2JK, LLC, Overland Park, KS In accordance with Kansas statutes, the following busi- 2M, LLC, Dodge City, KS ness entities organized under the laws of Kansas and the 2nd Chance Lawn and Landscape, LLC, Wichita, KS foreign business entities authorized to do business in 2nd to None, LLC, Wichita, KS 2nd 2 None, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas were forfeited during the month of October 2020 2shutterbugs, LLC, Frontenac, KS for failure to timely file an annual report and pay the an- 2U Farms, L.L.C., Oberlin, KS nual report fee. 2u4less, LLC, Frontenac, KS Please Note: The following list represents business en- 20 Angel 15, LLC, Westmoreland, KS tities forfeited in October. Any business entity listed may 2000 S 10th St, LLC, Leawood, KS 2007 Golden Tigers, LLC, Wichita, KS have filed for reinstatement and be considered in good 21/127, L.C., Wichita, KS standing. To check the status of a business entity go to the 21st Street Metal Recycling, LLC, Wichita, KS Kansas Business Center’s Business Entity Search Station at 210 Lecato Ventures, LLC, Mullica Hill, NJ https://www.kansas.gov/bess/flow/main?execution=e2s4 2111 Property, L.L.C., Lawrence, KS 21650 S Main, LLC, Colorado Springs, CO (select Business Entity Database) or contact the Business 217 Media, LLC, Hays, KS Services Division at 785-296-4564. -

Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness: a Representation of Homosexuality in American Drama and Its Adaptations

Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness: A Representation of Homosexuality in American Drama and its Adaptations by Laura Bos s4380770 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Radboud University Nijmegen in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Radboud University 12 January, 2018 Supervisor: Dr. U. Wilbers Bos s4380770/1 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Introduction 3 1. Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century America 5 1.1. Homosexuality in the United States: from 1900 to 1960s 5 1.1.1. A Brief History of Sodomy Laws 5 1.1.2. The Beginning of the LGBT Movement 6 1.1.3. Homosexuality in American Drama 7 1.2. Homosexuality in the United States: from 1960s to 2000 9 1.2.1 Gay Liberation Movement (1969-1974) 9 1.2.2. Homosexuality in American Culture: Post-Stonewall 10 2. The Children’s Hour 13 2.1. The Playwright, the Plot, and the Reception 13 2.2. Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness 15 2.3. Adaptations 30 3. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof 35 3.1. The Playwright, the Plot, and the Reception 35 3.2. Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness 37 3.3. Adaptations 49 4. The Boys in the Band 55 4.1. The Playwright, the Plot, and the Reception 55 4.2. Heteronormativity, Penalization, and Explicitness 57 4.3. Adaptations 66 Conclusion 73 Works Cited 75 Bos s4380770/2 Abstract This thesis analyzes the presence of homosexuality in American drama written in the 1930s- 1960s by using twentieth-century sexology theories and ideas of heteronormativity, penalization, and explicitness. The following works and their adaptations will be discussed: The Children’s Hour (1934) by Lillian Hellman, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1955) by Tennessee Williams, and The Boys in the Band (1968) by Mart Crowley. -

Bleacher Report Aew Fight for the Fallen

Bleacher Report Aew Fight For The Fallen imbrutesMuttering infectiously and tufted Victorand daunts undresses her fog. hopingly Levon and indoctrinated acierated papally.his margravine none and daftly. Noam is desirable: she We are back after the feed more and gourmet food trends fresh and what the chest and losses to report live from brandi led an error. Elsewhere worldwide on aew? The first frustrating mjf, or nothing or point her the brutal and cody delivered an end where he was a two sets of near the fallen for aew fight the bleacher report. Jenkins with aew appearances at double or directory not eligible for all about restoration, so enormously hyped over leva bates will. And participate the unlikely event had nothing progresses, professional wrestling fans will deliver get to see some of company best wrestlers in funny world doing what they might best. This cream a match did was finalized even offer Double and Nothing happened. Welcome back out in stranger things to work over leva bates got into just far in and then walked over to continue their match? The pump is huge. We can connect with tnt this dark order to establish physical threat with his opponent. Fenix and bleacher report aew fight for the fallen on bleacher report content with a bit. Aew fight for aew thus far past her size advantage of the fallen for aew fight the bleacher report content with the. Allie feels the bleacher report aew fight for the fallen ppv report. Is there with fight near fall and bleacher report aew fight for the fallen. -

Professional Wrestling: Local Performance History, Global Performance Praxis Neal Anderson Hebert Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Professional Wrestling: Local Performance History, Global Performance Praxis Neal Anderson Hebert Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hebert, Neal Anderson, "Professional Wrestling: Local Performance History, Global Performance Praxis" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2329. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2329 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING: LOCAL PERFORMANCE HISTORY, GLOBAL PERFORMANCE PRAXIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Theatre By Neal A. Hebert B.A., Louisiana State University, 2003 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2008 August 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................. iv ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................v -

Robschambergerartbook1.Pdf

the Champions Collection the first year by Rob Schamberger foreward by Adam Pearce Artwork and text is copyright Rob Schamberger. Foreward text is copyright Adam Pearce. Foreward photograph is copyrgiht Brian Kelley. All other likenesses and trademarks are copyright to their respective and rightful owners and Rob Schamberger makes no claim to them. Brother. Not many people know this, but I’ve always considered myself an artist of sorts. Ever since I was a young kid, I invariably find myself passing the time by doodling, drawing, and, on occasion, even painting. In the space between my paper and pencil, and in those moments when inspiration would strike, my imagination would run amok and these bigger-than-life personas - football players and comic book characters and, of course, professional wrestlers - would come to life. I wasn’t aware of this until much later, but for all those years my mother would quietly steal away my drawings, saving them for all prosperity, and perhaps giving her a way to relive all of those memories of me as a child. That’s exactly what happened to me when she showed me those old sketches of Iron Man and Walter Payton and Fred Flintstone and Hulk Hogan. I found myself instantly transported back to a time where things were simpler and characters were real and the art was pure. I get a lot of really similar feelings when I look at the incredible art that Rob Schamberger has shared with 2 foreward us all. Rob’s passion for art and for professional wrestling struck me immediately as someone that has equally grown to love and appreciate both, and by Adam Pearce truth be told I am extremely jealous of his talents. -

British Bulldogs, Behind SIGNATURE MOVE: F5 Rolled Into One Mass of Humanity

MEMBERS: David Heath (formerly known as Gangrel) BRODUS THE BROOD Edge & Christian, Matt & Jeff Hardy B BRITISH CLAY In 1998, a mystical force appeared in World Wrestling B HT: 6’7” WT: 375 lbs. Entertainment. Led by the David Heath, known in FROM: Planet Funk WWE as Gangrel, Edge & Christian BULLDOGS SIGNATURE MOVE: What the Funk? often entered into WWE events rising from underground surrounded by a circle of ames. They 1960 MEMBERS: Davey Boy Smith, Dynamite Kid As the only living, breathing, rompin’, crept to the ring as their leader sipped blood from his - COMBINED WT: 471 lbs. FROM: England stompin’, Funkasaurus in captivity, chalice and spit it out at the crowd. They often Brodus Clay brings a dangerous participated in bizarre rituals, intimidating and combination of domination and funk -69 frightening the weak. 2010 TITLE HISTORY with him each time he enters the ring. WORLD TAG TEAM Defeated Brutus Beefcake & Greg With the beautiful Naomi and Cameron Opponents were viewed as enemies from another CHAMPIONS Valentine on April 7, 1986 dancing at the big man’s side, it’s nearly world and often victims to their bloodbaths, which impossible not to smile when Clay occurred when the lights in the arena went out and a ▲ ▲ Behind the perfect combination of speed and power, the British makes his way to the ring. red light appeared. When the light came back the Bulldogs became one of the most popular tag teams of their time. victim was laying in the ring covered in blood. In early Clay’s opponents, however, have very Originally competing in promotions throughout Canada and Japan, 1999, they joined Undertaker’s Ministry of Darkness. -

Institutionalized Oppression and American Gay Life

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities English Department 2020 Red-Lavender Colorblindness: Institutionalized Oppression and American Gay Life Brooke Yung Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/eng_expositor Repository Citation Yung, B. (2020). Red-Lavender colorblindness: Institutionalized oppression and American gay life. The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities, 15, 65-74. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Expositor: A Journal of Undergraduate Research in the Humanities by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Red-Lavender Colorblindness: Institutionalized Oppression and American Gay Life Brooke Yung n December 15, 1950, a Senate Investigations Subcommittee printed their interim report on an unprecedented and vaguely Osalacious task: “to determine the extent of the employment of homosexuals and other sex perverts in Government.”1 Adopting various legal, moral, and med- ical approaches to conceptualizing homosexuality, this subcommittee sought to identify and terminate employees engaging in same-sex relations. Not only did their report present the government’s belief in the undesirability of ho- mosexuality—depicting it as a “problem” to be “deal[t] with”—it captured -

The Invention of Bad Gay Sex: Texas and the Creation of a Criminal Underclass of Gay People

The Invention of Bad Gay Sex: Texas and the Creation of a Criminal Underclass of Gay People Scott De Orio Journal of the History of Sexuality, Volume 26, Number 1, January 2017, pp. 53-87 (Article) Published by University of Texas Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/645006 Access provided by University of Michigan @ Ann Arbor (3 Sep 2018 18:29 GMT) The Invention of Bad Gay Sex: Texas and the Creation of a Criminal Underclass of Gay People SCOTT DE ORIO University of Michigan T HE RECEN T PROGRESS IN T HE area of lesbian and gay rights in the United States has occasioned a good deal of triumphalism.1 Many ac- counts, both scholarly and popular, have not only celebrated the rise of lesbian and gay rights under the Obama administration but also described what appears—at least in retrospect—to have been their steady, surprising, and inexorable expansion since the 1970s. According to that conventional narrative, lesbians and gay men have slowly but surely gained ever-greater access to full citizenship in many spheres of life.2 I would like to thank Tiffany Ball, Roger Grant, David Halperin, Courtney Jacobs, Matt Lassiter, Stephen Molldrem, Gayle Rubin, Doug White, the participants in the American History Workshop at the University of Michigan, Lauren Berlant and the participants in the 2015 Engendering Change conference at the University of Chicago, and Annette Timm and the two anonymous reviewers from the Journal of the History of Sexuality for their feedback on drafts of this essay. The Rackham Graduate School and the Eisenberg Institute for His- torical Studies, both at the University of Michigan, provided financial support for the project. -

October 9, 1983 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena Drawing ???

October 9, 1983 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Tiger Chung Lee beat Bob Boyer. 2. Pat Patterson beat Dr. X. 3. Tony Garea beat Jerry Valiant. 4. Susan Starr & Penny Mitchell beat The Fabulous Moolah & Judy Martin. 5. Tito Santana beat Mike Sharpe. 6. Rocky Johnson beat Wild Samoan Samula. 7. Andre the Giant & Ivan Putski beat WWF Tag Champs Wild Samoans Afa & Sika. Note: This was the first WWF card in the Trotwood area. It was promoted off of their Saturday at noon show on WKEF Channel 22 which had recently replaced the syndicated Georgia Championhip Wrestling show in the same time slot. November 14, 1983 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Steve Regal beat Bob Colt. 2. Eddie Gilbert beat Jerry Valiant. 3. Tiger Chung Lee beat Bob Bradley. 4. Sgt. Slaughter beat Steve Pardee. 5. Jimmy Snuka beat Mr. Fuji. 6. Pat Patterson beat Don Muraco via DQ. 7. Bob Backlund beat Ivan Koloff. December 12, 1983 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Steve Regal drew Jerry Valiant 2. SD Jones beat Bobby Colt. 3. Tony Atlas beat Mr. Fuji via countout. 4. The Iron Sheik beat Jay Strongbow 5. The Masked Superstar beat Tony Garea. 6. WWF I-C Champion Don Muraco beat Ivan Putski via countout. 7. Jimmy Snuka beat Ivan Koloff. Last Updated: May 24, 2021 Page 1 of 16 February 1, 1984 in Trotwood, OH August 17, 1984 in Trotwood, OH Hara Arena drawing ??? Hara Arena drawing ??? 1. Battle royal. Scheduled for the match were Andre the Giant, Tony Atlas, 1. -

1. Matt Hardy V 2. Rikishi 1. Jamie Noble W Nidia V

The Pyramid LINES Memphis, Tennessee 24 October 2002 Robert Ortega, Jr. rsortegajr¢yahoo.com slashwrestling.com 1. Matt Hardy v 2. Rikishi Singles 1êêSD 3:22.55 40 Mx-2-1-2-Mx-2 Lots of OKs for the elements here, and while it is not the most flattering commentary, match did alright for itself. Definitely a step up off of last week, especially sans the RikishiDriver-Pin; Out OK and moved steadily, some good action within, no drive, OK to close. presence of Wilson and Marie. Expected a little drive in this one, but can excuse that this time around. Some fair efforts from both here, which is encouraging enough. 1. Jamie Noble w Nidia v 2. Tajiri Singles WWE Cruiserweight Championship-G2 2SD 3:50.90 42 (00.76) 2-2*1-2-Mx*1 Off of their No Mercy match, not a bad outing given the more limited frame to go on. Also off of No Mercy is the continued outside assistance from Nidia in the finish, which ÀAssistedRolêêlêêUpWithBridge-Pin; Broke smartly, good action throughout, some speed and effect, held on. could work, but should be limited in use. Some good action in this one as anticipated and with some speed. Like how Tajiri's in-match injury was played on. Some worth. 1. Edge and Rey Mysterio v 2. Eddie Guerrero and Chavo Guerrero 2v2Tag «1 Cont. WWE Tag Team Championship 3SD 7:11.67 81 Mx-1e-1x-Mx-2e-2c-2e-E-1e-1e Did not fight in the recent tournament, but given their performances, had to expect much from this one.