The Venous System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Are Spider Veins of the Legs a Serious and a Dangerous Medical

1 Anti-aging Therapeutics Volume 9–2007 Prevention or Reversal of Deep Venous Insufficiency and Treatment: Why Are Spider Veins of the Legs a Serious and A Dangerous Medical Condition? Imtiaz Ahmad M.D., F.A.C.S a, b, Waheed Ahmad M.D., F.A.C.S c, d a Cardiothoracic and Vascular Associates (Comprehensive Vein Treatment Center), Hamilton, NJ, USA b Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, Hamilton, NJ, USA. c Comprehensive Vein Treatment Center of Kentuckiana, New Albany, IN 47150, USA. d Clinical professor of surgery, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA. ABSTRACT Spider veins (also known as spider hemangiomas) unlike varicose veins (dilated pre-existing veins) are acquired lesions caused by venous hypertension leading to proliferation of blood vessels in the skin and subcutaneous tissues due to the release of endothelial growth factors causing vascular neogenesis. More than 60% of the patients with spider veins of the legs have significant symptoms including pain, itching, burning, swelling, phlebitis, cellulites, bleeding, and ulceration. Untreated spider veins may lead to serious medical complications including superficial and deep venous thrombosis, aggravation of the already established venous insufficiency, hemorrhage, postphlebitic syndrome, chronic leg ulceration, and pulmonary embolism. Untreated spider vein clusters are also responsible for persistent low-grade inflammation; many recent peer- reviewed medical studies have shown a definite association of chronic inflammation with obesity, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer. Clusters of spider veins have one or more incompetent perforator veins connected to the deeper veins causing reflux overflow of blood that is responsible for their dilatation and eventual incompetence. -

Lower Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis

SECTION 5 Vascular System CHAPTER 34 Lower Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis Ariel L. Shiloh KEY POINTS • Providers can accurately detect lower extremity deep venous thrombosis with point-of- care ultrasound after limited training. • Compression ultrasound exams are as accurate as traditional duplex and triplex vascular ultrasound exams. • Compression ultrasound exam at only two sites, the common femoral vein and popliteal vein, permits rapid and accurate assessment of deep venous thrombosis. Background care providers can perform lower extremity compression ultrasonography exams rapidly Venous thromboembolic disease (VTE) is a and with high diagnostic accuracy to detect common cause of morbidity and mortality in DVT. 7–13 A meta-analysis of 16 studies showed hospitalized patients and is especially preva- that point-of-care ultrasound can accurately lent in critically ill patients.1–3 Approximately diagnose lower extremity DVTs with a pooled 70% to 90% of patients with an identified source sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 97%.14 of pulmonary embolism (PE) have a proxi- Traditional vascular studies, the duplex mal lower extremity deep venous thrombosis and triplex exams, use a combination of (DVT). Conversely, 40% to 50% of patients two-dimensional (2D) imaging with compres- with a proximal DVT have a concurrent pul- sion along with the use of color and/or spectral monary embolism at presentation, and simi- Doppler ultrasound. More recent studies have larly, in only 50% of patients presenting with a demonstrated that 2D compression ultrasound PE can a DVT be found.4–6 exams alone yield similar accuracy as tradi- Point-of-care ultrasound is readily available tional duplex or triplex vascular studies.9,11,15–17 as a diagnostic tool for VTE. -

Cardiovascular System 9

Chapter Cardiovascular System 9 Learning Outcomes On completion of this chapter, you will be able to: 1. State the description and primary functions of the organs/structures of the car- diovascular system. 2. Explain the circulation of blood through the chambers of the heart. 3. Identify and locate the commonly used sites for taking a pulse. 4. Explain blood pressure. 5. Recognize terminology included in the ICD-10-CM. 6. Analyze, build, spell, and pronounce medical words. 7. Comprehend the drugs highlighted in this chapter. 8. Describe diagnostic and laboratory tests related to the cardiovascular system. 9. Identify and define selected abbreviations. 10. Apply your acquired knowledge of medical terms by successfully completing the Practical Application exercise. 255 Anatomy and Physiology The cardiovascular (CV) system, also called the circulatory system, circulates blood to all parts of the body by the action of the heart. This process provides the body’s cells with oxygen and nutritive ele- ments and removes waste materials and carbon dioxide. The heart, a muscular pump, is the central organ of the system. It beats approximately 100,000 times each day, pumping roughly 8,000 liters of blood, enough to fill about 8,500 quart-sized milk cartons. Arteries, veins, and capillaries comprise the network of vessels that transport blood (fluid consisting of blood cells and plasma) throughout the body. Blood flows through the heart, to the lungs, back to the heart, and on to the various body parts. Table 9.1 provides an at-a-glance look at the cardiovascular system. Figure 9.1 shows a schematic overview of the cardiovascular system. -

Difference Between Vein and Venule Key Difference - Vein Vs Venule

Difference Between Vein and Venule www.differencebetween.com Key Difference - Vein vs Venule The veins are the blood vessels that carry blood towards the heart. It always has a low blood pressure. Except the pulmonary and the umbilical veins, all the remaining veins carry the deoxygenated blood. On the contrary, the arteries carry blood away from the heart. The veins have valves in them to prevent the black flow of blood and to maintain unidirectional blood flow. They are less muscular, larger and are located closer to the skin. Venules are very smaller veins. They are the ones that collect blood from the capillaries. The collected blood will be directed to the larger and medium veins where the blood is transported towards the heart again. Many venules unite to form larger veins. The key difference between Vein and Venule is, the vein is a larger blood vessel that carries blood towards the heart while, the venule is a smaller minute blood vessel that drains blood from capillaries to the veins. What is a Vein? The veins are larger blood vessels present in throughout the body. The main function of veins is to carry oxygen-poor blood back into the heart. Veins are classified into some categories such as, superficial veins, pulmonary veins, deep veins, perforator veins, communicating veins and systematic veins. The wall of the vein is thinner and less elastic than the wall of an artery. The walls of the veins consist three layers of tissues which are named as tunica externa, tunica media, and tunica intima. Veins also have larger and irregular lumen. -

Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD) Fact Sheet

FACT SHEET FOR PATIENTS AND FAMILIES Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD) What is peripheral vascular disease? Vascular disease is disease of the blood vessels (arteries and veins). Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) affects The heart receives blood, the areas that are “peripheral,” or outside your heart. sends it to The most common types of PVD are: the lungs to get oxygen, • Carotid artery disease affects the arteries and pumps that carry blood to your brain. It occurs when it back out. one or more arteries are narrowed or blocked by plaque, a fatty substance that builds up inside artery walls. Carotid artery disease can increase Veins carry Arteries carry your risk of stroke. It can also cause transient blood to your oxygen-rich [TRANZ-ee-ent] ischemic [iss-KEE-mik] attacks (TIAs). heart to pick blood from up oxygen. your heart TIAs are temporary changes in brain function to the rest of that are sometimes called “mini-strokes.” your body. • Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) often affects the arteries to your legs and feet. It is also caused by Healthy blood vessels provide oxygen plaque buildup, and can for every part of your body. cause pain that feels like a dull cramp or heavy tiredness in your hips or legs when • Venous insufficiency affects the veins, usually you exercise or climb stairs. in your legs or feet. Your veins have valves that This pain is sometimes Damaged Healthy keepvalve blood fromvalve flowing backward as it moves called claudication. If PAD toward your heart. If the valves stop working, blood worsens, it can cause cold Plaque can build backs up in your body, usually in your legs. -

Microlymphatic Surgery for the Treatment of Iatrogenic Lymphedema

Microlymphatic Surgery for the Treatment of Iatrogenic Lymphedema Corinne Becker, MDa, Julie V. Vasile, MDb,*, Joshua L. Levine, MDb, Bernardo N. Batista, MDa, Rebecca M. Studinger, MDb, Constance M. Chen, MDb, Marc Riquet, MDc KEYWORDS Lymphedema Treatment Autologous lymph node transplantation (ALNT) Microsurgical vascularized lymph node transfer Iatrogenic Secondary Brachial plexus neuropathy Infection KEY POINTS Autologous lymph node transplant or microsurgical vascularized lymph node transfer (ALNT) is a surgical treatment option for lymphedema, which brings vascularized, VEGF-C producing tissue into the previously operated field to promote lymphangiogenesis and bridge the distal obstructed lymphatic system with the proximal lymphatic system. Additionally, lymph nodes with important immunologic function are brought into the fibrotic and damaged tissue. ALNT can cure lymphedema, reduce the risk of infection and cellulitis, and improve brachial plexus neuropathies. ALNT can also be combined with breast reconstruction flaps to be an elegant treatment for a breast cancer patient. OVERVIEW: NATURE OF THE PROBLEM Clinically, patients develop firm subcutaneous tissue, progressing to overgrowth and fibrosis. Lymphedema is a result of disruption to the Lymphedema is a common chronic and progres- lymphatic transport system, leading to accumula- sive condition that can occur after cancer treat- tion of protein-rich lymph fluid in the interstitial ment. The reported incidence of lymphedema space. The accumulation of edematous fluid mani- varies because of varying methods of assess- fests as soft and pitting edema seen in early ment,1–3 the long follow-up required for diagnosing lymphedema. Progression to nonpitting and irre- lymphedema, and the lack of patient education versible enlargement of the extremity is thought regarding lymphedema.4 In one 20-year follow-up to be the result of 2 mechanisms: of patients with breast cancer treated with mastec- 1. -

Anatomy of the Large Blood Vessels-Veins

Anatomy of the large blood vessels-Veins Cardiovascular Block - Lecture 4 Color index: !"#$%&'(& !( "')*+, ,)-.*, $()/ Don’t forget to check the Editing File !( 0*"')*+, ,)-.*, $()/ 1$ ($&*, 23&%' -(0$%"'&-$(4 *3#)'('&-$( Objectives: ● Define veins, and understand the general principles of venous system. ● Describe the superior & inferior Vena Cava and their tributaries. ● List major veins and their tributaries in the body. ● Describe the Portal Vein. ● Describe the Portocaval Anastomosis Veins ◇ Veins are blood vessels that bring blood back to the heart. ◇ All veins carry deoxygenated blood. with the exception of the pulmonary veins(to the left atrium) and umbilical vein(umbilical vein during fetal development). Vein can be classified in two ways based on Location Circulation ◇ Superficial veins: close to the surface of the body ◇ Veins of the systemic circulation: NO corresponding arteries Superior and Inferior vena cava with their tributaries ◇ Deep veins: found deeper in the body ◇ Veins of the portal circulation: With corresponding arteries Portal vein Superior Vena Cava ◇Formed by the union of the right and left Brachiocephalic veins. ◇Brachiocephalic veins are formed by the union of internal jugular and subclavian veins. Drains venous blood from : ◇ Head & neck ◇ Thoracic wall ◇ Upper limbs It Passes downward and enter the right atrium. Receives azygos vein on its posterior aspect just before it enters the heart. Veins of Head & Neck Superficial veins Deep vein External jugular vein Anterior Jugular Vein Internal Jugular Vein Begins just behind the angle of mandible It begins in the upper part of the neck by - It descends in the neck along with the by union of posterior auricular vein the union of the submental veins. -

Incidence of Deep Venous Thrombosis and Stratification of Risk Groups in A

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Incidence of deep venous thrombosis and stratification of risk groups in a university hospital vascular surgery unit Incidência de trombose venosa profunda e estratificação dos grupos de risco em serviço de cirurgia vascular de hospital universitário 1 1 1 2 Alberto Okuhara *, Túlio Pinho Navarro , Ricardo Jayme Procópio , José Oyama Moura de Leite Abstract Background: There is a knowledge gap with relation to the true incidence of deep vein thrombosis among patients undergoing vascular surgery procedures in Brazil. This study is designed to support the implementation of a surveillance system to control the quality of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in our country. Investigations in specific institutions have determined the true incidence of deep vein thrombosis and identified risk groups, to enable measures to be taken to ensure adequate prophylaxis and treatment to prevent the condition. Objective: To study the incidence of deep venous thrombosis in patients admitted to hospital for non-venous vascular surgery procedures and stratify them into risk groups. Method: This was a cross-sectional observational study that evaluated 202 patients from a university hospital vascular surgery clinic between March 2011 and July 2012. The incidence of deep venous thrombosis was determined using vascular ultrasound examinations and the Caprini scale. Results: The mean incidence of deep venous thrombosis in vascular surgery patients was 8.5%. The frequency distribution of patients by venous thromboembolism risk groups was as follows: 8.4% were considered low risk, 17.3% moderate risk, 29.7% high risk and 44.6% were classified as very high risk. Conclusion: The incidence of deep venous thrombosis in vascular surgery patients was 8.5%, which is similar to figures reported in the international literature. -

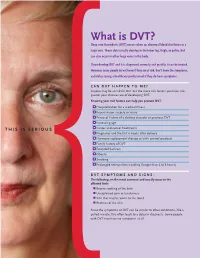

What Is Dvt? Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) Occurs When an Abnormal Blood Clot Forms in a Large Vein

What is DVt? Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurs when an abnormal blood clot forms in a large vein. These clots usually develop in the lower leg, thigh, or pelvis, but can also occur in other large veins in the body. If you develop DVT and it is diagnosed correctly and quickly, it can be treated. However, many people do not know if they are at risk, don’t know the symptoms, and delay seeing a healthcare professional if they do have symptoms. CAn DVt hAppen to me? Anyone may be at risk for DVT but the more risk factors you have, the greater your chances are of developing DVT. Knowing your risk factors can help you prevent DVt: n Hospitalization for a medical illness n Recent major surgery or injury n Personal history of a clotting disorder or previous DVT n Increasing age this is serious n Cancer and cancer treatments n Pregnancy and the first 6 weeks after delivery n Hormone replacement therapy or birth control products n Family history of DVT n Extended bed rest n Obesity n Smoking n Prolonged sitting when traveling (longer than 6 to 8 hours) DVt symptoms AnD signs: the following are the most common and usually occur in the affected limb: n Recent swelling of the limb n Unexplained pain or tenderness n Skin that may be warm to the touch n Redness of the skin Since the symptoms of DVT can be similar to other conditions, like a pulled muscle, this often leads to a delay in diagnosis. Some people with DVT may have no symptoms at all. -

Lower Limb Venous Drainage

Vascular Anatomy of Lower Limb Dr. Gitanjali Khorwal Arteries of Lower Limb Medial and Lateral malleolar arteries Lower Limb Venous Drainage Superficial veins : Great Saphenous Vein and Short Saphenous Vein Deep veins: Tibial, Peroneal, Popliteal, Femoral veins Perforators: Blood flow deep veins in the sole superficial veins in the dorsum But In leg and thigh from superficial to deep veins. Factors helping venous return • Negative intra-thoracic pressure. • Transmitted pulsations from adjacent arteries. • Valves maintain uni-directional flow. • Valves in perforating veins prevent reflux into low pressure superficial veins. • Calf Pump—Peripheral Heart. • Vis-a –tergo produced by contraction of heart. • Suction action of diaphragm during inspiration. Dorsal venous arch of Foot • It lies in the subcutaneous tissue over the heads of metatarsals with convexity directed distally. • It is formed by union of 4 dorsal metatarsal veins. Each dorsal metatarsal vein recieves blood in the clefts from • dorsal digital veins. • and proximal and distal perforating veins conveying blood from plantar surface of sole. Great saphenous Vein Begins from the medial side of dorsal venous arch. Supplemented by medial marginal vein Ascends 2.5 cm anterior to medial malleolus. Passes posterior to medial border of patella. Ascends along medial thigh. Penetrates deep fascia of femoral triangle: Pierces the Cribriform fascia. Saphenous opening. Drains into femoral vein. superficial epigastric v. superficial circumflex iliac v. superficial ext. pudendal v. posteromedial vein anterolateral vein GREAT SAPHENOUS VEIN anterior leg vein posterior arch vein dorsal venous arch medial marginal vein Thoraco-epigastric vein Deep external pudendal v. Tributaries of Great Saphenous vein Tributaries of Great Saphenous vein saphenous opening superficial epigastric superficial circumflex iliac superficial external pudendal posteromedial vein anterolateral vein adductor c. -

What You Need to Know About Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

What You Need to Know About Deep Vein Thrombosis What is a Deep Vein Thrombosis? A deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is a blood clot that forms in the veins in the body (usually in the leg or pelvis). What causes a Deep Vein Thrombosis? Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) sometimes occurs for no apparent reason. However, certain factors can increase the chance of developing a DVT: • Inactivity • Hospital stays and surgery • Damage to your blood vessel from an injury or trauma • Medical and genetic conditions • Pregnancy • Taking estrogen-based medicine such as hormonal birth control or hormone replacement therapy • Overweight or obese • Family history of DVT • Older age What are the symptoms of DVT? Only about half of the people who have a DVT have signs and symptoms. These signs and symptoms of a deep vein clot include: • Pain or tenderness, often starting in the calf. • Swelling, including the ankle & foot. • Warmth and redness of the area or a noticeable discoloration Vascular Surgery -1- How is a DVT diagnosed? Your doctor will ask you questions about your symptoms and if your symptoms suggest that a blood clot is likely, you could have one or all of the following tests: • Blood test for a D-dimer: this test measures the level of a compound released when blood clots are dissolving. A high level may mean you have Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT). • Imaging studies: o Ultrasound – This is the most common test for diagnosing deep vein blood clots. This test uses sound waves to create pictures of blood flowing through the arteries and veins in the affected leg. -

Comprehensive Review of the Superficial Veins of the Forearm from a Historical, Anatomical and Clinical Point of View

IJAE Vol. 124, n. 2: 142-152, 2019 ITALIAN JOURNAL OF ANATOMY AND EMBRYOLOGY Circulatory system Comprehensive review of the superficial veins of the forearm from a historical, anatomical and clinical point of view Lucas Alves Sarmento Pires1,2,*, Albino Fonseca Junior1,2, Jorge Henrique Martins Manaia1,2, Tulio Fabiano Oliveira Leite3, Marcio Antonio Babinski1,2, Carlos Alberto Araujo Chagas2 1 Medical Sciences Post Graduation Program, Fluminense Federal University, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2 Morphology Department, Fluminense Federal University, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 3 Interventional Radiology Unit, Radiology Institute, University of São Paulo Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil Abstract The superficial veins of the forearm are prone to possess different patterns of anastomosis. This is highly significant, as venipunctures in the upper limb are among the most performed procedures in the world and they often rely on the veins of the cubital fossa. In addition, the relationship of these veins to the cutaneous nerves are also prone to vary and are often uncer- tain. These veins are also manipulated in the creation of arteriovenous fistula for dialisis, which remains as the best choice of treatment for renal failure patients. Such fistulas are often per- formed on the wrist or the cubital fossa, with the cephalic vein or basilic vein. It is known that anatomical variations of the vessels and nerves on the cubital fossa may induce the profession- als to error, and one of the most common complications of venipuncture are accidental nerve puncture, which can lead to paresthesia and pain. We aim to perform a comprehensive review of the venous arrangements of the cubital fossa and their clinical aspects, as well as of veni- puncture from a historical perspective and of the complications of venipuncture and arterio- venous fistula from an anatomical point of view, with the purpose of compiling available data and help healthcare professionals to reduce puncture errors or arteriovenous fistula complica- tions and improve patient care.