The Closing of Civic Space in the Philippines Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toward an Enhanced Strategic Policy in the Philippines

Toward an Enhanced Strategic Policy in the Philippines EDITED BY ARIES A. ARUGAY HERMAN JOSEPH S. KRAFT PUBLISHED BY University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies Diliman, Quezon City First Printing, 2020 UP CIDS No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publishers. Recommended Entry: Towards an enhanced strategic policy in the Philippines / edited by Aries A. Arugay, Herman Joseph S. Kraft. -- Quezon City : University of the Philippines, Center for Integrative Studies,[2020],©2020. pages ; cm ISBN 978-971-742-141-4 1. Philippines -- Economic policy. 2. Philippines -- Foreign economic relations. 2. Philippines -- Foreign policy. 3. International economic relations. 4. National Security -- Philippines. I. Arugay, Aries A. II. Kraft, Herman Joseph S. II. Title. 338.9599 HF1599 P020200166 Editors: Aries A. Arugay and Herman Joseph S. Kraft Copy Editors: Alexander F. Villafania and Edelynne Mae R. Escartin Layout and Cover design: Ericson Caguete Printed in the Philippines UP CIDS has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of urls for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ______________________________________ i Foreword Stefan Jost ____________________________________________ iii Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem _____________________________v List of Abbreviations ___________________________________ ix About the Contributors ________________________________ xiii Introduction The Strategic Outlook of the Philippines: “Situation Normal, Still Muddling Through” Herman Joseph S. Kraft __________________________________1 Maritime Security The South China Sea and East China Sea Disputes: Juxtapositions and Implications for the Philippines Jaime B. -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

PW-0412-HOME-PRINTING.Pdf

Mga istorya mula Negros 3 Marcos sa Negros 9 Rebyu: Usapang Kanto 12 TOMO 17 ISYU 12 12 ABRIL 2019 Chico River Project: Pabor na pabor sa China Walang kaabog-abog na pinagkanulo ng rehimeng Duterte ang soberanya ng Pilipinas sa mga kontratang pautang ng China. Ang masahol dito, mga Pilipino ang magbabayad sa utang at sa pagkasira ng kalikasan. Sundan sa pahina 6-8 ART: MULA SA INFOGRAPHIC SERIES NG IBON FOUNDATION, “THE WORST THAT CAN HAPPEN WITH DUTERTE ADMINISTRATION’S LOANS FROM CHINA” PW 17-12.indd 1 4/8/2019 11:13:26 AM 2 PINOY WEEKLY | ABRIL 12, 2019 turing na bahagi ng laban kontra pasismo ang Halalan at pasismo Ihalalan. Hindi itinatago maging ng rehimeng Duterte ang pakay nito sa pagpapatakbo ng mga senador sa ilalim ng Hugpong ng Pagbabago: para makontrol ang Senado at mas mabilis at madulas na mailusot ang mga pakay ng rehimen. Kabilang na rito ang pagrepaso sa Saligang Batas at ang (pekeng) Pederalismo na inaasam-asam nito para lalong makopo ng dominanteng mga angkan at pangkat ang mga probinsiya. Marami na ang nagsasabi, pero kailangang banggitin pa rin: Mahalaga ang eleksiyon MELVIN POLLERO sa pagkasenador. Mahalaga ito sa laban para pigilan ang dominasyon o monopolyo batas na gusto nitong pati ang berdugong si Bato Sa loob ng burukrasya ng pangkatin ng rehimen sa maisabatas. Pero di pa nito dela Rosa at balimbing na si ng gobyerno, pinakilos ng kapangyarihan ng gobyerno. kopo ang Senado. Marami Francis Tolentino. rehimen ang militar at pulis Kasalukuyang nakalatag na itong tao, pero malakas Maraming dahilan para magpatawag ng mga na ang kontrol nito sa pa rin ang oposisyon (kahit para kuwestiyunin ang pagtitipon (mga seminar, burukrasya, sa pamamagitan hindi kasing-ingay o tapang sarbey na ito. -

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy Special Issue, December 2018, pp. 181-206 The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and ABS-CBN through the Prisms of Herman and Chomsky’s “Propaganda Model”: Duterte’s Tirade against the Media and vice versa Menelito P. Mansueto Colegio de San Juan de Letran [email protected] Jeresa May C. Ochave Ateneo de Davao University [email protected] Abstract This paper is an attempt to localize Herman and Chomsky’s analysis of the commercial media and use this concept to fit in the Philippine media climate. Through the propaganda model, they introduced the five interrelated media filters which made possible the “manufacture of consent.” By consent, Herman and Chomsky meant that the mass communication media can be a powerful tool to manufacture ideology and to influence a wider public to believe in a capitalistic propaganda. Thus, they call their theory the “propaganda model” referring to the capitalist media structure and its underlying political function. Herman and Chomsky’s analysis has been centered upon the US media, however, they also believed that the model is also true in other parts of the world as the media conglomeration is also found all around the globe. In the Philippines, media conglomeration is not an alien concept especially in the presence of a giant media outlet, such as, ABS-CBN. In this essay, the authors claim that the propaganda model is also observed even in the less obvious corporate media in the country, disguised as an independent media entity but like a chameleon, it © 2018 Menelito P. -

Appendix .Pdf

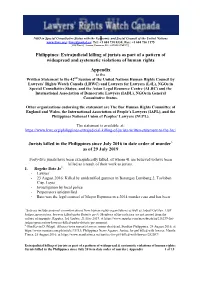

NGO in Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations www.lrwc.org; [email protected]; Tel: +1 604 738 0338; Fax: +1 604 736 1175 3220 West 13th Avenue, Vancouver, B.C. CANADA V6K 2V5 Philippines: Extrajudicial killing of jurists as part of a pattern of widespread and systematic violations of human rights Appendix to the Written Statement to the 42nd Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council by Lawyers’ Rights Watch Canada (LRWC) and Lawyers for Lawyers (L4L), NGOs in Special Consultative Status; and the Asian Legal Resource Centre (ALRC) and the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL), NGOs in General Consultative Status. Other organizations endorsing the statement are The Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales, the International Association of People’s Lawyers (IAPL), and the Philippines National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL). The statement is available at: https://www.lrwc.org/philippines-extrajudicial-killing-of-jurists-written-statement-to-the-hrc/ __________________________________________________________________________ Jurists killed in the Philippines since July 2016 in date order of murder1 as of 29 July 2019 Forty-five jurists have been extrajudicially killed, of whom 41 are believed to have been killed as a result of their work as jurists. 1. Rogelio Bato Jr2 - Lawyer - 23 August 2016: Killed by unidentified gunmen in Barangay Lumbang 2, Tacloban City, Leyte - Investigation by local police - Perpetrators unidentified - Bato was the legal counsel of Mayor Espinosa in a 2014 murder case and has been 1 Sources include personal communications from human rights organizations as well as Jodesz Gavilan. -

Philippine Studies Ateneo De Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines The Philippine Press System: 1811-1989 Doreen G. Fernandez Philippine Studies vol. 37, no. 3 (1989) 317–344 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Fri June 27 13:30:20 2008 Philippine Studies 37 (1989): 317-44 The Philippine Press System: 1811-1989 DOREEN G. FERNANDEZ The Philippine press system evolved through a history of Spanish colonization, revolution, American colonization, the Commonwealth, independence, postwar economy and politics, Martial Law and the Marcos dictatorship, and finally the Aquino government. Predictably, such a checkered history produced a system of tensions and dwel- opments that is not easy to define. An American scholar has said: When one speaks of the Philippine press, he speaks of an institution which began in the seventeenth century but really did not take root until the nineteenth century; which overthrew the shackles of three governments but became enslaved by its own members; which won a high degree of freedom of the press but for years neglected to accept the responsibilities inherent in such freedom. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

The Data Journalism Handbook

THE DATA JOURNALISM HANDBOOK Towards a Critical Data Practice Edited by Liliana Bounegru and Jonathan Gray 1 Bounegru & Gray (eds.) The Data Journalism Handbook “This is a stellar collection that spans applied and scholarly perspectives on practices of data journalism, rich with insights into the work of making data tell stories.” − Kate Crawford, New York University + Microsoft Research New York; author of Atlas of AI “Researchers sometimes suffer from what I call journalist-envy. Journalists, after all, write well, meet deadlines, and don’t take decades to complete their research. But the journalistic landscape has changed in ways that scholars should heed. A new, dynamic field—data journalism—is flourishing, one that makes the boundaries between our fields less rigid and more interesting. This exciting new volume interrogates this important shift, offering journalists and researchers alike an engaging, critical introduction to this field. Spanning the globe, with an impressive variety of data and purposes, the essays demonstrate the promise and limits of this form of journalism, one that yields new investigative strategies, one that warrants analysis. Perhaps new forms of collaboration will also emerge, and envy can give way to more creative relations.” − Wendy Espeland, Northwestern University; co-author of Engines of Anxiety: Academic Rankings, Reputation, and Accountability “It is now established that data is entangled with politics and embedded in history and society. This bountiful book highlights the crucial role of data journalists -

Padugo and Roar: Rebuffing and Side Tracking Performances in APEC Philippines 20151

International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 6, Issue 9, 2019, PP 1-11 ISSN 2394-6288 (Print) & ISSN 2394-6296 (Online) Padugo and Roar: Rebuffing and Side Tracking Performances in APEC Philippines 20151 Danilo Santos Cortez, Jr.* Assistant Professor, Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila, University of the City of Manila, General Luna St. corner Muralla St., Intramuros, Manila, and 1002 Metro Manila. Philippines. *Corresponding Author: Danilo Santos Cortez, Jr, Assistant Professor, Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila, University of the City of Manila, General Luna St. corner Muralla St., Intramuros, Manila, 1002 Metro Manila. Philippines. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper attempts to describe and analyze selected social performances during the Philippines’ hosting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) 2015 Summit in Manila, particularly the staging of “Padugo” (bloodletting) ritual by Lumads anti-APEC protesters and the deploying of Katy Perry’s “Roar” by the Civil Disturbance Management (CDM) Unit of the Philippine National Police (PNP). By applying social performance theory, I argued here that rebuffing and sidetracking performances of Padugo and Roar are ultimately socio-political acts, which are both always performative. These social performances represent competing versions of the social order, attempting to find resonance beyond the actual performances, as such could possibly influence public opinion and transform the socio-cultural, economic, and/or political status quo. Keywords: Social Performance, Performance Theory, Protest Ritual, Public Order Policing. INTRODUCTION ethnic dance of the Igorots rendered by the Ramon Obusan Folkloric Group, not even Ballet The Philippines became the world's biggest Manila's interpretation of 'Anting-Anting' or stage in the hosting of Asia-Pacific Economic amulet. -

Philippines: Reports of Corruption and Bribery

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 24 August 2006 PHL101564.E Philippines: Reports of corruption and bribery within the police force; government response; frequency of convictions of members of the police force accused of criminal activity (2004 - 2006) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa The Report on the Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer 2004 revealed that Filipinos considered the police to be the most corrupt institution or sector in their country (TI 9 Dec. 2004, 11). The following year, the police dropped to second place in the ranking of corrupt institutions as perceived by the public, behind political parties and the legislature, which tied for first place (ibid. 9 Dec. 2005, 18). Starting in 2000, surveys of efforts made by public and private agencies to combat corruption were conducted by the Quezon City- based non-profit social research organization, Social Weather Stations (SWS n.d.). The results indicated that the Philippine National Police (PNP) received a "bad" rating in 2005, a rating it retained in 2006 (Manila Standard 7 July 2006; The Manila Times 8 July 2006). Both Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and the chief director of the PNP, Edgar Aglipay, have acknowledged that corruption is a problem within the police force (Philippines 17 July 2003; INQ7 3 Jan. 2005; Manila Standard 11 Dec. 2004). In a 2003 statement, President Arroyo called police corruption a "serious problem" that was negatively affecting national security (Philippines 17 July 2003), while Aglipay remarked that "persistent allegations" of police corruption were contributing to a "crisis of confidence" within the force (INQ7 3 Jan. -

Radio Silence

From Radio Silence to …and back to normal? a Humanitarian Information Service from INTERNEWS in Guiuan, Eastern Samar Philippines FINAL REPORT Figure 1: Telecom mast in Guiuan, Eastern Samar, later to be used to put up Radyo Bakdaw’s antenna. 2 “The MIRA [Multi-Cluster Initial Rapid Assessment] findings indicate that communication with communities through radio is the best way to ensure communication with affected people at this stage of the emergency.”1 “People have little or no access to basic information through cell phones, internet and radio, TV or newspapers. Ensuring disaster survivors can communicate with each other and with aid agency responders is critical,” 2! “Information is like a light”3 “Thoughtful and cost-effective niche programmes led to disproportionately positive impacts (for example, Internews and MapAction)”4 1!Multi(Cluster!Initial!Rapid!Assessment!(MIRA)!(!Philippines!Typhoon!Haiyan,!November!2013! http://relieFweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/MIRA_Report_(_Philippines_Haiyan_FINAL.pdF!! 2!Under!Secretary!General!For!Humanitarian!AFFairs!&!Emergency!RelieF!Coordinator,!Valerie!Amos! Press!Remarks!on!the!Philippines,!22!November!2013! 3!interview!with!John!Ging!on!Radyo!Bakdaw,!Internews! http://www.internews.org/information(light! 4!Rapid!Review!oF!DFID’s!Humanitarian!Response!to!Typhoon!Haiyan!in!the!Philippines!–!Independent! Commission!For!Aid!Impact,!Report!32,!March!2014,!page!16.! http://icai.independent.gov.uk/reports/rapid(review(dfids(humanitarian(response(typhoon(haiyan( philippines/ 3 TABLE -

NSM Media Statistics Awards Criteria Month (NSM)

30th National 9th NSM Media Statistics Awards Criteria Month (NSM) Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority I. About the National Statistics Month Media Awards 1.1 National Statistics Month (N SM) Pursuant to Presidential Proclamation No. 647, “Declaring the Month of October of Every Year as the National Statistics Month”, the NSM is annually observed nationwide. The NSM aims to (a) promote, enhance, and instill awareness and appreciation of the importance and value of statistics to the different sectors of the society and (b) elicit the cooperation and support of the general public in upgrading the quality and standards of statistics in the country. Coinciding with the 14 th National Convention on Statistics, t his year’s 30 th NSM will carry the theme, “Data Innovation: Key to a Better Nation” which signifies the importance of innovation in the provision of quality statistics. Among the various activities of the month -long celebration is recognizing the contribution of media practitioners in the use and widening of public understanding of official statistics. 1.2 NSM Media Awards The NSM Media Awards aims to recognize the significant role and contributions of the media in promoting and popularizing official statistical information and in their advocacy in featuring data services from the Philippine Statistical System in television , print, and in online news service. Page 2 of 8 Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority II. Type of Awards Categories Type of Award Coverage 1. Individual Best Statistical Special feature or editorial type Reporting in Print of articles published in print Media media 2. Individual Best Statistical Special feature or editorial type Reporting in of articles published only in Online Media ¹ online media.