The Logos Foundation: the Rise and Fall of Christian Reconstructionism in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hansard 8 May 1990

Legislative Assembly 1101 8 May 1990 NOTE: There could be differences between this document and the official printed Hansard, Vol. 314 TUESDAY, 8 MAY 1990 Mr SPEAKER (Hon. J. Fouras, Ashgrove) read prayers and took the chair at 10 a.m. ASSENT TO BILLS Assent to the following Bills reported by Mr Speaker— Griffith University and Gold Coast College of Advanced Education Amalgamation Bill; Queensland University of Technology and Brisbane College of Advanced Education Amalgamation Bill; Police Service Administration Bill; Public Sector Management Commission Bill; Retail Shop Leases Act Amendment Bill; Legal Aid Act Amendment Bill. DISTINGUISHED VISITOR Hon. K. Coghill, MP (Victoria) Mr SPEAKER: I wish to extend a welcome to the Honourable Ken Coghill, MP, Speaker of the Legislative Assembly of Victoria, who is present in the Speaker's gallery today. Honourable members: Hear, hear! ELECTIONS TRIBUNAL Absence of Presiding Member Mr SPEAKER: I wish to inform the House that while the Honourable Mr Justice Derrington is absent from the Supreme Court of Queensland, the Honourable Mr Justice K. W. Ryan, CBE, will be the judge of the court who will preside at the sittings of the Elections Tribunal, petition No. 1 of 1990. This petition relates to the matter of the election of a member of the Legislative Assembly for the electoral district of Nicklin. PARLIAMENTARY REPORTING STAFF Death of Chief Reporter; Appointment of Acting Chief Reporter Mr SPEAKER: Honourable members, I regret to inform the House of the death on 22 April of Mr Peter Bradshaw Rohl, Chief Reporter, Parliamentary Reporting Staff. As a mark of respect, I ask all honourable members to stand for a period in silence. -

Warmsley Cornellgrad 0058F 1

ON THE DETECTION OF HATE SPEECH, HATE SPEAKERS AND POLARIZED GROUPS IN ONLINE SOCIAL MEDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Dana Warmsley December 2017 c 2017 Dana Warmsley ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ON THE DETECTION OF HATE SPEECH, HATE SPEAKERS AND POLARIZED GROUPS IN ONLINE SOCIAL MEDIA Dana Warmsley, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 The objective of this dissertation is to explore the use of machine learning algorithms in understanding and detecting hate speech, hate speakers and po- larized groups in online social media. Beginning with a unique typology for detecting abusive language, we outline the distinctions and similarities of dif- ferent abusive language subtasks (offensive language, hate speech, cyberbully- ing and trolling) and how we might benefit from the progress made in each area. Specifically, we suggest that each subtask can be categorized based on whether or not the abusive language being studied 1) is directed at a specific individ- ual, or targets a generalized “Other” and 2) the extent to which the language is explicit versus implicit. We then use knowledge gained from this typology to tackle the “problem of offensive language” in hate speech detection. A key challenge for automated hate speech detection on social media is the separation of hate speech from other instances of offensive language. We present a Logistic Regression classifier, trained on human annotated Twitter data, that makes use of a uniquely derived lexicon of hate terms along with features that have proven successful in the detection of offensive language, hate speech and cyberbully- ing. -

An Evaluation of Theonomic Neopostmillennialism Thomas D

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University Faculty Publications and Presentations School of Religion 1988 An Evaluation of Theonomic Neopostmillennialism Thomas D. Ice Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Ice, Thomas D., "An Evaluation of Theonomic Neopostmillennialism" (1988). Faculty Publications and Presentations. Paper 103. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/103 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Religion at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Evaluation of Theonomic Neopostmillennialism Thomas D. Ice Pastor Oak Hill Bible Church, Austin, Texas Today Christians are witnessing "the most rapid cultural re alignment in history."1 One Christian writer describes the last 25 years as "The Great Rebellion," which has resulted in a whole new culture replacing the more traditional Christian-influenced Ameri can culture.2 Is the light flickering and about to go out? Is this a part of the further development of the apostasy that many premillenni- alists say is taught in the Bible? Or is this "posf-Christian" culture3 one of the periodic visitations of a judgment/salvation4 which is furthering the coming of a posfmillennial kingdom? Leaders of the 1 Marilyn Ferguson, -

Psychological and Personality Profiles of Political Extremists

Psychological and Personality Profiles of Political Extremists Meysam Alizadeh1,2, Ingmar Weber3, Claudio Cioffi-Revilla2, Santo Fortunato1, Michael Macy4 1 Center for Complex Networks and Systems Research, School of Informatics and Computing, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA 2 Computational Social Science Program, Department of Computational and Data Sciences, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA 3 Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar 4 Social Dynamics Laboratory, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA Abstract Global recruitment into radical Islamic movements has spurred renewed interest in the appeal of political extremism. Is the appeal a rational response to material conditions or is it the expression of psychological and personality disorders associated with aggressive behavior, intolerance, conspiratorial imagination, and paranoia? Empirical answers using surveys have been limited by lack of access to extremist groups, while field studies have lacked psychological measures and failed to compare extremists with contrast groups. We revisit the debate over the appeal of extremism in the U.S. context by comparing publicly available Twitter messages written by over 355,000 political extremist followers with messages written by non-extremist U.S. users. Analysis of text-based psychological indicators supports the moral foundation theory which identifies emotion as a critical factor in determining political orientation of individuals. Extremist followers also differ from others in four of the Big -

The History of the Queensland Parliament, 1957–1989

14 . The demise of the Coalition and the Nationals governing alone, 1981–1983 In 1980, backroom plans had been already entertained for a stand-alone National Party government supplemented by a few Liberal ‘ministerialists’— opportunists who would cross over and side with whatever the next ministry turned out to be in order to remain part of the next government. Historically, ‘ministerialists’ were typically senior parliamentarians who, forgoing party loyalties, decided to collaborate as individuals in the formulation of a new government. After the 1980 election, however, any such musing was put on hold as the two conservative parties lapsed back into coalition. This time, the Nationals clearly imposed their dominance, taking the prime portfolios and consigning the ‘leftovers’ to the Liberals. Labor began to refer to the junior partners as ‘Dr Edwards and his shattered Liberal team’—the losers who were ‘now completely the captive of the National Party’ (QPD 1981:vol. 283, p. 7). Despite his vitriolic attacks against the Premier and the National-led government, Llew Edwards retained his position as Deputy Premier and Treasurer—positions he would keep until he was deposed by Terry White on the eve of the Coalition collapse in August 1983, although there was an unsuccessful attempt by dissident Liberals to remove Edwards in November 1981. When the Premier learned about the dissident Liberal plan to topple Edwards, with Angus Innes taking the lead, he declared Innes an ‘anti-coalitionist’ and someone with whom he would not work. Instead, Bjelke-Petersen began hatching plans to form a minority government with whomsoever among the Liberals who would give him support; and then to govern alone until mid-1982. -

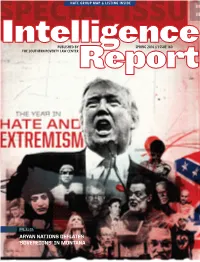

Aryan Nations Deflates

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men. -

People for the American Way Collection of Conservative Political Ephemera, 1980-2004

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb596nb6hz No online items Finding Aid to People for the American Way Collection of Conservative Political Ephemera, 1980-2004 Sarah Lopez The processing of this collection was made possible by the Center for the Comparative Study of Right-Wing Movements, Institute for the Study of Social Change, U.C. Berkeley, and by the generosity of the People for the American Way. The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. BANC MSS 2010/152 1 Finding Aid to People for the American Way Collection of Conservative Political Ephemera, 1980-2004 Collection number: BANC MSS 2010/152 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ The processing of this collection was made possible by the Center for the Comparative Study of Right-Wing Movements, Institute for the Study of Social Change, U.C. Berkeley, and by the generosity of the People for the American Way. Finding Aid Author(s): Sarah Lopez Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: People for the American Way collection of conservative political ephemera Date (inclusive): 1980-2004 Collection Number: BANC MSS 2010/152 Creator: People for the American Way Extent: 118 cartons; 1 box; 1 oversize box.circa 148 linear feet Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: This collection is comprised of ephemera assembled by the People For the American Way and pertaining to right-wing movements in the United States. -

Intellectually, Rushdoony Was Impressed by the Work of a Calvinist

BOOK REVIEWS Christian Reconstruction: Intellectually, Rushdoony was impressed by the R. J. Rushdoony and work of a Calvinist theorist, Cornelius Van Til, American Religious who argued for the significance of the intellectual Conservatism presuppositions from which people worked and of Michael Joseph McVicar the need for Christians to operate on the basis of University of North their own intellectual presuppositions, which in his Carolina Press, 2015 view were the only ones adequate for understanding $34.95, 326 pages the world. Rushdoony also came across, and was ISBN 9781469622743 sympathetic to, the free-market approach of Reviewed by Spiritual Mobilization. He developed his own Jeremy Shearmur political interpretation of Van Til, on the basis of which Christians should have nothing to do with f one considers libertarianism and classical the state—which, he thought, had usurped the liberalism in the mid-twentieth century, one sovereignty which belonged only to God. Instead, typically thinks of figures such as Mises, Hayek, they should build networks based on families and IAyn Rand, and Murray Rothbard. All of these played churches. In this context, Rushdoony was an important important roles. But if one pays attention only to and influential proponent of home schooling. them, one is liable to lose sight of an important point: Rushdoony was an omnivorous reader. He is best that religious ideas also played a significant role. understood as a fundamentalist Calvinist, who These ranged in their character from the differed radically in his view from the kind of Presbyterianism of J. Howard Pew and Jasper Crane ‘pre-millenial’ rapture theology to be found in (important as business people with strong intellectual the annotations in the Scofield Reference Bible and interests, and as financial supporters of classical as popularized in the best-selling Left Behind novels. -

Mcvicar CV (May 2020)

Michael J. McVicar 641 University Way Associate Professor Tallahassee, FL 32306-1520 Department of Religion 614-282-2229 Florida State University [email protected] PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION 2010 Ph.D., The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Major: Comparative Studies. Religious Studies. Supervisor: Hugh B. Urban. Dissertation: Reconstructing America: Religion, Conservatism, and the Political Theology of R. J. Rushdoony. (Doctoral dissertation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio). ProQuest Dissertations, 821470091. 2004 MA, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Major: Comparative Studies. Religion. Supervisor: Hugh B. Urban. Thesis: An experimental heuristic for exploring the relationship between the Church of God and the practice of serpent handling in Appalachia. Unpublished master’s thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. 2002 BA, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Major: History. Supervisor: Alan D. Beyerchen. Magna Cum Laude, with Distinction in Political Science and Honors in the Liberal Arts. 2001 BA, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio. Major: Political Science. Supervisor: John Champlin. Summa Cum Laude, with Distinction in Political Science and Honors in the Liberal Arts. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2019–present Associate Professor, Religion, Florida State University 2013–2019 Assistant Professor, Religion, Florida State University 2011–2013 Lecturer, Comparative Studies, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio 2010 Adjunct Professor, Religion, Ashland University, Ashland, Ohio 2003–2010 Graduate -

The History of the Queensland Parliament, 1957–1989

15 . The implosion of Joh Bjelke- Petersen, 1983–1987 The 1983 election ended the ‘constitutional crisis’ by providing the Nationals with exactly half the seats in the Parliament (41) and the opportunity to supplement their ministry with Liberal ministerialists who would agree to join the new government. The Premier had a number of options to secure his majority. Many of the surviving former Liberal ministers were not generally regarded as ‘anti-coalitionists’ in the previous government. The six potential ministerialists who might have been persuaded to change allegiances were: Norm Lee, Bill Lickiss, Brian Austin, Don Lane, Colin Miller and even Bill Knox. According to the Courier-Mail (15 July 1983), when two Coalition backbenchers, Bill Kaus and Bob Moore, had quit the Liberals and joined the Nationals in July, two Liberal ministers, Norm Lee and Bill Lickiss, already had indicated they would consider jumping ship. It was almost as if a race to defect was on. The two other Liberals to survive the 1983 poll, Terry White and Angus Innes, would not have been acceptable to the Premier and his senior ministers. In total, six of the eight Liberals had been ministers (although Miller had served for just 13 days after White was sacked and before the resignations of all the Liberals were accepted). Knox had been a minister since 1965 and Lee and Lickiss had been ministers since early 1975. They had some pedigree. Austin and Lane (and White) each had one parliamentary term as minister. Two Liberals, however, took the issue into their own hands. The day after the election, Austin and Lane had discussed the prospects of defecting and swapping parties, with Austin saying ‘I’m sick of this…I reckon we ought to give ’em the arse. -

Neo-Nazi Named Jeffrey Harbin Was End Birthright Citizenship

SPECIAL ISSUE IntelligencePUBLISHED BY SPRING 2011 | ISSUE 141 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTERReport THE YEAR IN HATE & EXTREMISM HATE GROUPS TOP 1000 Led by antigovernment ‘Patriot’ groups, the radical right expands dramatically for the second year in a row EDITORIAL The Arizonification of America BY MARK POTOK, EDITOR when even leading conser- As we explain in this issue, this dramatic growth of the rad- vatives worry out loud about the ical right for the second consecutive year is related to anger right-wing vitriol and demoniz- over the changing racial make-up of the country, the ailing ing propaganda so commonplace in economy and the spreading of demonizing propaganda and contemporary America, you’ve got other kinds of hate speech in the political mainstream. to be concerned about where our The white-hot political atmosphere is not limited to hard- country is headed. line nativist politicians, conspiracy-mongering cable news This January, former President hosts, or even openly radical hate groups. During the same George W. Bush, speaking in a month when most of these conservative commentaries were question-and-answer session written, the nation witnessed an extraordinary series of at Texas’ Southern Methodist events that highlighted the atmosphere of political extremism. University, warned that the nation seemed to be reliving its On Jan. 8, a Tucson man opened fire in a parking lot on worst anti-immigrant moments. “My point is, we’ve been U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, Democrat of Arizona, killing six through this kind of period of isolationism, protectionism, people, critically wounding the congresswoman and badly nativism” before, he said. -

The Public Eye, Winter 2005

TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL RESEARCH PublicEye ASSOCIATES WINTER 2005 • Volume XIX, No.3 The Rise of Dominionism Remaking America as a Christian Nation By Frederick Clarkson When Roy Moore, the Chief Justice of the Alabama State Supreme Court, installed a two-and-one-half-ton granite monument to the Ten Commandments in the Alabama state courthouse in Montgomery in June of 2001, he knew it was a deeply symbolic act. He was saying that God's laws are the foun- dation of the nation; and of all our laws. Or at least, they ought to be.1 The monument (wags call it “Roy’s rock”) was installed under cover of night – but Moore had a camera crew from Rev. D. James Kennedy’s Coral Ridge George Wallace Ministries on hand to record the historic event. Kennedy then sold videos of the installation and the Rightward Turn in Today’s Politics as a fundraiser for Moore’s legal defense. They knew he would need it. Alan Band/Keystone/Getty Images Alan Band/Keystone/Getty George Wallace, Governor of Alabama and presidential contender, in May 1972. he story of Roy’s rock epitomizes the Trise of what many are calling “domin- by Dan T. Carter ure would have upon poor, rural and ionism.” It is a story of how notions of “Bib- n the spring of 2005, Georgia’s Repub- minority voters. In the state of Georgia, for lical law” as an alternative to traditional, Ilican-controlled legislature passed a law example, there are over 159 counties but secular ideas of constitutional law are requiring all voters to appear at their proper only 56 DMV offices.