Englishness and Post-Imperial Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Prospectus

‘KNOWLEDGE IS THE MOST POWERFUL RESOURCE OF NATION BUILDING.’ A.P.J. ABDUL KALAM The University of Burdwan www.buruniv.ac.in Burdwan University: A Hub of Post Graduate Studies The University of Burdwan was established by the West Bengal act xxix of 1959 as a teaching and affiliating university on 15th June, 1960, with six postgraduate departments and thirty affiliated colleges. Now it has flourished into one of the premier institutions of higher education in India with thirty two postgraduate departments and 166 affiliated colleges in the district of Burdwan, Birbhum, Bankura and Hooghly. Administrative complex: located at Rajbati in the majestic Mahtab Manjil (the former palace of the maharaja of Burdwan) in Burdwan, the building boasts of a heritage status and is a tourist attraction. Academic complex: located at Golapbag (the garden of roses), about a mile away from Rajbati, is picturesque, sprawling and ideal for peaceful academic pursuits. CITY OFFICE CUM GUEST HOUSE: BLOCK EE-7/1, SECTOR-II, BIDHANAGAR (SALT LAKE) KOLKATA 700091 2 | Page Contents Course Guide Masters Programme M.Phil Programme Certificates and Diplomas Doctoral Programme Affiliated Colleges Offering PG Courses PG Funding and Fees Applying to Burdwan Accommodation Sport, Music and Student Societies Museums, Libraries and other Academic Student Welfare and Counseling Careers and Alumni Glimpse 3 | Page Burdwan University: A Hub of Post Graduate Studies The University has earned a great prestige in the academic fraternity in terms of providing excellent facilities covering libraries, laboratories, planetarium, and other infrastructure. The Departments in the university and colleges put topmost preference in admitting students of superb academic talent and acumen and their placement in lucrative jobs. -

(C) Crown Copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/23/83 Image

(c) crown copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/23/83 Image Reference:0029 (THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT). SECRET. COPY NO. CABINET 29 (36). Meeting of the Cabinet to be held in the Prime Minister's Room, House of Commons, on THURSDAY, 9th APRIL, 1936, at 12 Noon. AGENDUM. PROGRAMME OF NEW CONSTRUCTION FOR 1936. ' (Reference Cabinet 10 (56) (b) to (e)). Memorandum by the First Lord of the Admiralty CP. 105 (56) - circulated herewith. (Signed) M.P.A. HANKEY, Secretary to the Cabinet. 2, Whitehall Gardens, S.W.1. 8th April, 1956. '(THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT) SECRET. COPY NO. CABINET 29 (36). CONCLUSIONS of a Meeting of the Cahinet held in the prime Minister's room, House of Commons, on THURSDAY, 9th APRIL, 1936, at 12 noon. PRESENT: The Right Hon. Stanley Baldwin,- M.P. , Prime Minister. (in the Chair). The Right.. Hon. The Right Hon. J. Ramsay MacDonald, M. P. , Neville Chamberlain, M.P. , Lord president of the Council, Chancellor of the Exchequer. Tie Right Hon. The Right Hon. '. The Viscount Hailsham, Sir John Simon, G.C.S.I., Lord Chancellor. K.C.V.O., O.B.E., K.C., M.P., Secretary of State for Home Affairs. The Right Hon. The Right Hon. A. Duff Cooper, D.S.O., M.P., Malcolm MacDonald, M.P., Secretary of State for War, Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs. The Right Hen, The Most Hon. The Viscount Swinton, G.B.E., The Marquess of Zetland, M.C., Secretary of State for G.CS.I., G.CI.E. -

Mobilities in India

The Urban Book Series Editorial Board Margarita Angelidou, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece Fatemeh Farnaz Arefian, The Bartlett Development Planning Unit, UCL, Silk Cities, London, UK Michael Batty, Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, UCL, London, UK Simin Davoudi, Planning & Landscape Department GURU, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK Geoffrey DeVerteuil, School of Planning and Geography, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK Paul Jones, School of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia Andrew Kirby, New College, Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ, USA Karl Kropf, Department of Planning, Headington Campus, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK Karen Lucas, Institute for Transport Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK Marco Maretto, DICATeA, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Parma, Parma, Italy Ali Modarres, Tacoma Urban Studies, University of Washington Tacoma, Tacoma, WA, USA Fabian Neuhaus, Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada Steffen Nijhuis, Architecture and the Built Environment, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands Vitor Manuel Aráujo de Oliveira , Porto University, Porto, Portugal Christopher Silver, College of Design, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA Giuseppe Strappa, Facoltà di Architettura, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Roma, Italy Igor Vojnovic, Department of Geography, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA Jeremy W. R. Whitehand, Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK Claudia Yamu, Department of Spatial Planning and Environment, University of Groningen, Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands The Urban Book Series is a resource for urban studies and geography research worldwide. It provides a unique and innovative resource for the latest developments in the field, nurturing a comprehensive and encompassing publication venue for urban studies, urban geography, planning and regional development. -

London in the Sixties Free

FREE LONDON IN THE SIXTIES PDF Rainer Metzger | 368 pages | 06 Feb 2012 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500515631 | English | London, United Kingdom London s overview | Britannica We were a good two years into the s before we really began to feel that we had moved London in the Sixties from post-war austerity. By the end ofmost of us at last felt able to celebrate the prospects of more prosperous times ahead. Britain was in a post-war boom period and unemployment was very London in the Sixties. British goods and services were in great demand and we had a thriving manufacturing industry. The majority of ordinary working people had much more disposable income than their predecessors and were financially better off and more able to enjoy life. We were now living in peaceful times and although our country was saddled with wartime debt there was a greater sense of optimism and adventure, especially among the younger generation who were keen to embrace any new ideas that might help improve the mood of the country and even change the established British way of life. It started in Britain and changes happened very quickly. We were by now rapidly distancing ourselves from what we considered to be the dull and staid fifties culture. It was these earlys pop-groups that paved the way for an abundance of other British groups and solo artists to make their own breakthroughs in the music industry. It was not long before the fame of these and other London based fashion entrepreneurs spread around the world. England and more especially London quickly became a magnet for tourists from all over the globe. -

Great Expectations on Screen

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA Y TEORÍA DEL ARTE TESIS DOCTORAL GREAT EXPECTATIONS ON SCREEN A Critical Study of Film Adaptation Tesis presentada por Violeta Martínez-Alcañiz Licenciada en Periodismo y en Comunicación Audiovisual para la obtención del grado de Doctor Directoras de la Tesis Doctoral: Prof. Dra. Valeria Camporesi y Prof. Dra. Julia Salmerón Madrid, 2018 “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair” (Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities) “Now why should the cinema follow the forms of theater and painting rather than the methodology of language, which allows wholly new concepts of ideas to arise from the combination of two concrete denotations of two concrete objects?” (Sergei Eisenstein, “A dialectic approach to film form”) “An honest adaptation is a betrayal” (Carlo Rim) Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 13 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 15 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 21 Early expressions: between hostility and passion 22 Towards a theory on film adaptation 24 Story and discourse: semiotics and structuralism 25 New perspectives 30 CHAPTER 3. -

The Swinging Sixties

THE SWINGING SIXTIES The swinging sixties, the economical boom, A new way to make art, music and everything about the 60’s. “ SWINGING “ WHAT does “SWINGING“ mean? WHEN SOMETHING MOVES FORWARD AND BACKWARD, IT SWINGs. SWING STAnd FOR THE EASE OF DIFFUSION OF NEW INNOVATIVE TRENDS. WHAT WAS THE SWINGING 60’S? The swinging 60’s was a cultural revolution (or youth revolution) which started in UK and, then, it spread ALL IN the world. REVOLUTION So, This was a period of optimist, hedonism and a revolution in many fields: YOUTH MENTALITY; FASHION; MUSIC; ECONOMIC FIELD; ART; SOCIAL FIELDS. YOUTH REVOLUTION THE REVOLUTION STARTED FROM YOUNGER GENERATION: THEY BECAME MORE LIBERAL REBELLING AGAINST MANY SOCIAL VALUES; THEY DEMANDED SOCIAL/SEXUAL/RELIGIOUS FREEDOM; THEY LISTENED TO NEW MUSIC, WHICH TALKED ABOUT SOCIETY AND ITS PROBLEMS; THEY STARTED TO USE PSYCHEDELIC DRUGS; THEY PROTESTED AGAINST THE CONVENTIONS. FOCUS: THE HIPPIE GENERATION THE HIPPIE GENERATION (FLOWER CHILDREN) EMBRACED PHILOSOPHIES OF PEACE AND LOVE. THE LIVED IN COMMUNITY. THEY PROTESTED AGAINST THE STATUS QUO. THEY LIVING PROFESSING SEXUAL FREEDOM, DRUG USE, EQUALITY AND THE RESPECT FOR THE ENVIRONMENT. FASHION FREEDOM REVOLUTION STARTED FROM THE FASHION. SOME DESIGNERS INVENTED OR CHANGED THE WAY TO WEAR: MARY QUANT, FOR EXAMPLE, INVENTED THE MINISKIRT: A WAY TO EXPRESS FASHION FREEDOM; BARBARA HULANICKI: THE FOUNDER OF THE CLOTHES STORE biba, in london. NEW MUSIC IN THIS PERIOD THERE WAS AN EXPLOSION IN THE MARKET FOR MUSIC. NEW EMERGING BANDS BORN. SOME OF THESE WERE: THE BEATLES; ROLLING STONES; THE DOORS FOCUS: BOB DYLAN IN THIS PERIOD OF REVOLUTION MANY SINGERS WROTE SONG TO PROTEST. -

CCIM-11B.Pdf

Sl No REGISTRATION NOS. NAME FATHER / HUSBAND'S NAME & DATE 1 06726 Dr. Netai Chandra Sen Late Dharanindra Nath Sen Dated -06/01/1962 2 07544 Dr. Chitta Ranjan Roy Late Sahadeb Roy Dated - 01-06-1962 3 07549 Dr. Amarendra Nath Pal late Panchanan Pal Dated - 01-06-1962 4 07881 Dr. Suraksha Kohli Shri Krishan Gopal Kohli Dated - 30 /05/1962 5 08366 Satyanarayan Sharma Late Gajanand Sharma Dated - 06-09-1964 6 08448 Abdul Jabbar Mondal Late Md. Osman Goni Mondal Dated - 16-09-1964 7 08575 Dr. Sudhir Chandra Khila Late Bhuson Chandra Khila Dated - 30-11-1964 8 08577 Dr. Gopal Chandra Sen Gupta Late Probodh Chandra Sen Gupta Dated - 12-01-1965 9 08584 Dr. Subir Kishore Gupta Late Upendra Kishore Gupta Dated - 25-02-1965 10 08591 Dr. Hemanta Kumar Bera Late Suren Bera Dated - 12-03-1965 11 08768 Monoj Kumar Panda Late Harish Chandra Panda Dated - 10/08/1965 12 08775 Jiban Krishna Bora Late Sukhamoya Bora Dated - 18-08-1965 13 08910 Dr. Surendra Nath Sahoo Late Parameswer Sahoo Dated - 05-07-1966 14 08926 Dr. Pijush Kanti Ray Late Subal Chandra Ray Dated - 15-07-1966 15 09111 Dr. Pratip Kumar Debnath Late Kaviraj Labanya Gopal Dated - 27/12/1966 Debnath 16 09432 Nani Gopal Mazumder Late Ramnath Mazumder Dated - 29-09-1967 17 09612 Sreekanta Charan Bhunia Late Atul Chandra Bhunia Dated - 16/11/1967 18 09708 Monoranjan Chakraborty Late Satish Chakraborty Dated - 16-12-1967 19 09936 Dr. Tulsi Charan Sengupta Phani Bhusan Sengupta Dated - 23-12-1968 20 09960 Dr. -

The Consolidation of Youth Lifestyle in the 1960S: Swinging London Through the Drapers’ Record Magazine

Journalism and Mass Communication, April 2016, Vol. 6, No. 4, 221-225 doi: 10.17265/2160-6579/2016.04.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Consolidation of Youth Lifestyle in the 1960s: Swinging London Through The Drapers’ Record Magazine Maíra Zimmermann Armando Alvares Penteado Foundation (FAAP), São Paulo, Brazil This paper discusses how consumerism boosted youth lifestyle in the 1960s—mainly through modern magazines (particularly in Britain) and built a territorial symbolic identity through fashion. In the 1960s, the consolidation of youth culture becomes an international phenomenon. With the development of ready-to-wear, adolescents begin to be target as a consumer market. The music and fashion industries unite to create and advertise youth lifestyle. The fashion shifts from Paris to London. Magazine articles and publicity set the latest trends. The method applied is research in primary source—the British journal The Drapers’ Record—aiming to recognize fashion transformation and juvenilization in this period of time. The magazine shows ads and fashion editorials (mainly feminine), articles and news about fashion trend. There is also a brands guide for shoppers and retailers. The magazines used in the research are from 1964 to 1967, July and August issues, when the fall-winter trends are shown. From 1964 on, we notice the orientation towards a juvenile market and style, but these trends will only fully materialize through 1967. It leads to the conclusion that between 1965 and 1967 fashion juvenilization developed, reached its peak and global range. Keywords: youth culture, 1960s, trend, media Introduction: Consolidation of Youth Culture in the 1960s In the 1960s, the consolidation of youth culture becomes an international phenomenon. -

UGC 2018761 NOT WEBPAGE.Pdf

THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN Office of the Secretary, Council for the Under Graduate Studies in Arts, Science, Commerce etc. ADMISSION TO 2-YEAR B. ED. PROGRAMME in Self-financed B.Ed. Colleges only Session—2018-2020 INFORMATION SHEET [ Candidates are advised to follow the information given below ] [ Duration of Programme : 2 years l Medium of Instruction : Bengali or English ] 1. Submission of application form for admission to B.Ed. Programme will be made through on-line mode 2. For admission to B.Ed. Programme in Self-financed B.Ed. Colleges under B.U., submission of on-line application form is mandatory. 3. Mode of payment of application fees (Rs. 300/- + transaction charge) will be through Credit Card, Debit Card, Net Banking and Allahabad Bank e-challan. Allahabad Bank E-challan can be generated after submission of on-line form. Candidates are advised to take the print out of the e- challan on the basis of which payment can be made at any branch of Allahabad Bank. Last date of payment of application fee through e-challan is 23.07.2018. 4. On-line submiss ion of application form by a candidate does not automatically ensure his/her admission to the programme unless his/her original testimonials are found in order. Candidates, engaged in any other Course of Studies/Job/Full-time Research Work, shall not be allowed to pursue this course simultaneously. Fresh candidates must verify eligibility as in (6), age limit as in (8), availability of method subject(s) as in (11) be fo re on-line submission of the application form. -

1950S, 1960S and 1970S Word Search

1950s, 1960s and 1970s wordsearch B E A T L E S H E L E R O R V T E A P G G Y L O X S L A D E M I N I V L T U V C E R W S I D I L N O P Y G G I W T A S I B A L L R W R A T F A N C O R O N A T I O N M G B N A M W I N D A Q E S B T Y E E S L A C E A T W S P A C E R A C E M O B P A B N M A S W Q A N N A N P L A P E B O N E N N A M E A P L E A E S R G A R A T I O N I N G N L R A P P N O L U N A M E K I R T O P T R M A N S O M A N T E I V H Y B U N P L K I R E D D A S C H O P P E R B I K E O P E A G L E C O M I C Words to find: Beatles - An English rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. Comprising John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr, they are regarded as the most influential band of all time with well known hits, 'Hey Jude', 'I Want to Hold Your Hand' and 'Here comes the sun'. -

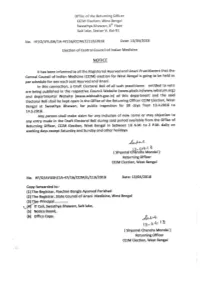

Centre for Distance and Online Education the University of Burdwan Golapbag, Burdwan, West Bengal

CENTRE FOR DISTANCE AND ONLINE EDUCATION THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN GOLAPBAG, BURDWAN, WEST BENGAL Advertisement No. CDOE/Sectt/Advt./5/2021-22/1, Dated: 10.7.2021 Applications are invited from Indian citizens for appointment of following teaching positions (unreserved) of Assistant Professor (Full time contractual), in The Centre for Distance and Online Education, The University of Burdwan with fixed pay @Rs.40, 000.00 per month. Sl. Name of the post Number of posts Subject/Discipline No. 1 Assistant Professor 02 Mathematics 2 Assistant Professor 02 Commerce 3 Assistant Professor 02 Computer Science 4 Assistant Professor 02 Bengali 5 Assistant Professor 02 English 6 Assistant Professor 02 Sanskrit 7 Assistant Professor 02 History 8 Assistant Professor 02 Political Science 9 Assistant Professor 02 Philosophy 10 Assistant Professor 02 Business Administration 11 Assistant Professor 02 Education Educational Qualifications:Applicants must have the minimum qualifications & experience as per relevant latest recruitment guidelines and latest Memorandum of the UGC/NCTE/AICTE/Department of Higher Education, Govt. of West Bengal, as applicable, for the appointment of Assistant Professor in the universities. Ph.D. degree in the respective subject is also essential. NCTE norms for B.Ed. will be followed for serial no. 11 only. Age limit: 50 Years. Fixed Pay: Rs.40, 000.00 (Rupees forty thousand only) per month. No other allowance is admissible. Nature of contract: Rues of The University of Burdwan will be applied in connection to the renewal of the contract. However, the authority reserves the right to terminate the contract by one-month notice, if services are found unsatisfactory. -

The Old War Office Building

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE The Old War Office Building A history The Old War Office Building …a building full of history Foreword by the Rt. Hon Geoff Hoon MP, Secretary of State for Defence The Old War Office Building has been a Whitehall landmark for nearly a century. No-one can fail to be impressed by its imposing Edwardian Baroque exterior and splendidly restored rooms and stairways. With the long-overdue modernisation of the MOD Main Building, Defence Ministers and other members of the Defence Council – the Department’s senior committee – have moved temporarily to the Old War Office. To mark the occasion I have asked for this short booklet, describing the history of the Old War Office Building, to be published. The booklet also includes a brief history of the site on which the building now stands, and of other historic MOD headquarters buildings in Central London. People know about the work that our Armed Forces do around the world as a force for good. Less well known is the work that we do to preserve our heritage and to look after the historic buildings that we occupy. I hope that this publication will help to raise awareness of that. The Old War Office Building has had a fascinating past, as you will see. People working within its walls played a key role in two World Wars and in the Cold War that followed. The building is full of history. Lawrence of Arabia once worked here. I am now occupying the office which Churchill, Lloyd-George and Profumo once had.