Use of Feces to Attract Insects by a Glittering-Bellied Emerald, Chlorostilbon Lucidus (Shaw, 1812) (Apodiformes: Trochilidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Basilinna Genus (Aves: Trochilidae): an Evaluation Based on Molecular Evidence and Implications for the Genus Hylocharis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 85: 797-807, 2014 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.35769 The Basilinna genus (Aves: Trochilidae): an evaluation based on molecular evidence and implications for the genus Hylocharis El género Basilinna (Aves: Trochilidae): una evaluación basada en evidencia molecular e implicaciones para el género Hylocharis Blanca Estela Hernández-Baños1 , Luz Estela Zamudio-Beltrán1, Luis Enrique Eguiarte-Fruns2, John Klicka3 and Jaime García-Moreno4 1Museo de Zoología, Departamento de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70- 399, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 2Departamento de Ecología Evolutiva, Instituto de Ecología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Apartado postal 70-275, 04510 México, D. F., Mexico. 3Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, University of Washington, Box 353010, Seattle, WA, USA. 4Amphibian Survival Alliance, PO Box 20164, 1000 HD Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [email protected] Abstract. Hummingbirds are one of the most diverse families of birds and the phylogenetic relationships within the group have recently begun to be studied with molecular data. Most of these studies have focused on the higher level classification within the family, and now it is necessary to study the relationships between and within genera using a similar approach. Here, we investigated the taxonomic status of the genus Hylocharis, a member of the Emeralds complex, whose relationships with other genera are unclear; we also investigated the existence of the Basilinna genus. We obtained sequences of mitochondrial (ND2: 537 bp) and nuclear genes (AK-5 intron: 535 bp, and c-mos: 572 bp) for 6 of the 8 currently recognized species and outgroups. -

Journal of Avian Biology JAV-00869 Wang, N

Journal of Avian Biology JAV-00869 Wang, N. and Kimball, R. T. 2016. Re-evaluating the distribution of cooperative breeding in birds: is it tightly linked with altriciality? – J. Avian Biol. doi: 10.1111/jav.00869 Supplementary material Appendix 1. Table A1. The characteristics of the 9993 species based on Jetz et al. (2012) Order Species Criteria1 Developmental K K+S K+S+I LB Mode ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter albogularis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter badius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter bicolor 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter brachyurus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter brevipes 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter butleri 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter castanilius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter chilensis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter chionogaster 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter cirrocephalus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter collaris 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter cooperii 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythrauchen 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythronemius 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter erythropus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter fasciatus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter francesiae 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gentilis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter griseiceps 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gularis 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter gundlachi 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter haplochrous 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter henicogrammus 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter henstii 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipiter imitator 0 0 0 0 1 ACCIPITRIFORMES -

NC2006 (Fauna) Doc. 4.1 (English Only/Únicamente En Inglés/Seulement En Anglais)

NC2006 (fauna) Doc. 4.1 (English only/Únicamente en inglés/Seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________ Nomenclature Committee Fauna Lima (Peru), 10 July 2006 Update on issues following CoP13 BIRD NOMENCLATURE 1. This document has been submitted by the zoologist of the Nomenclature Committee. 2. At the latest meeting of the Nomenclature Committee (fauna) in Geneva, on 23 May 2005, the zoologist of the Nomenclature Committee suggested to consider the Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World, edited by Dickinson1, as new standard reference for the bird nomenclature. She promised to provide a document for the next NC meeting in 2006 outlining the consequences of the adoption of this reference for the present nomenclature of CITES listed bird species. 3. The present document is based on an analysis carried out by Tim Inskipp (UNEP-WCMC), who compared the bird species so far accepted under CITES with the bird taxa in the The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World edited by Dickinson. 4. CITES Appendices currently include altogether 1,570 species or subspecies of birds. The adoption of the Howard and Moore Checklist edited by Dickinson would result in: – 141 one-to-one replacements (86 generic changes, 50 spelling changes, 5 name replacements) (see Annex 1); – 39 changes of species being reduced to subspecies level (see Annex 2); and – 45 split-listings where present subspecies are elevated to species level (see Annex 3). 5. One-to-one replacements will create no implementation problem as in the case of re-exports old documents the old scientific names can be easily be related to the new valid names. -

Proposals 2020-D

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2020-D 30 March 2020 No. Page Title 01 02 Revise the linear sequence of the Trochilini 02 07 Add Graylag Goose Anser anser to the US list 03 09 Add Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus to the US list 04 10 Add European Golden-Plover Pluvialis apricaria to the US list 05 12 Add Tahiti Petrel Pseudobulweria rostrata to the US list 06 13 Add Dark-billed Cuckoo Coccyzus melacoryphus to the US list 07 15 Add Red-backed Shrike Lanius collurio to (a) the Main List or (b) the Appendix 08 21 Add Long-legged Buzzard Buteo rufinus to the Main List 09 22 Retain the English name Comb Duck for Sarkidiornis sylvicola 10 26 Add Amazilia Hummingbird Amazilis amazilia to the Main List 1 2020-D-1 N&MA Classification Committee pp. 289-303 Revise the linear sequence of the Trochilini We recently passed two proposals (2020-A-2, 2020-A-3) that markedly changed the generic classification of the hummingbird tribe Trochilini, based on the phylogeny of McGuire et al. (2014) and the new classification of Stiles et al. (2017). Here we propose a new linear sequence using the revised names, based on these sources and an additional recent paper (Hernández- Baños et al. 2020). Stiles et al. (2017) split the tree from McGuire et al. (2014) into four parts for convenience; these trees were used in Proposal 2020-A-2 and are reproduced below. In the original phylogeny in McGuire et al. (2014), these trees are connected as follows: A and B are sister groups (although with little support), C and D are sister groups, and A+B and C+D are sister groups. -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Avian Influenza Infections in Nonmigrant Land Birds in Andean Peru

DOI: 10.7589/2011-02-052 Journal of Wildlife Diseases, 48(4), 2012, pp. 910–917 # Wildlife Disease Association 2012 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UDORA - University of Derby Online Research Archive AVIAN INFLUENZA INFECTIONS IN NONMIGRANT LAND BIRDS IN ANDEAN PERU Richard A. J. Williams,1,2,6 Karen Segovia-Hinostroza,3 Bruno M. Ghersi,3,4 Victor Gonzaga,4 A. Townsend Peterson,1 and Joel M. Montgomery4,5 1 Biodiversity Institute, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA 2 Departamento de Zoologı´a y Antropologı´aFı´sica, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, C/Jose´ Antonio Novais, 2 Ciudad Universitaria, 28040 Madrid, Spain 3 Facultad de Mecicina Veterinaria de Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Av. Circunvalacio´n Cdra. 28 San Borja, Lima, Peru 4 United States Naval Medical Research Center Detachment, Unit 6, Av. Venezuela Cdra. 36, Callao 2, Lima, Peru 5 Current address: International Emerging Infections Program, GDDER-KenyaCDC-KenyaMbagathi Rd, Off Mbagathi Way, PO Box 606, Village Market 00621, Nairobi, Kenya 6 Corresponding author (email: [email protected]) ABSTRACT: As part of ongoing surveillance for avian influenza viruses (AIV) in Peruvian birds, in June 2008, we sampled 600 land birds of 177 species, using real-time reverse-transcription PCR. We addressed the assumption that AIV prevalence is low or nil among land birds, a hypothesis that was not supported by the results—rather, we found AIV infections at relatively high prevalences in birds of the orders Apodiformes (hummingbirds) and Passeriformes (songbirds). -

Chlorostilbon Sp. an Unexpected Species in the Chota Valley

UNIVERSIDAD DE INVESTIGACIÓN DE TECNOLOGÍA EXPERIMENTAL YACHAY Escuela de Ciencias Biológicas e Ingeniería TÍTULO: Phylogeography of hummingbird by means of DNA analysis and taxonomic classification: Chlorostilbon sp. an unexpected species in the Chota valley Trabajo de integración curricular presentado como requisito para la obtención del título de Bióloga Autora: Quinga Nasimba Mayra Vanessa Tutor: Dr. Tellkamp Tietz Markus Patricio Urcuquí, Abril 2021 Urcuquí, 24 de junio de 2021 SECRETARÍA GENERAL (Vicerrectorado Académico/Cancillería) ESCUELA DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS E INGENIERÍA CARRERA DE BIOLOGÍA ACTA DE DEFENSA No. UITEY-BIO-2021-00014-AD A los 24 días del mes de junio de 2021, a las 10:30 horas, de manera virtual mediante videoconferencia, y ante el Tribunal Calificador, integrado por los docentes: Presidente Tribunal de Defensa Dr. SANTIAGO VISPO, NELSON FRANCISCO , Ph.D. Miembro No Tutor Dr. ALVAREZ BOTAS, FRANCISCO JAVIER , Ph.D. Tutor Dr. TELLKAMP TIETZ, MARKUS PATRICIO , Ph.D. El(la) señor(ita) estudiante QUINGA NASIMBA, MAYRA VANESSA, con cédula de identidad No. 1725200198, de la ESCUELA DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS E INGENIERÍA, de la Carrera de BIOLOGÍA, aprobada por el Consejo de Educación Superior (CES), mediante Resolución RPC-SO-37-No.438-2014, realiza a través de videoconferencia, la sustentación de su trabajo de titulación denominado: Phylogeography of hummingbird by means of DNA analysis and taxonomic classification: Chlorostilbon sp. an unexpected species in the Chota valley, previa a la obtención del título de BIÓLOGO/A. El citado trabajo de titulación, fue debidamente aprobado por el(los) docente(s): Tutor Dr. TELLKAMP TIETZ, MARKUS PATRICIO , Ph.D. Y recibió las observaciones de los otros miembros del Tribunal Calificador, las mismas que han sido incorporadas por el(la) estudiante. -

Breeds on Islands and Along Coasts of the Chukchi and Bering

FAMILY PTEROCLIDIDAE 217 Notes.--Also known as Common Puffin and, in Old World literature, as the Puffin. Fra- tercula arctica and F. corniculata constitutea superspecies(Mayr and Short 1970). Fratercula corniculata (Naumann). Horned Puffin. Mormon corniculata Naumann, 1821, Isis von Oken, col. 782. (Kamchatka.) Habitat.--Mostly pelagic;nests on rocky islandsin cliff crevicesand amongboulders, rarely in groundburrows. Distribution.--Breedson islandsand alongcoasts of the Chukchiand Bering seasfrom the DiomedeIslands and Cape Lisburnesouth to the AleutianIslands, and alongthe Pacific coast of western North America from the Alaska Peninsula and south-coastal Alaska south to British Columbia (QueenCharlotte Islands, and probablyelsewhere along the coast);and in Asia from northeasternSiberia (Kolyuchin Bay) southto the CommanderIslands, Kam- chatka,Sakhalin, and the northernKuril Islands.Nonbreeding birds occurin late springand summer south along the Pacific coast of North America to southernCalifornia, and north in Siberia to Wrangel and Herald islands. Winters from the Bering Sea and Aleutians south, at least casually,to the northwestern Hawaiian Islands (from Kure east to Laysan), and off North America (rarely) to southern California;and in Asia from northeasternSiberia southto Japan. Accidentalin Mackenzie (Basil Bay); a sight report for Baja California. Notes.--See comments under F. arctica. Fratercula cirrhata (Pallas). Tufted Puffin. Alca cirrhata Pallas, 1769, Spic. Zool. 1(5): 7, pl. i; pl. v, figs. 1-3. (in Mari inter Kamtschatcamet -

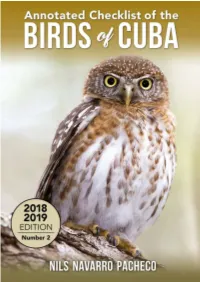

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba No. 2, 2018

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 2 2018-2019 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Cuban Pygmy Owl (Glaucidium siju), Peralta, Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2017 Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2018 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2018 ISBN: 9781790608690 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. He is a freelance author and an internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as curator of the herpetological collection of the Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he described several new species of lizards and frogs for Cuba. Nils has been travelling throughout the Caribbean Islands and Central America working on different projects related to the conservation of biodiversity, with a particular focus on amphibians and birds. He is the author of the book Endemic Birds of Cuba, A Comprehensive Field Guide, which, enriched by his own illustrations, creates a personalized field guide structure that is both practical and useful, with icons as substitutes for texts. -

Chlorostilbon Notatus (Blue-Chinned Sapphire)

UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology Chlorostilbon notatus (Blue-chinned Sapphire) Family: Trochilidae (Hummingbirds) Order: Trochilformes (Hummingbirds) Class: Aves (Birds) Fig. 1. Blue-chinned sapphire, Chlorostilbon notatus. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue-chinned_sapphire, downloaded 17 February 2017] TRAITS. The blue-chinned sapphire Chlorostilbon notatus, formerly known as Chlorestes notata, is a hummingbird with a short and fairly straight beak, with a black upper and reddish lower bill (Fig. 1). Length of males is 8-9.7cm, females 7-8cm, weight roughly 3-4.5g (Handbook of the Birds of the World, 2017). The male has predominantly green feathers, much darker on top, with white thighs, a metallic blue tail, and blue upper throat/chin. The female has green patched white underparts (Planet of birds, 2011). DISTRIBUTION. Widespread over South America ranging from Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, Grenada, French Guiana, Suriname, Guyana, Brazil, Trinidad (Fig. 2). There have been occasional records of this species in Tobago (IUCN, 2017). UWI The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago Ecology HABITAT AND ACTIVITY. Found in habitats ranging from savannas, plantations, open woodlands, fields, town gardens, forests. It can also be found in cultivated areas with large trees and is diurnal in activity. The species is characterized as 'quite common' in some parts of its range (Stotz et al., 1996), and is considered as Least Concern by the IUCN (2017). FOOD AND FEEDING. C. notatus feeds on nectar from a range of brightly coloured, scented, tubular-shaped small flowers of trees, shrubs, herbs and epiphytes (Fig. -

THE HYBRID ORIGIN of a VENEZUELAN Trochllid, AMAZILIA DISTANS WETMORE & PHELPS 1956

SHORTCOMMUNICATIONS ORNITOWGIA NEOTROPICAL 8: 107-112, 199; @ The Neotropical Ornithological Society Taxonomy THE HYBRID ORIGIN OF A VENEZUELAN TROCHlLID, AMAZILIA DISTANS WETMORE & PHELPS 1956 André-A. Weller & Karl-L. Schuchmann Alexander Koenig Zoological Research Institute and Zoological Museum, Oept. of Ornithology, Working Group: Biology and Phylogeny of Tropical Birds, Adenauerallee 160, 0-53113 Bonn, Germany. words: Amazilia distans, Amazilia fimbriata, Hylocharis cyanus, hybridization, Táchira, Venezuela. INTRODUCTION Institution (USNM) bird collection (Colección Amazilia di5tan5 was described as an endemic Ornitológica Phelps [COP # 60790], Caracas, from SW Táchira, Venezuela (Wetmore & Phelps presently on loan to USNM, as USNM # 1956), and it occupies an isolated position among 461965; cf. Deignan 1961) was examined and the 97 Venezuelan hummingbird species. The compared directly with skins of other taxa reasons for this are that the taxon was discovered (Amazilia, other genera). Data from Amazilia relatively recently and that only one skin specimens in other museums were also included specimen exists. Although the validity of this in the comparisons (see "Acknowledgments"). species has not been questioned by later authors Measurements, rounded to the nearest 0.1 mm (Mayr 1971, Meyer de Schauensee & Phelps (Fig. 2), were made using a digital caliper. Plum- 1978, Sibley & Monroe 1990 among others), and age colors were determined by visual inspection although subsequent, unconfirmed observations under natural light. Because of the presence of of A. di5tan5 have been made, almost nothing is iridescence, morphological evaluation of typical known of its biological or ecological character- hummingbird colors depends to some extent on istics (reviewed in Collar et al. 1992). As a result the subjective judgement of the taxonomist (see of its apparent extreme rarity and its relatively also Howell 1993); vernacular names were ac- threatened habitat, which can be described as cordingly used here to describe colors. -

Check-List of Birds of the World

i MMMMMmtnim iininii i ninimii iiii iii — mm m m WPwniwmHWWWWB"HHIIim i m i limn iJ PLEASE DO NOT REMOVE FROM ROOM 503 11 ,- BIRD DEPT. MUS. COMP. ZOOLl ! CHECK-LIST OF BIRDS OF THE WORLD VOLUME V LONDON : HUMPHREY MILPORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS CHECK-LIST OF BIRDS OF THE WORLD VOLUME V BY JAMES LEE PETERS CURATOR OF BIRDS, MUSEUM OF COMPARATIVE ZOOLOGY AT HARVARD COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE Original printing by HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS IN 1945 Reprinted by MUSEUM OF COMPARATIVE ZOOLOGY AT HARVARD COLLEGE IN 1955 COPTRIGHT, 1945 BT THE PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD COLLEGE REPRINTED BY PHOTO-LITHOGRAPHY SPAULDING-MOSS COMPANY BOSTON INTRODUCTION No innovations have been adopted in this volume; the gen- eral scope, as outlined in the introduction to the first volume, with minor changes explained in the introductions to subse- quent volumes, still stands. A little more than half of the present volume is taken by the hummingbirds. The arrangement of this family is essentially that adopted by Eugene Simon in his Histoire Naturelle des Trochilidae (Paris, 1921), but I have not been able to follow all of his generic refinements or some of his interpretations of the Rules of Zoological Nomenclature. Nevertheless, Simon's arrangement is probably the best to date for a family that defies any attempt at a logical linear classification. Generic differentiation has been much over- done in the Trochilidae; too much emphasis has been laid on secondary sexual characters of the males; a better system could probably be evolved from a classification based on the females, but the time element prevented my undertaking it.