Gowanus Pathways. a Framework to Support Community Resilience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Explore Gowanus

park helps to capture and and capture to helps park sponge and Gowanus Canal Conservancy. Conservancy. Canal Gowanus and banks of the Gowanus Canal. The The Canal. Gowanus the of banks Department of Sanitation of New York York New of Sanitation of Department the street end rain gardens along the the along gardens rain end street the with a collaborative effort between the the between effort collaborative a with is about 1,800 square feet surrounding surrounding feet square 1,800 about is green space. This green space began began space green This space. green open to the public called sponge park. It It park. sponge called public the to open flow tanks. The Salt Lot also provides provides also Lot Salt The tanks. flow Self-Guided Tour Self-Guided commercial building esplanade that is is that esplanade building commercial - over sewage combined two the for site This site of new luxury residential and and residential luxury new of site This final stop. This is the second proposed proposed second the is This stop. final ou have now reached your fifth stop. stop. fifth your reached now have ou Y t the dead end you have reached the the reached have you end dead the t A 7 THE SALT LOT SALT THE 5 ESPLANADE 365 BOND ST BOND 365 ESPLANADE hood starts to change here. change to starts hood park along the edge. the along park - neighbor the as note Take past. the water. Here you can see the sponge sponge the see can you Here water. GOWANUS point source of pollution in the canal in in canal the in pollution of source point ing lot and towards the edge of the the of edge the towards and lot ing like much now but this was a major major a was this but now much like - park Foods Whole the through Walk gas processing plants. -

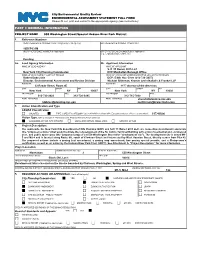

550 Washington Street/Special Hudson River Park District 1

City Environmental Quality Review ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT FULL FORM Please fill out, print and submit to the appropriate agency (see instructions) PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION PROJECT NAME 550 Washington Street/Special Hudson River Park District 1. Reference Numbers CEQR REFERENCE NUMBER (To Be Assigned by Lead Agency) BSA REFERENCE NUMBER (If Applicable) 16DCP031M ULURP REFERENCE NUMBER (If Applicable) OTHER REFERENCE NUMBER(S) (If Applicable) (e.g., Legislative Intro, CAPA, etc.) Pending 2a. Lead Agency Information 2b. Applicant Information NAME OF LEAD AGENCY NAME OF APPLICANT SJC 33 Owner 2015 LLC New York City Planning Commission DCP Manhattan Borough Office NAME OF LEAD AGENCY CONTACT PERSON NAME OF APPLICANT’S REPRESENTATIVE OR CONTACT PERSON Robert Dobruskin DCP: Edith Hsu-Chen (212-720-3437) Director, Environmental Assessment and Review Division Michael Sillerman, Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP ADDRESS ADDRESS 22 Reade Street, Room 4E 1177 Avenue of the Americas CITY STATE ZIP CITY STATE ZIP New York NY 10007 New York NY 10036 TELEPHONE FAX TELEPHONE FAX 212-720-3423 212-720-3495 212-715-7838 EMAIL ADDRESS EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 3. Action Classification and Type SEQRA Classification UNLISTED TYPE I; SPECIFY CATEGORY (see 6 NYCRR 617.4 and NYC Executive Order 91 of 1977, as amended): 617.4(6)(v) Action Type (refer to Chapter 2, “Establishing the Analysis Framework” for guidance) LOCALIZED ACTION, SITE SPECIFIC LOCALIZED ACTION, SMALL AREA GENERIC ACTION 4. Project Description: The applicants, the New York City Department of City Planning (DCP) and SJC 33 Owner 2015 LLC, are requesting discretionary approvals (the “proposed actions”) that would facilitate the redevelopment of the St. -

July 8 Grants Press Release

CITY PARKS FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES 109 GRANTS THROUGH NYC GREEN RELIEF & RECOVERY FUND AND GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC GRANT APPLICATION NOW OPEN FOR PARK VOLUNTEER GROUPS Funding Awarded For Maintenance and Stewardship of Parks by Nonprofit Organizations and For Free Live Performances in Parks, Plazas, and Gardens Across NYC July 8, 2021 - NEW YORK, NY - City Parks Foundation announced today the selection of 109 grants through two competitive funding opportunities - the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund and GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC. More than ever before, New Yorkers have come to rely on parks and open spaces, the most fundamentally democratic and accessible of public resources. Parks are critical to our city’s recovery and reopening – offering fresh air, recreation, and creativity - and a crucial part of New York’s equitable economic recovery and environmental resilience. These grant programs will help to support artists in hosting free, public performances and programs in parks, plazas, and gardens across NYC, along with the nonprofit organizations that help maintain many of our city’s open spaces. Both grant programs are administered by City Parks Foundation. The NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund will award nearly $2M via 64 grants to NYC-based small and medium-sized nonprofit organizations. Grants will help to support basic maintenance and operations within heavily-used parks and open spaces during a busy summer and fall with the city’s reopening. Notable projects supported by this fund include the Harlem Youth Gardener Program founded during summer 2020 through a collaboration between Friends of Morningside Park Inc., Friends of St. Nicholas Park, Marcus Garvey Park Alliance, & Jackie Robinson Park Conservancy to engage neighborhood youth ages 14-19 in paid horticulture along with the Bronx River Alliance’s EELS Youth Internship Program and Volunteer Program to invite thousands of Bronxites to participate in stewardship of the parks lining the river banks. -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

Gowanus Canal & Newtown Creek Superfund Sites: a Proposal

Gowanus Canal & Newtown Creek Superfund Sites: A Proposal by Larry Schnapf he federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2010 designated as fed eral superfund sites the entire length of T the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn and 3.8 miles of Newtown Creek on the border of Queens and Brooklyn. Property owners near these water bodies fear that EPA's action will lower property values and make it even more difficult to obtain loans and other wise develop their land. Many small businesses also fear that they may become responsible for paying a portion of the cleanup costs. The superfund process could take five to ten years to complete, during which time property owners will be faced with significant economic uncertainty. There is, however, a way tore lieve many of the smaller property owners by giving them an early release. Gowanus Canal Superfund Site The Gowanus Canal (Canal) runs for 1.8 miles through the Brooklyn residential neighborhoods of Gowanus, Park Slope, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens, TABLE CJF' CONTENTS and Red Hook. The adjacent waterfront is primarily commercial and industrial, currently consisting of Legislative Update ....................... 75 concrete plants, warehouses, and parking lots. At one CityRegs Update......................... 75 time Brooklyn Union Gas, the predecessor of National Decisions of Interest Grid, operated a large manufactured gas facility on Housing ............................ 76 the shores of the Canal. Affirmative Litigation ................. 77 EPA's initial investigation identified a variety of Human Rights ....................... 77 contaminants in the Canal's sediments including poly Health .............................. 79 cyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), volatile organ Audits & Reports ..................... 79 ic contaminants (VOCs), polychlorinated biphenyls Land Use ........................... -

Reel-It-In-Brooklyn

REEL IT IN! BROOKLYN Fish Consumption Education Project in Brooklyn ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: This research and outreach project was developed by Going Coastal, Inc. Team members included Gabriel Rand, Zhennya Slootskin and Barbara La Rocco. Volunteers were vital to the execution of the project at every stage, including volunteers from Pace University’s Center for Community Action and Research, volunteer translators Inessa Slootskin, Annie Hongjuan and Bella Moharreri, and video producer Dave Roberts. We acknowledge support from Brooklyn Borough President Marty Markowitz and funding from an Environmental Justice Research Impact Grant of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Photos by Zhennya Slootskin, Project Coordinator. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Study Area 3. Background 4. Methods 5. Results & Discussion 6. Conclusions 7. Outreach Appendix A: Survey List of Acronyms: CSO Combined Sewer Overflow DEC New York State Department of Environmental Conservation DEP New York City Department of Environmental Protection DOH New York State Department of Health DPR New York City Department of Parks & Recreation EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency GNRA Gateway National Recreation Area NOAA National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Agency OPRHP New York State Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation PCBs Polychlorinated biphenyls WIC Women, Infant and Children program Reel It In Brooklyn: Fish Consumption Education Project Page 2 of 68 Abstract Brooklyn is one of America’s largest and fastest growing multi‐ethnic coastal counties. All fish caught in the waters of New York Harbor are on mercury advisory. Brooklyn caught fish also contain PCBs, pesticides, heavy metals, many more contaminants. The waters surrounding Brooklyn serve as a source of recreation, transportation and, for some, food. -

New York City Area: Health Advice on Eating Fish You Catch

MAPS INSIDE NEW YORK CITY AREA Health Advice on Eating Fish You Catch 1 Why We Have Advisories Fishing is fun and fish are an important part of a healthy diet. Fish contain high quality protein, essential nutrients, healthy fish oils and are low in saturated fat. However, some fish contain chemicals at levels that may be harmful to health. To help people make healthier choices about which fish they eat, the New York State Department of Health issues advice about eating sportfish (fish you catch). The health advice about which fish to eat depends on: Where You Fish Fish from waters that are close to human activities and contamination sources are more likely to be contaminated than fish from remote marine waters. In the New York City area, fish from the Long Island Sound or the ocean are less contaminated. Who You Are Women of childbearing age (under 50) and children under 15 are advised to limit the kinds of fish they eat and how often they eat them. Women who eat highly contaminated fish and become pregnant may have an increased risk of having children who are slower to develop and learn. Chemicals may have a greater effect on the development of young children or unborn babies. Also, some chemicals may be passed on in mother’s milk. Women beyond their childbearing years and men may face fewer health risks from some chemicals. For that reason, the advice for women over age 50 and men over age 15 allows them to eat more kinds of sportfish and more often (see tables, pages 4 and 6). -

Coast Guard, DHS § 117.791

Coast Guard, DHS § 117.791 and half hour, except that commercial 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. to 7 p.m., Monday vessels shall be passed at any time. through Friday, except federal holi- From December 16 through March 31, days. the draw shall open on signal if at least (2) The draws of the Willis Avenue 12 hours notice is given. Bridge, mile 1.5, Third Avenue Bridge, mile 1.9, and the Madison Avenue [CGD 82–025, 49 FR 17452, Apr. 24, 1984, as amended by USCG–1999–5832, 64 FR 34712, Bridge, mile 2.3, need not open for the June 29, 1999; USCG–2008–0179, 73 FR 35013, passage of vessel traffic at various June 19, 2008] times between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m. on the first Sunday in May and November. § 117.787 Gowanus Canal. The exact time and date of each bridge The draws of the Ninth Street closure will be published in the Local Bridge, mile 1.4, the Third Street Notice to Mariners several weeks prior Bridge, mile 1.8, the Carroll Street to each closure. Bridge, mile 2.0, and the Union Street (c) The draw of the Metro North Bridge, mile 2.1, at Brooklyn, shall (Park Avenue) Bridge, mile 2.1, shall open on signal, if at least a two-hour open on signal, except, as provided in advance notice is given to the New paragraph (a) of this section, if at least York City Department of Transpor- a four-hour advance notice is given. tation (NYCDOT), Radio Hotline, or The draw need not open for the passage the NYCDOT Bridge Operations Office. -

Riverkeeper: Empowering Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek

CASE STUDY CHALLENGE Riverkeeper: Empowering Gowanus Canal • Raise awareness of the environmental issues related to the and Newtown Creek Communities to Prevent New York Harbor, call attention to the freshwater resources in the Stormwater Pollution region and educate the public Founded 50 years ago by a group of fishermen determined to reclaim the declining Hudson River from polluters, Riverkeeper has grown into the SOLUTION • Riverkeeper conducted a river’s most effective advocate. Riverkeeper’s vision is for clean, swimmable community-wide education effort waters, a Hudson River teeming with life, and safe and abundant drinking through a storm drain a stenciling water supplies. To reach their goals, Riverkeeper performs scientific research, initiative in the neighborhoods enforces environmental laws, advocates for legal protections, and organizes surrounding Gowanus Canal and and educates grassroots activists. Newtown Creek, working with four partners: the Gowanus Canal Challenge Conservancy (GCC), the Newtown As the most densely populated urban waterfront in the nation, New York Creek Alliance (NCA), the SWIM City’s waterways are plagued by toxics, sewage, garbage and debris. Each Coalition, and the and the New York City Soil and Water Conservation year, billions of gallons of polluted stormwater empty into waterways when it District rains – carrying the oils, contaminants, and garbage from our streets, parking lots, and industrial sites. Communities have an important role to play “street RESULTS level” in keeping their waterways clean by learning about wastewater systems • Partners NCA and GCC assessed and where their storm drains empty. Environmental justice communities are their neighborhoods and identified disproportionately impacted as they struggle for open space opportunities and lists of locations to map and stencil. -

CSO) Facility

Gowanus Canal Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) Facility ULURP Site Selection and Acquisition 180065 PCK Brooklyn Community Board 6 October 26, 2017 Overview . The Gowanus Canal was designated a Superfund site in 2010. The EPA has identified a number of potential responsible parties, including New York City and National Grid. The EPA has required the City to remediate chemical contaminants at the canal and reduce combined sewer overflows (CSOs) into the canal. Combined Sewer Overflow . NYC’s sewer system is approximately 60% combined, which means it is used to convey both sanitary and storm flows. When the sewer system is at full capacity, a diluted mixture of rain water and sewage can be released into local waterways. This is called a combined sewer overflow (CSO). Dry Weather Stormy Weather Conditions Conditions Down Down Spout Spout Catch Basin Catch Basin Building Sewer Building Sewer Connection Combined Connection Combined Sewer Outfall Sewer Outfall City Sewer Main City Sewer Main Sewer Sewer Regulator Regulator Gowanus Canal Sewershed Areas Ongoing Investment in Reducing CSO Project Description and Location Construct two underground CSO tanks and associated headhouses to intercept and store CSOs during wet weather events. Head End Facility 8 million gallon tank Owls Head Facility 4 million gallon tank ULURP Action • DEP is currently pursuing Site Selection & Acquisition of the Head End Site. • The application was certified into review September 18th, 2017. • A ULURP for demapping Douglass Street between Nevins Street and the Canal will follow. This action is not necessary to construct the facility, but it will clean up the City Map and the record. -

Gowanus Canal

Public Health Assessment Final Release GOWANUS CANAL CITY OF NEW YORK BOROUGH OF BROOKLYN KINGS COUNTY, NEW YORK EPA FACILITY ID: NYN000206222 Prepared by New York State Department of Health JANUARY 11, 2017 Prepared under a Cooperative Agreement with the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Division of Community Health Investigations Atlanta, Georgia 30333 THE ATSDR PUBLIC HEALTH ASSESSMENT: A NOTE OF EXPLANATION This Public Health Assessment was prepared by ATSDR’s Cooperative Agreement Partner pursuant to the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA or Superfund) section 104 (i)(6) (42 U.S.C. 9604 (i)(6)), and in accordance with our implementing regulations (42 C.F.R. Part 90). In preparing this document, ATSDR’s Cooperative Agreement Partner has collected relevant health data, environmental data, and community health concerns from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), state and local health and environmental agencies, the community, and potentially responsible parties, where appropriate. In addition, this document has previously been provided to EPA and the affected states in an initial release, as required by CERCLA section 104 (i)(6)(H) for their information and review. The revised document was released for a 30-day public comment period. Subsequent to the public comment period, ATSDR’s Cooperative Agreement Partner addressed all public comments and revised or appended the document as appropriate. The public health assessment has now been reissued. This concludes the public health assessment process for this site, unless additional information is obtained by ATSDR’s Cooperative Agreement Partner which, in the agency’s opinion, indicates a need to revise or append the conclusions previously issued. -

New York City Area: Health Advice on Eating the Fish You Catch

MAPS NEW YORK INSIDE CITY AREA Health Advice on Eating Fish You Catch 1 Why We Have Advisories Fishing is fun and fish are an important part of a healthy diet. Fish contain high quality protein, essential nutrients, healthy fish oils and are low in saturated fat. However, some fish contain chemicals at levels that may be harmful to health. To help people make healthier choices about which fish they eat, the New York State Department of Health issues advice about eating sportfish (fish you catch). The health advice about which fish to eat depends on: Where You Fish Fish from waters that are close to human activities and contamination sources are more likely to be contaminated than fish from remote marine waters. In the New York City area, fish from the Long Island Sound or the ocean are less contaminated. Who You Are Women of childbearing age (under 50) and children under 15 are advised to limit the kinds of fish they eat and how often they eat them. Women who eat highly contaminated fish and become pregnant may have an increased risk of having children who are slower to develop and learn. Chemicals may have a greater effect on the development of young children or unborn babies. Also, some chemicals may be passed on in mother’s milk. Women beyond their childbearing years and men may face fewer health risks from some chemicals. For that reason, the advice for women over age 50 and men over age 15 allows them to eat more kinds of sportfish and more often (see tables, pages 4 and 6).