Waders on Swansea Bay: Past Trends and Present Usage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Age-Related Differences in Ruddy Turnstone Foraging and Aggressive Behavior

AGE-RELATED DIFFERENCES IN RUDDY TURNSTONE FORAGING AND AGGRESSIVE BEHAVIOR SARAH GROVES ABSTRACT.--Theforaging behavior of fall migrant Ruddy Turnstoneswas studiedon the Mas- sachusettscoast on 2 different substrates,barnacle-covered rocks and sand and weed-litteredflats. Foragingrates differedsignificantly between the 2 substrates.On eachsubstrate the foragingand successrates of adults and juveniles differed significantly while the frequenciesof successwere similarfor both age-classes.The observeddifferences in foragingrates of adultsand juvenilesmay be due to the degreeof refinementof foragingtechniques. Experience in searchingfor and handling prey may be a primary factor accountingfor thesedifferences, and foragingperformance probably improves with age and experience.Alternatively, the differencesmay be due to the presenceof inefficient juveniles that do not survive to adulthood. Both adultsand juveniles in the tall-depressedposture were dominant in aggressiveinteractions much morefrequently than birds in the tall-levelposture. In mixedflocks of foragingadult and juvenile turnstones,the four possibletypes of aggressiveinteractions occurred nonrandomly. Adult over juvenile interactionsoccurred more frequently than expected,and juvenile over adult interac- tions were never seen.A tentative explanationof this phenomenonmay be that juveniles misinter- pret or respondambivalently to messagesconveyed behaviorally by adultsand thusbecome espe- cially vulnerableto aggressionby adults.The transiencyof migrantsmade it unfeasibleto evaluate -

Discover the Rhossili Bay Dylan Thomas Would Have Known

Discover the Rhossili Bay Dylan Thomas would have known visitswanseabay.com ‘I wish I was in schoolfriend Guido Heller ran the Worm’s Head Hotel, but at the time it Rhossili’… did not have a licence. …wrote poet and writer Dylan Thomas (when he was pining to be back home). More about Dylan And you can certainly see why; Rhossili Bay is, as Dylan also aptly put, a ‘very Many people are familiar with Dylan’s long golden beach’ on the Gower poetry and prose, some of which is Peninsula, which was the first in the influenced by Gower’s inspirational UK to be designated as an Area of countryside and coastal scenery; Outstanding Natural Beauty. but this summer, there is a unique opportunity to see some of Dylan’s A ‘VERY LONG GOLDEN personal letters and manuscripts, BEACH’ ON THE GOWER written in his own hand at an PENINSULA exceptional exhibition at Swansea’s Dylan Thomas Centre. Dylan Thomas spent his boyhood in Swansea and enjoyed camping on INFLUENCED BY Gower as depicted in his short story GOWER’S INSPIRATIONAL ‘Extraordinary Little Cough’. The COUNTRYSIDE AND COASTAL promontory of Worm’s Head is linked SCENERY to the mainland by a tidal causeway and Dylan was apt to mistime his return This exhibition is part of Dylan Thomas and get cut off by the tide – resulting 2014, a year-long celebration of his in an impromptu overnight stay on life and work in his hometown and the Worm! He writes about this in the surrounding area. story ‘Who Do You Wish Was With Us?’. -

Three Cliffs Bay Holiday Park

Ahoy there - it’s the Year of the Sea! y a B #S ea eaSwans Why #SeaSwanseaBay? Our past, present… and future is tied to the sea. From our Norse heritage and historic port, to our commitment to protecting our landscapes and wildlife – Gower was the first to be designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in the UK! So, whether you enjoy walking, surfing or our seafood – you’ll soon ‘sea’ how closely connected we are to the blue briny lapping at our shores – it’s even in our name Swansea Bay. visitswanseabay.com 2 Swansea Bay F3 Swansea Bay is just minutes away from the heart of the city centre. It’s also a Watersports Centre of Excellence. ∆QΩKL aKvW˙®X Beachcomber www.beachcomberguesthouse.com (01792 651380 Bracelet Bay F4 Just around Mumbles’ headland is the beautiful Bracelet Bay. Its rocky shoreline is award winning, and it’s great for ice cream. åΩKL aKv˙ LC Swansea www.thelcswansea.com (01792 466500 3 For key to symbols, see inside back cover Limeslade Bay F4 A small, sheltered cove, Limeslade Bay is a rugged and rocky retreat, that’s easy to get to. ΩKL aKv˙ Rotherslade Bay F4 Around the corner from Mumbles is Rotherslade Bay. It’s a small and sandy stretch, that’s easily accessible by road. KL aKv˙X Wales National Pool Swansea www.walesnationalpoolswansea.co.uk (01792 513513 Langland Bay E4 One for the family, Langland Bay offers a great range of facilities. Explorers can also enjoy a coastal clifftop walk. å∆QΩKL aKvW˙uX visitswanseabay.com 4 Caswell Bay E4 Caswell Bay is a sought-after spot with surfers and families alike. -

Population Analysis and Community Workshop for Far Eastern Curlew Conservation Action in Pantai Cemara, Desa Sungai Cemara – Jambi

POPULATION ANALYSIS AND COMMUNITY WORKSHOP FOR FAR EASTERN CURLEW CONSERVATION ACTION IN PANTAI CEMARA, DESA SUNGAI CEMARA – JAMBI Final Report Small Grant Fund of the EAAFP Far Eastern Curlew Task Force Iwan Febrianto, Cipto Dwi Handono & Ragil S. Rihadini Jambi, Indonesia 2019 The aim of this project are to Identify the condition of Far Eastern Curlew Population and the remaining potential sites for Far Eastern Curlew stopover in Sumatera, Indonesia and protect the remaining stopover sites for Far Eastern Curlew by educating the government, local people and community around the sites as the effort of reducing the threat of habitat degradation, habitat loss and human disturbance at stopover area. INTRODUCTION The Far Eastern Curlew (Numenius madagascariencis) is the largest shorebird in the world and is endemic to East Asian – Australian Flyway. It is one of the Endangered migratory shorebird with estimated global population at 38.000 individual, although a more recent update now estimates the population at 32.000 (Wetland International, 2015 in BirdLife International, 2017). An analysis of monitoring data collected from around Australia and New Zealand (Studds et al. in prep. In BirdLife International, 2017) suggests that the species has declined much more rapidly than was previously thought; with an annual rate of decline of 0.058 equating to a loss of 81.7% over three generations. Habitat loss occuring as a result of development is the most significant threat currently affecting migratory shorebird along the EAAF (Melville et al. 2016 in EAAFP 2017). Loss of habitat at critical stopover sites in the Yellow Sea is suspected to be the key threat to this species and given that it is restricted to East Asian - Australasian Flyway, the declines in the non-breeding are to be representative of the global population. -

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

Focus on West Cross T Cross

Tyˆ Agored Rhifyn 2 2015 Y cylchgrawn ar gyfer Tenantiaid a Les-ddeiliaid y Cyngor Open House The Magazine for Council Tenants and Leaseholders Issue 2 2015 RReettuurrnn AAddddrreessss: : CCiittyy aanndd CCoouunnttyy ooff SSwwaannsseeaa,, CCiivviicc CCeennttrree,, OOyysstteerrmmoouutthh RRooaadd,, SSwwaannsseeaa,, SSAA11 33SSN N CCyyffeeiirriiaadd ddyycchhwweellyydd: : Dinas a Sir Abertawe, Canolfan Ddinesig, Ffocws ar West Cross Dinas a Sir Abertawe, Canolfan Ddinesig, Focus on West Cross HHeeooll YYssttuummllllwwyynnaarrtthh,, AAbbeerrttaawwee,, SSAA11 33SSN N Gweler tudalen 1 am fwy o fanylion See page 1 for more details Os hoffech gael yr wybodaeth hon mewn fformat arall e.e. print bras, Braille, disg neu ddull arall, cysylltwch â'r Gwasanaethau Cwsmeriaid Tai 01792 635045 neu ewch i’n gwefan If you require this information in a different format eg large prin t, Braill e, disc or other, please contact http://www.abertawe.gov.uk/tai Housing Customer Services 01792 635045 or neu e-bostiwch [email protected] visit our website www.swansea.gov.uk/housing or email [email protected] k u . v o g . a e s n a w s @ g n i s u o h 5 1 0 2 2 e u s s I n e p O : e s u o H g n i s u o h / k u . v o g . a e s n a w s . w w Tyˆ Agored w Rhifyn 2 2015 Y cylchgrawn ar gyfer Tenantiaid a Les-ddeiliaid y Cyngor Croeso i . S S E R P O T ) 2 9 7 1 0 ( d e s a b a e s n a w S e r a s r e b m u n e n o h p e l e t l l A G N I O G F O E M I T T A T C E R R O C S Y tu I 0 0 5 2 0 4 ..................... -

Blackpill, Swansea Venue .Pages

Emmett Technique Practitioner Training Blackpill, Swansea, S.Wales More info: Tel: +44 (0) 7932 347 983 [email protected] www.emmett-uk.co.uk Please note : there will be very specific Covid Guidelines to follow during all future courses for as long as the pandemic is around. We will be using PPE and following strict cleaning regulations for the whole day. More details in these guidelines will be sent out when the application form is completed. Venue: The Vivian Hall, Mumbles Road Blackpill Swansea West Glamorgan SA3 5AS 1. Limited Parking is available at the venue and if you are unlucky, there is also Blackpill Car park nearby 2. We will be starting promptly at 9:00 and finish at approximately 5:00 on both days 3. Comfortable loose clothing. Please come prepared to shed outer layers. It is easier to see body landmarks on skin than through clothing. We will drape and make people comfortable.If this is not possible for you, then let me know and we can, of course, plan ways around this for you. Many female students feel comfortable in vest type tops - the ones with narrow straps and so you may be happy to organise this for yourself if you prefer. Although if extra ventilation is b- needed to be Covid safe, then wearing layers may be a good option. 4. Finger nails must be very short 5. Due to Covid restrictions, you will need to bring all drinks and food & cutlery with you. 6. If you are able to bring. Treatment couch it will need to be in good condition and also have a face hole or fce cradle. -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

The Following Is a List of Birds Seen Or Reported Around Vinalhaven Over the Past Twenty Years

The following is a list of birds seen or reported around Vinalhaven over the past twenty years. Common Loon (Gavia immer) Snipe (Gallinago gallinago) Red-throated Loon (Gavia stellata) Woodcock (Scolopax minor)N Red Necked Grebe Podiceps grisegena) Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres) Horned Grebe (Podiceps auritus) Purple Sandpiper (Calidris maritime) Pie- billed Grebe (Poilymbus podiceps)N? Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Yellow-nosed albatross (Diomedi chlororhynchos) Dunlin (Calidris alpina) Fulmar (Fulmarus glacialis) Sanderling (Calidris alba) Sooty Shearwater (Puffinus griseus) Semipalmated Sandpiper (Calidris pusilla) Greater Shearwater (Puffinus gravis) Western Sandpiper (Calidrs mauri) Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus) Least Sandpiper (Calsidris minuttla) Wilson’s Petrel (Oceanites oceanicus) White-rumped Sandpiper (Calidris fuscicollis) Leach’s Petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa)N Baird’s Snadpiper (Calidris bairdii) White Pelican (Pelecanus erthrorhynchos) Pectoral Sandpiper (Calidris melnotos) Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda) Gannet (Sula bassanus) Pomarine Jaeger (Stoecorarius pomarinus) Great Cormorant (Phalocrocorax carbo)N Parasitic Jaeger (Stercorarius parasiticus) Double -breasted cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus)N Little Gull (Larus minutus) Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) Laughing Gull (Larus atricilla)N Bittern (Botaurus lentiginosus) Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis) Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) Herring Gull (Larus argenatatusN Green Heron (Butorides -

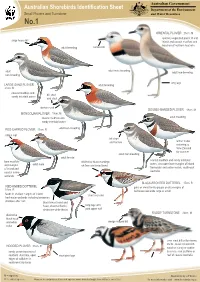

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

Bird Sightings January/February 1997 Summary

BIRD OBSERVER © Barry Van Dusen VOL. 25 NO. 3 JUNE 1997 BIRD OBSERVER • bimonthly journal • To enhance understanding, observation, and enjoyment of birds. Ma S S ^ VOL. 25, NO. 3 JUNE 1997 Editor in Chief Board of Directors Corporate Officers Matthew L. Pelikan Dorothy R. Atvidson President Associate Editor Marjorie W. Rines Alden G. Clayton Janet L. Heywood Treasurer & Clerk Department Heads William E. Davis, Jr. Glenn d’Entremont Assistant Clerk Cover Art H. Christian Floyd John A. Shetterly William E. Davis, Jr. Janet L. Heywood Where to Go Birding Subscription Manager Harriet E. Hoffman Jim Berry Carolyn Marsh Feature Articles Matthew L. Pelikan Advertisements Guy Washburn Marta Hersek Wayne R. Petersen Book Reviews Associate Staff John A. Shetterly Alden G. Clayton Theodore Atkinson Bird Sightings Robert H. Stymeist David E. Lange Robert H. Stymeist Patricia A. O’Neill Simon Perkins At a Glance Pamela A. Perry Wayne R. Petersen BIRD OBSERVER (USPS 369-850) is published bimonthly, COPYRIGHT © 1997 by Bird Observer of Eastern Massachusetts, Inc., 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178, a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation under section 501 (c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Gifts to Bird Observer will be greatly appreciated and are tax deductible. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to BIRD OBSERVER, 462 Trapelo Road, Belmont, MA 02178. PERIODICALS CLASS POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, MA. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $21 for 6 issues, $40 for two years in the U.S. Add $2.50 per year for Canada and foreign. Single copies $4.00. An Index to Volumes 1-11 is $3. Back issues: inquire as to price and availability. -

To Let,2 & 4 Newton Road, Mumbles, Swansea SA3

To Let Retail Retail Property 2 & 4 Newton Road, Mumbles, Swansea SA3 4AT • 233.74 Sq M (2,516 Sq Ft) • Prominent Corner Location • Sea Views from Upper Floors • May Suit Variety of Uses STPP Lambert Smith Hampton Axis 17 Axis Court, Mallard Way, Swansea Vale, Swansea SA7 0AJ T +44 (0)1792 702800 2 & 4 Newton Road, Mumbles, Swansea SA3 4AT Location Legal Costs Each party to be responsible for their own legal costs incurred in any transaction. Business Rates We have been advised that the property has a Rateable Value of £27,000. We recommend that interested parties rely on their own enquiries made with the local Rating Authority. Terms The property is available on a new Full Repairing and Insuring Lease at a rent of £39,000 per annum. Planning The property is situated in the village of Mumbles at the A2 Use. The property may be suitable for other uses, western end of Swansea Bay. The seaside village benefits subject to planning. from year round tourist trade. Local attractions include Oystermouth Castle, Mumbles Pier, Limeslade Bracelet Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) and Langland bays, as well as access to the Gower. An EPC has been commissioned and will be available upon request. Located on a prominent corner location at bottom end of Newton Road which benefits from high levels of footfall, Viewing and Further Information Newton Road is home to a mix of wine bars, Viewing strictly by prior appointment with the sole independent boutiques and national retailers including agent: Mountain Warehouse, Fat Face, Tesco & Joules. Other Alun Lewis Ed Cloke nearby occupiers include Pierre Bistro, Prezzo, La Parilla, Lambert Smith Hampton Lambert Smith Hampton Croeso Lounge and Costa.