The Lord's Table

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Going Political – Multimodal Metaphor Framings on a Cover of the Sports Newspaper a Bola

Going political – multimodal metaphor framings on a cover of the sports newspaper A Bola Maria Clotilde Almeida*1 Abstract This paper analyses a political-oriented multimodal metaphor on a cover of the sports newspaper A Bola, sequencing another study on multimodal metaphors deployed on the covers of the very same sports newspaper pertaining to the 2014 Football World Cup in Brazil (ALMEIDA/SOUsa, 2015) in the light of Forceville (2009, 2012). The fact that European politics is mapped onto football in multimodal metaphors on this sports newspaper cover draws on the interplay of conceptual metaphors, respectively in the visual mode and in the written mode. Furthermore, there is a relevant time-bound leitmotif which motivates the mapping of politics onto football in the sports newspaper A Bola, namely the upcoming football match between Portugal and Germany. In the multimodal framing of the story line under analysis. The visual mode apparently assumes preponderance, since a picture of Angela Merkel, a prominent leader of EU, is clearly overshadowed by a large picture of Cristiano Ronaldo, the captain of the Portuguese National Football team. However, the visual modality of Cristiano Ronaldo’s dominance over Angela Merkel is intertwined with the powerful metaphorical headline “Vamos expulsar a Alemanha do Euro” (“Let’s kick Germany out of the European Championship”), intended to boost the courage of the Portuguese national football team: “Go Portugal – you can win this time!”. Thus, differently from multimodal metaphors on other covers of the same newspaper, the visual modality in this case cannot be considered the dominant factor in multimodal meaning creation in this politically-oriented layout. -

Multimodal Metaphor Framings on a Cover of the Sports Newspaper a Bola

Going political – multimodal metaphor framings on a cover of the sports newspaper A Bola Maria Clotilde Almeida*1 Abstract This paper analyses a political-oriented multimodal metaphor on a cover of the sports newspaper A Bola, sequencing another study on multimodal metaphors deployed on the covers of the very same sports newspaper pertaining to the 2014 Football World Cup in Brazil (ALMEIDA/SOUsa, 2015) in the light of Forceville (2009, 2012). The fact that European politics is mapped onto football in multimodal metaphors on this sports newspaper cover draws on the interplay of conceptual metaphors, respectively in the visual mode and in the written mode. Furthermore, there is a relevant time-bound leitmotif which motivates the mapping of politics onto football in the sports newspaper A Bola, namely the upcoming football match between Portugal and Germany. In the multimodal framing of the story line under analysis. The visual mode apparently assumes preponderance, since a picture of Angela Merkel, a prominent leader of EU, is clearly overshadowed by a large picture of Cristiano Ronaldo, the captain of the Portuguese National Football team. However, the visual modality of Cristiano Ronaldo’s dominance over Angela Merkel is intertwined with the powerful metaphorical headline “Vamos expulsar a Alemanha do Euro” (“Let’s kick Germany out of the European Championship”), intended to boost the courage of the Portuguese national football team: “Go Portugal – you can win this time!”. Thus, differently from multimodal metaphors on other covers of the same newspaper, the visual modality in this case cannot be considered the dominant factor in multimodal meaning creation in this politically-oriented layout. -

Arte Y Comida En La Creación Contemporánea Desde Un Enfoque De Género

TESIS DOCTORAL ARTE Y COMIDA EN LA CREACIÓN CONTEMPORÁNEA DESDE UN ENFOQUE DE GÉNERO Doctoranda: María del Carmen Díaz Ruiz Directora: María Teresa Méndez Baiges Estudios Avanzados en Humanidades: Historia, Arte, Filosofía y Ciencias de la Antigüedad Facultad de Filosofía y Letras UNIVERSIDAD DE MÁLAGA, 2017 AUTOR: María del Carmen Díaz Ruiz http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2169-8415 EDITA: Publicaciones y Divulgación Científica. Universidad de Málaga Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial- SinObraDerivada 4.0 Internacional: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cualquier parte de esta obra se puede reproducir sin autorización pero con el reconocimiento y atribución de los autores. No se puede hacer uso comercial de la obra y no se puede alterar, transformar o hacer obras derivadas. Esta Tesis Doctoral está depositada en el Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad de Málaga (RIUMA): riuma.uma.es TESIS DOCTORAL ARTE Y COMIDA EN LA CREACIÓN CONTEMPORÁNEA DESDE UN ENFOQUE DE GÉNERO Doctoranda: María del Carmen Díaz Ruiz Directora: María Teresa Méndez Baiges Estudios Avanzados en Humanidades: Historia, Arte, Filosofía y Ciencias de la Antigüedad Facultad de Filosofía y Letras UNIVERSIDAD DE MÁLAGA, 2017 2 AGRADECIMIENTOS Las páginas que presento son el resultado de la investigación realizada durante los últimos cinco años. En este recorrido, la investigación se ha visto enriquecida por las aportaciones y consejos de personas como Beatriz Colomina, Estela Ocampo, Cecilia Novero y Lisl Hampton, sin cuyas contribuciones hubiera sido imposible. Me gustaría agradecer también a mis profesores por sus palabras llenas de sabiduría. Debo también agradecer a todas las personas de archivos y bibliotecas quienes me han ayudado y facilitado la labor de investigación, especialmente a Inmaculada Domínguez por su amabilidad durante tantos años. -

4. Application 1. Jesus Set up the Passover in Secret

Peter said to him, “Even though they all fall away, I will not.” And Jesus said to him, “Truly, I tell you, this very night, before the rooster crows twice, you will deny me three times.” But he said emphatically, “If I must die with you, I will not deny you.” And they all said the same. Mark 14:29–31 (ESV) Mark 14:12–31 — Jesus And Betrayal September 20, 2020 4. Application A. We will fail Jesus, but Jesus will never fail us. B. When the world is falling apart around us, God is in complete 1. Jesus set up the Passover in secret. control. He can even take sin and use it for his good purposes. And on the first day of Unleavened Bread, when they sacrificed the Passover lamb, his disciples said to him, “Where will you have us go and Life Group Questions prepare for you to eat the Passover?” Mark 14:12 (ESV) 1. Read Mark 14:12-31. How does the way Jesus sent the disciples to find the upper room give evidence that Jesus was in charge of the whole situation? And he sent two of his disciples and said to them, “Go into the city, and a 2. How does Jesus’ complete control of events surrounding his death man carrying a jar of water will meet you. Follow him, and wherever he encourage us when our life is falling apart? enters, say to the master of the house, ‘The Teacher says, Where is my guest room, where I may eat the Passover with my disciples?’ And he will 3. -

HOLY HOAXES: a BEAUTIFUL DECEPTION Celebrating William Voelkle’S Collecting Holy Hoaxes: Forgeries, Jokes, Conjurers’S Tricks and Illusions, Or Works of Art?

LES ENLUMINURES HOLY HOAXES: A BEAUTIFUL DECEPTION Celebrating William Voelkle’s collecting Holy Hoaxes: Forgeries, Jokes, Conjurers’s Tricks and Illusions, or Works of Art? Forgeries tell us much about any civilization. Look at what people are judgement. He says that she fixed him with an icy stare: “’Young man’,” forging, and we will learn what matters to them most. Christians of the she said, after briefly examining the manuscript, “’you have a splendid early Middle Ages were earnestly counterfeiting relics of saints, to create book there … Yes, a splendid example of the work of the Spanish Forg- tangible evidence of supernatural beliefs which they longed to validate. er’.” Even as the exchange is reported, we can detect her grudging ad- In twelfth-century Europe, people fabricated land charters, inventing miration of the artistry. The twist in that particular story is that she was documentation of title to feudal property on which livelihoods and soci- in this instance wrong: the manuscript (perhaps even to her disappoint- ety depended. In the sixteenth century, it was commonplace to concoct ment) was actually genuine. spurious ancestors, faking up complex family trees for the ambitious, in a time when social ranking was a necessity for advancement. Today, people No other manuscript custodian in the world has taken up this responsibil- forge works of art. This is the ultimate tribute to the place of art in our ity with more diligence and joy than William Voelkle. He is one of best lives, both as objects of beauty and as tokens of wealth. known and most widely liked curators the Morgan has ever had. -

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

Large Print Guide

The Waddesdon Bequest Funded by The Rothschild Foundation Contents Section 1 5 Section 2 9 Section 3a 13 Section 3b 27 Section 4a 43 Section 4b 61 Section 5a 75 Section 5b 91 Section 6a 101 Section 6b 103 Section 6c 107 Section 6d 113 Section 6e 119 Section 6f 123 Section 6g 129 Section 6h 135 Section 7a 141 Section 7b 145 Section 7c 149 Section 7d 151 Section 7e 153 Section 7f 157 Section 7g 163 Section 7h 169 Section 7i 173 Section 7j 179 Section 8 187 Entrance 8 2 3a 7j 1 7i 7h 3b 6a 7g 4a 6b 7f 6c 7e 6d 7d 4b 6e 7c 5a 6f 7b 6g 7a 6h 5b 4 Section 1 Entrance 8 2 3a 7j 1 7i 7h 3b 6a 7g 4a 6b 7f 6c 7e 6d 7d 4b 6e 7c 5a 6f 7b 6g 7a 6h 5b 5 The Waddesdon Bequest is a collection of outstanding quality generously bequeathed to the British Museum in 1898 by Baron Ferdinand Rothschild MP (1839–1898). It is a family collection, formed by a father and son: Baron Anselm von Rothschild (1803–1874) of Frankfurt and Vienna, and Baron Ferdinand, who became a British citizen in 1860, and a Trustee of the British Museum in 1896. Named after Baron Ferdinand’s Renaissance-style château, Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, the Bequest is a 19th-century recreation of a princely Kunstkammer or ‘art chamber’ of the Renaissance. The collection demonstrates how, within two generations, the Rothschilds expanded from Frankfurt to become Europe’s leading banking dynasty. -

CityGroup Discussion Guide

CITYGROUP DISCUSSION GUIDE Spring 2019 Week 10 – Mark 14:12-26 #CityGroupsTally Week of March 24, 2019 REMINDERS for leaders: ● Easter Reflections: We hope the Easter study guide has been helpful for you and your group. Would you ask your group members how they are liking what they are reading? Please let us know what feedback you are getting. ● In View of Multiplication: We have about 2 months left of group meetings for this semester. Have you been apprenticing anyone this semester? If not, now would be a good time to start by allowing them to help lead your group. ANNOUNCEMENTS: 1. Easter: Easter Sunday is April 21st. It will be here before we know it. Many people in our city are looking for a place to attend church on Easter. Would you make sure to invite someone this year? We will be passing our invite cards on Sundays soon. 2. Parent Commissioning: On Mother’s Day (Sunday, May 12th) we will have our next Parent Commissioning. See the “Kids” tab of the church website to sign up if needed. 3. Connect 101 & 201: We will be revising our Connect classes. We’re moving from 2 classes to one to help people get connected with the church. Stay tuned for details on dates and times. BIG IDEA: Jesus embraced God’s plan of suffering leading to salvation. PRAY: Ask the Lord to lead your group meeting, speak through the Scriptures and guide conversations. READ: Mark 14:12-26 HEAD (20 minutes) • WATCH THIS WEEK’S VIDEO 1) What do verses 12-16 teach us about Jesus’ relationship to the events surrounding his death? (See also 1 Peter 1:20 & Hebrews 12:2) He was in control and knew what awaited him. -

The Lord's Supper

THE LORD’S SUPPER A Readers Theatre for Five Voices © 1998 by Bette Dale Moore. All Rights Reserved. Use by Permission Only. Running Time: Approximately 8 minutes Theme: The sacrament of communion is steeped in symbolism and enriched by the knowledge and understanding of Jewish history and tradition. Scripture References: Mark 14 Synopsis: The origin and symbolism of the elements used in Communion are explained and explored in Readers Theatre style. Music for the Great Hallel is included for an optional arrangement of the hymn the Jesus and disciples may have sung at the conclusion of the Last Supper. The hymn has a distinctive Jewish sound and may be sung acappella in Gregorian chant style. Production Notes: Staging: Reader ONE stands S.R., a little removed from others. TWO and THREE stand C.S., FOUR and FIVE are S.L. Wireless lapels are preferable if amplification is necessary, although individual Microphone stands may also be used. Optional score for the “Great Hallel” in Gregorian Chant form is included at the end of script. The Hymn may be spoken or sung, depending on the abilities of the cast. The use of * indicates that the Reader should assume a different character, either through some sort of accent, or mannerism. The raised hand, tells the Reader to drop character and resume a normal speaking voice. For most of the reading, Reader ONE is the voice of Jesus; Readers TWO and THREE are two of His disciples. Cast: ONE—Male TWO—Male THREE—Male FOUR—Female FIVE—Female FIVE: In the fourteenth chapter of Mark’s Gospel, we read: FOUR: “On the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread, FIVE: when it was customary to sacrifice the Passover lamb, FOUR: Jesus’ disciples asked him, 1 * THREE (a disciple): “Where do you want us to go and make preparations for you to eat the Passover?” *TWO (another disciple): It’s getting close to the time, and I’m sure You realize there’s an awful lot to be done! THREE: Not that we’re worried or anything; TWO: we still have enough time to get it all done … THREE: . -

Knutsford Express Rolls Into Port Antonio

2 HOSPITALITY JAMAICA | WEDNESDAY, MAY 20, 2015 ADVERTISEMENT Knutsford Express rolls into Port Antonio Janet Silvera Hospitality Jamaica Coordinator NUTSFORD EXPRESS, the pioneering transportation Kfirm which has changed the face of local transport, has expanded its service to the forgotten tourist resort of Portland. Knutsford now boasts an island- wide network with new service along Jamaica’s north-east coast, from Ocho Rios to Port Antonio. The aim, Knutsford Express chief executive officer, Oliver Townsend said, is to put in 20,000 seats, giving properties that are struggling to get their guests there much-needed, reliable transportation, “particularly from Negril and Montego Bay”. Statistics from the Jamaica Tourist Board (JTB) shows a record of approximately 20,000 tourists visiting Port Antonio in 2014. “We are delighted after much effort to finally serve the parish of Portland,” said an excited Townsend during an interview with Hospitality Jamaica. He noted that from their new offices at the Anthony Copeland (left), director of operations, Knutsford Express, and the company’s managing director, Oliver Townsend. Errol Flynn Marina in Port Anto- nio, which opened on April 7, they Hotelier Jabbar Fahmi of Jamaica He explained that prospective for multi-destinations in the “They are all are air-conditioned are offering daily scheduled luxury Palace said, “Knutsford Express will passengers can plan a vacation in Caribbean, “Likewise, Jamaica with reclining seats, reading lights. coach service, “connecting our certainly speed up guest arrivals at Port Antonio because it’s no longer being diverse, you have this sub- They are a newer generation of award-winning north coast service Jamaica Palace. -

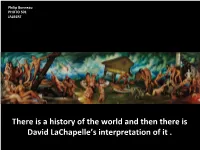

There Is a History of the World and Then There Is David Lachapelle's

Philip Bonneau PHOTO 501 JALBERT There is a history of the world and then there is David LaChapelle’s interpretation of it . Eminem: About to Blow, 1999 American Jesus: Archangel Michael Jackson, 2009 His works are often cited as hyper-real and slyly subversive. 1 He is known as a photographer and a director. As an artist and a photographer, but don’t ask him to differentiate between the two titles. They go hand in hand and he allows history to decide. 2 Cameron Diaz: Dollhouse Disaster, Home Invasion, 1997 Tupac Shakur for Details Magazine, April 1, 1996 “LaChapelle is without a doubt one of today’s most respected artists, whose style can be compared to no one. He has evolved his photography into an idiosyncratic and highly personal combination of reportage and surrealism.”3 Kayne West: Riot, 2006 Kayne West: The Cross I Bear, 2006 His work is considered “The highly polished, saturated and intricately composed photographs possess the surreal wildness of fever dreams, concocted as they are out of the imagery of celebrity, eroticism and modern Americana, and spiked with religious allegory and forebodings of doom.”5 He has been dubbed “The Fellini of Photography”. A title in honor of one of Italy’s most famous movie directors who “developed his own distinctive methods that superimposed dreamlike or hallucinatory imagery upon ordinary situations.”8 Helga LaChapelle, David LaChapelle He first began photography as a child where his mother often staged portraits for him to photograph with dogs that were not theirs and at homes they didn’t own. -

You Shall Know I AM – the Passover (The First Supper)

You Shall Know I AM: The Passover (The First Supper) (Exodus 11:1-13:16) Preached by Pastor Jason Tarn at HCC on October 14, 2018 Introduction ❖ When I conduct premarital counseling, one of the questions I like to ask during the session on parents and in-laws is for the couple to describe the first time they visited their future in- law’s home and shared a family meal. That meal can tell you so much about that family. ‣ We talk about what’s served for dinner because the food itself is a huge transmitter of customs and culture. But I also get them to think about how the conversation is carried. What do you talk about? Who does most of the talking? Are there any traditions like waiting for everyone to sit down and starting with a prayer (maybe even holding hands as you pray)? Are there any policies like no phones at the table or other distractions like a television playing? And how frequent are these kind of meals where everyone in the family is sitting down sharing it together? ❖ And in addition to family meals, I try to hone in on any ritual meals that are valued by the family. I'm talking about meals that are carry lots of meaning and tradition and are repeated and preserved by the family. Meals to celebrate a birthday or meals associated with a cherished holiday like Thanksgiving, Christmas, or New Years. These ritual meals are an important means of keeping family members connected by a shared tradition and making sure that tradition is passed down from generation to generation.