Bicycling to High Adventure.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economic Impact of Bicycling in the Central Shenandoah Valley

THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF BICYCLING IN THE CENTRAL SHENANDOAH VALLEY Bicycle tourism in the Central Shenandoah Valley region is estimated to have generated $8.6 million in sales activity in 2015. The total economic impact of bicycle tourism, including multiplier effects, is estimated to have been $13.6 million that supported 184 jobs in the region in 2015. August 12, 2016; Rev 1 THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF BICYCLING IN THE CENTRAL SHENANDOAH VALLEY An estimate of the economic impact of bicycle-related tourism and business in the Central Shenandoah Valley Public-Private Sponsors of the Study City of Harrisonburg Rockingham County Shenandoah County Greater Augusta Regional Tourism (GART) representing Augusta County, City of Staunton, and City of Waynesboro Lexington & the Rockbridge Area Tourism representing Rockbridge County, City of Buena Vista, and City of Lexington Shenandoah Valley Bicycle Coalition (SVBC) Bryce Resort Massanutten Resort This report was prepared by the Central Shenandoah Planning District Commission with the assistance of the study sponsors and the Roanoke Valley-Alleghany Regional Commission. Bicycling in the Central Shenandoah Valley Economic Impact Analysis TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... 2 1 Executive Summary.......................................................................................................... 3 2 Background .................................................................................................................... -

Travel Information Southwest Backpacking & Rock Climbing Outdoor Educator – 55 Days Course Number: CUQR-161 // 2.28.21 –

Travel Information Southwest Backpacking & Rock Climbing Outdoor Educator – 55 Days Course Number: CUQR-161 // 2.28.21 – 4.23.21 WHAT TO EXPECT FOR COURSE START MEETING PLACE & TIME 11:00am – 1:00pm MDT COBS Leadville Mountain Center 1930 Hwy 300 Leadville, CO 80461 Your course begins at Colorado Outward Bound School’s basecamp in Leadville, Colorado. This document includes helpful driving directions from the town of Leadville and a map of the campus below. We are requiring all students and families to drive themselves to course start, rather than traveling via public transportation such as plane, bus, or train. When you arrive, our staff will greet you in the lower parking lot wearing Colorado Outward Bound School T-shirts so they can be easily identified. Students can be provided with a lunch at 12:00pm. Due to procedures related to COVID-19, we cannot offer lunch to those dropping students off. If you are a student driving yourself, you will have secure parking on our basecamp for the entirety of your course. Because the course begins promptly at 1:00pm, everyone will need to finish eating by 1:00pm. Please arrive by 1:00pm so that our group can begin course activities as scheduled. Also, please make sure that your enrollment has been approved by your Course Advisor; students whose approval is unconfirmed cannot participate on the course. When you arrive please wear your mask. Staff will be doing health / symptom checks at course start to make sure everyone is healthy. Please be prepared to report any symptoms or exposures to staff. -

Orienteering at Brighton Woods

ORIENTEERING AT BRIGHTON WOODS • There are eight numbered posts (controls) for the orienteering course at Brighton Woods. Each has a number that corresponds to the number on the Brighton Woods Orienteering Map, but they may be found in any order. • It is easier to go directly from control to control when there is less ground cover: late fall, winter, and early spring. Long pants are recommended because of the poison ivy and ticks. 1. NUMBERED CONTROL DESCRIPTIONS 1. Sports Field 2. Southwest End of Pipeline Clearing 3. Amphitheater 4. The Bridge 5. Head of Trail 6. Rock Outcropping 7. River 8. Northeast End of Pipeline Clearing 2. PLOTTING THE COURSE • Find control #1 on the map.(The Sports Field.) • On the map, line up one edge of the compass from where you are (Control #1: Sports Field) to where you want to go, (Control # 2: Southwest End of Pipeline Clearing) making sure the direction-of-travel arrow faces your destination point. (This is the first secret of orienteering.) • Rotate the housing of the compassso that the gridlines are parallel to the North - South gridlines on the orienteering map. The cardinal point N must be at the North side of your map. (This is the second secret to orienteering.) • Readyour bearing in degrees at the Bearing Index. (At the Direction-of- Travel line, or the "Read Bearing Here" mark.) The number of degrees is * • Do not rotate the housing again until you need a new bearing! 3. FINDING THE FIXED CONTROLS • Stand directly in front of the control #1 and hold your compass level and squarely in front of your body. -

Introduction to Backcountry Hiking

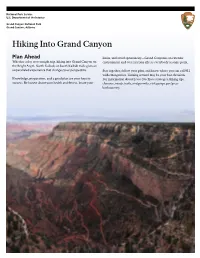

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon, Arizona Hiking Into Grand Canyon Plan Ahead limits, and avoid spontaneity—Grand Canyon is an extreme Whether a day or overnight trip, hiking into Grand Canyon on environment and overexertion affects everybody at some point. the Bright Angel, North Kaibab, or South Kaibab trails gives an unparalleled experience that changes your perspective. Stay together, follow your plan, and know where you can call 911 with emergencies. Turning around may be your best decision. Knowledge, preparation, and a good plan are your keys to For information about Leave No Trace strategies, hiking tips, success. Be honest about your health and fitness, know your closures, roads, trails, and permits, visit go.nps.gov/grca- backcountry. Warning While Hiking BALANCE FOOD AND WATER Hiking to the river and back in one • Do not force fluids. Drink water when day is not recommended due to you are thirsty, and stop when you are long distance, extreme temperature quenched. Over-hydration may lead to a changes, and an approximately 5,000- life-threatening electrolyte disorder called foot (1,500 m) elevation change each hyponatremia. way. RESTORE YOUR ENERGY If you think you have the fitness and • Eat double your normal intake of expertise to attempt this extremely carbohydrates and salty foods. Calories strenuous hike, please seek the advice play an important role in regulating body of a park ranger at the Backcountry temperature, and hiking suppresses your Information Center. appetite. TAKE CARE OF YOUR BODY Know how to rescue yourself. -

Guided Backpacking Trips a Wide Range of Options Exist for Guided Hiking at Grand Canyon National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Canyon Grand Canyon National Park Arizona Guided Backpacking Trips A wide range of options exist for guided hiking at Grand Canyon National Park. Please contact the companies directly regarding cost and services provided. All companies listed below are authorized to guide overnight hikes within the park. In addition, all guides are registered with the park and possess at a minimum a Wilderness First Responder and CPR certificate. If you would like to join a guided hiking and/or camping trip that is educational in nature; Grand Canyon Field Institute consider the Grand Canyon Field Institute (GCFI). GCFI works with the National Park Service to provide multi-day learning events that complement the park’s own interpretive programming. GCFI is the educational arm of the Grand Canyon Association, a non-profit organization established in 1932 to support education, research, and other programs for the benefit of Grand Canyon National Park and its visitors. Grand Canyon Field Institute 866-471-4435 www.grandcanyon.org/learn/grand-canyon-association-field-institute Backpacking Guide Services, April 2017 4Points Expeditions 805-320-7602 Callipygian Ventures, Inc., dba Lonner F. Holden www.4pointswildmed.com Fitpacking 415-847-5784 or 888-840-3440 781-773-1115 www.intothewildjourneys.com Adventure Life Inc www.fitpacking.com 702-321-3118 Pygmy Guides www.adventurelifeinc.com Camping Car USA, INC 877-279-4697 213-481-5930 www.pygmyguides.com Adventures in Good Company www.campingcarusa.com 410-435-1965 Rubicon Outdoors, dba Alpinehikers www.adventuresingoodcompany.com Canyonology Treks 928-778-0345 928-699-0134 www.rubiconoutdoors.com All-Star Grand Canyon Tours, Inc. -

Appalachian Trail Backpacking Adventure, Grayson Highlands (18 Miles) Wednesday, May 26 at 6PM Through Saturday, May 29 at 2PM, $350

Backpacking 201: Appalachian Trail Backpacking Adventure, Grayson Highlands (18 miles) Wednesday, May 26 at 6PM through Saturday, May 29 at 2PM, $350 Put your boots on America’s most famous scenic trail. This trek will take you to new heights in the Grayson Highlands where we will spend three nights on or near the Appalachian Trail and climb Mt. Rogers—Virginia’s highest peak. There are stunning views from the treeless balds and if we are lucky, we may catch a glimpse of the local herd of wild ponies. The hike will involve some rock scrambling and constant changes in elevation. Some previous backpacking experience recommended. Backpacks, tents, sleeping bags, pads, stove and cook sets available to borrow. Program fees include all equipment and camping permits. Meals are not included. Entry to Grayson Highlands State Park not included. Attendance at the pre-trip informational meeting is required (Wednesday, May 19, 6-8PM, Oak Openings Lodge). We will check and fit gear, talk about the trip, and answer any questions. Attendance is also required at the Backpacking 101: Are You Ready for the Trail? program (Thursday, April 1, 6-8PM, Blue Creek Conservation Area Sledding Hill). All participants and staff must wear masks and abide by proper social distancing guidelines for the duration of the program. Mask breaks are allowed when appropriate. Participants must bring their own masks. Because of the intense planning for this trip, 50% of the fee is considered a non-refundable deposit per the refund policy. If you need to cancel for any reason, please call Ashley Smith at 419-265- 2920. -

How to Go Backpacking By: Alyssa Lloyd

How to go Backpacking By: Alyssa Lloyd !1 Table of Contents What is Backpacking 3-4 Getting in Shape 5-6 Backpacking Gear 7-8 Where to go Backpacking 9-10 Safety While on the Trail 11-13 Backpacking Ethics 14-15 Glossary 16 Works Referenced 17 Common Core State Standards 18 U of I e-book Template 19 !2 What is Backpacking? Backpacking is an outdoor activity where someone hikes around the wilderness and carries gear in a backpack. !3 The backpacker will find a place next to a body of water to camp for the night. These trips last at least one night. If you are more serious about it then the trip can last for weeks or even months. Aneroid Lake is a tarn in Oregon located in the Eagle Cap Wilderness. !4 Getting in Shape If you are a first-time backpacker, you want to make sure you are in shape. Hiking for miles with a heavy pack on your back requires strength and stamina. !5 To prepare yourself to hit the trail take low- mileage hikes with a light pack. As the trip gets closer increase the mileage and weight. The fitter you are the better you will feel when you are on the trail. !6 Backpacking Gear Packing your backpack can be tricky. You want your pack to be as light as possible but there are necessities that you cannot go without. To have a successful trip you need food, shelter and clothes. !7 Make sure to have a water filter just in case you run out of water. -

Sample Itineraries for Bold & Gold Expeditions All Backpacking Trips

*Note: The itineraries given therein are intended to be a sample schedule of each type of trip. These may change due to circumstances such as weather and the skill level of participants. *SAMPLE ITINERARIES FOR BOLD & GOLD EXPEDITIONS ALL BACKPACKING TRIPS DAILY TRAVEL TIME Hiking mileage will vary from trip to trip, but groups will cover between 3-10 miles a day *SAMPLE ITINERARY Day 1: Arrive at base camp, gear check, safety briefing, lunch, shuttle to trail head campsite Days 2-4: Hike to new camping destination, explore around their campsite, cook dinner, enjoy team-building activities Day 3, 4 or 5: Layover Day: a chance to camp at the same spot 2 nights in a row. Day hiking, exploring the area, outdoor skills, games FOR 1-WEEK TRIPS: Day 6-7: Final backpacking day Day 8: Return to Basecamp in Seattle, unpack gear, closing circle FOR 2-WEEK TRIPS: Days 6-7: Participants continue to learn about each other through team-building activities and take turns being “leader of the day” on the trail Day 8: A staff member will meet the group at a front country campsite with a re-ration of food and supplies Days 9-13: Participants will take on more responsibility and leadership, practicing Leave No Trace principles, cooking meals for the group and navigating the terrain. There will be another layover day Day 14: Final backpacking day Day 15: Return to Basecamp in Seattle, unpack gear, closing circle 1 WEEK TRIPS: 2 WEEK TRIPS: • Backpacking & Fishing • American Alps • Backpacking & Yoga • Backpacking & Leadership • Beyond City Limits • Backpacks, Beaches & Boulders** • Call of the North Cascades • Backpacks & Kayaks*** • Cascade Challenge • Mountain & Music • Fierce & Fabulous • Powerful Gifts**** • Make A Scene: Art & Backpacking • Olympic Coastal Backpacking • Olympic Coastal Challenge • Poets & Peaks • She-Nannigans! *Note: The itineraries given therein are intended to be a sample schedule of each type of trip. -

Itinerary Overview Joshua Tree Backpacking & Rock Climbing

Itinerary Overview Joshua Tree Backpacking & Rock Climbing – 7 days In General – Outward Bound courses are designed to be challenging- physically, mentally, and emotionally. From pushing yourself physically on a sheer rock face, to persevering through extreme weather, to managing challenges that arise within your group, Outward Bound may be one of the hardest things you will ever do. Outward Bound philosophy maintains that by facing the challenges presented to you, you will emerge physically and mentally stronger with an increased mastery of expedition skills as well as a better understanding of your own capabilities. We think that the payoff is well worth the work, but you should be aware of what you’re getting into and excited about tackling the challenges. Arriving physically fit will enhance your experience and ability to do well on the course and ultimately allow you to take full advantage of the expedition. You don’t need to have previous rock climbing or backpacking experience. We will teach you skills you need to know—how to climb and belay safely as well as how to take care of yourself in the desert. Course Area Joshua Tree National Park – Joshua Tree is a well-known international climbing destination set against the backdrop of one of California’s most surreal desert landscapes. The park is a massive 800,000 acres, much of which is designated as “wilderness,” with approximately 5,000 established climbing routes. The federal government protected this unique region by designating it a National Monument in 1936 and then as a National Park in 1994. Two distinctly different deserts, the Sonoran and the Mojave, merge at a transition zone where one can see different species indicative of each desert ecosystem. -

Touring with a Toddler

STORY AND PHOTOS BY SANDY GREIG CHANGE MY DIAPER OUTSIDE TOURING WITH A TODDLER ilvio: Latin, meaning “belonging to the forest.” Silvio, National Park and day-hiked on the Appalachian Trail. His our son, was not conceived in the forest, but he first words were “dirt” and “bike.” spent his first couple of days there as a zygote — the At this point, you might be wondering, what does this White Mountains, to be exact. We found out my have to do with cycling? Well, we were just buying time partner Amy was pregnant on our way to a six-day until he reached his first birthday — when he could finally backpacking trip to the Appalachian Trail in New wear a helmet! Diane Lees, from Hubbub Custom Bicycles SHampshire. We lasted about three days before we decided in Chesterland, Ohio, said we had to wait until then before we had spent too much money trying to get pregnant to risk he could be pulled in a bike trailer. After some extensive it hiking in the rain and sleeping on cold dirt. We ended our research, we decided on the Thule Chariot Cougar 2. We trip early. Jake, the dog, could not have been happier. With bought the double in hopes that Silvio would have a brother no Internet and a couple of AAA guidebooks, we ended up in or sister. It didn’t turn out that way, and we are blessed with Jasper, Maine, and day-hiked Acacia National Park. Silvio, the one outstanding son, who is quite happy that he can bring all zygote, would be happy here for the week. -

Bursting the Backpacker Bubble: Exploring Backpacking Ideology, Practices, and Contradictions

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones December 2016 Bursting the Backpacker Bubble: Exploring Backpacking Ideology, Practices, and Contradictions Mark J. Salvaggio University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Sociology Commons Repository Citation Salvaggio, Mark J., "Bursting the Backpacker Bubble: Exploring Backpacking Ideology, Practices, and Contradictions" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2900. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/10083212 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BURSTING THE BACKPACKER BUBBLE: EXPLORING BACKPACKING IDEOLOGY, PRACTICES, AND CONTRADICTIONS By Mark J. Salvaggio Bachelor of Science – Business Administration California State University, Bakersfield 2002 Master of Arts – Sociology California State University, Bakersfield 2007 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy – Sociology Department of Sociology College of Liberal Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2016 Copyright 2016 by Mark J. -

Hiking and Backpacking

Welcome to the Wayne The Athens District of the Wayne National Forest Contact Us (NF) has 14 trails open to hikers and backpackers. Hikers generally share these trails with other users. A detailed topographic map of our Trails are on both the Athens and Marietta units of hiking trails is available at our offices. the Athens District. Terrain on these trail systems Wayne National Forest varies from rolling hills and level ridgetops to some The Wayne National Forest has three offices very challenging hills and steep slopes. to serve visitors. Two are on the Athens Dis- Hiking and Depending upon the trail you choose to hike, you trict, one between Athens and Nelsonville, may encounter off-highway vehicles (OHVs), horses, and the other in Marietta. Office hours are or mountain bikes. Many trails intersect roads. Be 8 - 4:30 Monday through Friday. Backpacking mindful of traffic. If you bring your dog, it should on the be on a leash. Also use caution during hunting sea- Athens Ranger District sons. Blaze orange clothing is recommended during 13700 U.S. Hwy 33 Athens Ranger District deer gun seasons. Nelsonville, OH 45764 Phone: 740-753-0101 Trail use by OHVs, mountain bikes, and horses is prohibited from 12/16 through 4/14. Trail permits Marietta Unit Office are required for these three uses of Wayne trails. 27515 State Route 7 Hiking is allowed on all trails even if the trail is Marietta, OH 45750 closed to others users. Phone: 740-373-9055 Many areas of the Wayne do not have cell phone coverage.