Non-Lawyer Navigators in State Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resource Collection for High Ability Secondary Learners 2011

Resource Collection for High Ability Secondary Learners Office of Gifted Education Montgomery County Public Schools 2011 - 2012 Table of Contents 2011 – 2012 Materials for High Ability Secondary Students How to Order .................................................................................................................................. 3 Professional Resources for Teachers .............................................................................................. 4 Differentiation ............................................................................................................................. 4 Assessment .................................................................................................................................. 5 Learning Styles and Multiple Intelligences ................................................................................ 6 Curriculum, Strategies and Techniques ...................................................................................... 7 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................................................. 9 English ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Mathematics .............................................................................................................................. 13 History...................................................................................................................................... -

19680011654.Pdf

NASA TECHNICAL NOTE -NASA TN-- D-4449 c. 1 o* w d nP z c e r/l e z LOAN COPY: RETURN TO AFWL IWLIL-2) KIRTLAND AFB, N MU( NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION WASHINGTON, D. C. APRIL 1968 ~ TECH LIBRARY KAFB, NM Iillllllllllllll llllllllll lllllllllllllllll NAVIGATOR PERFORMANCE STUDIES FOR SPACE NAVIGATION USING THE NASA CV-990 RESEARCH AIRCRAFT By Richard A. Acken and Donald W. Smith Ames Research Center Moffett Field, Calif. NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION - For sole by the Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information Springfield, Virginia 22151 - CFSTI price $3.00 NAVIGATOR PERFORMANCE STUDES FOR SPACE NAVIGATION USING THE NASA CV-990 RESEARCH AIRCRAFT By Richard A. Acken and Donald W. Smith Ames Research Center Manually operated hand-held sextants are being studied at Ames Research Center to determine whether they are sufficiently accurate for midcourse navigation phases of manned space flight. Studies carried out on the ground have been extended by using the NASA CV-990 aircraft to provide sighting con- ditions closely simulating those in spacecraft and to investigate firther the measurement error due to lunar irradiance. The results of approximately 1200 measurements made during nine flights confirm results of simulator and ground- based studies which indicate that, with a hand-held sextant, an astronaut can be expected to make navigational measurements with errors having a standard deviation of approximately 210 arc seconds. A value for moon irradiance effect of approximately 25 arc seconds was established for the conditions of the experiment using a hand-held sextant. INTRODUCTION The manually operated hand-held sextant has provided marine navigators with a compact, lightweight, easily operated instrument for centuries. -

SPRING Nav-06.Indd

SPRING 2006 AUXILIARY LAYS WREATH VOL. 33, NO. 1 AT NATIONAL CEMETERY ® s Last November, the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary was granted the rare privilege of laying a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns in Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. The honor of actually laying the wreath was bestowed upon Joe Lifesaver Volunteer America’s Stern, IPDCP-11 D1SR, (second from left), who received permission from Arlington National Cemetary to perform the ceremony. A U.S. Marine Corps veteran and former Korean War POW, Stern commented, “This was one of the greatest honors I ever had.” Joining him at the ceremony are Gail Venezio, DDO; Tom Venezio, VCO; and Manuel Padilla, FC 11-11 all D1SR. Photo by Burt Hurvich, D-AA and DSO-PA 1SR. AMERICA’S Coast Guard Auxiliary Association, Inc. NON-PROFIT WATERWAY WATCH The Auxiliary Center U.S. POSTAGE PAID PERMIT NO. 842 9449 Watson Industrial Park JACKSONVILLE, FL. IN ACTION! St. Louis, MO 63126 Address service requested AST G CO U . S E M P E R A AUXILIARY GUARD COAST STATES UNITED S R . D U S P A A R A T U U Y XILIA R Spring 2006 Navigator 1 Auxiliary Artist Accepted AST G CO U . S E M P E R A S R . D U S P A A R A T U U Y XILIA R Contents SPRING 2006 VOL. 33, NO. 1 3 Rare Medal awarded to NY Auxiliarist 5 Dogs Learning to Fly 6 COMO Seibert 8 NACON 2006 is set 11 Interpreter asked to help on Midway 12 Color Guard launches dedication ceremonies 37 2006-07 13 U.S.-Canada RBS Initiatives EDITION 14 In Memoriam DEADLINES FALL 17 Auxiliary Wins NWSC and AFRAS awards AUGUST 15 18 USCG Rear Admiral and CGAUX WINTER Division Captain Cross Paths NOVEMBER 15 SPRING 20 Auxiliary Training Saves the Day FEBRUARY 15, 2007 23 New Requirements Cape Cod Jayhawk About to Embark on Katrina Rescue. -

A Characteristic of a Navigator's Situation Awareness for Crossing Ships

the International Journal Volume 11 on Marine Navigation Number 2 http://www.transnav.eu and Safety of Sea Transportation June 2017 DOI: 10.12716/1001.11.02.12 A Characteristic of a Navigator's Situation Awareness for Crossing Ships C. Nishizaki, T. Takemoto & Y. Kunieda Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, Tokyo, Japan ABSTRACT: Many ship collisions have been caused by a navigator’s error in the situation awareness (SA) of the navigator. In congested sea areas, navigators classify ships on the basis of different priority levels. For safety measures against ship collision, it is imperative for navigators to recognize the ships with high priority levels. In previous study, navigators’ SA was measured in a ship maneuvering simulator using the Situation Awareness Global Assessment Technique (SAGAT). From the results of the previous study, we proposed a new risk category, named as “attention area,” that covers ships with high priority level in the SA of navigators. However, the extent of data for navigators’ SA was limited. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to confirm the validity of the category using additional data of navigators SA. In this study, the validity of the proposed category was confirmed, and a limit line surrounding ships with high priority levels was identified. In addition, it was evident that the category was able to detect ships with high priority level around the time when the collision avoidance was performed. 1 INTRODUCTION maneuvering simulator, the possibility that trainees’ navigation skills could be measured by SAGAT was Many marine accidents are caused by errors on the indicated (Okazaki & Ohya 2012). -

Stone Spring Free

FREE STONE SPRING PDF Stephen Baxter | 528 pages | 10 Feb 2011 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780575089204 | English | London, United Kingdom Stone Spring - Wikipedia Alternate history at its most mindblowing-from the national bestselling author of Flood and Ark. Ten thousand years ago, a vast and fertile plain Stone Spring linking the British Stone Spring to Europe. Home to a tribe of simple hunter-gatherers, Northland teems with nature's bounty, but is also Stone Spring to its whims. Fourteen-year-old Ana calls Northland home, but her world is changing. The air is warming, the ice is melting, and the seas are rising. Then Ana meets a traveler from a far-dista. Then Ana meets a traveler from a far-distant city called Jericho-a city that is protected by a wall. And she starts to imagine the impossible Praise for Stephen Baxter and Stone Spring. Stephen Baxter Stone Spring born in Liverpool, England, in He holds degrees in mathematics, from Cambridge University; engineering, from Southampton University; and business administration, from Henley Management College. His first professionally published short story appeared in He has also published over sf short stories, several of which have won prizes. Goodreads helps you keep track Stone Spring books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Stone Spring by Stephen Baxter. Stone Spring Northland 1 by Stephen Baxter. -

A Selection of New Arrivals September 2017

A selection of new arrivals September 2017 Rare and important books & manuscripts in science and medicine, by Christian Westergaard. Flæsketorvet 68 – 1711 København V – Denmark Cell: (+45)27628014 www.sophiararebooks.com AMPERE, Andre-Marie. Mémoire. INSCRIBED BY AMPÈRE TO FARADAY AMPÈRE, André-Marie. Mémoire sur l’action mutuelle d’un conducteur voltaïque et d’un aimant. Offprint from Nouveaux Mémoires de l’Académie royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Bruxelles, tome IV, 1827. Bound with 18 other pamphlets (listed below). [Colophon:] Brussels: Hayez, Imprimeur de l’Académie Royale, 1827. $38,000 4to (265 x 205 mm). Contemporary quarter-cloth and plain boards (very worn and broken, with most of the spine missing), entirely unrestored. Preserved in a custom cloth box. First edition of the very rare offprint, with the most desirable imaginable provenance: this copy is inscribed by Ampère to Michael Faraday. It thus links the two great founders of electromagnetism, following its discovery by Hans Christian Oersted (1777-1851) in April 1820. The discovery by Ampère (1775-1836), late in the same year, of the force acting between current-carrying conductors was followed a year later by Faraday’s (1791-1867) first great discovery, that of electromagnetic rotation, the first conversion of electrical into mechanical energy. This development was a challenge to Ampère’s mathematically formulated explanation of electromagnetism as a manifestation of currents of electrical fluids surrounding ‘electrodynamic’ molecules; indeed, Faraday directly criticised Ampère’s theory, preferring his own explanation in terms of ‘lines of force’ (which had to wait for James Clerk Maxwell (1831-79) for a precise mathematical formulation). -

Towards a Co-Creative Encounter with the Book by Cameron Martin

Gone Critical— Towards a Co-Creative Encounter with the Book by Cameron Martin Reid A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2010 ©Cameron Martin Reid 2010 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation follows two interrelated lines of inquiry. The first, I formulate as follows: (1) How, historically speaking, has the discourse of literary criticism thought the book? How has it represented the book? Used the book? Put simply, what has the book become in the hands of the critic? Though, of course, answers to such questions will vary widely—especially as they intersect with related matters concerning the critic, herself, and what Henry Sussman refers to as the perceived ―task of the critic‖—it is my contention that the discourse of literary criticism remains unified by its inability to extricate itself from what I call the transcendent orientation to literature: an orientation that has both ancient and modern coordinates. In Part 1 of the dissertation, I map criticism‘s ongoing historical affair with transcendence—an affair that begins as far back as the Platonic dialogues, but that can be traced right up through the twentieth century, in and through the work of any number of critics, and many prominent schools of literary critical thought. -

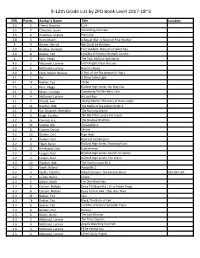

9-12Th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3

9-12th Grade List by ZPD Book Level 2017-18~3 ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 3.2 5 Friend, Natasha Lush 3.5 7 Colasanti, Susan Something Like Fate 3.5 6 Hamilton, Virginia Plain City 3.8 3 Harry Mazer A Boy at War: A Novel of Pearl Harbor 4 4 Barnes, Derrick We Could be Brothers 4.0 5 Bradley, Kimberly For Freedom: Story of a French Spy 4.0 8 Dekker, Ted Lost Bks of History Series#5: Lunatic 4 3 Kern, Peggy The Test, Bluford High Series 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Until Angels Close my Eyes 4.0 5 McDaniel, Lurlene Heart to Heart 4.0 4 Peck, Robert Newton A Part of the Sky (sequel to Pigs ) 4.1 5 Avi A Place Called Ugly 4.1 14 Dekker, Ted Thr3e 4.1 3 Kern, Peggy Bluford High Series: No Way Out 4.1 4 Mazer, Lerangis Somebody Tell Me Who I Am 4.1 4 McDaniel, Lurlene Hit and Run 4.1 7 Rinaldi, Ann Taking Liberty: The Story of Oney Judge 4.1 12 Riordan, Rick The Battle of the Labyrinth Bk 4 4.1 9 Van Draanen, Wendelin The Running Dream 4.1 9 Voigt, Cynthia Tell Me if the Lovers are Losers 4.2 6 Cannon, A.E. The Shadow Brothers 4.2 13 Condie, Ally Crossed Bk 2 4.2 8 Cooner, Donna Skinny 4.2 10 Deuker, Carl High Heat 4.2 8 Deuker, Carl Heart of a Champion 4.2 4 Folan, Karyn Bluford High Series: Breaking Point 4.2 12 Honeyman, Kay Interference 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: Search for Safety 4.2 3 Langan, Paul Bluford High Series: The Fallen 4.2 10 Riordan, Rick The Titan’s Curse Bk 3 4.2 10 Smith, Roland Above Bk 2 4.2 5 Yeatts, Tabatha Albert Einstein: The Miracle Mind 530.092 YEA 4.2 6 Lo'pez, Diana Choke 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For -

THE NAVIGATOR: Your Guide to Leadership for Social Purpose

THE CHANGE COLLECTION THE NAVIGATOR: your guide to leadership for social purpose Proudly supported by © Centre for Social Impact May 2017 THE NAVIGATOR: Your guide to social purpose leadership is generously supported by: The Centre for Social Impact believes we need effective leadership in our social purpose ecosystem to catalyse change for a better world. We believe that it doesn't matter where you work in the organisation; everyone has a role to play in creating positive social change. This means that leadership is shared by everyone. The Navigator is here to provide different ways of understanding leadership across your system, your organisation and the self so that you can find own path to practicing effective leadership. Find out more at www.csi.edu.au THE CHANGE COLLECTION The purpose of The Change Collection is to build the capacity of everyone working towards a more effective social impact system. The collection provides the foundation knowledge and tools for social change. THE CHANGE COLLECTION INCLUDES: • The Compass: your guide to social impact measurement • The Travel Companion: your guide to working with others for social outcomes • Orienting Your Journey: an approach for indicator assessment and selection • The Navigator: Your guide to leadership for social purpose Learn more about The Change Collection at: www.csi.edu.au/changecollection/ AUTHORS Alexandra Walker, Tracy Wilcox, Abigail Powell, Kristy Muir SUGGESTED CITATION Walker, A., Wilcox. T., Powell, A., and Muir, K. (2017) The Navigator: Your guide to leadership for social purpose. Sydney, Australia: The Centre for Social Impact ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank Macquarie Group Foundation for funding this work and members of the reference group for their advice and guidance on the development of The Navigator: Lauren O’Shaughnessy, Macquarie Group Foundation; Cameron Kerr, Taronga Conservation Society; Doug Taylor, Uniting; Sam Refshauge, batyr; Jayne Meyer-Tucker, JMT inc; and Peter Kaldor, New River Leadership. -

Navigator Grantee Summaries

2015 Navigator Grant Recipients Navigators serve as an in-person resource for Americans who want additional assistance when shopping for and enrolling in plans through the Health Insurance Marketplace. Below are the recipients of the 2015 Navigator grants in Federally-facilitated Marketplaces and State Partnership Marketplaces, grouped by state. The tables below provide information regarding which counties the grantee will serve and their target populations (as included in their grant application). As a reminder, Navigators are required to assist any consumer seeking assistance, even if that consumer is not a member of the community(ies) or groups the applicant expects to serve as outlined in their funding proposal. If applicable, the tables include information on subgrantee/subrecipient organization(s). Recipients marked with an asterisk (*) are operating in more than one state. The anticipated grant amount listed in each case only applies to the amount awarded that organization for that state’s specific operations during the first 12 months of the grant project period. The 2015 Navigator grants are being awarded for a three year (36 month) project period, which runs through September 1, 2018. ALABAMA AIDS Alabama, Inc. Anticipated grant amount: $777,923 Primary Contact: Sonja Smith Phone: 205-382-0242 Email: [email protected] Counties Served Target Population Subgrantee/Subrecipient Organizations Statewide • Populations that are newly- • Thrive Alabama, Cooper eligible for health insurance Green Mercy Health through the Affordable -

Book Title Author Reading Level Approx. Grade Level

Approx. Reading Book Title Author Grade Level Level Anno's Counting Book Anno, Mitsumasa A 0.25 Count and See Hoban, Tana A 0.25 Dig, Dig Wood, Leslie A 0.25 Do You Want To Be My Friend? Carle, Eric A 0.25 Flowers Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Growing Colors McMillan, Bruce A 0.25 In My Garden McLean, Moria A 0.25 Look What I Can Do Aruego, Jose A 0.25 What Do Insects Do? Canizares, S.& Chanko,P A 0.25 What Has Wheels? Hoenecke, Karen A 0.25 Cat on the Mat Wildsmith, Brain B 0.5 Getting There Young B 0.5 Hats Around the World Charlesworth, Liza B 0.5 Have you Seen My Cat? Carle, Eric B 0.5 Have you seen my Duckling? Tafuri, Nancy/Greenwillow B 0.5 Here's Skipper Salem, Llynn & Stewart,J B 0.5 How Many Fish? Cohen, Caron Lee B 0.5 I Can Write, Can You? Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 Look, Look, Look Hoban, Tana B 0.5 Mommy, Where are You? Ziefert & Boon B 0.5 Runaway Monkey Stewart, J & Salem,L B 0.5 So Can I Facklam, Margery B 0.5 Sunburn Prokopchak, Ann B 0.5 Two Points Kennedy,J. & Eaton,A B 0.5 Who Lives in a Tree? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Who Lives in the Arctic? Canizares, Susan et al B 0.5 Apple Bird Wildsmith, Brain C 1 Apples Williams, Deborah C 1 Bears Kalman, Bobbie C 1 Big Long Animal Song Artwell, Mike C 1 Brown Bear, Brown Bear What Do You See? Martin, Bill C 1 Found online, 7/20/2012, http://home.comcast.net/~ngiansante/ Approx. -

2011 Navigator Owners Guide

Table of Contents Introduction 4 Instrument Cluster 12 Warning lights and chimes 12 Gauges 18 Message center 20 Entertainment Systems 30 AM/FM stereo with CDX6/MP3 30 Auxiliary input jack (Line in) 36 USB port 38 Rear seat controls 39 Satellite radio information 44 Navigation system 47 SYNC 47 Climate Controls 48 Dual automatic temperature control 48 Rear window defroster 54 Lights 55 Headlamps 55 Turn signal control 58 Bulb replacement 60 Driver Controls 65 Windshield wiper/washer control 65 Steering wheel adjustment 67 Power windows 73 Mirrors 75 Speed control 80 Moon roof 83 1 2011 Navigator (nav) Owners Guide, 1st Printing USA (fus) Table of Contents Locks and Security 97 Keys 97 Locks 103 Anti-theft system 114 Seating and Safety Restraints 120 Seating 120 Safety restraints 138 Airbags 152 Child restraints 162 Tires, Wheels and Loading 181 Tire information 183 Tire inflation 186 Tire Pressure Monitoring System (TPMS) 198 Vehicle loading 202 Trailer towing 210 Recreational towing 216 Driving 217 Starting 217 Brakes 223 AdvanceTrac 226 Air suspension 232 Transmission operation 235 Forward and reverse sensing system 238 Rear-view camera system 241 Roadside Emergencies 253 Getting roadside assistance 253 Hazard flasher control 254 Fuel pump shut-off switch 255 Fuses and relays 256 Changing tires 264 Wheel lug nut torque 272 Jump starting 274 Wrecker towing 277 2 2011 Navigator (nav) Owners Guide, 1st Printing USA (fus) Table of Contents Customer Assistance 279 Reporting safety defects (U.S. only) 286 Reporting safety defects (Canada only) 286 Cleaning 287 Maintenance and Specifications 295 Engine compartment 297 Engine oil 300 Battery 303 Engine coolant 305 Fuel information 311 Air filter(s) 325 Part numbers 330 Maintenance product specifications and capacities 331 Engine data 334 Accessories 338 Ford Extended Service Plan 340 Scheduled Maintenance Guide 344 Normal scheduled maintenance and log 348 Index 364 All rights reserved.