Book Review: the Mathematics of Juggling, Volume 51, Number 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BENEFITS of LEARNING to JUGGLE for CHILDREN Written by Dave Finnigan

THE BENEFITS OF LEARNING TO JUGGLE FOR CHILDREN Written by Dave Finnigan Fitness, Motor Skills, Rhythm, Balance, Coordination Benefits . Students can start acquiring pre-juggling skills in pre-school and kindergarten by learning to toss and catch one big, colorful, slow-moving nylon scarf. Once tossing and catching becomes routine, you can use one nylon scarf anywhere that you would normally use a ball or beanbag for most games and many individual challenges. Just think of the scarf as a "ball with training wheels." Scarf juggling and scarf play progresses in a step-by-step manner from one, to two, and on to three. Scarf play and scarf juggling requires big, flowing movements. Children get a great cardio-vascular and pulmonary work-out when they juggle scarves, exercising the big muscles close to the head and close to the heart. They will find scarf juggling to be a great deal of work and lots of fun at the same time. Once they move on to beanbags or other faster moving equipment, they get exercise not only from tossing, but from bending over to pick up errant objects as well. Once a student can juggle continuously, they can "workout" with heavy or bulky objects such as heavyweight beanbags, basketballs, or other items which provide strenuous exercise while they improve focus and dexterity. Because all of this tossing and catching activity can be done to music, you can use different types of music to help children acquire a sense of rhythm and a natural "beat." By working together, students can participate in a group activity requiring concentration and attention to task and reinforcing rhythm. -

The Beginner's Guide to Circus and Street Theatre

The Beginner’s Guide to Circus and Street Theatre www.premierecircus.com Circus Terms Aerial: acts which take place on apparatus which hang from above, such as silks, trapeze, Spanish web, corde lisse, and aerial hoop. Trapeze- An aerial apparatus with a bar, Silks or Tissu- The artist suspended by ropes. Our climbs, wraps, rotates and double static trapeze acts drops within a piece of involve two performers on fabric that is draped from the one trapeze, in which the ceiling, exhibiting pure they perform a wide strength and grace with a range of movements good measure of dramatic including balances, drops, twists and falls. hangs and strength and flexibility manoeuvres on the trapeze bar and in the ropes supporting the trapeze. Spanish web/ Web- An aerialist is suspended high above on Corde Lisse- Literally a single rope, meaning “Smooth Rope”, while spinning Corde Lisse is a single at high speed length of rope hanging from ankle or from above, which the wrist. This aerialist wraps around extreme act is their body to hang, drop dynamic and and slide. mesmerising. The rope is spun by another person, who remains on the ground holding the bottom of the rope. Rigging- A system for hanging aerial equipment. REMEMBER Aerial Hoop- An elegant you will need a strong fixed aerial display where the point (minimum ½ ton safe performer twists weight bearing load per rigging themselves in, on, under point) for aerial artists to rig from and around a steel hoop if they are performing indoors: or ring suspended from the height varies according to the ceiling, usually about apparatus. -

JUGGLING in the U.S.S.R. in November 1975, I Took a One Week Tour to Leningrad and Ring Cascade Using a "Holster” at Each Side

Volume 28. No. 3 March 1976 INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS ASSOCIATION from Roger Dol/arhide JUGGLING IN THE U.S.S.R. In November 1975, I took a one week tour to Leningrad and ring cascade using a "holster” at each side. He twice pretended Moscow, Russia. I wasfortunate to see a number of jugglers while to accidentally miss the catch of all 9 down over his head before I was there. doing it perfectly to rousing applause and an encore bow. At the Leningrad Circus a man approximately 45 years old did Also on the show was a lady juggler who did a short routine an act which wasn’t terribly exciting, though his juggling was spinning 15-inch square glass sheets. She finished by spinning pretty good. He did a routine with 5, 4, 3 sticks including one on a stick balanced on her forehead and one on each hand showering the 5. He also balanced a pole with a tray of glassware simultaneously. Then, she did the routine of balancing a tray of on his head and juggled 4 metaf plates. For a finish, he cqnter- glassware on a sword balanced point to point on a dagger in her spun a heavy-looking round wooden table upside-down on a 10- mouth and climbing a swaying ladder ala Rosana and others. foot sectioned pole balanced on his forehead, then knocked the Finally, there were two excellent juggling acts as part of a really pole away and caught the table still spinning on a short pole held great music and variety floor show at the Arabat Restaurant in in his hands. -

HISTORY and STAGE METHOD of JUGGLING with HULA HOOPS Oleksandra Sobolieva Kyiv Municipal Academy of Circus and Variety Arts, Kiev, Ukraine

INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS IN MODERN SCIENCE № 2(11), 2017 UDC 792 (792.7) HISTORY AND STAGE METHOD OF JUGGLING WITH HULA HOOPS Oleksandra Sobolieva Kyiv Municipal Academy of Circus and Variety Arts, Kiev, Ukraine Research the methods of teaching juggling tricks by the big and small hula hoops, due to rising demand for hula hoops in recent years. Hula hoops acquire much popularity both abroad and in Ukraine, and are used not only in school, gymnastics and emotional pleasure, but also in a circus and juggling sports. Also highlights the main directions in the juggling with their features and how the juggling acts itself directly on human health. Also will be examined where this fascinating art form came to us, how it developed, and what kinds acquired in the present. Keywords: hula hoops, juggling, "track", stage technique, white substance, "helicopter". Problem definition and analysis of researches. Today juggling reached incredible development. There is no country where people would not be interested in juggling. There are a lot of conventions and juggling competitions, where people come from all over the world and share experiences with each other. But it should be noted, that there aren’t so much professional juggling schools. And if we talk about juggling by hula hoops, we can admit that there aren’t so much real experts in this field. Peter Bon, Tony Buzan in collaboration with Michael J. Gelb, Luke Burridge, Alexander Kiss, Paul Koshel and many others have written about all kinds of juggling, but left unattended hula hoops juggling. That is why in this article will be examples of author’s tricks with large and small hula hoops with a detailed description. -

Heft-Misterm-201909 95X150 002 PSD Und Druckdaei --- EN.Indd

Same as step 2 but 2 balls in right, 1 in the left hand. throw from one hand Begin with the right hand. Throw 30 throws from left to to the other and to other hand and when the ball is right, then right to left. count loud „1 and 2“ at its highest point, throw number Remember, throw 2, then 3. „1 and 2 and 3.“ Don‘t Then left » right » left. when the ball is at catch the balls. Do this about 30 its highest point. times. Then try to catch only the first thrown ball. Do this 30 times. Then try to catch the first two balls - 30 times. Then try to catch all 3 balls. www.MisterM.net/vid 2 balls, one in the left hand, Use a box and lean onto a one in the right. Throw wall. Roll balls on there and straight up, when the ball is practice step 2 and 3, at the highest point, throw the balls will roll slower. 3 BALL SET 5 BALL SET the other one straight up. Juggling scarves is much Of course, these scarves are not easier than juggling balls Take 2 scarves in only for juggling. Children love because they fly slower, hence one hand. Practice to play dress up with them, hide you have more time to react. lifting and releasing behind them or even make head Start with one scarf. Lift up and just one scarf. Best bands. Let your imagination run over and let it fall to the other to hold one with wild! hand. -

Understanding Siteswap Juggling Patterns a Guide for the Perplexed by Greg Phillips, [email protected]

Understanding Siteswap Juggling Patterns A guide for the perplexed by Greg Phillips, [email protected] Core rules (for all patterns) Synchronous siteswap (simultaneous throws) C1 We imagine a metronome ticking at some constant rate. Some juggling patterns involve both hands throwing at the Each tick is called a “beat.” same time. We describe these using synchronous siteswap. C2 We indicate each thrown object by a number that tells us how many beats later that object must be back in a hand S1 The right and left hands throw at the same time (which and ready to re-throw. counts as two throws) on every second beat. We group C3 We indicate a sequence of throws by a string of numbers the simultaneous throws in parentheses and separate the (plus punctuation and the letter x). We imagine these hands with commas. strings repeat indefinitely, making 531 equivalent to S2 We indicate throws that cross from hand to hand with an …531531531… So are 315 and 153 — can you see x (for ‘xing’). why? C4 The sum of all throw numbers in a siteswap string divided Rules C2 and S1 taken together demand that there be only by the number of throws in the string gives the number of even numbers in valid synchronous siteswaps. Can you see objects in the pattern. This must always be a whole why? The x notation of rule S2 is required to distinguish number. 531 is a three-ball pattern, since (5+3+1)/3 patterns like (4,4) (synchronous fountain) from (4x,4x) equals three; however, 532 cannot be juggled since (synchronous crossing). -

Solve CHALLENGE

solve CHALLENGE SOAR hit ©Disney Over the last 9 decades the US has seen many “ups and downs” with the nostalgic toy; however, the classic Duncan® Imperial® and Butterfly® yo-yos have become household names as they been rec- ognized as one of the most value in play for its price. Where else can one get hours on hours of play time for a toy under $10. Today, Duncan’s promotional arm extends beyond the traditional demonstrations and schools with social media, apps with tutorials, and partnerships with Disney Springs® and Boy Scouts of America®. From boomerangs, balls, and brain games to USB charged fighter planes & basketball sets, Duncan® now offers an entire range of skill and activity based toys that creates fun for kids of all ages! BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA® Yo-Yo Preview Adventure Yo-Yo Youth Program Launched in 2019, Duncan® and the Boy Scouts of America® yo-yo.com/Scouts introduced the Yo-Yo Preview Adventure as an opportunity for Cub Scouts to earn towards their advancement. This new adventure develops eye-hand coordination and teaches fundamental concepts of gravity, motion, and energy supporting STEM learning. Adventure • Opportunities to connect with more than 1.2 million Cub Scouts Belt Loop • 300,000 New Cub Scouts introduced into the program annually on average • Officially licensed by the Boy Scouts Of America to create BSA branded yo-yos • Opportunities to support intermediate Adventure For Following Ranks! Adventure Pin and advanced yo-yos • Increased social media and peer sharing for wider reach It isn’t just a yo-yo show, it’s a hands-on skill building activity that instills positive and emotional concepts with physical education benefits! yo-yo.com/schools 2 FROM DUNCAN¡DUNCAN! Brain Game Combo Set MagNetic Block MonuMental™ 3917BG-6 Puzzle Game Puzzle Game 3918MB 3915MM See Page 17 Pop 'N Hit™ 3682PS See Page 19 See Page 19 Junior Color Shift™ Puzzle Game 3916MB-A Yo-Yo/Brain Game Display 3283DY See Page 7 See Page 17 Pop 'N Hit™ PDQ 3682PS-PDQ See Page 38 See Page 39 The Original. -

The Passing Zone, a Juggling Duo That Performs in a Benefit for Dream Come True Sunday at Lehigh University’S Zoellner Arts Center

The P a ssing Zone Laughter a Chain Reaction for Juggling Duo mcall.com By Dave Howell – 11.2005 Jon Wee and Owen Morse understand that people have to juggle many important things in life — work, family, chainsaws. Well, maybe not chainsaws. But Wee and Morse do balance all three as The Passing Zone, a juggling duo that performs in a benefit for Dream Come True Sunday at Lehigh University’s Zoellner Arts Center. In separate phone conversations from their homes in California, Wee and Morse say that they may be jugglers, but their humor is a bit more adult. The fact that they are pictured holding chain saws in publicity photos might give that away. Actually the ‘’chain saw ballet,’’ which has the duo dressed in tights, is part of a spectacular show that will include flaming torches and ‘’people juggling,’’ in which three volunteers from the audience will substitute for the usual clubs and cigar boxes. Morse brags about the duo’s new ‘’Boomerang Rubber Band’’ routine, which uses a single rubber band. There will be plenty of humor, too. ‘’It’s a comedy more than a juggling show,’’ says Wee. ‘’People often come up to us and say, ‘I had no idea it would be this funny.’’’ Morse says that the duo banter back and forth, and spoof TV commercials using objects like Chia Pets and the Thighmaster. The duo has opened for many comedians, including Bob Newhart, Bill Cosby, and Rita Rudner, and has appeared at the Montreal Comedy Festival. For many years The Passing Zone only appeared at private events, says Wee, ‘’mostly different companies, big meetings and awards ceremonies.’’ Typically companies hire the juggling duo to illustrate business principles, like the value of teamwork. -

Diabolo Orientation Stabilization by Learning Predictive Model for Unstable Unknown-Dynamics Juggling Manipulation

2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) October 25-29, 2020, Las Vegas, NV, USA (Virtual) Diabolo Orientation Stabilization by Learning Predictive Model for Unstable Unknown-Dynamics Juggling Manipulation Takayuki Murooka, Kei Okada and Masayuki Inaba Abstract— Juggling manipulation is one of difficult manipu- lation to acquire since some of such manipulation is unstable and also its physical model is unknown due to the complex non- prehensile manipulation. To acquire these unstable unknown- dynamics juggling manipulation, we propose a method for designing the predictive model of manipulation with a deep neural network, and a real-time optimal control law with some robustness and adaptability using backpropagation of the network. In this study, we apply this method to diabolo orientation stabilization, which is one of unstable unknown- dynamics juggling manipulation. We verify the effectiveness (a) Diabolo tools. A red diabolo top of the proposed method by comparing with basic controllers and two white sticks connected with a rope. such as P Controller or PID Controller, and also check the (b) Diabolo orientation adaptability of the proposed controller by some experiments stabilization by PR2. with a real life-sized humanoid robot. Fig. 1. Diabolo orientation stabilization. I. INTRODUCTION A. Related Works 1) Robot as Entertainment: Entertainment robots have Robots are expected to behave and manipulate like human, been widely researched and developed to enrich human life and in order to realize that, researchers have been tackling [1], [2], [3], and also entertainment robots have significant a wide range of motion planning or control with various effects as therapy for elderly people or children with autism robots. -

Braids and Juggling Patterns Matthew Am Cauley Harvey Mudd College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont HMC Senior Theses HMC Student Scholarship 2003 Braids and Juggling Patterns Matthew aM cauley Harvey Mudd College Recommended Citation Macauley, Matthew, "Braids and Juggling Patterns" (2003). HMC Senior Theses. 151. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/hmc_theses/151 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the HMC Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in HMC Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Braids and Juggling Patterns by Matthew Macauley Michael Orrison, Advisor Advisor: Second Reader: (Jim Hoste) May 2003 Department of Mathematics Abstract Braids and Juggling Patterns by Matthew Macauley May 2003 There are several ways to describe juggling patterns mathematically using com- binatorics and algebra. In my thesis I use these ideas to build a new system using braid groups. A new kind of graph arises that helps describe all braids that can be juggled. Table of Contents List of Figures iii Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Siteswap Notation 4 Chapter 3: Symmetric Groups 8 3.1 Siteswap Permutations . 8 3.2 Interesting Questions . 9 Chapter 4: Stack Notation 10 Chapter 5: Profile Braids 13 5.1 Polya Theory . 14 5.2 Interesting Questions . 17 Chapter 6: Braids and Juggling 19 6.1 The Braid Group . 19 6.2 Braids of Juggling Patterns . 22 6.3 Counting Jugglable Braids . 24 6.4 Determining Unbraids . 27 6.4.1 Setting the crossing numbers to zero. 32 6.4.2 The complete system of equations . -

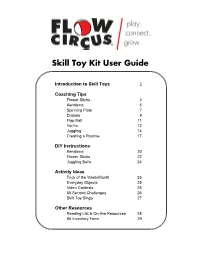

Skill Toy Kit User Guide

Skill Toy Kit User Guide Introduction to Skill Toys 2 Coaching Tips Flower Sticks 3 Kendama 5 Spinning Plate 7 Diabolo 9 Flop Ball 11 Yo-Yo 12 Juggling 14 Creating a Routine 17 DIY Instructions Kendama 20 Flower Sticks 22 Juggling Balls 24 Activity Ideas Trick of the Week/Month 25 Everyday Objects 25 Video Contests 25 60 Second Challenges 26 Skill Toy Bingo 27 Other Resources Reading List & On-line Resources 28 Kit Inventory Form 29 Introduction to Skill Toys You and your team are about to embark on a fun adventure into the world of skill toys. Each toy included in this kit has its own story, design, and body of tricks. Most of them have a lower barrier to entry than juggling, and the following lessons of good posture, mindfulness, problem solving, and goal setting apply to all. Before getting started with any of the skill toys, it is important to remember to relax. Stand with legs shoulder width apart, bend your knees, and take deep breaths. Many of them require you to absorb energy. We have found that the more stressed a player is, the more likely he/she will be to struggle. Not surprisingly, adults tend to have this problem more than kids. If you have players getting frustrated, remind them to relax. Playing should be fun! Also, remind yourself and other players that even the drops or mess-ups can give us valuable information. If they observe what is happening when they attempt to use the skill toys, they can use this information to problem solve. -

The Mathematics of Juggling by Burkard Polster

The Mathematics of Juggling by Burkard Polster Next time you see some jugglers practising in a park, ask them whether they like mathematics. Chances are, they do. In fact, a lot of mathematically wired people would agree that juggling is “cool” and most younger mathe- maticians, physicists, computer scientists, engineers, etc. will at least have given juggling three balls a go at some point in their lives. I myself also belong to this category and, although I am only speaking for myself, I am sure that many serious mathematical jugglers would agree that the satisfaction they get out of mastering a fancy juggling pattern is very similar to that of seeing a beautiful equation, or proof of a theorem click into place. Given this fascination with juggling, it is probably not surprising that mathematical jugglers have investigated what mathematics can be found in juggling. But before we embark on a tour of the mathematics of juggling, here is a little bit of a history. 1 A mini history The earliest historical evidence of juggling is a 4000 year old wall painting in an ancient Egyptian tomb. Here is a tracing of part of this painting showing four jugglers juggling up to three objects each. The earliest juggling mathematician we know of is Abu Sahl al-Kuhi who lived around the 10th century. Before becoming famous as a mathematician, he juggled glass bottles in the market place of Baghdad. But he seems to be the exception. Until quite recently, it was mostly professional circus performers or their precursors, who engaged in juggling.