BANANA PLANTATION.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Checklist of Hoya (Asclepiadaceae) in the Flora of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam

Turczaninowia 20 (3): 103–147 (2017) ISSN 1560–7259 (print edition) DOI: 10.14258/turczaninowia.20.3.10 TURCZANINOWIA http://turczaninowia.asu.ru ISSN 1560–7267 (online edition) УДК 582.394:581.4 Preliminary checklist of Hoya (Asclepiadaceae) in the flora of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam L. V. Averyanov1, Van The Pham2, T. V. Maisak1, Tuan Anh Le3, Van Canh Nguyen4, Hoang Tuan Nguyen5, Phi Tam Nguyen6, Khang Sinh Nguyen2, Vu Khoi Nguyen7, Tien Hiep Nguyen8, M. Rodda9 1 Komarov Botanical Institute, Prof. Popov, 2; St. Petersburg, RF-197376, Russia E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Sciences and Technology, 18 Hoang Quoc Viet, Cau Giay, Ha Noi, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 3Quang Tri Center of Science and Technology, Mientrung Institute for Scientific Research, 121 Ly Thuong Kiet, Dong Ha, Quang Tri, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 4 3/12/3 Vo Van Kiet Street, Buon Ma Thuot City, Dak Lak province, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 5Department of Pharmacognosy, Hanoi University of Pharmacy, 15 Le Thanh Tong, Hoan Kiem, Hanoi, Vietnam E-mail: [email protected] 6Viet Nam Post and Telecommunications Group – VNPT, Lam Dong 8 Tran Phu Street, Da Lat City, Lam Dong Province, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 7Wildlife At Risk, 202/10 Nguyen Xi st., ward 26, Binh Thanh, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam. E-mail: [email protected] 8Center for Plant Conservation, no. 25/32, lane 191, Lac Long Quan, Nghia Do, Cau Giay District, Ha Noi, Vietnam E-mail: [email protected] 9Herbarium, Singapore Botanic Gardens, 1 Cluny Road, Singapore 259569. -

Performance of Savings Groups in Mountainous Laos Under Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Policy

<Articles>Performance of Savings Groups in Mountainous Title Laos under Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Policy Author(s) FUJITA, Koichi; Ohno, Akihiko; Chansathith, Chaleunsinh Citation Southeast Asian Studies (2015), 3(4): 39-71 Issue Date 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/199240 Right ©Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Performance of Savings Groups in Mountainous Laos under Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Policy Fujita Koichi,* Ohno Akihiko,** and Chansathith Chaleunsinh*** The shifting cultivation stabilization policy after the mid-1990s in northern Laos had a fundamental impact on rural lives, including an accelerated migration of non-Lao ethnic people. Based on household-level detailed data collected in 2010–11 from eight villages in Luang Prabang Province, we analyze first the differential impacts of such a policy on different types of villages in terms of location (access to urban centers), land endowments, ethnic composition, etc. Then we examine the role and limitations of village-level savings groups (SGs) introduced by an NGO (supported by the Lao Women’s Union) from the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century. It is found that most of the SGs faced difficulties in accumulating savings, which resulted in a shortage of funds that could be credited to needy members. Money borrowed from SGs is used mainly for medical treatment and consumption. It is suggested that income stabilization and diversification is one -

A Cross Sectional Study 80 Pertussis in Lao PDR: Seroprevalence and Disease

Summary 01 Letter from Dr. Paul BREY 06 Arbovirus and Emerging viral diseases laboratory Lao-French joint Lab 1 08 Arbovirus surveillance in Lao PDR 10 Ecomore2 project 11 Inputs of Research and development activities in Ecomore2 project 14 COVID19 activities 15 Training activities 16 Education activities (Elodie Calvez) 16 Evaluation of new diagnostic tools for Chikungunya virus 17 Medical Entomology & Biology of Disease Vectors Laboratory Lao-French joint Lab 2 20 Tick Map 3 project: Mapping of Vectors and Reservoir Hosts in Lao PDR 27 Origins, natural reservoirs and Interspecies transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and other SARS-like CoVs 31 ECOnomic Development, ECOsystem Modifications, and Emerging Infectious Diseases Risk Evaluation (ECOMORE II). Entomology work package. 39 Assessing the risk of insecticide resistance in the tiger mosquito: A predictive approach combining experimental selection and molecular markers (TigeRisk) 41 Entomological field surveys in selected high-risk dengue transmission areas in Vientiane. (Baseline survey) 45 Vaccine Preventable Diseases Laboratory Lao-Lux Lab 52 Hepatitis B virus in Lao Blood donors: a nationwide serostudyviruses 69 Hepatitis B virus in Lao dentists: a cross-sectional serological study 63 Positive impact of HBV vaccination in Lao PDR 71 Timeliness of immunisation with Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis whole cell– Hepatitis B–Haemophilus influenzae Type B at different levels of the health care system in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic: a cross sectional study 80 Pertussis in Lao PDR: Seroprevalence -

Performance of Savings Groups in Mountainous Laos Under Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Policy Author(S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository <Articles>Performance of Savings Groups in Mountainous Title Laos under Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Policy Author(s) FUJITA, Koichi; Ohno, Akihiko; Chansathith, Chaleunsinh Citation Southeast Asian Studies (2015), 3(4): 39-71 Issue Date 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/199240 Right ©Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Performance of Savings Groups in Mountainous Laos under Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Policy Fujita Koichi,* Ohno Akihiko,** and Chansathith Chaleunsinh*** The shifting cultivation stabilization policy after the mid-1990s in northern Laos had a fundamental impact on rural lives, including an accelerated migration of non-Lao ethnic people. Based on household-level detailed data collected in 2010–11 from eight villages in Luang Prabang Province, we analyze first the differential impacts of such a policy on different types of villages in terms of location (access to urban centers), land endowments, ethnic composition, etc. Then we examine the role and limitations of village-level savings groups (SGs) introduced by an NGO (supported by the Lao Women’s Union) from the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century. It is found that most of the SGs faced difficulties in accumulating savings, which resulted in a shortage of funds that could be credited to needy members. Money borrowed from SGs is used mainly for medical treatment and consumption. It is suggested that income stabilization and diversification is one of the key factors that facilitate villagers’ participation in SGs. -

Performance of Savings Groups in Mountainous Laos Under Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Policy

Performance of Savings Groups in Mountainous Laos under Shifting Cultivation Stabilization Policy Fujita Koichi,* Ohno Akihiko,** and Chansathith Chaleunsinh*** The shifting cultivation stabilization policy after the mid-1990s in northern Laos had a fundamental impact on rural lives, including an accelerated migration of non-Lao ethnic people. Based on household-level detailed data collected in 2010–11 from eight villages in Luang Prabang Province, we analyze first the differential impacts of such a policy on different types of villages in terms of location (access to urban centers), land endowments, ethnic composition, etc. Then we examine the role and limitations of village-level savings groups (SGs) introduced by an NGO (supported by the Lao Women’s Union) from the middle of the first decade of the twenty-first century. It is found that most of the SGs faced difficulties in accumulating savings, which resulted in a shortage of funds that could be credited to needy members. Money borrowed from SGs is used mainly for medical treatment and consumption. It is suggested that income stabilization and diversification is one of the key factors that facilitate villagers’ participation in SGs. Keywords: Laos, savings group, shifting cultivation stabilization policy, emergency I Introduction In the late 1990s, village savings and credit groups (hereafter savings groups, or SGs) were introduced from Northeast Thailand to Laos by NGOs—Foundation for Integrated Agricultural and Environmental Management and Community Organizations Develop- ment Institute of Thailand—with the cooperation of the Lao Women’s Union (LWU), first to villages in Vientiane Municipality and later to hinterland areas where the market economy was less developed (see Ohno and Fujita, special issue introduction paper). -

POST-DISASTER NEEDS ASSESSMENT 2018 FLOODS, LAO PDR Front Cover: Disaster-Affected Family in Sanamxay, Attapeu, August-September 2018

POST-DISASTER NEEDS ASSESSMENT 2018 FLOODS, LAO PDR Front cover: Disaster-affected family in Sanamxay, Attapeu, August-September 2018. Photo credit: UNFPA Disclaimer: This report summarizes the findings of the Post-Disaster Needs Assessment that took place between September 24 and October 19, 2018. The report is based on national data as of October 2018 gathered during the assessment. Published and dated: Government of Lao People’s Democratic Republic, December 2018. PREPARED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC FACILITATED BY WITH FINANCIAL AND TECHNICAL SUPPORT FROM Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms v ບບບບບForeword vii Acknowledgments ix INTRODUCTION 6 Disaster Risk Profile of Lao PDR 7 Socioeconomic Context of Lao PDR 8 Description of 2018 Disaster 8 Government and Humanitarian Response 9 Assessment Methodology 10 ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPACTS 11 Macroeconomic Impact 12 Human Development Impacts 22 DAMAGE, LOSSES, AND NEEDS 34 SOCIAL SECTORS 34 Housing and Settlements 35 Education 43 Health and Nutrition 51 Culture 56 PRODUCTIVE SECTORS 64 Agriculture 65 Tourism 76 Industry and Commerce 83 INFRASTRUCTURE SECTORS 88 Transport 89 Waterways 97 Water Supply and Sanitation 103 Electricity 109 CROSS-CUTTING ISSUES 114 Disaster Risk Management, Environment, and Climate Change Adaptation 115 Governance 124 Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) 128 DISASTER RECOVERY FRAMEWORK 132 Way Forward: A Disaster Recovery Framework 133 ANNEX 142 Annex 1 — Map of Lao PDR 142 i Table List Table 1 — Summary of the Damage and Losses (billion -

The Lao People's Democratic Republic the MASTER PLAN

No. The Lao People’s Democratic Republic THE MASTER PLAN STUDY ON SMALL-HYDRO IN NORTHERN LAOS Final Report: Volume 1 MAIN REPORT December 2005 Japan International Cooperation Agency Economic Development Department ED JR 05-108 Ministry of Industry and Handicrafts of Lao PDR THE MASTER PLAN STUDY ON SMALL-HYDRO IN NORTHERN LAOS FINAL REPORT : VOLUME 1 MAIN REPORT December 2005 KRI International Corporation Preface In response to a request from Lao People's Democratic Republic, the Government of Japan decided to conduct The Master Plan Study on Small Hydropower in Northern Laos and entrusted the study to Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA sent a study team led by Mr. Ichiro Araki, Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. and KRI International Corp., to Laos six times from February 2004 to November 2005. The study team held discussions with the officials concerned of the government of Laos and conducted a series of field surveys. After returning to Japan, the study team carried out further studies and compiled the final results in this report. I hope this report will be utilized for contributing to develop the small hydropower in Northern Laos and to the promotion of amity between our two countries. I also express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the government of Laos for their close cooperation throughout the study. December 2005 Tadashi IZAWA Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency Consulting Engineers December 2005 Mr. Tadashi IZAWA Vice President Japan International Cooperation Agency Tokyo, Japan Dear Sir, LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL We are pleased to submit herewith the Final Report of Master Plan Study on Small-Hydro in Northern Laos. -

Nam Ou River Cascade Hydropower Project Nam Ou River

(https://www.nsenergybusiness.com/) Home (Https://Www.Nsenergybusiness.Com) » Projects (Https://Www.Nsenergybusiness.Com/Projects) » Nam Ou River Cascade Hydropower Project Nam Ou River Cascade Hydropower Project POWER (HTTPS://WWW.NSENERGYBUSINESS.COM/./POWER/) HYDRO (HTTPS://WWW.NSENERGYBUSINESS.COM/POWER/HYDRO) DAM (HTTPS://WWW.NSENERGYBUSINESS.COM/HYDRO/DAM) Plant Type : Location : Capacity : Construction Started : Cascade hydropower project Phongsaly province-Luang Prabang 1,272MW October 2012 i L MORE Nam Ou river cascade hydropower project (HPP) is being developed on the banks of the Nam Ou river, which is the largest tributary of Mekong River (ht intp Laos.s://twitter.com/intent/tweet? (htt Ou+River+TheCa hydropowerscade+H projectydro (https://wwwpower+P.nsenerrojegybusiness.com/projects/rogun-hydropowerct&url=https%3A%2F%2Fw-project/)ww.n hassenergybusiness.com%2Fprojects%2Fnam-url=https://w seven isolated cascadeou units-riv beinger- cconstructedascade in-h difyferentdrop districtsower along-pro theje cNamt% Ou2F River&vi.a The=NS+Energy) ou-ri cascade units are being developed in two phases with a cumulative capacity of 1,272MW. The project is owned by Laos State Electricity Corporation, Electricite du Laos (EDL). It is being developed by a joint venture of EDL (20%) and Sinohydro (80%), a subsidiary of Power China, under a 25-year build, operate and transfer (BOT) agreement signed in April 2011. The estimated investment in the project is £2.1bn ($2.73bn). Phase one of the project consisting of three units with a total installed capacity of 540MW was commissioned in January 2017. PROJECT GALLERY The construction work on phase two, which comprises of four units with a total installed capacity of 732MW, began in April 2016. -

(Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) from Northern Laos

Zootaxa 3586: 264–271 (2012) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:1A7BCEC8-39FA-43E4-9303-08FFA241270E A new species of Metzia (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) from Northern Laos KOICHI SHIBUKAWA1, PHOUVIN PHOUSAVANH2,3, KONEUMA PHONGSA4 & AKIHISA IWATA3 1Nagao Natural Environment Foundation, 3-10-10 Shitaya, Taito-ku, Tokyo 110-0004, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 2Faculty of Agriculture, National University of Laos, P.O. Box 7322, Nabong, Vientiane, Lao PDR. 3Laboratory of Ecology and Environment, Division of Southeast Asian Area Studies, Graduate School of Asian and African Area Stud- ies, Kyoto University Yoshida, Shimoadachi-cho 46, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan. E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, National University of Laos, P.O. Box 7322, Dongdok, Vientiane, Lao PDR. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new cyprinid fish, Metzia bounthobi, is described on the basis of 18 specimens (including 10 specimens in type series) from the Mekong River basin in Phongsaly and Luang Prabang Provinces, northern Laos. The species is distinguished from congeners by having the following diagnostic traits: 18–20 branched anal-fin rays (vs. 10–18 in the others); 49–55 lateral-line scale rows (vs. 35–48); 33–36 predorsal scale rows (vs. 15–20); 20–22 circumpeduncular scale rows (vs. 14–18); 8–10 gill rakers on outer surface of first gill arch (vs. 12–18). The new species also resembles species of Hemic- ulterella, Ischikauia and at least some species of Anabarilius, in sharing a sharp keel developed only between the base of the pelvic fin and anus, soft last unbranched dorsal-fin ray, and air bladder composed of two chambers; however, M. -

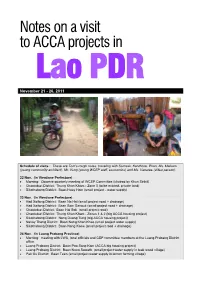

Notes on a Visit to ACCA Projects In

Notes on a visit to ACCA projects in November 21 - 26, 2011 Schedule of visits : These are Tom's rough notes, traveling with Somsak, Kanthone, Phan, Ms. Maikam (young community architect), Mr. Vong (young WCEP staff, economics) and Ms. Vanaree (video person). 22 Nov. (in Vientiane Prefecture) Morning: Observe quarterly meeting of WCEP Committee (chaired by Khun Sirikit) Chantaburi District: Thung Khan Kham - Zone 3 (to be evicted, private land) Sikothabong District: Baan Huay Hom (small project - water supply) 23 Nov. (in Vientiane Prefecture) Had Xaifong District: Baan Na Hai (small project road + drainage) Had Xaifong District: Baan Som Sanouk (small project road + drainage) Chantaburi District: Baan Hai Sok (small project road) Chantaburi District: Thung Khan Kham - Zones 1 & 2 (big ACCA housing project) Sikothabong District: Nong Duang Tung (big ACCA housing project) Naxay Thong District: Baan Nong Khan Kheo (small project water supply) Sikothabong District: Baan Nong Kaew (small project road + drainage) 24 Nov. (in Luang Prabang Province) Morning: meeting with LWU, local officials and CDF committee members at the Luang Prabang District office Luang Prabang District: Baan Poo Sang Kam (ACCA big housing project) Luang Prabang District: Baan Noon Sawath (small project water supply in teak wood village) Pak Ou District: Baan Teen (small project water supply in lemon farming village) 25 Nov. (in Luang Prabang Province) Nambak District: Baan Huay Yen (small project toilets) Nambak District: Nayang Tai (small project toilets) -

Trade Development Facility Scoping Study on Trade,Food Production,And Service Sector Linkages in Luang Prabang

Final Report 19 August 2011 TRADE DEVELOPMENT FACILITY SCOPING STUDY ON TRADE, FOOD PRODUCTION, AND SERVICE SECTOR LINKAGES IN LUANG PRABANG DRAFT FINAL REPORT 19 AUGUST 2011 PREPARED FOR THE WORLD BANK AND TRADE PROMOTION AND PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT MINISTRY OF INDUSTRY AND COMMERCE VIENTIANE, LAO PDR 1 Final Report 19 August 2011 Preface The Scoping Study on Trade, Food Production, and Service Sector Linkages in Luang Prabang was financed by the Trade Development Facility, a multi-donor trust fund to support trade and investment, and the Lao Ministry of Industry and Commerce, and administered by the World Bank. The Study was undertaken by Anthony M. Zola, a consultant to the World Bank in February and March 2011. The Scoping Study presents a description of the current situation related to food production, food trade, and food safety in Luang Prabang Province and the importing of food products from neighboring countries. The reader is advised that the momentum of development of tourism and investments in the hospitality industry in Luang Prabang Province is highly dynamic and is changing almost daily. Thus, the report captures the situation as it existed during the first half of 2011. The mission received significant support from the World Bank Mission in Vientiane, Lao PDR, the Trade Promotion and Product Development Department, Ministry of Industry and Commerce, and provincial and district officials in Luang Prabang Province. Numerous chefs, hotel and restaurant managers, food traders and representatives of the business community in Luang Prabang also were very generous with their time. Administrative arrangements, travel logistics, and appointments with the numerous people contacted in the course of the assignment were all handled with expertise by the staff at the World Bank Mission, Trade Promotion and Product Development Department, and the Provincial Industry and Commerce Office. -

Crispy River Weed ໄຄ , ໄຄແຜ່ ນ

ບດສົົົົ ງລວມກັັັັ ່່່່ ຽວກບຜະລັັັັ ດຕະພິິິິ ນຊັັັັ ວະນາໆີີີີ ພນກະສັັັັ ກິິິິ າໍໍໍໍ ຂອງ ສປປ ລາວ Profile of Lao Agro-Biodiversity Products Nr.4: Crispy River Weed ໄຄ , ໄຄແຜ່ ນ Draft, 19 August 2016 Vientiane, 19 August 2016 Lao WomensUnion, Luang Prabang Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Botanical Characteristics of River Weed ......................................................................................... 1 3. River weed in the eco-system ......................................................................................................... 3 3.1. Changes in Eco-system and Impacts on River Weed ........................................................................ 3 4. Distribution of River Weed and Crispy River Weed Production in Lao PDR, particularly in Luang Prabang Province ..................................................................................................................................... 4 4.1. Distribution of River Weed inLuang Phabang .................................................................................. 4 4.2. Crispy River Weed production Resources ........................................................................................ 6 4.2.1. Luang Prabang Province .......................................................................................................... 6 4.2.2. Houaphan Province ..............................................................................................................