Inertially Induced Connections Between Subgyres in the South Indian Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fronts in the World Ocean's Large Marine Ecosystems. ICES CM 2007

- 1 - This paper can be freely cited without prior reference to the authors International Council ICES CM 2007/D:21 for the Exploration Theme Session D: Comparative Marine Ecosystem of the Sea (ICES) Structure and Function: Descriptors and Characteristics Fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems Igor M. Belkin and Peter C. Cornillon Abstract. Oceanic fronts shape marine ecosystems; therefore front mapping and characterization is one of the most important aspects of physical oceanography. Here we report on the first effort to map and describe all major fronts in the World Ocean’s Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). Apart from a geographical review, these fronts are classified according to their origin and physical mechanisms that maintain them. This first-ever zero-order pattern of the LME fronts is based on a unique global frontal data base assembled at the University of Rhode Island. Thermal fronts were automatically derived from 12 years (1985-1996) of twice-daily satellite 9-km resolution global AVHRR SST fields with the Cayula-Cornillon front detection algorithm. These frontal maps serve as guidance in using hydrographic data to explore subsurface thermohaline fronts, whose surface thermal signatures have been mapped from space. Our most recent study of chlorophyll fronts in the Northwest Atlantic from high-resolution 1-km data (Belkin and O’Reilly, 2007) revealed a close spatial association between chlorophyll fronts and SST fronts, suggesting causative links between these two types of fronts. Keywords: Fronts; Large Marine Ecosystems; World Ocean; sea surface temperature. Igor M. Belkin: Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island, 215 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA [tel.: +1 401 874 6533, fax: +1 874 6728, email: [email protected]]. -

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability

Diversity Visa Program, DV 2019-2021: Number of Entries During Each Online Registration Period by Region and Country of Chargeability The totals below DO NOT represent the number of diversity visas issued nor the number of selected entrants Countries marked with a "0" indicate that there were no entrants from that country or area. Countries marked with "N/A" were typically not eligible for that program year. FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2021 Region Foreign State of Chargeabiliy Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Entrants Derivatives Total Africa Algeria 227,019 123,716 350,735 252,684 140,422 393,106 221,212 129,004 350,216 Africa Angola 17,707 25,543 43,250 14,866 20,037 34,903 14,676 18,086 32,762 Africa Benin 128,911 27,579 156,490 150,386 26,627 177,013 92,847 13,149 105,996 Africa Botswana 518 462 980 552 406 958 237 177 414 Africa Burkina Faso 37,065 7,374 44,439 30,102 5,877 35,979 6,318 2,591 8,909 Africa Burundi 20,680 16,295 36,975 22,049 19,168 41,217 12,287 11,023 23,310 Africa Cabo Verde 1,377 1,272 2,649 894 778 1,672 420 312 732 Africa Cameroon 310,373 147,979 458,352 310,802 165,676 476,478 150,970 93,151 244,121 Africa Central African Republic 1,359 893 2,252 1,242 636 1,878 906 424 1,330 Africa Chad 5,003 1,978 6,981 8,940 3,159 12,099 7,177 2,220 9,397 Africa Comoros 296 224 520 293 128 421 264 111 375 Africa Congo-Brazzaville 21,793 15,175 36,968 25,592 19,430 45,022 21,958 16,659 38,617 Africa Congo-Kinshasa 617,573 385,505 1,003,078 924,918 415,166 1,340,084 593,917 153,856 747,773 Africa Cote d'Ivoire 160,790 -

Basin-Wide Seasonal Evolution of the Indian Ocean's Phytoplankton Blooms

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 112, C12014, doi:10.1029/2007JC004090, 2007 Click Here for Full Article Basin-wide seasonal evolution of the Indian Ocean’s phytoplankton blooms M. Le´vy,1,2 D. Shankar,2 J.-M. Andre´,1,2 S. S. C. Shenoi,2 F. Durand,2,3 and C. de Boyer Monte´gut4 Received 5 January 2007; revised 2 August 2007; accepted 5 September 2007; published 21 December 2007. [1] A climatology of Sea-viewing Wide Field-of-View Sensor (SeaWiFS) chlorophyll data over the Indian Ocean is used to examine the bloom variability patterns, identifying spatio-temporal contrasts in bloom appearance and intensity and relating them to the variability of the physical environment. The near-surface ocean dynamics is assessed using an ocean general circulation model (OGCM). It is found that over a large part of the basin, the seasonal cycle of phytoplankton is characterized by two consecutive blooms, one during the summer monsoon, and the other during the winter monsoon. Each bloom is described by means of two parameters, the timing of the bloom onset and the cumulated increase in chlorophyll during the bloom. This yields a regional image of the influence of the two monsoons on phytoplankton, with distinct regions emerging in summer and in winter. By comparing the bloom patterns with dynamical features derived from the OGCM (horizontal and vertical velocities and mixed-layer depth), it is shown that the regional structure of the blooms is intimately linked with the horizontal and vertical circulations forced by the monsoons. Moreover, this comparison permits the assessment of some of the physical mechanisms that drive the bloom patterns, and points out the regions where these mechanisms need to be further investigated. -

Management of Demersal Fisheries Resources of the Southern Indian Ocean

FAO Fisheries Circular No. 1020 FIRM/C1020 (En) ISSN 0429-9329 MANAGEMENT OF DEMERSAL FISHERIES RESOURCES OF THE SOUTHERN INDIAN OCEAN Cover photographs courtesy of Mr Hannes du Preez, Pioneer Fishing, Heerengracht, South Africa. Juvenile of Oreosoma atlanticum (Oreosomatidae). This fish was caught at 39° 15’ S, 45° 00’ E, late in 2005 at around 650 m while mid-water trawling for alfonsinos. This genus is remarkable for the large conical tubercles that cover the dorsal surface of the younger fish. Illustration by Ms Emanuela D’Antoni, Marine Resources Service, FAO Fisheries Department. Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: Sales and Marketing Group Information Division FAO Viale delle Terme di Caracalla 00153 Rome, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (+39) 06 57053360 FAO Fisheries Circular No. 1020 FIRM/C1020 (En) MANAGEMENT OF DEMERSAL FISHERIES RESOURCES OF THE SOUTHERN INDIAN OCEAN Report of the fourth and fifth Ad Hoc Meetings on Potential Management Initiatives of Deepwater Fisheries Operators in the Southern Indian Ocean (Kameeldrift East, South Africa, 12–19 February 2006 and Albion, Petite Rivière, Mauritius, 26–28 April 2006) including specification of benthic protected areas and a 2006 programme of fisheries research. compiled by Ross Shotton FAO Fisheries Department FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2006 The mention or omission of specific companies, their products or brand names does not imply any endorsement or judgement by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Automatic Exchange of Information: Status of Commitments

As of 27 September 2021 AUTOMATIC EXCHANGE OF INFORMATION (AEOI): STATUS OF COMMITMENTS1 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES IN 2017 (49) Anguilla, Argentina, Belgium, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands, Bulgaria, Cayman Islands, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus2, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Finland, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Guernsey, Hungary, Iceland, India, Ireland, Isle of Man, Italy, Jersey, Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Montserrat, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Seychelles, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Turks and Caicos Islands, United Kingdom JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2018 (51) Andorra, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan3, The Bahamas, Bahrain, Barbados, Belize, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, China, Cook Islands, Costa Rica, Curacao, Dominica4, Greenland, Grenada, Hong Kong (China), Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Lebanon, Macau (China), Malaysia, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Monaco, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue4, Pakistan3, Panama, Qatar, Russia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Sint Maarten4, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago4, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Uruguay, Vanuatu JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2019 (2) Ghana3, Kuwait5 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2020 (3) Nigeria3, Oman5, Peru3 JURISDICTIONS UNDERTAKING FIRST EXCHANGES BY 2021 (3) Albania3, 7, Ecuador3, Kazakhstan6 -

Connectivity and Population Structure of Albacore Tuna Across Southeast Atlantic and Southwest Indian Oceans Inferred from Multi

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Connectivity and population structure of albacore tuna across southeast Atlantic and southwest Indian Oceans inferred from multidisciplinary methodology Natacha Nikolic1,2,3,12*, Iratxe Montes4, Maxime Lalire5, Alexis Puech1, Nathalie Bodin6,11,13, Sophie Arnaud‑Haond7, Sven Kerwath8,9, Emmanuel Corse2,14, Philippe Gaspar 5,10, Stéphanie Hollanda11, Jérôme Bourjea1, Wendy West8,15 & Sylvain Bonhommeau 1,15 Albacore tuna (Thunnus alalunga) is an important target of tuna fsheries in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The commercial catch of albacore is the highest globally among all temperate tuna species, contributing around 6% in weight to global tuna catches over the last decade. The accurate assessment and management of this heavily exploited resource requires a robust understanding of the species’ biology and of the pattern of connectivity among oceanic regions, yet Indian Ocean albacore population dynamics remain poorly understood and its level of connectivity with the Atlantic Ocean population is uncertain. We analysed morphometrics and genetics of albacore (n = 1,874) in the southwest Indian (SWIO) and southeast Atlantic (SEAO) Oceans to investigate the connectivity and population structure. Furthermore, we examined the species’ dispersal potential by modelling particle drift through major oceanographic features. Males appear larger than females, except in South African waters, yet the length–weight relationship only showed signifcant male–female diference in one region (east of Madagascar and Reunion waters). The present study produced a genetic diferentiation between the southeast Atlantic and southwest Indian Oceans, supporting their demographic independence. The particle drift models suggested dispersal potential of early life stages from SWIO to SEAO and adult or sub-adult migration from SEAO to SWIO. -

Summary Record

SC60 summary record CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Sixtieth meeting of the Standing Committee Doha (Qatar), 25 March 2010 SUMMARY RECORD 1. Election of the Chair, Vice-Chair and Alternate Vice-Chair of the Standing Committee The Secretariat, as temporary chair of the meeting, confirmed that, following the elections at CoP15, the current members of the Standing Committee were as follows: Africa: Botswana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt and Uganda; Asia: the Islamic Republic of Iran, Japan and Kuwait; Central and South America and the Caribbean: Colombia, Costa Rica and Dominica; Europe: Bulgaria, Norway, Ukraine and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland; North America: the United States of America; Oceania: Australia; and Non-elected members: Qatar (previous host country), Switzerland (Depositary Government) and Thailand (next host country). Norway was nominated as the new Chair of the Standing Committee. Norway thanked the Committee for the honour but noted that their acceptance of this position would have to be confirmed in the following weeks. Therefore the Committee agreed that Norway would be the new Chair, subject to its confirmation. The Committee elected the United States as its Vice-Chair and Kuwait as its Alternate Vice-Chair. The representative of Norway chaired the rest of the meeting, thanking the members of the Committee for the privilege and for the confidence they had shown in his country. During discussion of this item, interventions were made by the regional representatives of Asia (Kuwait), Europe (Norway) and North America (the United States), and by Chile. -

Member States

1/10/19 Total: 193 MEMBER STATES Afghanistan Democratic Republic of the Congo Albania Denmark Algeria Djibouti Andorra Dominica Angola Dominican Republic* Antigua and Barbuda Ecuador Argentina* Egypt* Armenia El Salvador Australia* Equatorial Guinea* Austria Eritrea Azerbaijan Estonia Bahamas Eswatini Bahrain Ethiopia Bangladesh Fiji Barbados Finland* Belarus France* Belgium Gabon Belize Gambia Benin Georgia Bhutan Germany* Bolivia (Plurinational State of) Ghana Bosnia and Herzegovina Greece* Botswana Grenada Brazil* Guatemala Brunei Darussalam Guinea Bulgaria Guinea-Bissau Burkina Faso Guyana Burundi Haiti Cabo Verde Honduras Cambodia Hungary Cameroon Iceland Canada* India* Central African Republic Indonesia Chad Iran (Islamic Republic of) Chile Iraq China* Ireland Colombia* Israel Comoros Italy* Congo Jamaica Cook Islands Japan* Costa Rica* Jordan Côte d'Ivoire* Kazakhstan Croatia Kenya Cuba Kiribati Cyprus Kuwait Czechia Kyrgyzstan Democratic People's Republic of Korea Lao People's Democratic Republic *Council Member State Latvia Rwanda Lebanon Saint Kitts and Nevis Lesotho Saint Lucia Liberia Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Libya Samoa Lithuania San Marino Luxembourg Sao Tome and Principe Madagascar Saudi Arabia* Malawi Senegal Malaysia* Serbia Maldives Seychelles Mali Sierra Leone Malta Singapore* Marshall Islands Slovakia Mauritania Slovenia Mauritius Solomon Islands Mexico* Somalia Micronesia (Federated States of) South Africa* Monaco South Sudan Mongolia Spain* Montenegro Sri Lanka Morocco Sudan* Mozambique Suriname Myanmar Sweden -

Physical and Biogeochemical Processes Associated with Upwelling in the Indian Ocean Puthenveettil Narayan

https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-2020-486 Preprint. Discussion started: 9 February 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Reviews and syntheses: Physical and biogeochemical processes associated with upwelling in the 2 Indian Ocean 1* 2 3 4 3 Puthenveettil Narayana Menon Vinayachandran , Yukio Masumoto , Mike Roberts , Jenny Hugget , 5 6 7 8 9 4 Issufo Halo , Abhisek Chatterjee , Prakash Amol , Garuda V. M. Gupta , Arvind Singh , Arnab 10 6 11 12 13 5 Mukherjee , Satya Prakash , Lynnath E. Beckley , Eric Jorden Raes , Raleigh Hood 6 7 1Centre for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, 560012, India 8 9 2 Graduate School of Science, University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan 10 11 3 Nelson Mandela University, Port Elizabeth, South Africa 12 13 4Oceans and Coasts Research, Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries, Private Bag X4390, Cape Town 8000, 14 South Africa 15 16 5Department of Conservation and Marine Sciences, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, PO Box 652, Cape Town 17 8000, South Africa 18 6Indian National Centre for Indian Ocean Services, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Hyderabad, India 19 20 7CSIR-National Institute of Oceanography, Regional Centre, Visakhapatnam, 530017, India 21 22 8Centre for Marine Living Resources and Ecology, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Kochi, India 23 24 9Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmedabad, 380009, India 25 26 10 National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research, Ministry of Earth Sciences, Goa, India 27 28 11 Environmental and Conservation Sciences, Murdoch University, Perth, Western Australia 6150, Australia 29 30 12 CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, GPO Box 1538, Hobart, TAS, 7001 Australia 31 32 13 University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, Cambridge, MD, USA 33 34 *Correspondence to: P. -

Chapter 11 the Indian Ocean We Now Turn to the Indian Ocean, Which Is

Chapter 11 The Indian Ocean We now turn to the Indian Ocean, which is in several respects very different from the Pacific Ocean. The most striking difference is the seasonal reversal of the monsoon winds and its effects on the ocean currents in the northern hemisphere. The abs ence of a temperate and polar region north of the equator is another peculiarity with far-reaching consequences for the circulation and hydrology. None of the leading oceanographic research nations shares its coastlines with the Indian Ocean. Few research vessels entered it, fewer still spent much time in it. The Indian Ocean is the only ocean where due to lack of data the truly magnificent textbook of Sverdrup et al. (1942) missed a major water mass - the Australasian Mediterranean Water - completely. The situation did not change until only thirty years ago, when over 40 research vessels from 25 nations participated in the International Indian Ocean Expedition (IIOE) during 1962 - 1965. Its data were compiled and interpreted in an atlas (Wyrtki, 1971, reprinted 1988) which remains the major reference for Indian Ocean research. Nevertheless, important ideas did not exist or were not clearly expressed when the atlas was prepared, and the hydrography of the Indian Ocean still requires much study before a clear picture will emerge. Long-term current meter moorings were not deployed until two decades ago, notably during the INDEX campaign of 1976 - 1979; until then, the study of Indian Ocean dynamics was restricted to the analysis of ship drift data and did not reach below the surface layer. Bottom topography The Indian Ocean is the smallest of all oceans (including the Southern Ocean). -

In Situ Measured Current Structures of the Eddy Field in the Mozambique Channel

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259138771 In situ measured current structures of the eddy field in the Mozambique Channel Article in Deep Sea Research Part II Topical Studies in Oceanography · January 2013 DOI: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.10.013 CITATIONS READS 19 53 5 authors, including: Jean-François Ternon Michael Roberts Institute of Research for Development Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University 31 PUBLICATIONS 557 CITATIONS 74 PUBLICATIONS 1,312 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE L. Hancke B. C. Backeberg 4 PUBLICATIONS 99 CITATIONS Council for Scientific and Industrial Research… 25 PUBLICATIONS 203 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Ocean data assimilation in support of marine research and operational oceanography in South Africa View project Western Indian Ocean Upwelling Research Initiative (WIOURI), part of the Second International Indian Ocean Expedition (IIO2) View project All content following this page was uploaded by Michael Roberts on 20 May 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. All in-text references underlined in blue are added to the original document and are linked to publications on ResearchGate, letting you access and read them immediately. Deep-Sea Research II 100 (2014) 10–26 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Deep-Sea Research II journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dsr2 In situ measured current structures of the eddy field -

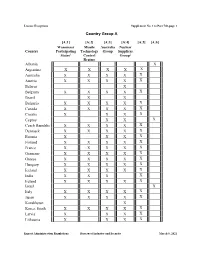

Supplement No. 1 to Part 740•Page 1

License Exceptions Supplement No. 1 to Part 740•page 1 Country Group A [A:1] [A:2] [A:3] [A:4] [A:5] [A:6] Wassenaar Missile Australia Nuclear Country Participating Technology Group Suppliers States1 Control Group2 Regime Albania X X Argentina X X X X X Australia X X X X X Austria X X X X Belarus X X Belgium X X X X Brazil X X X Bulgaria X X X X X Canada X X X X X Croatia X X X X Cyprus X X X Czech Republic X X X X X Denmark X X X X X Estonia X X X X Finland X X X X X France X X X X X Germany X X X X X Greece X X X X X Hungary X X X X X Iceland X X X X X India X X X X Ireland X X X X Israel X X Italy X X X X X Japan X X X X Kazakhstan X X Korea, South X X X X X Latvia X X X Lithuania X X X X Export Administration Regulations Bureau of Industry and Security March 8, 2021 License Exceptions Supplement No. 1 to Part 740•page 2 [A:1] [A:2] [A:3] [A:4] [A:5] [A:6] Wassenaar Missile Australia Nuclear Country Participating Technology Group Suppliers States1 Control Group2 Regime X Luxembourg X X X X X Malta X X X Mexico X X X X Netherlands X X X X X New Zealand X X X X X Norway X X X X X Poland X X X X X Portugal X X X X X Romania X X X Russia1,2,3 Serbia X Singapore X Slovakia X X X X X X X Slovenia X South Africa X X X X X X X X X Spain Sweden X X X X X X X X X Switzerland X Taiwan X X X X X X Turkey Ukraine4 X X X X X X X X United Kingdom United States X X X X 1 Country Group A:1 is a list of the Wassenaar Arrangement Participating States, except for Malta, Russia and Ukraine.