Supreme Court of the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morlock Night Free

FREE MORLOCK NIGHT PDF K. W. Jeter | 332 pages | 26 Apr 2011 | Watkins Media | 9780857661005 | English | London, United Kingdom Morlock Night by K. W. Jeter: | : Books Having acquired a device for themselves, the brutish Morlocks return from the desolate far future to Victorian England to cause mayhem and disruption. But the mythical heroes of Old England have also returned, in the hour of the country's greatest need, to stand between England and her total destruction. Search books and Morlock Night. View all online retailers Find local retailers. Also by KW Jeter. Praise for Morlock Night. Related titles. A Deadly Education. Roald Morlock NightQuentin Blake. The Night Circus. Philip PullmanChristopher Wormell. D A Tale of Two Morlock Night. Good Omens. Neil GaimanTerry Pratchett. His Dark Materials. Trial of the Wizard King. Star Wars: Victory's Price. Violet Black. Beneath the Keep. The Absolute Book. The Morlock Night Devil. The Stranger Times. The Ruthless Lady's Guide to Wizardry. The Orville Season 2. The Bitterwine Oath. Our top books, exclusive content and competitions. Straight to your inbox. Sign Morlock Night to our newsletter using your email. Enter your email to sign up. Thank you! Your subscription to Read More was successful. To help us recommend your next book, tell us what you enjoy reading. Add your interests. Morlock Night - Wikipedia Morlock Night acquired a Morlock Night for themselves, the brutish Morlocks return from the desolate far future to Victorian England to cause mayhem and disruption. When you buy a book, we donate a book. Sign in. Halloween Books for Kids. Morlock Night By K. -

Exhibition Hall

exhibition hall 15 the weird west exhibition hall - november 2010 chris garcia - editor, ariane wolfe - fashion editor james bacon - london bureau chief, ric flair - whooooooooooo! contact can be made at [email protected] Well, October was one of the stronger months for Steampunk in the public eye. No conventions in October, which is rare these days, but there was the Steampunk Fortnight on Tor.com. They had some seriously good stuff, including writing from Diana Vick, who also appears in these pages, and myself! There was a great piece from Nisi Shawl that mentioned the amazing panel that she, Liz Gorinsky, Michael Swanwick and Ann VanderMeer were on at World Fantasy last year. Jaymee Goh had a piece on Commodification and Post-Modernism that was well-written, though slightly troubling to me. Stephen Hunt’s Steampunk Timeline was good stuff, and the omnipresent GD Falksen (who has never written for us!) had a couple of good piece. Me? I wrote an article about how Tomorrowland was the signpost for the rise of Steampunk. You can read it at http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/10/goodbye-tomorrow- hello-yesterday. The second piece is all about an amusement park called Gaslight in New Orleans. I’ll let you decide about that one - http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/10/gaslight- amusement. The final one all about The Cleveland Steamers. This much attention is a good thing for Steampunk, especially from a site like Tor.com, a gateway for a lot of SF readers who aren’t necessarily a part of fandom. -

Morlock Night Download Free (EPUB, PDF)

Morlock Night Download Free (EPUB, PDF) Just what happened when the Time Machine returned? Having acquired a device for themselves, the brutish Morlocks return from the desolate far future to Victorian England to cause mayhem and disruption. But the mythical heroes of Old England have also returned, in the hour of the country's greatest need, to stand between England and her total destruction. Audible Audio Edition Listening Length: 6 hours and 34 minutes Program Type: Audiobook Version: Unabridged Publisher: Angry Robot on Brilliance Audio Audible.com Release Date: March 6, 2013 Language: English ASIN: B00BPX9TTE Best Sellers Rank: #94 in Books > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Fantasy > Gaslamp #1379 in Books > Science Fiction & Fantasy > Science Fiction > Steampunk #5857 in Books > Audible Audiobooks > Science Fiction K.W. Jeter in a 1987 letter to the Locus coined the phrase steampunk. Thus, this work of his published in 1979 raises quite a bar of expectation. In addition, the book is a supposed continuation of H.G. Wells' Time Machine, so you have a considerable level of hype developed. Unfortunately, the book will not suit those looking for a more in depth political analysis. The story is simple and short. Basically, the Morlocks get the Time Machine and plan an invasion of 19th century London. They are stopped in their tracks by the heroic King Arthur with his ever loyal mage, Merlin. The End. The ending its self is quite abrupt and comes right after the twist. All in all, the book is okay, but don't get too thrilled. -

Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by TopSCHOLAR Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-1-2013 Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N. Bergman Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Bergman, Cassie N., "Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature" (2013). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1266. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLOCKWORK HEROINES: FEMALE CHARACTERS IN STEAMPUNK LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts By Cassie N. Bergman August 2013 To my parents, John and Linda Bergman, for their endless support and love. and To my brother Johnny—my best friend. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Johnny for agreeing to continue our academic careers at the same university. I hope the white squirrels, International Fridays, random road trips, movie nights, and “get out of my brain” scenarios made the last two years meaningful. Thank you to my parents for always believing in me. A huge thank you to my family members that continue to support and love me unconditionally: Krystle, Dee, Jaime, Ashley, Lauren, Jeremy, Rhonda, Christian, Anthony, Logan, and baby Parker. -

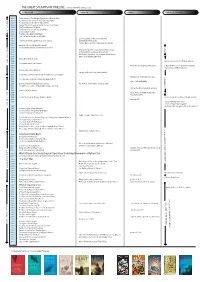

Download the Timeline and Follow Along

THE GREAT STEAMPUNK TIMELINE (to be printed A3 portrait size) LITERATURE FILM & TV GAMES PARALLEL TRACKS 1818 - Frankenstein: or The Modern Prometheus (Mary Shelley) 1864 - A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (Jules Verne) K N 1865 - From the Earth to the Moon (Jules Verne) U P 1869 - Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (Jules Verne) - O 1895 - The Time Machine (HG Wells) T O 1896 - The Island of Doctor Moreau (HG Wells) R P 1897 - Dracula (Bram Stoker) 1898 - The War of the Worlds (HG Wells) 1901 - The First Men in the Moon (HG Wells) 1954 - 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Disney) 1965 - The Wolves of Willoughby Chase (Joan Aiken) The Wild Wild West (CBS) 1969 - Captain Nemo and the Underwater City (MGM) 1971 - Warlord of the Air (Michael Moorcock) 1973 - A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! (Harry Harrison) K E N G 1975 - The Land That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) U A 1976 - At the Earth's Core (Amicus Productions) P S S 1977 - The People That Time Forgot (Amicus Productions) A R 1978 - Warlords of Atlantis (EMI Films) B Y 1979 - Morlock Night (K. W. Jeter) L R 1982 - Burning Chrome, Omni (William Gibson) A E 1983 - The Anubis Gates (Tim Powers) 1983 - Warhammer Fantasy tabletop game > Bruce Bethke coins 'Cyberpunk' (Amazing) 1984 - Neuromancer (William Gibson) 1986 - Homunculus (James Blaylock) 1986 - Laputa Castle in the Sky (Studio Ghibli) 1987 - > K. W. Jeter coins term 'steampunk' in a letter to Locus magazine -

THE MACHINE ANXIETIES of STEAMPUNK: CONTEMPORARY PHILOSOPHY, NEO-VICTORIAN AESTHETICS, and FUTURISM Kathe Hicks Albrecht IDSVA

Maine State Library Maine State Documents Academic Research and Dissertations Special Collections 2016 THE MACHINE ANXIETIES OF STEAMPUNK: CONTEMPORARY PHILOSOPHY, NEO-VICTORIAN AESTHETICS, AND FUTURISM Kathe Hicks Albrecht IDSVA Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/academic Recommended Citation Albrecht, Kathe Hicks, "THE MACHINE ANXIETIES OF STEAMPUNK: CONTEMPORARY PHILOSOPHY, NEO- VICTORIAN AESTHETICS, AND FUTURISM" (2016). Academic Research and Dissertations. 16. http://digitalmaine.com/academic/16 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at Maine State Documents. It has been accepted for inclusion in Academic Research and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Maine State Documents. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MACHINE ANXIETIES OF STEAMPUNK: CONTEMPORARY PHILOSOPHY, NEO-VICTORIAN AESTHETICS, AND FUTURISM Kathe Hicks Albrecht Submitted to the faculty of The Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy July, 2016 i Accepted by the faculty of the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Donald R. Wehrs, Ph.D. Doctoral Committee ______________________________ Other member’s name, #1 Ph.D. ______________________________ Other member’s name, #2, Ph.D. July 23, 2016 ii © 2016 Kathe Hicks Albrecht ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii This work is dedicated to my parents: Dr. Richard Brian Hicks, whose life-long exploration of the human mind and spirit helped to prepare me for my own intellectual journey, and Mafalda Brasile Hicks, artist-philosopher, who originally inspired my deep interest in aesthetics. -

Technofantasies in a Neo-Victorian Retrofuture

University of Alberta The Steampunk Aesthetic: Technofantasies in a Neo-Victorian Retrofuture by Mike Dieter Perschon A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Comparative Literature © Mike Dieter Perschon Fall 2012 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Dedicated to Jenica, Gunnar, and Dacy Abstract Despite its growing popularity in books, film, games, fashion, and décor, a suitable definition for steampunk remains elusive. Debates in online forums seek to arrive at a cogent definition, ranging from narrowly restricting and exclusionary definitions, to uselessly inclusive indefinitions. The difficulty in defining steampunk stems from the evolution of the term as a literary sub-genre of science fiction (SF) to a sub-culture of Goth fashion, Do-It-Yourself (DIY) arts and crafts movements, and more recently, as ideological counter-culture. Accordingly, defining steampunk unilaterally is challenged by what aspect of steampunk culture is being defined. -

Alternate World Building: Retrofuturism and Retrophilia in Steampunk and Dieselpunk Narratives”

Ramos, Iolanda. “Alternate World Building: Retrofuturism and Retrophilia in Steampunk and Dieselpunk Narratives”. Anglo Saxonica, No. 17, issue 1, art. 5, 2020, pp. 1–7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/as.23 RESEARCH Alternate World Building: Retrofuturism and Retrophilia in Steampunk and Dieselpunk Narratives Iolanda Ramos Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas — NOVA FCSH, PT [email protected] This essay draws on William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s steampunk and alternate history novel The Difference Engine (1990) and Len Deighton’s dieselpunk and alternate history thriller SS-GB (1978) for the purpose of discussing the blurring of genres within speculative fiction and addressing retrofuturism and retrophilia within an alternate world building framework. Thus, it provides a background for the analysis of the concept of genre blending and the merging of pre-determined tropes and topics within the scope of science fiction, fantasy, adventure and mystery plots so as to characterize alternate history as a blended genre. Keywords: Alternate history; dieselpunk; speculative fiction; steampunk; retrofuturism This essay aims to discuss the blurring of genres within speculative fiction by means of examining how alter- nate history is deployed in steampunk and dieselpunk narratives. It begins by providing a background for the analysis of the concept of genre blending and the merging of pre- determined tropes and topics within the scope of science fiction, fantasy, adventure and mystery plots so as to characterize alternate history as a blended genre. It continues by focusing on The Difference Engine (1990) as a steampunk and alternate his- tory novel set in a technologically developed Victorian Britain. -

Lesson 3: 20Th Century Steampunk

LESSON 3: 20TH CENTURY STEAMPUNK We talked a bit about Steampunk’s roots with Verne and Wells and their contemporaries. Now let’s look at 20th Steampunk, when this style of speculative fiction came into its own as a sub-genre and then we’ll move on to modern-day Steampunk Before the 20th century, what we know as Steampunk stories today didn’t have a name. And without a name, how will bookstores stock it? Steampunk-with-no-name stories were shelved alongside other Speculative Fiction stories and often lost in the wide variation of sub-genres that Spec Fic allows. STEAMPUNK’S BIRTHDAY This is an excellent quote and I couldn’t say it any better, so I quoted it here for you, a solid definition of Steampunk. I won’t go into a deluge of information “Steampunk is a sub-categorization of about the development of Speculative science fiction in which the predominant Fiction in this class but there are a few technology is steam-based power. things that we must know to become Steampunk stories are usually (but not Steampunk writers with style and one, always) set in the 19th century, and often is the name, K. W. Jeter. in Victoria-era London. The predominant driving force behind steampunk is fun, so the stories usually offer less rigorous .) science than straightforward science fiction.” STEAMPUNK UPDATE, i PART 1—FOLLOWING UP The actual term for Steampunk was created by Speculative Fiction author K. W. Jeter in April 1987 in Locus Magazine. Please read: Birth of Steampunk. I’m not sure how well Jeter is known outside the Spec Fic community. -

Steampunk Novels

Steampunk Must Reads The Affinity Bridge by George Mann: Welcome to the bizarre and dangerous world of Victorian London, a city teetering on the edge of revolution. Its people are ushering in a new era of technology, dazzled each day by new inventions. When an airship crashes in mysterious circumstances, Sir Maurice and his recently appointed assistant Miss Veronica Hobbes are called in to investigate. The Alchemy of Stone by Ekaterina Sedia: Urban fantasy meets steampunk in this novel about a proletarian revolution in a city-state. Anno Dracula by Kim Newman: An alternate history of Bram Stoker’s Dracula where he survives and marries Queen Victoria. The Anubis Gates by Tim Powers: Brendan Doyle, a specialist in the work of the early-nineteenth century poet William Ashbless, reluctantly accepts an invitation from a millionaire to act as a guide to time- travelling tourists. The Difference Engine by William Gibson: In 1855, the Industrial Revolution is in full and inexorable swing, powered by steam-driven cybernetic Engines. Charles Babbage perfects his Analytical Engine and the computer age arrives--a century ahead of its time. Mainspring by Jay Lake (local author): A clockmaker’s apprentice is visited by an angel and asked to wind the mainspring of the Earth. Morlock Night by K.W. Jeter: JUST WHAT HAPPENED WHEN THE TIME MACHINE RETURNED? Having acquired a device for themselves, the brutish Morlocks return from the desolate far future to Victorian England to cause mayhem and disruption. But the mythical heroes of Old England have also returned, in the hour of the country's greatest need, to stand between England and her total destruction. -

Narratives of Victorian Steam Technology Rachel D

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research Summer 2016 Seen Through Steam: Narratives of Victorian Steam Technology Rachel D. Anderson University of Puget Sound, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Rachel D., "Seen Through Steam: Narratives of Victorian Steam Technology" (2016). Summer Research. Paper 268. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/268 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEEN THROUGH STEAM Narratives of Victorian Steam Technology SEPTEMBER 13, 2016 RESEARCH BY RACHEL ANDERSON Advised by Professor Amy Fisher, Science Technology and Society, University of Puget Sound 1 “We all have choices about how we interact with technology and the choices we make not only reflect our values, but influence our values.”1 – Sarah Chrisman (2016) To Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, steam locomotives gave Watson a “swift and pleasant”2 journey to Baskerville Hall. To Charles Dickens, the introduction of the Railway was like, “the first shock of a great earthquake had, just at that period, rent the whole neighbourhood to its centre.”3 These narratives come out of the Victorian era, but in no way mark the end of considerations regarding steam. Modern Steampunk enthusiasts -

Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-2013 Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature Cassie N. Bergman Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Bergman, Cassie N., "Clockwork Heroines: Female Characters in Steampunk Literature" (2013). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1266. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1266 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLOCKWORK HEROINES: FEMALE CHARACTERS IN STEAMPUNK LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bowling Green Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts By Cassie N. Bergman August 2013 To my parents, John and Linda Bergman, for their endless support and love. and To my brother Johnny—my best friend. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Johnny for agreeing to continue our academic careers at the same university. I hope the white squirrels, International Fridays, random road trips, movie nights, and “get out of my brain” scenarios made the last two years meaningful. Thank you to my parents for always believing in me. A huge thank you to my family members that continue to support and love me unconditionally: Krystle, Dee, Jaime, Ashley, Lauren, Jeremy, Rhonda, Christian, Anthony, Logan, and baby Parker.