Physical Characteristics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electrostatics Voltage Source

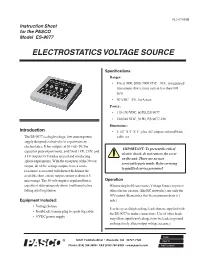

012-07038B Instruction Sheet for the PASCO Model ES-9077 ELECTROSTATICS VOLTAGE SOURCE Specifications Ranges: • Fixed 1000, 2000, 3000 VDC ±10%, unregulated (maximum short circuit current less than 0.01 mA). • 30 VDC ±5%, 1mA max. Power: • 110-130 VDC, 60 Hz, ES-9077 • 220/240 VDC, 50 Hz, ES-9077-220 Dimensions: Introduction • 5 1/2” X 5” X 1”, plus AC adapter and red/black The ES-9077 is a high voltage, low current power cable set supply designed exclusively for experiments in electrostatics. It has outputs at 30 volts DC for IMPORTANT: To prevent the risk of capacitor plate experiments, and fixed 1 kV, 2 kV, and electric shock, do not remove the cover 3 kV outputs for Faraday ice pail and conducting on the unit. There are no user sphere experiments. With the exception of the 30 volt serviceable parts inside. Refer servicing output, all of the voltage outputs have a series to qualified service personnel. resistance associated with them which limit the available short-circuit output current to about 8.3 microamps. The 30 volt output is regulated but is Operation capable of delivering only about 1 milliamp before When using the Electrostatics Voltage Source to power falling out of regulation. other electric circuits, (like RC networks), use only the 30V output (Remember that the maximum drain is 1 Equipment Included: mA.). • Voltage Source Use the special high-voltage leads that are supplied with • Red/black, banana plug to spade lug cable the ES-9077 to make connections. Use of other leads • 9 VDC power supply may allow significant leakage from the leads to ground and negatively affect output voltage accuracy. -

The Lorentz Force

CLASSICAL CONCEPT REVIEW 14 The Lorentz Force We can find empirically that a particle with mass m and electric charge q in an elec- tric field E experiences a force FE given by FE = q E LF-1 It is apparent from Equation LF-1 that, if q is a positive charge (e.g., a proton), FE is parallel to, that is, in the direction of E and if q is a negative charge (e.g., an electron), FE is antiparallel to, that is, opposite to the direction of E (see Figure LF-1). A posi- tive charge moving parallel to E or a negative charge moving antiparallel to E is, in the absence of other forces of significance, accelerated according to Newton’s second law: q F q E m a a E LF-2 E = = 1 = m Equation LF-2 is, of course, not relativistically correct. The relativistically correct force is given by d g mu u2 -3 2 du u2 -3 2 FE = q E = = m 1 - = m 1 - a LF-3 dt c2 > dt c2 > 1 2 a b a b 3 Classically, for example, suppose a proton initially moving at v0 = 10 m s enters a region of uniform electric field of magnitude E = 500 V m antiparallel to the direction of E (see Figure LF-2a). How far does it travel before coming (instanta> - neously) to rest? From Equation LF-2 the acceleration slowing the proton> is q 1.60 * 10-19 C 500 V m a = - E = - = -4.79 * 1010 m s2 m 1.67 * 10-27 kg 1 2 1 > 2 E > The distance Dx traveled by the proton until it comes to rest with vf 0 is given by FE • –q +q • FE 2 2 3 2 vf - v0 0 - 10 m s Dx = = 2a 2 4.79 1010 m s2 - 1* > 2 1 > 2 Dx 1.04 10-5 m 1.04 10-3 cm Ϸ 0.01 mm = * = * LF-1 A positively charged particle in an electric field experiences a If the same proton is injected into the field perpendicular to E (or at some angle force in the direction of the field. -

Quantum Mechanics Electromotive Force

Quantum Mechanics_Electromotive force . Electromotive force, also called emf[1] (denoted and measured in volts), is the voltage developed by any source of electrical energy such as a batteryor dynamo.[2] The word "force" in this case is not used to mean mechanical force, measured in newtons, but a potential, or energy per unit of charge, measured involts. In electromagnetic induction, emf can be defined around a closed loop as the electromagnetic workthat would be transferred to a unit of charge if it travels once around that loop.[3] (While the charge travels around the loop, it can simultaneously lose the energy via resistance into thermal energy.) For a time-varying magnetic flux impinging a loop, theElectric potential scalar field is not defined due to circulating electric vector field, but nevertheless an emf does work that can be measured as a virtual electric potential around that loop.[4] In a two-terminal device (such as an electrochemical cell or electromagnetic generator), the emf can be measured as the open-circuit potential difference across the two terminals. The potential difference thus created drives current flow if an external circuit is attached to the source of emf. When current flows, however, the potential difference across the terminals is no longer equal to the emf, but will be smaller because of the voltage drop within the device due to its internal resistance. Devices that can provide emf includeelectrochemical cells, thermoelectric devices, solar cells and photodiodes, electrical generators,transformers, and even Van de Graaff generators.[4][5] In nature, emf is generated whenever magnetic field fluctuations occur through a surface. -

Measuring Electricity Voltage Current Voltage Current

Measuring Electricity Electricity makes our lives easier, but it can seem like a mysterious force. Measuring electricity is confusing because we cannot see it. We are familiar with terms such as watt, volt, and amp, but we do not have a clear understanding of these terms. We buy a 60-watt lightbulb, a tool that needs 120 volts, or a vacuum cleaner that uses 8.8 amps, and dont think about what those units mean. Using the flow of water as an analogy can make Voltage electricity easier to understand. The flow of electrons in a circuit is similar to water flowing through a hose. If you could look into a hose at a given point, you would see a certain amount of water passing that point each second. The amount of water depends on how much pressure is being applied how hard the water is being pushed. It also depends on the diameter of the hose. The harder the pressure and the larger the diameter of the hose, the more water passes each second. The flow of electrons through a wire depends on the electrical pressure pushing the electrons and on the Current cross-sectional area of the wire. The flow of electrons can be compared to the flow of Voltage water. The water current is the number of molecules flowing past a fixed point; electrical current is the The pressure that pushes electrons in a circuit is number of electrons flowing past a fixed point. called voltage. Using the water analogy, if a tank of Electrical current (I) is defined as electrons flowing water were suspended one meter above the ground between two points having a difference in voltage. -

Calculating Electric Power

Calculating electric power We've seen the formula for determining the power in an electric circuit: by multiplying the voltage in "volts" by the current in "amps" we arrive at an answer in "watts." Let's apply this to a circuit example: In the above circuit, we know we have a battery voltage of 18 volts and a lamp resistance of 3 Ω. Using Ohm's Law to determine current, we get: Now that we know the current, we can take that value and multiply it by the voltage to determine power: Answer: the lamp is dissipating (releasing) 108 watts of power, most likely in the form of both light and heat. Let's try taking that same circuit and increasing the battery voltage to see what happens. Intuition should tell us that the circuit current will increase as the voltage increases and the lamp resistance stays the same. Likewise, the power will increase as well: Now, the battery voltage is 36 volts instead of 18 volts. The lamp is still providing 3 Ω of electrical resistance to the flow of electrons. The current is now: This stands to reason: if I = E/R, and we double E while R stays the same, the current should double. Indeed, it has: we now have 12 amps of current instead of 6. Now, what about power? Notice that the power has increased just as we might have suspected, but it increased quite a bit more than the current. Why is this? Because power is a function of voltage multiplied by current, and both voltage and current doubled from their previous values, the power will increase by a factor of 2 x 2, or 4. -

Electromotive Force

Voltage - Electromotive Force Electrical current flow is the movement of electrons through conductors. But why would the electrons want to move? Electrons move because they get pushed by some external force. There are several energy sources that can force electrons to move. Chemical: Battery Magnetic: Generator Light (Photons): Solar Cell Mechanical: Phonograph pickup, crystal microphone, antiknock sensor Heat: Thermocouple Voltage is the amount of push or pressure that is being applied to the electrons. It is analogous to water pressure. With higher water pressure, more water is forced through a pipe in a given time. With higher voltage, more electrons are pushed through a wire in a given time. If a hose is connected between two faucets with the same pressure, no water flows. For water to flow through the hose, it is necessary to have a difference in water pressure (measured in psi) between the two ends. In the same way, For electrical current to flow in a wire, it is necessary to have a difference in electrical potential (measured in volts) between the two ends of the wire. A battery is an energy source that provides an electrical difference of potential that is capable of forcing electrons through an electrical circuit. We can measure the potential between its two terminals with a voltmeter. Water Tank High Pressure _ e r u e s g s a e t r l Pump p o + v = = t h g i e h No Pressure Figure 1: A Voltage Source Water Analogy. In any case, electrostatic force actually moves the electrons. -

Electromagnetic Induction, Ac Circuits, and Electrical Technologies 813

CHAPTER 23 | ELECTROMAGNETIC INDUCTION, AC CIRCUITS, AND ELECTRICAL TECHNOLOGIES 813 23 ELECTROMAGNETIC INDUCTION, AC CIRCUITS, AND ELECTRICAL TECHNOLOGIES Figure 23.1 This wind turbine in the Thames Estuary in the UK is an example of induction at work. Wind pushes the blades of the turbine, spinning a shaft attached to magnets. The magnets spin around a conductive coil, inducing an electric current in the coil, and eventually feeding the electrical grid. (credit: phault, Flickr) 814 CHAPTER 23 | ELECTROMAGNETIC INDUCTION, AC CIRCUITS, AND ELECTRICAL TECHNOLOGIES Learning Objectives 23.1. Induced Emf and Magnetic Flux • Calculate the flux of a uniform magnetic field through a loop of arbitrary orientation. • Describe methods to produce an electromotive force (emf) with a magnetic field or magnet and a loop of wire. 23.2. Faraday’s Law of Induction: Lenz’s Law • Calculate emf, current, and magnetic fields using Faraday’s Law. • Explain the physical results of Lenz’s Law 23.3. Motional Emf • Calculate emf, force, magnetic field, and work due to the motion of an object in a magnetic field. 23.4. Eddy Currents and Magnetic Damping • Explain the magnitude and direction of an induced eddy current, and the effect this will have on the object it is induced in. • Describe several applications of magnetic damping. 23.5. Electric Generators • Calculate the emf induced in a generator. • Calculate the peak emf which can be induced in a particular generator system. 23.6. Back Emf • Explain what back emf is and how it is induced. 23.7. Transformers • Explain how a transformer works. • Calculate voltage, current, and/or number of turns given the other quantities. -

Chapter 22 Magnetism

Chapter 22 Magnetism 22.1 The Magnetic Field 22.2 The Magnetic Force on Moving Charges 22.3 The Motion of Charged particles in a Magnetic Field 22.4 The Magnetic Force Exerted on a Current- Carrying Wire 22.5 Loops of Current and Magnetic Torque 22.6 Electric Current, Magnetic Fields, and Ampere’s Law Magnetism – Is this a new force? Bar magnets (compass needle) align themselves in a north-south direction. Poles: Unlike poles attract, like poles repel Magnet has NO effect on an electroscope and is not influenced by gravity Magnets attract only some objects (iron, nickel etc) No magnets ever repel non magnets Magnets have no effect on things like copper or brass Cut a bar magnet-you get two smaller magnets (no magnetic monopoles) Earth is like a huge bar magnet Figure 22–1 The force between two bar magnets (a) Opposite poles attract each other. (b) The force between like poles is repulsive. Figure 22–2 Magnets always have two poles When a bar magnet is broken in half two new poles appear. Each half has both a north pole and a south pole, just like any other bar magnet. Figure 22–4 Magnetic field lines for a bar magnet The field lines are closely spaced near the poles, where the magnetic field B is most intense. In addition, the lines form closed loops that leave at the north pole of the magnet and enter at the south pole. Magnetic Field Lines If a compass is placed in a magnetic field the needle lines up with the field. -

Equivalence of Current–Carrying Coils and Magnets; Magnetic Dipoles; - Law of Attraction and Repulsion, Definition of the Ampere

GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) THE EARTH'S MAGNETIC FIELD OUTLINE Magnetism Magnetic forces: - equivalence of current–carrying coils and magnets; magnetic dipoles; - law of attraction and repulsion, definition of the ampere. Magnetic fields: - magnetic fields from electrical currents and magnets; magnetic induction B and lines of magnetic induction. The geomagnetic field The magnetic elements: (N, E, V) vector components; declination (azimuth) and inclination (dip). The external field: diurnal variations, ionospheric currents, magnetic storms, sunspot activity. The internal field: the dipole and non–dipole fields, secular variations, the geocentric axial dipole hypothesis, geomagnetic reversals, seabed magnetic anomalies, The dynamo model Reasons against an origin in the crust or mantle and reasons suggesting an origin in the fluid outer core. Magnetohydrodynamic dynamo models: motion and eddy currents in the fluid core, mechanical analogues. Background reading: Fowler §3.1 & 7.9.2, Lowrie §5.2 & 5.4 GEOPHYSICS (08/430/0012) MAGNETIC FORCES Magnetic forces are forces associated with the motion of electric charges, either as electric currents in conductors or, in the case of magnetic materials, as the orbital and spin motions of electrons in atoms. Although the concept of a magnetic pole is sometimes useful, it is diácult to relate precisely to observation; for example, all attempts to find a magnetic monopole have failed, and the model of permanent magnets as magnetic dipoles with north and south poles is not particularly accurate. Consequently moving charges are normally regarded as fundamental in magnetism. Basic observations 1. Permanent magnets A magnet attracts iron and steel, the attraction being most marked close to its ends. -

Permanent Magnet Design Guidelines

NOTE(2019): THIS ORGANIZATION (MMPA) IS OBSOLETE! MAGNET GUIDELINES Basic physics of magnet materials II. Design relationships, figures merit and optimizing techniques Ill. Measuring IV. Magnetizing Stabilizing and handling VI. Specifications, standards and communications VII. Bibliography INTRODUCTION This guide is a supplement to our MMPA Standard No. 0100. It relates the information in the Standard to permanent magnet circuit problems. The guide is a bridge between unit property data and a permanent magnet component having a specific size and geometry in order to establish a magnetic field in a given magnetic circuit environment. The MMPA 0100 defines magnetic, thermal, physical and mechanical properties. The properties given are descriptive in nature and not intended as a basis of acceptance or rejection. Magnetic measure- ments are difficult to make and less accurate than corresponding electrical mea- surements. A considerable amount of detailed information must be exchanged between producer and user if magnetic quantities are to be compared at two locations. MMPA member companies feel that this publication will be helpful in allowing both user and producer to arrive at a realistic and meaningful specifica- tion framework. Acknowledgment The Magnetic Materials Producers Association acknowledges the out- standing contribution of Parker to this and designers and manufacturers of products usingpermanent magnet materials. Parker the Technical Consultant to MMPA compiled and wrote this document. We also wish to thank the Standards and Engineering Com- mittee of MMPA which reviewed and edited this document. December 1987 3M July 1988 5M August 1996 December 1998 1 M CONTENTS The guide is divided into the following sections: Glossary of terms and conversion A very important starting point since the whole basis of communication in the magnetic material industry involves measurement of defined unit properties. -

Electric and Magnetic Fields the Facts

PRODUCED BY ENERGY NETWORKS ASSOCIATION - JANUARY 2012 electric and magnetic fields the facts Electricity plays a central role in the quality of life we now enjoy. In particular, many of the dramatic improvements in health and well-being that we benefit from today could not have happened without a reliable and affordable electricity supply. Electric and magnetic fields (EMFs) are present wherever electricity is used, in the home or from the equipment that makes up the UK electricity system. But could electricity be bad for our health? Do these fields cause cancer or any other disease? These are important and serious questions which have been investigated in depth during the past three decades. Over £300 million has been spent investigating this issue around the world. Research still continues to seek greater clarity; however, the balance of scientific evidence to date suggests that EMFs do not cause disease. This guide, produced by the UK electricity industry, summarises the background to the EMF issue, explains the research undertaken with regard to health and discusses the conclusion reached. Electric and Magnetic Fields Electric and magnetic fields (EMFs) are produced both naturally and as a result of human activity. The earth has both a magnetic field (produced by currents deep inside the molten core of the planet) and an electric field (produced by electrical activity in the atmosphere, such as thunderstorms). Wherever electricity is used there will also be electric and magnetic fields. Electric and magnetic fields This is inherent in the laws of physics - we can modify the fields to some are inherent in the laws of extent, but if we are going to use electricity, then EMFs are inevitable. -

Electromagnetic Fields and Energy

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher. Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Please use the following citation format: Haus, Hermann A., and James R. Melcher, Electromagnetic Fields and Energy. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare). http://ocw.mit.edu (accessed [Date]). License: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike. Also available from Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1989. ISBN: 9780132490207. Note: Please use the actual date you accessed this material in your citation. For more information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms 8 MAGNETOQUASISTATIC FIELDS: SUPERPOSITION INTEGRAL AND BOUNDARY VALUE POINTS OF VIEW 8.0 INTRODUCTION MQS Fields: Superposition Integral and Boundary Value Views We now follow the study of electroquasistatics with that of magnetoquasistat ics. In terms of the flow of ideas summarized in Fig. 1.0.1, we have completed the EQS column to the left. Starting from the top of the MQS column on the right, recall from Chap. 3 that the laws of primary interest are Amp`ere’s law (with the displacement current density neglected) and the magnetic flux continuity law (Table 3.6.1). � × H = J (1) � · µoH = 0 (2) These laws have associated with them continuity conditions at interfaces. If the in terface carries a surface current density K, then the continuity condition associated with (1) is (1.4.16) n × (Ha − Hb) = K (3) and the continuity condition associated with (2) is (1.7.6). a b n · (µoH − µoH ) = 0 (4) In the absence of magnetizable materials, these laws determine the magnetic field intensity H given its source, the current density J.