Introduction to Real Estate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State No. Description Size in Cm Date Location

Maps State No. Description Size in cm Date Location National Forests in Alabama. Washington: ALABAMA AL-1 49x28 1989 Map Case US Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service. Bankhead National Forest (Bankhead and Alabama AL-2 66x59 1981 Map Case Blackwater Districts). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Side A : Coronado National Forest (Nogales A: 67x72 ARIZONA AZ-1 1984 Map Case Ranger District). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B: 67x63 Side B : Coronado National Forest (Sierra Vista Ranger District). Side A : Coconino National Forest (North A:69x88 Arizona AZ-2 1976 Map Case Half). Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:69x92 Side B : Coconino National Forest (South Half). Side A : Coronado National Forest (Sierra A:67x72 Arizona AZ-3 1976 Map Case Vista Ranger District. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:67x72 Side B : Coronado National Forest (Nogales Ranger District). Prescott National Forest. Washington: US Arizona AZ-4 28x28 1992 Map Case Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Kaibab National Forest (North Unit). Arizona AZ-5 68x97 1967 Map Case Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Prescott National Forest- Granite Mountain Arizona AZ-6 67x48.5 1993 Map Case Wilderness. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Side A : Prescott National Forest (East Half). A:111x75 Arizona AZ-7 1993 Map Case Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. B:111x75 Side B : Prescott National Forest (West Half). Arizona AZ-8 Superstition Wilderness: Tonto National 55.5x78.5 1994 Map Case Forest. Washington: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Arizona AZ-9 Kaibab National Forest, Gila and Salt River 80x96 1994 Map Case Meridian. -

Manual of Surveying Instructions for the Survey of the Public Lands of The

C^ ^y^^A^ '<L- ^7. /- yf/^. <x^ & :; USo^ TaI : 51 A N U A L OF SURVEYING INSTRUCTIONS FOll THE SUinEY OE THE PUi^LIC LANDS OF THE U:^riTED STATES A^D P^HIA^^TE LA^jSTD CLiS.I]MS. Prepared in conformity witli law nniler the direc'ion of THE COMMISSIONER OP TnE/oEXEKAL LAND OFFICE. JUNE 30, 1S94. WASHINGTON C OTLililN'r-IENT PRINTING 0FFIC3. 1 8 9 i. Department of the Interior, General Land Office, Washington, D. C, June 30, 1894. Gentlemen : The followiug instructions, including full and minute directions for the execution of surveys in the field, are issued under the authority given me by sections 453, 456, and 23!)S, United States Kevised Stat- utes, and must be strictly complied with by yourselves, your office assistants, aud deputy surveyors. All directions in conflict with these instructions are hereby abrogated. In all official communications, this edition will be known and referred to as the Manual of 1S94. Very respectfully, S. W. Lamoreux, Commissioner. To Surveyors General, of the United States. ; MANUAL or SURVEYmG I:N^STRUCT10NS. HISTORY OF LEGISLATION FOR SURVEYS. Tlic present system of survey of the public lands was inau<^urated by a committee appointed by the Continental Congress, consisting of the following delegates: Hon. Thos. Jefferson, Chairman Virginia. Hon. Hugh Williamson ]Srorth Carolina. Hon. David Howell IMiode Island. Hon. Elbridge Gerry Massachusetts. Hon. Jacob Read South Carolina. On the 7th of May, 1784, this committee lepoitcd "An ordinance for ascertaining the mode of locating and (lisi)osiiig of lands in the western territory, and lor other purposes therein mentioned." This ordinance required the public lands to be divided into " hundreds " often geograph- ical miles square, and those again to be subdivided into lots of one mile square each, to be numbered from 1 to 100, commencing in the nortli- tcestern corner, and continuing from west to east and from east to west consecutively. -

Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) This Index Is Color Coded to Indicate Source of Information

Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) This Index is color coded to indicate source of information. H-1275-1 - Manual Land Status Records (Revised Proposed 2001 Edition from Rick Dickman) Oregon/Washington Proposed Abbreviations (Robert DeViney - retired 2006) Oregon/Washington Proposed Abbreviations (Land Records Team - Post Robert DeViney) 1st Prin Mer First Principal Meridian 2nd Prin Mer Second Principal Meridian 3rd Prin Mer Third Principal Meridian 4th Prin Mer Fourth Principal Meridian 5th Prin Mer Fifth Principal Meridian 6th Prin Mer Sixth Principal Meridian 1/2 Half 1/4 Quarter A A A Acre(s) A&M Col Agriculture and Mechanical College A/G Anchors & guys A/Rd Access road ACEC Area of Critical Environmental Concern Acpt Accept/Accepted Acq Acquired Act of Cong Act of Congress ADHE Adjusted homestead entry Adm S Administrative site Admin Administration, administered AEC Atomic Energy Commission AF Air Force Agri Agriculture, Agricultural Agri Exp Sta Agriculture Experiment Station AHA Alaska Housing Authority AHE Additional homestead entry All Min All minerals Allot Allotment Als PS Alaska public sale Amdt Amendment, Amended, Amends Anc Fas Ancillary facilities ANS Air Navigation Site AO Area Office Apln Application Apln Ext Application for extension Aplnt Applicant App Appendix Approp Appropriation, Appropriate, Appropriated Page 1 of 13 Index of Standard Abbreviations (Sorted by Abbreviation) Appvd Approved Area Adm O Area Administrator Order(s) Arpt Airport ARRCS Alaska Rural Rehabilitation Corp. sale Asgn Assignment -

PTAX 1-M, Introduction to Mapping for Assessors

1-M, Introduction to Mapping for Assessors # 001-805 68 PTAX 1-M Rev 02/2021 1 Printed by the authority of the State of Illinois. web only, one copy 2 Table of Contents Glossary ............................................................................................................ Page 5 Where to Get Assistance ................................................................................... Page 10 Unit 1: Basic Types and Uses of Maps ............................................................. Page 13 Unit 2: Measurements and Math for Mapping .................................................. Page 33 Unit 3: The US Rectangular Land Survey ........................................................ Page 49 Unit 4: Legal Descriptions ................................................................................ Page 63 Blank Practice Pages ...................................................................................... Page 94 Unit 5: Metes and Bounds Legal Descriptions .................................................. Page 97 Unit 6: Principles for Assigning Property Index Numbers ................................. Page 131 Unit 7: GIS and Mapping .................................................................................. Page 151 Exam Preparation.............................................................................................. Page 160 Answer Key ....................................................................................................... Page 161 3 4 Glossary Acre – A unit of land area in England -

The Ohio Surveys

Report on Ohio Survey Investigation -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A Report on the Investigation of the FGDC Cadastral Data Content Standard and its Applicability in Support of the Ohio Survey Systems Nancy von Meyer Fairview Industries, Inc For The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) National Integrated Land System (NILS) Project Office January 2005 i Report on Ohio Survey Investigation -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Preface Ohio was the testing and proving grounds of the Public Land Survey System (PLSS). As a result Ohio contains many varied land descriptions and survey systems. Further complicating the Ohio land description scene are large federal tracts reserved for military use and lands held by other states prior to Ohio statehood. This document is not a history of the land system development for Ohio. The history of Ohio surveys can be found in other materials including the following: Downs, Randolf C., 1927, Evolution of Ohio County Boundaries”, Ohio Archeological and Historical Publications Number XXXVI, Columbus, Ohio. Reprinted in 1970. Gates, Paul W., 1968. “History of Public Land Law Development”, Public Land Law Review Commission, Washington DC. Knepper, George, 2002, “The Official Ohio Lands Book” Auditor of State, Columbus Ohio. http://www.auditor.state.oh.us/StudentResources/OhioLands/ohio_lands.pdf Last Accessed November 2, 2004 Petro, Jim, 1997, “Ohio Lands A Short History”, Auditor of State, Columbus Ohio. Sherman, C.E., 1925, “Original Ohio Land Subdivisions” Volume III of the Final Report to the Ohio Cooperative Topographic Survey. Reprinted in 1991. White, Albert C., “A History of the Public Land Survey System”, US Government Printing Office, Stock Number 024-011-00150-6, Washington D.C. -

Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 138 / Wednesday, July 19, 1995 / Notices Assigned Permit Number PRT–804479

37068 Federal Register / Vol. 60, No. 138 / Wednesday, July 19, 1995 / Notices assigned Permit Number PRT±804479. by the Utah prairie dog, a threatened States in the event the patentee or its The requested permit, which is for a species. successor, used the land for purposes period not to exceed 2 years, would The Applicant considered a no action other than that specified in the patent. authorize the incidental take of the alternative. The prairie dogs are situated The land was not improved in threatened Utah prairie dog (Cynomys on the property in such a way that the accordance with the provision of the parvidens). The proposed take would proposed development cannot be plan of development on file with this occur as a result of development of a 33- planned to avoid them. Furthermore, Bureau; therefore, the land reverted acre housing community on privately- this is a small colony surrounded by back to the United States by operation owned property within the city limits of industrial and residential development, of law. Cedar City, Iron County, Utah. and a State highway. Implementation of At 10 a.m. on August 18, 1995, the The Applicant has prepared a habitat the no action alternative would cause land will be opened to the operation of conservation plan and an environmental loss of use of the private property, the public land laws generally, subject assessment for the incidental take resulting in an economic loss. to valid existing rights, the provisions of permit application. This notice is Authority: The authority for this action is existing withdrawals, other segregations provided pursuant to section 10(c) of the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as of record, and the requirements of the Act and National Environmental amended (16 U.S.C. -

Chapter 2 Real Property & the Law Correspondence Course Information

2 Real Property 1 And the Law AlaskaRealEstateSchool.com Chapter 2 Real Property & the Law Correspondence Course Information Please read and become familiar with this information prior to the class date. This part of the class will be taken correspondence. You will be required to take a test on this information and the test must be returned prior to taking the classroom portion of the course. The remainder of the class may be taken in the classroom or by correspondence. If you have registered for the correspondence course, the test as well as the evaluation sheet must returned for grading and issuance of you graduation certificate. You may take the tests all at once or one chapter at a time. The test may be taken open book and the answer sheet must be sent back to: Email to [email protected] Or Fax to 866-659-8458 Or Mail to: AlaskaRealEstateSchool.com Attn: Denny Wood PO Box 241727 Anchorage, Alaska 99524-1727 copyright 2013 dwood 2 Real Property 2 And the Law AlaskaRealEstateSchool.com Property law is the area of law that governs the various forms of ownership in real property (land as distinct from personal or movable possessions) and in personal property, within the common law legal system. In the civil law system, there is a division between movable and immovable property. Movable property roughly corresponds to personal property, while immovable property corresponds to real estate or real property, and the associated rights and obligations thereon. The concept, idea or philosophy of property underlies all property law. In some jurisdictions, historically all property was owned by the monarch and it devolved through feudal land tenure or other feudal systems of loyalty and fealty. -

Cadastral NSDI Reference Document – July 2006

Cadastral NSDI Reference Document – July 2006 Cadastral NSDI Reference Document July 2006 Purpose This document describes the Cadastral NSDI, its components and the public and private business processes that define the content. The Cadastral National Spatial Data Infrastructure (Cadastral NSDI) has been defined by the FGDC Cadastral Subcommittee as a minimum set of attributes about land parcels that is used for publication and distribution of cadastral information by cadastral data producers for use by applications and business processes. The standards for the data content of the Cadastral NSDI are derived from the Cadastral Data Content Standard1, which is a standard for all cadastral elements and extends beyond the minimum elements in the Cadastral NSDI. This standard and many other documents related to the Cadastral NSDI and the Cadastral Subcommittee can be found at http://www.nationalcad.org. Business Applications The goal of the FGDC Cadastral Data Subcommittee is to provide a uniform coverage of parcel data that provides a multi-jurisdictional view or private, state and federal lands, their ownership, use, structures and the value of private property. Figure 1 shows an example of the characteristics of a single parcel and the type of information that would be available for entire region. GIS analysis of a regional coverage allows users to identify the location of properties with specific characteristics within a region. A recent study of the utility of parcel data by emergency responders after a hurricane found that local parcel information was uniquely capable of answering questions that ranged from the identification of vacant lands that could be used for debris removal to the location of organic farms to avoid spraying them with insecticides. -

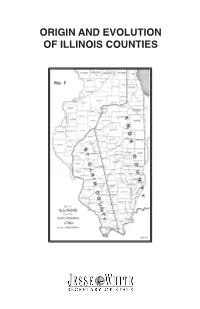

ORIGIN and EVOLUTION of ILLINOIS COUNTIES I PUB 15.10:Layout 1 3/16/10 8:54 AM Page 1

I PUB 15.10:Layout 1 3/16/10 8:54 AM Page 1 ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF ILLINOIS COUNTIES I PUB 15.10:Layout 1 3/16/10 8:54 AM Page 1 ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF ILLINOIS COUNTIES 1 I PUB 15.10:Layout 1 3/16/10 8:54 AM Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and History........................................................................................3 Maps ....................................................................................................................14 Present Map.........................................................................................................59 Origin of County Names .....................................................................................60 JESSE WHITE • Secretary of State Printed by the authority of the State of Illinois. March 2010 — 1 — I Pub 15.10 2 I PUB 15.10:Layout 1 3/16/10 8:54 AM Page 3 COUNTIES OF ILLINOIS St. Clair and Randolph as Counties of Northwest Territory In 1784, Virginia surrendered to the general government all claims to this territory and in 1787 “An Act for the government of the territory of the United States northwest of the Ohio River” was passed by the congress sitting under the articles of confederation. Under this ordi- nance General Arthur St. Clair was appointed governor of the territory, and, in 1790, organized by proclamation, the county of St. Clair, named in honor of himself. To understand the boundaries defined in this and subsequent proclamations, and in early legislative acts setting up counties in the Northwest Territory, Indiana Territory and the terri- tory of Illinois, it is necessary to know the geographical location of a number of points not found on modern maps of Illinois. Some of these points are: The “Little Michilimackinack;” The Mackinaw River flowing into the Illinois four or five miles below Pekin in Tazwell County. -

Federal Register/Vol. 69, No. 196/Tuesday, October 12, 2004

Federal Register / Vol. 69, No. 196 / Tuesday, October 12, 2004 / Notices 60639 Boston Boulevard, Springfield, Virginia stay the filing pending our become final, including decisions on 22153. Attn: Cadastral Survey. consideration of the protest. We will not appeals. SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: This officially file the plat until the day after Dated: September 23, 2004. survey was requested by the U.S. Army we have accepted or dismissed all Stephen D. Douglas, protests and they have become final, Corps of Engineers. Chief Cadastral Surveyor. The lands we surveyed are: including decisions on appeals. [FR Doc. 04–22806 Filed 10–8–04; 8:45 am] Dated: September 28, 2004. Third Principal Meridian, Illinois BILLING CODE 4310–GJ–P T. 3 S., R. 3 E. Stephen D. Douglas, Chief Cadastral Surveyor. The plat of survey represents the [FR Doc. 04–22805 Filed 10–8–04; 8:45 am] DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR survey of an amended portion of the BILLING CODE 4310–GJ–P Rend Lake acquisition boundary, in Bureau of Land Management Township 3 South, Range 3 East, of the Third Principal Meridian, in the State of [ES–960–1430–BJ ES–052327, Group No. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 25, Mississippi] Illinois, and was accepted on September 22, 2004. Bureau of Land Management Eastern States: Filing of Plat of Survey We will place a copy of the plat we described in the open files. It will be [ES–960–1420–BJ–TRST; ES–052442, AGENCY: Bureau of Land Management, Group No. 156, Minnesota] made available to the public as a matter Interior. of information. -

18. Geologic Terms and Geographic Divisions

18. Geologic Terms and Geographic Divisions Geologic terms For capitalization, compounding, and use of quotations in geologic terms, copy is to be followed. Geologic terms quoted verbatim from published ma- terial should be left as the original author used them; however, it should be made clear that the usage is that of the original author. Formal geologic terms are capitalized: Proterozoic Eon, Cambrian Period. Structural terms such as arch, anticline, or uplift are capitalized when pre- ceded by a name: Cincinnati Arch, Cedar Creek Anticline, Ozark Uplift . See Chapter 4 geographic terms for more information. Divisions of Geologic Time [Most recent to oldest] Eon Era Period Phanerozoic ................ Cenozoic ............................ Quarternary. Tertiary (Neogene, Paleogene). Mesozoic........................... Cretaceous. Jurassic. Triassic. Paleozoic .......................... Permian. Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian, Mississippian). Devonian. Silurian. Ordovician. Cambrian. Proterozoic ................. Neoproterozoic ............... Ediacaran. Cryogenian. Tonian. Mesoproterozoic ............. Stenian. Ectasian. Calymmian. Paleoproterozoic ............. Statherian. Orosirian. Rhyacian. Siderian. Archean ....................... Neoarchean. Mesoarchean. Paleoarchean. Eoarchean. Hadean. Source: Information courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey; for graphic see http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2007/3015/ fs2007-3015.pdf. 343 cchapter18.inddhapter18.indd 334343 111/13/081/13/08 3:19:233:19:23 PPMM 344 Chapter 18 Physiographic regions Physiographic -

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 17.95

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Serv., Interior § 17.95 constituent elements within the de- VIRGINIA BIG-EARED BAT (Plecotus townsendii fined area of Critical Habitat that are virginianus) essential to the conservation of the West Virginia. Cave Mountain Cave, species. Those major constituent ele- Hellhole Cave, Hoffman School Cave, and ments that are known to require spe- Sinnit Cave, each in Pendleton County; Cave cial management considerations or Hollow Cave, Tucker County. protection will be listed with the de- NOTE: Map follows: scription of the Critical Habitat. (d) The sequence of species within each list of Critical Habitats in §§ 17.95 and 17.96 will follow the sequences in the lists of Endangered and Threatened wildlife (§ 17.11) and plants (§ 17.12). Multiple entries for each species will be alphabetic by State. [45 FR 13021, Feb. 27, 1980] § 17.95 Critical habitatÐfish and wild- life. (a) Mammals. INDIANA BAT (Myotis sodalis) Illinois. The Blackball Mine, La Salle County. Indiana. Big Wyandotte Cave, Crawford County; Ray's Cave, Greene County. Kentucky. Bat Cave, Carter County; Coach Cave, Edmonson County. FRESNO KANGAROO RAT (Dipodomys nitratoides exilis) Missouri. Cave 021, Crawford County; Cave 009, Franklin County; Cave 017, Franklin California. An area of land, water, and air- County; Pilot Knob Mine, Iron County; Bat space in Fresno County, with the following Cave, Shannon County; Cave 029, Washington components (Mt. Diablo Base Meridian): County (numbers assigned by Division of Ec- T14S R15E, E1¤2 NW1¤4 and NE1¤4 Sec. 11, that ological Services, U.S. Fish and Wildlife part of W1¤2 Sec.