Introduction to Solid State Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Parallelepiped Based Approach

3D Modelling Using Geometric Constraints: A Parallelepiped Based Approach Marta Wilczkowiak, Edmond Boyer, and Peter Sturm MOVI–GRAVIR–INRIA Rhˆone-Alpes, 38330 Montbonnot, France, [email protected], http://www.inrialpes.fr/movi/people/Surname Abstract. In this paper, efficient and generic tools for calibration and 3D reconstruction are presented. These tools exploit geometric con- straints frequently present in man-made environments and allow cam- era calibration as well as scene structure to be estimated with a small amount of user interactions and little a priori knowledge. The proposed approach is based on primitives that naturally characterize rigidity con- straints: parallelepipeds. It has been shown previously that the intrinsic metric characteristics of a parallelepiped are dual to the intrinsic charac- teristics of a perspective camera. Here, we generalize this idea by taking into account additional redundancies between multiple images of multiple parallelepipeds. We propose a method for the estimation of camera and scene parameters that bears strongsimilarities with some self-calibration approaches. Takinginto account prior knowledgeon scene primitives or cameras, leads to simpler equations than for standard self-calibration, and is expected to improve results, as well as to allow structure and mo- tion recovery in situations that are otherwise under-constrained. These principles are illustrated by experimental calibration results and several reconstructions from uncalibrated images. 1 Introduction This paper is about using partial information on camera parameters and scene structure, to simplify and enhance structure from motion and (self-) calibration. We are especially interested in reconstructing man-made environments for which constraints on the scene structure are usually easy to provide. -

Area, Volume and Surface Area

The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 11 AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA A guide for teachers - Years 8–10 June 2011 YEARS 810 Area, Volume and Surface Area (Measurement and Geometry: Module 11) For teachers of Primary and Secondary Mathematics 510 Cover design, Layout design and Typesetting by Claire Ho The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project 2009‑2011 was funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. © The University of Melbourne on behalf of the international Centre of Excellence for Education in Mathematics (ICE‑EM), the education division of the Australian Mathematical Sciences Institute (AMSI), 2010 (except where otherwise indicated). This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‑nc‑nd/3.0/ The Improving Mathematics Education in Schools (TIMES) Project MEASUREMENT AND GEOMETRY Module 11 AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA A guide for teachers - Years 8–10 June 2011 Peter Brown Michael Evans David Hunt Janine McIntosh Bill Pender Jacqui Ramagge YEARS 810 {4} A guide for teachers AREA, VOLUME AND SURFACE AREA ASSUMED KNOWLEDGE • Knowledge of the areas of rectangles, triangles, circles and composite figures. • The definitions of a parallelogram and a rhombus. • Familiarity with the basic properties of parallel lines. • Familiarity with the volume of a rectangular prism. • Basic knowledge of congruence and similarity. • Since some formulas will be involved, the students will need some experience with substitution and also with the distributive law. -

Evaporationin Icparticles

The JapaneseAssociationJapanese Association for Crystal Growth (JACG){JACG) Small Metallic ParticlesProduced by Evaporation in lnert Gas at Low Pressure Size distributions, crystal morphologyand crystal structures KazuoKimoto physiosLaboratory, Department of General Educatien, Nago)ra University Various experimental results ef the studies on fine 1. Introduction particles produced by evaperation and subsequent conden$ation in inert gas at low pressure are reviewed. Small particles of metals and semi-metals can A brief historical survey is given and experimental be produced by evaporation and subsequent arrangements for the production of the particles are condensation in the free space of an inert gas at described. The structure of the stnoke, the qualitative low pressure, a very simple technique, recently particle size clistributions, small particle statistios and "gas often referred to as evaporation technique"i) the crystallographic aspccts ofthe particles are consid- ered in some detail. Emphasis is laid on the crystal (GET). When the pressure of an inert is in the inorphology and the related crystal structures ef the gas range from about one to several tens of Torr, the particles efsome 24 elements. size of the particles produced by GET is in thc range from several to several thousand nm, de- pending on the materials evaporated, the naturc of the inert gas and various other evaporation conditions. One of the most characteristic fea- tures of the particles thus produced is that the particles have, generally speaking, very well- defined crystal habits when the particle size is in the range from about ten to several hundred nm. The crystal morphology and the relevant crystal structures of these particles greatly interested sDme invcstigators in Japan, 4nd encouraged them to study these propenies by means of elec- tron microscopy and electron difliraction. -

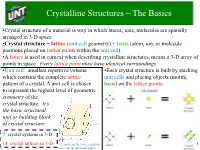

Crystal Structure of a Material Is Way in Which Atoms, Ions, Molecules Are Spatially Arranged in 3-D Space

Crystalline Structures – The Basics •Crystal structure of a material is way in which atoms, ions, molecules are spatially arranged in 3-D space. •Crystal structure = lattice (unit cell geometry) + basis (atom, ion, or molecule positions placed on lattice points within the unit cell). •A lattice is used in context when describing crystalline structures, means a 3-D array of points in space. Every lattice point must have identical surroundings. •Unit cell: smallest repetitive volume •Each crystal structure is built by stacking which contains the complete lattice unit cells and placing objects (motifs, pattern of a crystal. A unit cell is chosen basis) on the lattice points: to represent the highest level of geometric symmetry of the crystal structure. It’s the basic structural unit or building block of crystal structure. 7 crystal systems in 3-D 14 crystal lattices in 3-D a, b, and c are the lattice constants 1 a, b, g are the interaxial angles Metallic Crystal Structures (the simplest) •Recall, that a) coulombic attraction between delocalized valence electrons and positively charged cores is isotropic (non-directional), b) typically, only one element is present, so all atomic radii are the same, c) nearest neighbor distances tend to be small, and d) electron cloud shields cores from each other. •For these reasons, metallic bonding leads to close packed, dense crystal structures that maximize space filling and coordination number (number of nearest neighbors). •Most elemental metals crystallize in the FCC (face-centered cubic), BCC (body-centered cubic, or HCP (hexagonal close packed) structures: Room temperature crystal structure Crystal structure just before it melts 2 Recall: Simple Cubic (SC) Structure • Rare due to low packing density (only a-Po has this structure) • Close-packed directions are cube edges. -

Types of Lattices

Types of Lattices Types of Lattices Lattices are either: 1. Primitive (or Simple): one lattice point per unit cell. 2. Non-primitive, (or Multiple) e.g. double, triple, etc.: more than one lattice point per unit cell. Double r2 cell r1 r2 Triple r1 cell r2 r1 Primitive cell N + e 4 Ne = number of lattice points on cell edges (shared by 4 cells) •When repeated by successive translations e =edge reproduce periodic pattern. •Multiple cells are usually selected to make obvious the higher symmetry (usually rotational symmetry) that is possessed by the 1 lattice, which may not be immediately evident from primitive cell. Lattice Points- Review 2 Arrangement of Lattice Points 3 Arrangement of Lattice Points (continued) •These are known as the basis vectors, which we will come back to. •These are not translation vectors (R) since they have non- integer values. The complexity of the system depends upon the symmetry requirements (is it lost or maintained?) by applying the symmetry operations (rotation, reflection, inversion and translation). 4 The Five 2-D Bravais Lattices •From the previous definitions of the four 2-D and seven 3-D crystal systems, we know that there are four and seven primitive unit cells (with 1 lattice point/unit cell), respectively. •We can then ask: can we add additional lattice points to the primitive lattices (or nets), in such a way that we still have a lattice (net) belonging to the same crystal system (with symmetry requirements)? •First illustrate this for 2-D nets, where we know that the surroundings of each lattice point must be identical. -

The Metrical Matrix in Teaching Mineralogy G. V

THE METRICAL MATRIX IN TEACHING MINERALOGY G. V. GIBBS Department of Geological Sciences & Department of Materials Science and Engineering Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] INTRODUCTION The calculation of the d-spacings, the angles between planes and zones, the bond lengths and angles and other important geometric relationships for a mineral can be a tedious task both for the student and the instructor, particularly when completed with the large as- sortment of trigonometric identities and algebraic formulae that are available (d. Crystal Geometry (1959), Donnay and Donnay, International Tables for Crystallography, Vol. II, Section 3, The Kynoch Press, 101-158). However, such calculations are straightforward and relatively easy to do when completed with the metrical matrix and the interactive software MATOP. Several applications of the matrix are presented below, each of which is worked out in detail and which is designed to teach you its use in the study of crystal geometry. SOME PRELIMINARY COMMENTS We begin our discussion of the matrix with a brief examination of the properties of the geometric three dimensional space, S, in which we live and in which minerals and rocks occur. For our purposes, it will be convenient to view S as the set of all vectors that radiate from a common origin to each point in space. In constructing a model for S, we chose three noncoplanar, coordinate axes denoted X, Y and Z, each radiating from the origin, O. Next, we place three nonzero vectors denoted a, band c along X, Y and Z, respectively, likewise radiating from O. -

Primitive Cell Wigner-Seitz Cell (WS) Primitive Cell

Lecture 4 Jan 16 2013 Primitive cell Primitive cell Wigner-Seitz cell (WS) First Brillouin zone The Wigner-Seitz primitive cell of the reciprocal lattice is known as the first Brillouin zone. (Wigner-Seitz is real space concept while Brillouin zone is a reciprocal space idea). Powder cell Polymorphic Forms of Carbon Graphite – a soft, black, flaky solid, with a layered structure – parallel hexagonal arrays of carbon atoms – weak van der Waal’s forces between layers – planes slide easily over one another Miller indices Simple cubic Miller Indices Rules for determining Miller Indices: 1. Determine the intercepts of the face along the crystallographic axes, in terms of un it ce ll dimens ions. 2. Take the reciprocals 3. Clear fractions 4. Reduce to lowest terms Simple cubic d100=? Where does a protein crystallographer see the Miller indices? CtlCommon crystal faces are parallel to lattice planes • Eac h diffrac tion spo t can be regarded as a X-ray beam reflected from a lattice plane , and therefore has a unique Miller index. Miller indices A Miller index is a series of coprime integers that are inversely ppproportional to the intercepts of the cry stal face or crystallographic planes with the edges of the unit cell. It describes the orientation of a plane in the 3-D lattice with respect to the axes. The general form of the Miller index is (h, k, l) where h, k, and l are integers related to the unit cell along the a, b, c crystal axes. Irreducible brillouin zone II II II II Reciprocal lattice ghakblc The Bravais lattice after Fourier transform real space reciprocal lattice normaltthlls to the planes (vect ors ) poitints spacing between planes 1/distance between points ((y,p)actually, 2p/distance) l (distance, wavelength) 2p/l=k (momentum, wave number) BillBravais cell Wigner-SiSeitz ce ll Brillouin zone . -

Chapter 4, Bravais Lattice Primitive Vectors

Chapter 4, Bravais Lattice A Bravais lattice is the collection of all (and only those) points in space reachable from the origin with position vectors: n , n , n integer (+, -, or 0) r r r r 1 2 3 R = n1a1 + n2 a2 + n3a3 a1, a2, and a3 not all in same plane The three primitive vectors, a1, a2, and a3, uniquely define a Bravais lattice. However, for one Bravais lattice, there are many choices for the primitive vectors. A Bravais lattice is infinite. It is identical (in every aspect) when viewed from any of its lattice points. This is not a Bravais lattice. Honeycomb: P and Q are equivalent. R is not. A Bravais lattice can be defined as either the collection of lattice points, or the primitive translation vectors which construct the lattice. POINT Q OBJECT: Remember that a Bravais lattice has only points. Points, being dimensionless and isotropic, have full spatial symmetry (invariant under any point symmetry operation). Primitive Vectors There are many choices for the primitive vectors of a Bravais lattice. One sure way to find a set of primitive vectors (as described in Problem 4 .8) is the following: (1) a1 is the vector to a nearest neighbor lattice point. (2) a2 is the vector to a lattice points closest to, but not on, the a1 axis. (3) a3 is the vector to a lattice point nearest, but not on, the a18a2 plane. How does one prove that this is a set of primitive vectors? Hint: there should be no lattice points inside, or on the faces (lll)fhlhd(lllid)fd(parallolegrams) of, the polyhedron (parallelepiped) formed by these three vectors. -

Crystallography Ll Lattice N-Dimensional, Infinite, Periodic Array of Points, Each of Which Has Identical Surroundings

crystallography ll Lattice n-dimensional, infinite, periodic array of points, each of which has identical surroundings. use this as test for lattice points A2 ("bcc") structure lattice points Lattice n-dimensional, infinite, periodic array of points, each of which has identical surroundings. use this as test for lattice points CsCl structure lattice points Choosing unit cells in a lattice Want very small unit cell - least complicated, fewer atoms Prefer cell with 90° or 120°angles - visualization & geometrical calculations easier Choose cell which reflects symmetry of lattice & crystal structure Choosing unit cells in a lattice Sometimes, a good unit cell has more than one lattice point 2-D example: Primitive cell (one lattice pt./cell) has End-centered cell (two strange angle lattice pts./cell) has 90° angle Choosing unit cells in a lattice Sometimes, a good unit cell has more than one lattice point 3-D example: body-centered cubic (bcc, or I cubic) (two lattice pts./cell) The primitive unit cell is not a cube 14 Bravais lattices Allowed centering types: P I F C primitive body-centered face-centered C end-centered Primitive R - rhombohedral rhombohedral cell (trigonal) centering of trigonal cell 14 Bravais lattices Combine P, I, F, C (A, B), R centering with 7 crystal systems Some combinations don't work, some don't give new lattices - C tetragonal C-centering destroys cubic = P tetragonal symmetry 14 Bravais lattices Only 14 possible (Bravais, 1848) System Allowed centering Triclinic P (primitive) Monoclinic P, I (innerzentiert) Orthorhombic P, I, F (flächenzentiert), A (end centered) Tetragonal P, I Cubic P, I, F Hexagonal P Trigonal P, R (rhombohedral centered) Choosing unit cells in a lattice Unit cell shape must be: 2-D - parallelogram (4 sides) 3-D - parallelepiped (6 faces) Not a unit cell: Choosing unit cells in a lattice Unit cell shape must be: 2-D - parallelogram (4 sides) 3-D - parallelepiped (6 faces) Not a unit cell: correct cell Stereographic projections Show or represent 3-D object in 2-D Procedure: 1. -

Cross Product Review

12.4 Cross Product Review: The dot product of uuuu123, , and v vvv 123, , is u v uvuvuv 112233 uv u u u u v u v cos or cos uv u and v are orthogonal if and only if u v 0 u uv uv compvu projvuv v v vv projvu cross product u v uv23 uv 32 i uv 13 uv 31 j uv 12 uv 21 k u v is orthogonal to both u and v. u v u v sin Geometric description of the cross product of the vectors u and v The cross product of two vectors is a vector! • u x v is perpendicular to u and v • The length of u x v is u v u v sin • The direction is given by the right hand side rule Right hand rule Place your 4 fingers in the direction of the first vector, curl them in the direction of the second vector, Your thumb will point in the direction of the cross product Algebraic description of the cross product of the vectors u and v The cross product of uu1, u 2 , u 3 and v v 1, v 2 , v 3 is uv uv23 uvuv 3231,, uvuv 1312 uv 21 check (u v ) u 0 and ( u v ) v 0 (u v ) u uv23 uvuv 3231 , uvuv 1312 , uv 21 uuu 123 , , uvu231 uvu 321 uvu 312 uvu 132 uvu 123 uvu 213 0 similary: (u v ) v 0 length u v u v sin is a little messier : 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2uv 2 2 2 uvuv sin22 uv 1 cos uv 1 uvuv 22 uv now need to show that u v2 u 2 v 2 u v2 (try it..) An easier way to remember the formula for the cross products is in terms of determinants: ab 12 2x2 determinant: ad bc 4 6 2 cd 34 3x3 determinants: An example Copy 1st 2 columns 1 6 2 sum of sum of 1 6 2 1 6 forward backward 3 1 3 3 1 3 3 1 diagonal diagonal 4 5 2 4 5 2 4 5 products products determinant = 2 72 30 8 15 36 40 59 19 recall: uv uv23 uvuv 3231, uvuv 1312 , uv 21 i j k i j k i j u1 u 2 u 3 u 1 u 2 now we claim that uvu1 u 2 u 3 v1 v 2 v 3 v 1 v 2 v1 v 2 v 3 iuv23 j uv 31 k uv 12 k uv 21 i uv 32 j uv 13 u v uv23 uv 32 i uv 13 uv 31 j uv 12 uv 21 k uv uv23 uvuv 3231,, uvuv 1312 uv 21 Example: Let u1, 2,1 and v 3,1, 2 Find u v. -

Symmetry and Groups, and Crystal Structures

CHAPTER 3: SYMMETRY AND GROUPS, AND CRYSTAL STRUCTURES Sarah Lambart RECAP CHAP. 2 2 different types of close packing: hcp: tetrahedral interstice (ABABA) ccp: octahedral interstice (ABCABC) Definitions: The coordination number or CN is the number of closest neighbors of opposite charge around an ion. It can range from 2 to 12 in ionic structures. These structures are called coordination polyhedron. RECAP CHAP. 2 Rx/Rz C.N. Type Hexagonal or An ideal close-packing of sphere 1.0 12 Cubic for a given CN, can only be Closest Packing achieved for a specific ratio of 1.0 - 0.732 8 Cubic ionic radii between the anions and 0.732 - 0.414 6 Octahedral Tetrahedral (ex.: the cations. 0.414 - 0.225 4 4- SiO4 ) 0.225 - 0.155 3 Triangular <0.155 2 Linear RECAP CHAP. 2 Pauling’s rule: #1: the coodination polyhedron is defined by the ratio Rcation/Ranion #2: The Electrostatic Valency (e.v.) Principle: ev = Z/CN #3: Shared edges and faces of coordination polyhedra decreases the stability of the crystal. #4: In crystal with different cations, those of high valency and small CN tend not to share polyhedral elements #5: The principle of parsimony: The number of different sites in a crystal tends to be small. CONTENT CHAP. 3 (2-3 LECTURES) Definitions: unit cell and lattice 7 Crystal systems 14 Bravais lattices Element of symmetry CRYSTAL LATTICE IN TWO DIMENSIONS A crystal consists of atoms, molecules, or ions in a pattern that repeats in three dimensions. The geometry of the repeating pattern of a crystal can be described in terms of a crystal lattice, constructed by connecting equivalent points throughout the crystal. -

PHZ6426 Crystal Structure

SYMMETRY Finite geometric objects (“molecules) are symmetric with respect to a) rotations b) reflections (symmetry planes, symmetry points) c) combinatons of translations and rotations (screw axes) 2π If an object is symmetric with respect to rotation by angle φ = , it is said to have has an “n-fold rotational axis” n n=1 is a trivial case: every object is symmetric about a full revolution. Non-trivial axes have n>1. 1 Symmetries of an equilateral triangle 2 2 2 180-rotations (flips) 3’ 1’ about 22’ 3 1 3 1 2’ about 33’ about 11’ 1 3 1 2 2 3 3 2 2π 1 120 degree= rotations 3 3 2 1 3 3 3 4 2 2 1 1 An equilateral triangle is not symmetric with respect to inversion about its center. But a square is. 5 Gliding (screw) axis Rotate by 180 degrees about the axis Slide by a half-period 6 2-fold rotations can be viewed as reflections in a plane which contains a 2-fold rotation axis 7 Crystal Structure Crystal structure can be obtained by attaching atoms or groups of atoms --basis-- to lattice sites. Crystal Structure = Crystal Lattice + Basis Crystal Structure 88 Partially from Prof. C. W. Myles (Texas Tech) course presentation Building blocks of lattices are geometric figures with certain symmetries: rotational, reflectional, etc. Lattice must obey all these symmetries but, in addition, it also must obey TRANSLATIONAL symmetry Which geometric figures can be used to built a lattice? 9 10 Crystallographic Restriction Theorem: Crystal lattices have only 2-,3, 4-, and 6-fold rotational symmetries 11 B’ ma A’ n-fold axis φ-π/2 φ=2π/n a A B 1.