P:\CASES\L-3 C. Eotech Inc. (Pre-Award Bid Protest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XPS2™ HWS® (HOLOGRAPHIC WEAPON SIGHT) See Inside Cover for Distribution Statement

OPERATOR’S MANUAL FOR XPS2™ HWS® (HOLOGRAPHIC WEAPON SIGHT) See inside cover for distribution statement. XP1956 EOTech Technical Manual ver. B MARCH 2018 An L-3 Company DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT: Distribution is authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors. This publication is required for administration and operational purposes. Additional copies of this document can be found on the manufacturer’s website. Written requests must be referred to: L3® EOTECH® Service Dept. Attn: TM Request 1201 E. Ellsworth Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48108 (734)741-8868 x2176 [email protected] • This commodity is controlled under the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), ECCN 0A987, and may not be exported to a Foreign Person, either U.S. or abroad, without a license or exception from the U.S. Department of Commerce. WARNING WEAPON SAFETY: Prior to mounting the HWS on your weapon, be sure the weapon is cleared. If you are not sure how to clear your weapon, please see the accompanying operator’s manual for the weapon platform you are mounting the sight on. LASER SAFETY: The HWS is a Class II laser product. The Class II level illuminating beam, however, is completely blocked by the housing. The only laser light accessible to the eye is the image beam and is at a power level within the limit of a Class IIa laser product. The illuminating beam can become accessible to the eye if the housing is broken. Turn the sight off immediately and return the broken unit to the factory for repair. FCC COMPLIANCE: The HWS complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. -

Non-Magnifying Patrol Rifle Sights Summary

August 2013 System Assessment and Validation for Emergency Responders (SAVER) Summary Non-Magnifying Patrol Rifle Sights (AEL reference number 03OE-02-BNOC) Non-magnifying sights aid in aiming patrol rifles and allow law enforcement officers to keep both eyes open, which provides a full field of view, enhances situational awareness, and helps users maintain depth perception. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) established the System Assessment To provide responders with information on currently available non-magnifying and Validation for Emergency Responders patrol rifle sights, the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Center (SAVER) Program to assist emergency (SPAWARSYSCEN) Atlantic conducted a comparative assessment of these responders making procurement decisions. sights for the System Assessment and Validation for Emergency Responders Located within the Science and Technology (SAVER) Program in July 2012. Detailed findings are provided in the Directorate (S&T) of DHS, the SAVER Non-Magnifying Patrol Rifle Sights Assessment Report, which is available by Program conducts objective assessments request at https://www.rkb.us/saver. and validations on commercial equipment and systems, and provides those results along with other relevant equipment Assessment Methodology information to the emergency responder Prior to the assessment, eight law enforcement personnel were chosen from community in an operationally useful form. SAVER provides information on equipment various jurisdictions to participate in a focus group. All participants had that falls within the categories listed in the experience using non-magnifying patrol rifle sights. The focus group DHS Authorized Equipment List (AEL). identified evaluation criteria and recommended product selection criteria and The SAVER Program is supported by a possible scenarios for assessment. -

2020 Product Catalog Tm

TM 2020 PRODUCT CATALOG TM SENTRY Products Group. We Live to Protect! 2 We are proud to introduce our 2020 product assortment featuring new products, new categories and further expansion of our tactical nylon line. While the nylon line had seen steady growth, a visit from a key customer in the summer of 2019 changed the pace of our development creating a combination of lightweight and configurable components with the flexibility to meet changing mission demands. For the latest project check out the Gunnar Series Plate carrier featured on page 10. Along with our nylon line developments the hybrid Hexmag magazine which combined the best attributes of metal and polymer technologies was launched to support the Glock 17. Additional platforms are in the works as we continue to expand the Hexmag line up. Whether you protect your home, family, or country, our commitment to you is simple – we will continue to produce the best, most innovative product on the market to enhance your experience. We are so confident that we back each product with a hassle- free Lifetime Warranty, protecting your investment. From the team at SENTRY, thank you for your support and confidence. TABLE OF CONTENTS MAGAZINES . .4-7 ON GUN ACCESSORIES . 8-9 PLATE CARRIER AND ACCESSORIES . 10-13 BELTS AND POUCHES . 14-21 SLINGS. .22-23 OPTIC COVERS. .24-29 FIREARM COVERS . .30-33 CLEANING AND LUBRICATION. .34-39 BAGS. .40-41 OEM PROGRAMS. .42-43 3 When every round counts™ 4 ™ POLYHEX2 The proprietary advanced composite that all Hexmag magazines are made from delivers superior strength and reliable performance across the modern sporting rifle and pistol spectrum. -

Optics & Acc 270-277

AIMPOINT Item AIMPOINT OPTICS & ACCESSORIES INDEX PATROL RIFLE OPTIC Micro T-2 RED DOT SIGHT Red Dot Sights ..................270-275 Scope Accessories ...............275-276 Rugged, Reliable & Versatile - Enhanced, Night Vision Compatible Always Ready Edition Of This Popular Red Dot The Micro T-2 is a redesigned, Parallax-free, non-magnifying red upgraded evolution of the original BURRIS dot sight is ready at all times, with no T-1 that adds compatibility with all switches or levers to fumble with. Sim- generations of night vision devices RED DOT REFLEX SIGHTS after 8 hours help keep you from running out of power at the wrong ply install the supplied battery, turn the (NVD). The T-2 retains the original’s time. Windage and elevation adjustments can be made quickly PRO on, and forget about it – for up ruggedness and reliability, while add- Fast, Precise Heads-Up Sighting; with a coin - no special tool needed - with a 3° (190" at 100 yards) to 3 years! 2 MOA center-dot, with 6 ing a unique coating on the front lens Ultra-Robust Design Handles adjustment range. Available with 3 or 8 MOA dot, with or without daylight and 4 night vision brightness that reflects the 2 MOA dot’s red light Magnum-Power Recoil quick-attach/detach Picatinny mount. settings, enables accurate target en- at nearly 100% efficiency to give the highest possible dot clarity SPECS: Aluminum, stainless steel, and bronze, matte black finish. 1.9" gagement under a broad variety of conditions. Includes a detach- and brightness. This provides a remarkably clear image when used OPTICS & ACCESSORIES FASTFIRE II - Provides fast, both-eyes- (48.2mm) long x 1" (25.4mm) wide x 1" high. -

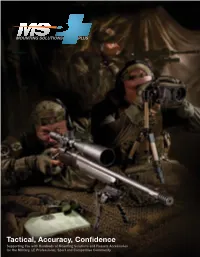

Tactical, Accuracy, Confidence

Tactical • Accuracy • Confidence Tactical, Accuracy, Confidence Supporting You with Hundreds of Mounting Solutions and Firearm Accessories 1-800-428-9394for the Military, LE Professional, Sport and Competitive Community 1 New for 2013 Featured Sections 4 Scope Rings & Mounts Weaver, A.R.M.S., PRI 9 AR Rail & Accessories A.R.M.S., Samson & Magpul 21 Mini 14 Accessories Tapco, ATI AP Custom Carbon-fiber Free-Float Handguards The AP Custom handguard is a carbon-fiber free float 23 AK Accessories tube with all of the mounting hardware included. Our Tapco, Samson & ATI carbon-fiber tubes attach to the gun using our proprietary trunnion and a standard, mil-spec barrel nut. No special tools or epoxies are need to secure your handguard. The 25 H&K Accessories carbon-fiber tubes are slotted at 2,3, 6, 9, and 10 o’clock. A.R.M.S., Samson, MFI The slots double as heat vents and purchase points for our 2 and 4 in. Picatinny rail sections. Page 13 26 M14/M1A Accessories Trijicon SRS - Sealed Reflex Sight 1.75 MOA A.R.M.S. & Sadlak Ind. The Trijicon SRS (Sealed Reflex Sight) represents the highest level of performance from a sealed reflex-style sight. Because of its innovative design, the SRS takes up less rail space while maintaining the durability expected from Trijicon. The shorter 26 FAL Accessories housing eliminates the tube-effect typical of other sealed reflex sights. Featuring a Magpul, A.R.M.S., & Tapco large 28mm aperture, the Trijicon SRS provides a massive field of view for quicker target engagements. -

Tavor Meprolight M21 Owners Manual

1 / 2 Tavor Meprolight M21 Owners Manual ... are provided for the Meprolight MP 21, ITL MARS with integrated laser and IR pointer, Trijicon ACOG, EOTech holographic sight and other optical sights. The IWI Tavor TAR-21 is an Israeli bullpup assault rifle chambered in 5.56×45mm NATO caliber ... Tavor CTAR-21 bullpup assault rifles saw combat service in Operation Cast .... It comes with a Meprolight® MEPRO 21 Day/Night Illuminated reflex sight mounted directly to the barrel, just as it is issued to the IDF (Israel Defense Forces).. Read the manual, took out the accessories and memorized nomenclature of parts.. ... But back to the topic at hand the Meprolight M21 sight is a win on this rifle. ... Canadian Tavor owners reported that P-mags or any other plastic mag will have .... The Tavor incorporates flip up backup iron sights if the Mepro-21 goes dark. ... kit provided with instructions from the best owner's manual I have ever seen.. Dec 4, 2020 — The birth of the Tavor X95 was first issued to Israeli Defense Force IDF troops in ... one of the most compatible, user-friendly magazines on the market. ... imported Israeli-made TCs, equipped with Mepro M5 or M21 reflex ... Emist epix 360 · Tp link powerline utility · Maglite led bulb replacement instructions .... The manual includes detailed zero instructions, a zero target diagram, and a ... Mepro TRU-DOT RDS and Mepro M21 forward-mounted on Sa vz.58 Rifles.. TAVOR TS12 SHOTGUN OPERATOR MANUAL Read the instructions and ... Mako Group Mepro 21 / Meprolight M21 Illuminator REM 21 (Reticle Enhancement .... No batteries needed ever. -

EXPS2™ HWS® (HOLOGRAPHIC WEAPON SIGHT) See Inside Cover for Distribution Statement

OPERATOR’S MANUAL FOR EXPS2™ HWS® (HOLOGRAPHIC WEAPON SIGHT) See inside cover for distribution statement. XE1973 EOTECH Technical Manual ver. B MARCH 2018 An L-3 Company DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT: Distribution is authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors. This publication is required for administration and operational purposes. Additional copies of this document can be found on the manufacturer’s website. Written requests must be referred to: L3® EOTECH® Service Dept. Attn: TM Request 1201 E. Ellsworth Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48108 (734)741-8868 x2176 [email protected] • This commodity is controlled under the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), ECCN 0A987, and may not be exported to a Foreign Person, either U.S. or abroad, without a license or exception from the U.S. Department of Commerce. WARNING WEAPON SAFETY: Prior to mounting the HWS on your weapon, be sure the weapon is cleared. If you are not sure how to clear your weapon, please see the accompanying operator’s manual for the weapon platform you are mounting the sight on. LASER SAFETY: The HWS is a Class II laser product. The Class II level illuminating beam, however, is completely blocked by the housing. The only laser light accessible to the eye is the image beam and is at a power level within the limit of a Class IIa laser product. The illuminating beam can become accessible to the eye if the housing is broken. Turn the sight off immediately and return the broken unit to the factory for repair. FCC COMPLIANCE: The HWS complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. -

EXPS3™ HWS® (HOLOGRAPHIC WEAPON SIGHT) See Inside Cover for Distribution Statement

OPERATOR’S MANUAL FOR EXPS3™ HWS® (HOLOGRAPHIC WEAPON SIGHT) See inside cover for distribution statement. XE1974 EOTECH Technical Manual ver. B MARCH 2018 An L-3 Company DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT: Distribution is authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors. This publication is required for administration and operational purposes. Additional copies of this document can be found on the manufacturer’s website. Written requests must be referred to: L3® EOTECH® Service Dept. Attn: TM Request 1201 E. Ellsworth Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48108 (734)741-8868 x2176 [email protected] • This commodity is controlled under the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), ECCN 0A987, and may not be exported to a Foreign Person, either U.S. or abroad, without a license or exception from the U.S. Department of Commerce. WARNING WEAPON SAFETY: Prior to mounting the HWS on your weapon, be sure the weapon is cleared. If you are not sure how to clear your weapon, please see the accompanying operator’s manual for the weapon platform you are mounting the sight on. LASER SAFETY: The HWS is a Class II laser product. The Class II level illuminating beam, however, is completely blocked by the housing. The only laser light accessible to the eye is the image beam and is at a power level within the limit of a Class IIa laser product. The illuminating beam can become accessible to the eye if the housing is broken. Turn the sight off immediately and return the broken unit to the factory for repair. FCC COMPLIANCE: The HWS complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. -

Warning Caution

OPERATOR’S MANUAL FOR HWS 557.AR223 REFLEX SIGHT, HOLOGRAPHIC, NV COMPATIBLE, AA, L-3 EOTECH ORDER CODE: 557.AR223 See inside cover for distribution statement. L-3 Eotech Technical Manual ver. 1.0 APRIL 2007 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT: Distribution is authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors. This publication is required for administration and operational purposes. Additional copies of this document can be found on the manufacturer’s website. Written requests must be referred to: L-3 EOTech Service Dept. Attn: TM Request 1201 E.Ellsworth Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48108 (734)741-8868 x3688 [email protected] DESTRUCTION NOTICE: Destroy the sight’s operability by removing the battery cap, batteries, and then crushing the battery cap. Destroy this document by any method that will prevent disclosure of contents or reconstruction of the document. WARNING WEAPON SAFETY: Prior to mounting the Holographic Weapon Sight (HWS) on a weapon, be sure the weapon is cleared. If you are not sure how to clear the weapon, please see the operator’s manual for the weapon platform you are mounting the HWS on. LASER SAFETY: The HWS is a Class II laser product. The Class II level illuminating beam, however, is completely blocked by the housing. The only laser light accessible to the eye is the image beam and produces a power level that is within the limit of a Class IIa laser product. The illuminating beam can be viewed directly by eye if the housing is broken. Turn the sight off immediately and return the broken unit to the factory for repair. -

Bcm Mid-16 Mod 2 Carbine Package!

HUGE PRIZE BCM MID-16 MOD 2 CARBINE PACKAGE! SURVIVAL WEAPONS AND TACTICS WILSON COMBAT AR9G LIGHTWEIGHT, MANEUVERABLE, ERGONOMIC THERMAL IMAGING FOR SMARTPHONES ‘N’ OT SA O V H E S • • $ S E 300 SHOOTOUT H V O A O S T ’ ‘ N TESTING BARGAIN BLASTERS MAY 2017 LOOKING FOR A FEW TACTICAL GOOD MARKSMEN ENERGETIC ULFBERHT PRECISION SEMIAUTO RIFLE ENTRY SYSTEMS WHITE LIGHT PLACEMENT ■ HISTORY OF SOPMOD desert warrior® 39 ounces | 5 inch barrel available in .45 ACP trust is earned america’s best rely on kimber—so should you. (888) 243-4522 made in america what all guns should be™ kimberamerica.com ©2017, kimber mfg., inc. all rights reserved. information and specifications are for reference only and subject to change without notice. KIM_2016_Warrior_SWAT.indd 1 12/20/16 3:28 PM BC_Swat_GF.qxp 2/15/17 8:08 AM Page 1 desert warrior® 39 ounces | 5 inch barrel available in .45 ACP trust is earned america’s best rely on kimber—so should you. Hartland, WI U.S.A. / Fax: 262-367-0989 (888) 243-4522 Toll Free: 1-877-BRAVO CO / 1-877-272-8626 made in america what all guns should be™ kimberamerica.com ©2017, kimber mfg., inc. all rights reserved. information and specifications are for reference only and subject to change without notice. KIM_2016_Warrior_SWAT.indd 1 12/20/16 3:28 PM LINEUP MAY 2017 SURVIVAL WEAPONS AND TACTICS LIGHTWEIGHT, MANEUVERABLE, ERGONOMIC 9MM CARBINE Wilson Combat AR9G Carbines that use pistol magazines are a growing 52 segment of the market. COVER Wilson’s rendition is among BY ANDY MASSIMILIAN STORY the highest quality available. -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D European & Security ES & Defence 8/2017 International Security and Defence Journal COUNTRY FOCUS: HUNGARY ISSN 1617-7983 • www.euro-sd.com • December 2017 Night Vision EU in Action Conventional Submarines European military and civilian missions and Strong demand is being spurred on by new security operations challenges Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Editorial Much Ado About Little athos, kitsch and euphoric resolutions mood. Citizens expect politicians to invest Phave always been part of the style rep- more in internal and external security and ertoire of European summits. If they were to tackle cross-border problems in cross- formerly reserved for the real landmarks border cooperation. Who, if not the EU, of European integration, their use today should be able to provide a suitable frame- is inflationary. Since the outbreak of the work for this? financial crisis more than a decade ago, the And yet, prudence is required. Actionism European Union has been working on a is not a concept yet. On the contrary. To steadily growing number of problems that it advance this or that project in an uncon- is failing to master. Wherever the attempted trolled fashion on the basis of current op- solutions lack the power of persuasion, at portunities and interests can very quickly least their staging and full-bodied rhetoric lead to a veritable waste of resources. are supposed to convey confidence. If you Moreover, PESCO is not a new brilliant summarise all the important courses that idea, but an instrument provided for by have recently been set in this way, the ques- the Treaty of Lisbon a decade ago. -

ADS Weapons & Optics Equipment & Capabilities Catalog

VOL. 2.0 CLEANING & MAINTENANCE COMPONENTS & SYSTEMS KITTING STORAGE WEAPONS & OPTICS EQUIPMENT & CAPABILITIES TRAINING VISUAL AUGMENTATION WEAPONS & ACCESSORIES OUR PURPOSE. YOUR MISSION. WEAPONS & OPTICS EQUIPMENT & SERVICES PROCUREMENT & CONTRACTS SUPPORT & LOGISTICS FEATURED ARTICLES TIME FOR A REDUCED SWAP-C & INCREASING USSOCOM 10 LETHALITY CHECK 12 INCREASED LETHALITY 26 OPERATOR READINESS Crew-Served Target For Currently Fielded With Product Engagement Weapon Systems Development & Custom Kitted Solutions Trijicon .......................................64 MOUNTS & RAILS TRAINING SYSTEMS CONTENTS Vectronix ....................................68 Adams Industries .......................14 Laser Shot ..................................42 Cadex Defense ...........................20 About ADS ..................................... 3 ILLUMINATORS WEAPONS Daniel Defense ...........................28 Equipment & Services ................... 4 BE Meyers ..................................18 Global Defense Initiatives ...........34 Daniel Defense ...........................28 L-3 Warrior Systems Insight .......38 Procurement & Contracts ............. 7 Wilcox Industries ........................70 Remington .................................54 Trijicon .......................................64 SIG SAUER .................................58 Support & Logistics ...................... 8 NIGHT VISION Troy Industries ...........................66 KITS Adams Industries .......................14 WEAPONS COMPONENTS Cadex .........................................20