Understanding the Luminosity and Surface Temperature of Stars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:2007.13451V2 [Gr-Qc] 24 Nov 2020 on GR and Its Modifications [31–33], but Also Delivers Model Particles As Well As Dark Matter Candidates [56– Drawbacks](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4392/arxiv-2007-13451v2-gr-qc-24-nov-2020-on-gr-and-its-modi-cations-31-33-but-also-delivers-model-particles-as-well-as-dark-matter-candidates-56-drawbacks-14392.webp)

Arxiv:2007.13451V2 [Gr-Qc] 24 Nov 2020 on GR and Its Modifications [31–33], but Also Delivers Model Particles As Well As Dark Matter Candidates [56– Drawbacks

Early evolutionary tracks of low-mass stellar objects in modified gravity Aneta Wojnar1, ∗ 1Laboratory of Theoretical Physics, Institute of Physics, University of Tartu, W. Ostwaldi 1, 50411 Tartu, Estonia Using a simple model of low-mass stellar objects we have shown modified gravity impact on their early evolution, such as Hayashi tracks, radiative core development, effective temperature, masses, and luminosities. We have also suggested that the upper mass' limit of fully convective stars on the Main Sequence might be different than commonly adopted. I. INTRODUCTION is, in the so-called mass gap [38]), which merged with a black hole of 23M , provided even more questions for Working on modified gravity does not make one to for- theoretical physics of compact objects. get the elegance and success of Einstein's theory of grav- However, it turns out that there is a class of stellar ity, being already confirmed by many observations [1]; objects, with the internal structure much better under- even more, General Relativity (GR) still delights when stood than that of neutron stars, which might be used to one of its mysterious predictions, such as the existence of constrain theories of gravity. It is a family of low-mass black holes, is directly affirmed by the finding of gravi- stars (LMS) [39{41] which includes such ordinary objects tational waves as a result of black holes' binary mergers as M dwarfs (also called red dwarfs), which are cool Main [2] as well as soon after the imaging of the shadow of the Sequence stars with masses in the range [0:09 − 0:6]M , supermassive black hole of M87 [3] (see [4] for a review). -

Revisiting the Pre-Main-Sequence Evolution of Stars I. Importance of Accretion Efficiency and Deuterium Abundance ?

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. Kunitomo_etal c ESO 2018 March 22, 2018 Revisiting the pre-main-sequence evolution of stars I. Importance of accretion efficiency and deuterium abundance ? Masanobu Kunitomo1, Tristan Guillot2, Taku Takeuchi,3,?? and Shigeru Ida4 1 Department of Physics, Nagoya University, Furo-cho, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya, Aichi 464-8602, Japan e-mail: [email protected] 2 Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, CNRS UMR 7293, 06304 Nice CEDEX 04, France 3 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8551, Japan 4 Earth-Life Science Institute, Tokyo Institute of Technology, 2-12-1 Ookayama, Meguro-ku, Tokyo 152-8551, Japan Received 5 February 2016 / Accepted 6 December 2016 ABSTRACT Context. Protostars grow from the first formation of a small seed and subsequent accretion of material. Recent theoretical work has shown that the pre-main-sequence (PMS) evolution of stars is much more complex than previously envisioned. Instead of the traditional steady, one-dimensional solution, accretion may be episodic and not necessarily symmetrical, thereby affecting the energy deposited inside the star and its interior structure. Aims. Given this new framework, we want to understand what controls the evolution of accreting stars. Methods. We use the MESA stellar evolution code with various sets of conditions. In particular, we account for the (unknown) efficiency of accretion in burying gravitational energy into the protostar through a parameter, ξ, and we vary the amount of deuterium present. Results. We confirm the findings of previous works that, in terms of evolutionary tracks on the Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) diagram, the evolution changes significantly with the amount of energy that is lost during accretion. -

Single Star Implementation Notes

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000{000 (0000) Printed 8 November 2017 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) Single Star Implementation Notes PFH 8 November 2017 1 METHODS 1=2 − 1 times the cloud diameter Lcloud) are driven as an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process in Fourier space, with the com- Our simulations use GIZMO (?),1, and include full self- pressive part of the modes projected out via Helmholtz de- gravity, adaptive resolution, ideal and non-ideal magneto- composition so that we can specify the ratio of compress- hydrodynamics (MHD), detailed cooling and heating ible and incompressible/solenoidal modes. Unless otherwise physics, protostar formation, accretion, and feedback in the specified we adopt pure solenoidal driving, appropriate for form of protostellar jets and radiative heating, and main- e.g. galactic shear (so that we do not artificially \force" com- sequence stellar feedback in the form of photo-ionization pression/collapse), but we vary this. The specific implemen- and photo-electric heating, radiation pressure, stellar winds, tation here has been verified in ????. and supernovae. A subset of our runs include explicit treat- The driving specifies the large-scale steady-state (one- ment of the dust particle and cosmic ray dynamics as well dimensional) turbulent velocity σ ≡ hv2 i1=2 and as radiation-hydrodynamics; otherwise these are included in 1D turb; 1D Mach number M ≡ h(v =c )2i1=2, where v is simplified form. turb; 1D s turb; 1D an (arbitrary) projection (in detail we average over all 1.1 Gravity random projections). Unless otherwise specified, we initial- ize our clouds on the linewidth-size relation from ?, with All our simulations include full self-gravity for gas, stars, −1 1=2 σ1D ≈ 0:7 km s (Lcloud=pc) and dust. -

Useful Constants

Appendix A Useful Constants A.1 Physical Constants Table A.1 Physical constants in SI units Symbol Constant Value c Speed of light 2.997925 × 108 m/s −19 e Elementary charge 1.602191 × 10 C −12 2 2 3 ε0 Permittivity 8.854 × 10 C s / kgm −7 2 μ0 Permeability 4π × 10 kgm/C −27 mH Atomic mass unit 1.660531 × 10 kg −31 me Electron mass 9.109558 × 10 kg −27 mp Proton mass 1.672614 × 10 kg −27 mn Neutron mass 1.674920 × 10 kg h Planck constant 6.626196 × 10−34 Js h¯ Planck constant 1.054591 × 10−34 Js R Gas constant 8.314510 × 103 J/(kgK) −23 k Boltzmann constant 1.380622 × 10 J/K −8 2 4 σ Stefan–Boltzmann constant 5.66961 × 10 W/ m K G Gravitational constant 6.6732 × 10−11 m3/ kgs2 M. Benacquista, An Introduction to the Evolution of Single and Binary Stars, 223 Undergraduate Lecture Notes in Physics, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-9991-7, © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 224 A Useful Constants Table A.2 Useful combinations and alternate units Symbol Constant Value 2 mHc Atomic mass unit 931.50MeV 2 mec Electron rest mass energy 511.00keV 2 mpc Proton rest mass energy 938.28MeV 2 mnc Neutron rest mass energy 939.57MeV h Planck constant 4.136 × 10−15 eVs h¯ Planck constant 6.582 × 10−16 eVs k Boltzmann constant 8.617 × 10−5 eV/K hc 1,240eVnm hc¯ 197.3eVnm 2 e /(4πε0) 1.440eVnm A.2 Astronomical Constants Table A.3 Astronomical units Symbol Constant Value AU Astronomical unit 1.4959787066 × 1011 m ly Light year 9.460730472 × 1015 m pc Parsec 2.0624806 × 105 AU 3.2615638ly 3.0856776 × 1016 m d Sidereal day 23h 56m 04.0905309s 8.61640905309 -

Stellar Evolution

Stellar Astrophysics: Stellar Evolution 1 Stellar Evolution Update date: December 14, 2010 With the understanding of the basic physical processes in stars, we now proceed to study their evolution. In particular, we will focus on discussing how such processes are related to key characteristics seen in the HRD. 1 Star Formation From the virial theorem, 2E = −Ω, we have Z M 3kT M GMr = dMr (1) µmA 0 r for the hydrostatic equilibrium of a gas sphere with a total mass M. Assuming that the density is constant, the right side of the equation is 3=5(GM 2=R). If the left side is smaller than the right side, the cloud would collapse. For the given chemical composition, ρ and T , this criterion gives the minimum mass (called Jeans mass) of the cloud to undergo a gravitational collapse: 3 1=2 5kT 3=2 M > MJ ≡ : (2) 4πρ GµmA 5 For typical temperatures and densities of large molecular clouds, MJ ∼ 10 M with −1=2 a collapse time scale of tff ≈ (Gρ) . Such mass clouds may be formed in spiral density waves and other density perturbations (e.g., caused by the expansion of a supernova remnant or superbubble). What exactly happens during the collapse depends very much on the temperature evolution of the cloud. Initially, the cooling processes (due to molecular and dust radiation) are very efficient. If the cooling time scale tcool is much shorter than tff , −1=2 the collapse is approximately isothermal. As MJ / ρ decreases, inhomogeneities with mass larger than the actual MJ will collapse by themselves with their local tff , different from the initial tff of the whole cloud. -

Phys 321: Lecture 7 Stellar Evolu�On

Phys 321: Lecture 7 Stellar Evolu>on Prof. Bin Chen, Tiernan Hall 101, [email protected] Stellar Evoluon • Formaon of protostars (covered in Phys 320; briefly reviewed here) • Pre-main-sequence evolu>on (this lecture) • Evolu>on on the main sequence (this lecture) • Post-main-sequence evolu>on (this lecture) • Stellar death (next lecture) The Interstellar Medium and Star Formation the cloud’s internal kinetic energy, given by The Interstellar Medium and Star Formation the cloud’s internal kinetic energy, given by 3 K NkT, 3 = 2 The Interstellar MediumK andNkT, Star Formation = 2 where N is the total number2 ofTHE particles. FORMATIONwhere ButNNisis the just total OF number PROTOSTARS of particles. But N is just M Mc N c , Our understandingN , of stellar evolution has= µm developedH significantly since the 1960s, reaching = µmH the pointwhere whereµ is the much mean of molecular the life weight. history Now, of by a the star virial is theorem, well determined. the condition for This collapse success has been where µ is the mean molecular weight.due to advances Now,(2K< byU the in) becomes observational virial theorem, techniques, the condition improvements for collapse in our knowledge of the physical | | (2K< U ) becomes processes important in stars, and increases in computational2 power. In the remainder of this | | 3MckT 3 GMc chapter, we will present an overview of< the lives. of stars, leaving de(12)tailed discussions 2 µmH 5 Rc of s3oMmeckTspecia3l pGMhasces of evolution until later, specifically stellar pulsation, supernovae, The radius< may be replaced. by using the initial mass density(12) of the cloud, ρ , assumed here µmH 5 Rc 0 and comtop beac constantt objec throughoutts (stellar theco cloud,rpses). -

Astronomy General Information

ASTRONOMY GENERAL INFORMATION HERTZSPRUNG-RUSSELL (H-R) DIAGRAMS -A scatter graph of stars showing the relationship between the stars’ absolute magnitude or luminosities versus their spectral types or classifications and effective temperatures. -Can be used to measure distance to a star cluster by comparing apparent magnitude of stars with abs. magnitudes of stars with known distances (AKA model stars). Observed group plotted and then overlapped via shift in vertical direction. Difference in magnitude bridge equals distance modulus. Known as Spectroscopic Parallax. SPECTRA HARVARD SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION (1-D) -Groups stars by surface atmospheric temp. Used in H-R diag. vs. Luminosity/Abs. Mag. Class* Color Descr. Actual Color Mass (M☉) Radius(R☉) Lumin.(L☉) O Blue Blue B Blue-white Deep B-W 2.1-16 1.8-6.6 25-30,000 A White Blue-white 1.4-2.1 1.4-1.8 5-25 F Yellow-white White 1.04-1.4 1.15-1.4 1.5-5 G Yellow Yellowish-W 0.8-1.04 0.96-1.15 0.6-1.5 K Orange Pale Y-O 0.45-0.8 0.7-0.96 0.08-0.6 M Red Lt. Orange-Red 0.08-0.45 *Very weak stars of classes L, T, and Y are not included. -Classes are further divided by Arabic numerals (0-9), and then even further by half subtypes. The lower the number, the hotter (e.g. A0 is hotter than an A7 star) YERKES/MK SPECTRAL CLASSIFICATION (2-D!) -Groups stars based on both temperature and luminosity based on spectral lines. -

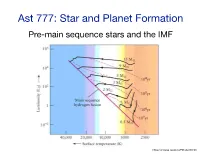

Ast 777: Star and Planet Formation Pre-Main Sequence Stars and the IMF

Ast 777: Star and Planet Formation Pre-main sequence stars and the IMF https://universe-review.ca/F08-star05.htm The main phases of star formation https://www.americanscientist.org/sites/americanscientist.org/files/2005223144527_306.pdf The star has formed* but is not yet on the MS * it has attained its final mass (or ~99% of it) https://www.americanscientist.org/sites/americanscientist.org/files/2005223144527_306.pdf The star is optically visible and is a Class II or III star (or TTS or HAeBe) https://www.americanscientist.org/sites/americanscientist.org/files/2005223144527_306.pdf PMS evolution is described by the equations of stellar evolution But there are differences from MS evolution: ‣ initial conditions are very different from the MS (and have significant uncertainties) ‣ energy is produced by gravitational collapse and deuterium burning (This was mostly figured out 30-50 years ago so the references are old, but important for putting current work in context) But see later… How big is a star when the core stops collapsing? Upper limit can be determined by assuming that all the gravitational energy of the core is used to dissociate and ionized the H2+He gas (i.e., no radiative losses during collapse) Each H2 requires 4.48eV to dissociate —> this produces a short-lived intermediate step along the way to a protostar, called the first hydrostatic core (hinted at, though not definitively confirmed, through FIR/mm observations) How big is a star when the core stops collapsing? Upper limit can be determined by assuming that all the gravitational -

The Influence of Radiative Core Growth on Coronal X-Ray Emission from Pre

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE MNRAS Advance Access published February 2, 2016 provided by St Andrews Research Repository MNRAS 000, 1–22 (2015) Preprint 30 January 2016 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 The influence of radiative core growth on coronal X-ray emission from pre-main sequence stars Scott G. Gregory,1? Fred C. Adams2;3 and Claire L. Davies4;1 1SUPA, School of Physics & Astronomy, University of St Andrews, St Andrews, KY16 9SS, U.K. 2Physics Department, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, U.S.A. 3Astronomy Department, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, U.S.A. 4School of Physics, University of Exeter, Exeter, EX4 4QL, U.K. Downloaded from Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT Pre-main sequence (PMS) stars of mass & 0:35 M transition from hosting fully convective interiors to configurations with a radiative core and outer convective envelope during their http://mnras.oxfordjournals.org/ gravitational contraction. This stellar structure change influences the external magnetic field topology and, as we demonstrate herein, affects the coronal X-ray emission as a stellar analog of the solar tachocline develops. We have combined archival X-ray, spectroscopic, and photo- metric data for ∼1000 PMS stars from five of the best studied star forming regions; the ONC, NGC 2264, IC 348, NGC 2362, and NGC 6530. Using a modern, PMS calibrated, spectral type-to-effective temperature and intrinsic colour scale, we deredden the photometry using colours appropriate for each spectral type, and determine the stellar mass, age, and internal structure consistently for the entire sample. -

Chapter 5 Theory of Stellar Evolution

1 ⋅ Stellar Interiors Copyright (2003) George W. Collins, II 5 Theory of Stellar Evolution . One of the great triumphs of the twentieth century has been the detailed description of the life history of a star. We now understand with some confidence more than 90 percent of that life history. Problems still exist for the very early phases and the terminal phases of a star's life. These phases are very short, and the problems arise as much from the lack of observational data as from the difficulties encountered in the theoretical description. Nevertheless, continual progress is being made, and it would not be surprising if even these remaining problems are solved by the end of the century. 112 5 ⋅ Theory of Stellar Evolution To avoid vagaries and descriptions which may later prove inaccurate, we concentrate on what is known with some certainty. Thus, we assume that stars can contract out of the interstellar medium, and generally we avoid most of the detailed description of the final, fatal collapse of massive stars. In addition, the fascinating field of the evolution of close binary stars, where the evolution of one member of the system influences the evolution of the other through mass exchange, will be left for another time. The evolution of so-called normal stars is our central concern. Although the details of the theory of stellar evolution are complex, it is possible to gain some insight into the results expected of these calculations from some simple considerations. We have developed all the formalisms for calculating steady-state stellar models. However, those models could often be accurately represented by an equilibrium model composed of a polytrope or combinations of polytropes. -

Proto and Pre-Main Sequence Stellar Evolution in a Molecular Cloud Environment

MNRAS 000,1{20 (2017) Preprint 1 February 2018 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Explaining the luminosity spread in young clusters: proto and pre-main sequence stellar evolution in a molecular cloud environment Sigurd S. Jensen? & Troels Haugbølley Centre for Star and Planet Formation, Niels Bohr Institute and Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, Øster Voldgade 5-7, DK-1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark Accepted 2017 October 31. Received October 30; in original form 2017 June 27 ABSTRACT Hertzsprung-Russell diagrams of star forming regions show a large luminosity spread. This is incompatible with well-defined isochrones based on classic non-accreting pro- tostellar evolution models. Protostars do not evolve in isolation of their environment, but grow through accretion of gas. In addition, while an age can be defined for a star forming region, the ages of individual stars in the region will vary. We show how the combined effect of a protostellar age spread, a consequence of sustained star formation in the molecular cloud, and time-varying protostellar accretion for individual proto- stars can explain the observed luminosity spread. We use a global MHD simulation including a sub-scale sink particle model of a star forming region to follow the accre- tion process of each star. The accretion profiles are used to compute stellar evolution models for each star, incorporating a model of how the accretion energy is distributed to the disk, radiated away at the accretion shock, or incorporated into the outer lay- ers of the protostar. Using a modelled cluster age of 5 Myr we naturally reproduce the luminosity spread and find good agreement with observations of the Collinder 69 cluster, and the Orion Nebular Cluster. -

8.901 Lecture Notes Astrophysics I, Spring 2019

8.901 Lecture Notes Astrophysics I, Spring 2019 I.J.M. Crossfield (with S. Hughes and E. Mills)* MIT 6th February, 2019 – 15th May, 2019 Contents 1 Introduction to Astronomy and Astrophysics 6 2 The Two-Body Problem and Kepler’s Laws 10 3 The Two-Body Problem, Continued 14 4 Binary Systems 21 4.1 Empirical Facts about binaries................... 21 4.2 Parameterization of Binary Orbits................. 21 4.3 Binary Observations......................... 22 5 Gravitational Waves 25 5.1 Gravitational Radiation........................ 27 5.2 Practical Effects............................ 28 6 Radiation 30 6.1 Radiation from Space......................... 30 6.2 Conservation of Specific Intensity................. 33 6.3 Blackbody Radiation......................... 36 6.4 Radiation, Luminosity, and Temperature............. 37 7 Radiative Transfer 38 7.1 The Equation of Radiative Transfer................. 38 7.2 Solutions to the Radiative Transfer Equation........... 40 7.3 Kirchhoff’s Laws........................... 41 8 Stellar Classification, Spectra, and Some Thermodynamics 44 8.1 Classification.............................. 44 8.2 Thermodynamic Equilibrium.................... 46 8.3 Local Thermodynamic Equilibrium................ 47 8.4 Stellar Lines and Atomic Populations............... 48 *[email protected] 1 Contents 8.5 The Saha Equation.......................... 48 9 Stellar Atmospheres 54 9.1 The Plane-parallel Approximation................. 54 9.2 Gray Atmosphere........................... 56 9.3 The Eddington Approximation................... 59 9.4 Frequency-Dependent Quantities.................. 61 9.5 Opacities................................ 62 10 Timescales in Stellar Interiors 67 10.1 Photon collisions with matter.................... 67 10.2 Gravity and the free-fall timescale................. 68 10.3 The sound-crossing time....................... 71 10.4 Radiation transport.......................... 72 10.5 Thermal (Kelvin-Helmholtz) timescale............... 72 10.6 Nuclear timescale..........................