A Qualitative Study of Music Consumption in Today's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

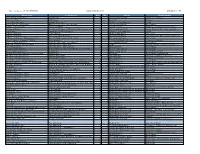

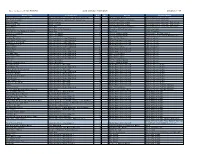

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Punk Preludes

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Summer 8-1996 Punk Preludes Travis Gerarde Buck University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Buck, Travis Gerarde, "Punk Preludes" (1996). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/160 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Punk Preludes Travis Buck Senior Honors Project University of Tennessee, Knoxville Abstract This paper is an analysis of some of the lyrics of two early punk rock bands, The Sex Pistols and The Dead Kennedys. Focus is made on the background of the lyrics and the sub-text as well as text of the lyrics. There is also some analysis of punk's impact on mondern music During the mid to late 1970's a new genre of music crept into the popular culture on both sides of the Atlantic; this genre became known as punk rock. Divorcing themselves from the mainstream of music and estranging nlany on their way, punk musicians challenged both nlusical and cultural conventions. The music, for the most part, was written by the performers and performed without worrying about what other people thought of it. -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Punk Lyrics and Their Cultural and Ideological Background: a Literary Analysis

Punk Lyrics and their Cultural and Ideological Background: A Literary Analysis Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens Universität Graz vorgelegt von Gerfried AMBROSCH am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: A.o. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION – What Is Punk? 5 1. ANARCHY IN THE UK 14 2. AMERICAN HARDCORE 26 2.1. STRAIGHT EDGE 44 2.2. THE NINETEEN-NINETIES AND EARLY TWOTHOUSANDS 46 3. THE IDEOLOGY OF PUNK 52 3.1. ANARCHY 53 3.2. THE DIY ETHIC 56 3.3. ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS 59 3.4. GENDER AND SEXUALITY 62 3.5. PUNKS AND SKINHEADS 65 4. ANALYSIS OF LYRICS 68 4.1. “PUNK IS DEAD” 70 4.2. “NO GODS, NO MASTERS” 75 4.3. “ARE THESE OUR LIVES?” 77 4.4. “NAME AND ADDRESS WITHHELD”/“SUPERBOWL PATRIOT XXXVI (ENTER THE MENDICANT)” 82 EPILOGUE 89 APPENDIX – Alphabetical Collection of Song Lyrics Mentioned or Cited 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY 117 2 PREFACE Being a punk musician and lyricist myself, I have been following the development of punk rock for a good 15 years now. You might say that punk has played a pivotal role in my life. Needless to say, I have also seen a great deal of media misrepresentation over the years. I completely agree with Craig O’Hara’s perception when he states in his fine introduction to American punk rock, self-explanatorily entitled The Philosophy of Punk: More than Noise, that “Punk has been characterized as a self-destructive, violence oriented fad [...] which had no real significance.” (1999: 43.) He quotes Larry Zbach of Maximum RockNRoll, one of the better known international punk fanzines1, who speaks of “repeated media distortion” which has lead to a situation wherein “more and more people adopt the appearance of Punk [but] have less and less of an idea of its content. -

Music Express Song Index V1-V17

John Jacobson's MUSIC EXPRESS Song Index by Title Volumes 1-17 Song Title Contributor Vol. No. Series Theme/Style 1812 Overture (Finale) Tchaikovsky 15 6 Luigi's Listening Lab Listening, Classical 5 Browns, The Brad Shank 6 4 Spotlight Musician A la Puerta del Cielo Spanish Folk Song 7 3 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A la Rueda de San Miguel Mexican Folk Song, John Higgins 1 6 Corner of the World World Music A Night to Remember Cristi Cary Miller 7 2 Sound Stories Listening, Classroom Instruments A Pares y Nones Traditional Mexican Children's Singing Game, arr. 17 6 Let the Games Begin Game, Mexican Folk Song, Spanish A Qua Qua Jerusalem Children's Game 11 6 Kodaly in the Classroom Kodaly A-Tisket A-Tasket Rollo Dilworth 16 6 Music of Our Roots Folk Songs A-Tisket, A-Tasket Folk Song, Tom Anderson 6 4 BoomWhack Attack Boomwhackers, Folk Songs, Classroom A-Tisket, A-Tasket / A Basketful of Fun Mary Donnelly, George L.O. Strid 11 1 Folk Song Partners Folk Songs Aaron Copland, Chapter 1, IWMA John Jacobson 8 1 I Write the Music in America Composer, Classical Ach, du Lieber Augustin Austrian Folk Song, John Higgins 7 2 It's a Musical World! World Music Add and Subtract, That's a Fact! John Jacobson, Janet Day 8 5 K24U Primary Grades, Cross-Curricular Adios Muchachos John Jacobson, John Higgins 13 1 Musical Planet World Music Aeyaya balano sakkad M.B. Srinivasan. Smt. Chandra B, John Higgins 1 2 Corner of the World World Music Africa: Music and More! Brad Shank 4 4 Music of Our World World Music, Article African Ancestors: Instruments from Latin Brad Shank 3 4 Spotlight World Music, Instruments Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 8 4 Listening Map Listening, Classical, Composer Afro-American Symphony William Grant Still 1 4 Listening Map Listening, Composer Ah! Si Mon Moine Voulait Danser! French-Canadian Folk Song, John Jacobson, John 13 3 Musical Planet World Music Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around African-American Folk Song, arr. -

Volume 3, Number 11

Eastern Illinois University The Keep The Post Amerikan (1972-2004) The Post Amerikan Project 3-1975 Volume 3, Number 11 Post Amerikan Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/post_amerikan Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons narcs: a special supplement section; recession; more MARCH 1975 Bloomington ···Normal VOL. III No.11 BULK RATE U.S.. POSTAGE ADDRESS PAID CORRECTION NORMAL, ILL. REQUESTED 61?61 POST SELLERS BLOOMINGTON .Mail, which we more thar( wleome, c o me m ore than a reader. We welcome should be mailed toa The Post · all stories or tips for stories . The Joint, 415 N . Main Amerikan, 108 E. B eauf'ort St., Bring stuff to a meeting (the · DA' s :biquors , Oakland and Main Normal, Illinois, 61761. schedul e is printed below) or mail Medusa's Bookstore , 109 w. Front it to our office. Illinois We sle1an Uni on. Anyone can be a member of the Post News Nook, 402t N. Main staff e.xcept maybe Sheriff King . MEETINGS Book Hive, 103 w. Front All you have to do is come to the Cake Box, 511.S. Denver mee tings and do one of the many Mon., March 3, 8pm Gaston's Barber Shop , 202! N. Center different and ex c iting tasks nec Wed, , March 12, 8pm Sambo 's, Washington and u.s.66 essary for the s ooth o rating T DeVary's Market, 14o2 w. Market m pe ues . , March 18 , 8pm of a paper like this. -

Promokeyboarddisneybroch.Pdf

1 The magic of Disney’s music has touched people’s lives from generation to generation. From classic movie songs like “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” to new stars like the Jonas Brothers and Hannah Montana, Disney’s music has reached millions of people around the world. And the magic of Disney continues this fall when Walt Disney Animation Studios presents the musical Disney’s The Princess and the Frog, an animated comedy with music by Oscar®-winning composer Randy Newman set in the great city of New Orleans. From the creators of The Little Mermaid and Aladdin comes a modern twist on a classic tale, featuring a beautiful girl named Tiana (Anika Noni Rose), a frog prince who desperately wants to be human again, and a fateful kiss that leads them both on a hilarious adventure through the mystical bayous of Louisiana. To celebrate the magic of Disney’s music and Disney’s latest animated feature, The Princess and the Frog (in theatres 12.11.09) we want to send you to the movies! Call the Hal Leonard E-Z Order line at 1-800-554-0626 and place a qualifying order of $500 or more of any Disney products by 12/1/2009, and we’ll send you movie passes for a theatre near you! MATCHING FOLIOS ALADDIN Disney’s BeAUTY AND THE CHEEtaH GIRLS Matching folio to Disney’s animated THE BEAST: THE COLLECTION film featuring songs from Alan Men- BROADwaY MUSICAL with selections from ken, Howard Ashman and Tim Rice. A beautiful souvenir folio with color The Cheetah Girls and 7 songs in all, including: One Jump photos and production notes from The Cheetah Girls 2 Ahead • Prince Ali • Friend Like Me the Broadway spectacular as well as This hit Disney Channel movie stars • A Whole New World • and more. -

Music Express Song Index V1-V17

John Jacobson's MUSIC EXPRESS Song Index by Theme/Style Volumes 1-17 Song Title Contributor Vol. No. Series Theme/Style I've Got Peace Like a River African-American Spiritual, arr. Rollo Dilworth 15 1 Music of Our Roots African-American Spiritual Who Built the Ark? African-American Spritual, arr. Janet Day 15 4 Recorder Heroes & Sidekicks African-American Spiritual Over My Head Emily Crocker 16 1 Read & Sing Folk Songs African-American Spiritual, Folk Songs Angel Band, The Emily Crocker 16 3 Read & Sing Folk Songs African-American Spiritual, Folk Songs Good News Janet Day 16 4 Recorder Heroes & Sidekicks African-American Spiritual, Recorder, Pentatonix Janet Day, John Jacobson 17 1 One2One Video Interview Artist interview Aly & AJ, Do You Believe in Magic Janet Day 6 1 Spotlight Artist, Musician Signs and Symbols Cristi Cary Miller 17 5 Let the Games Begin Assessment, Review, Game Melody Hunt Cristi Cary Miller 17 4 Let the Games Begin Aural recognition, Game, Assessment, We Are Marching John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 7 2 Hop 'Til You Drop Back to School Right Here! Right Now! John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 8 1 Music Express in Concert Back to School Children of the World John Jacobson, Rollo Dilworth 9 1 Music Express in Concert Back to School New Beginning, A John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 9 4 Music Express in Concert Back to School Walk Faster! John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 10 5 Hop 'Til You Drop Back to School Planet Rock John Jacobson, Mac Huff 11 1 Music Express in Concert Back to School Let's Go! John Jacobson, Roger Emerson 12 1 Music -

Billy Joel's Turn and Return to Classical Music Jie Fang Goh, MM

ABSTRACT Fantasies and Delusions: Billy Joel’s Turn and Return to Classical Music Jie Fang Goh, M.M. Mentor: Jean A. Boyd, Ph.D. In 2001, the release of Fantasies and Delusions officially announced Billy Joel’s remarkable career transition from popular songwriting to classical instrumental music composition. Representing Joel’s eclectic aesthetic that transcends genre, this album features a series of ten solo piano pieces that evoke a variety of musical styles, especially those coming from the Romantic tradition. A collaborative effort with classical pianist Hyung-ki Joo, Joel has mentioned that Fantasies and Delusions is the album closest to his heart and spirit. However, compared to Joel’s popular works, it has barely received any scholarly attention. Given this gap in musicological work on the album, this thesis focuses on the album’s content, creative process, and connection with Billy Joel’s life, career, and artistic identity. Through this thesis, I argue that Fantasies and Delusions is reflective of Joel’s artistic identity as an eclectic composer, a melodist, a Romantic, and a Piano Man. Fantasies and Delusions: Billy Joel's Turn and Return to Classical Music by Jie Fang Goh, B.M. A Thesis Approved by the School of Music Gary C. Mortenson, D.M.A., Dean Laurel E. Zeiss, Ph.D., Graduate Program Director Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Approved by the Thesis Committee Jean A. Boyd, Ph.D., Chairperson Alfredo Colman, Ph.D. Horace J. Maxile, Jr., Ph.D. -

Connectnext® Infotainment System User's Manual

CONNECTNEXT® INFOTAINMENT SYSTEM USER’S MANUAL Dear Customer, Welcome to the CONNECTNEXT® Infotainment System User's Manual. The infotainment system in your vehicle provides you with state of the art in-car entertainment to enhance your driving experience. Before using the infotainment system for the first time, please ensure that you read this manual carefully. The manual will familiarize you with the infotainment system of your car and its functionalities. It also contains instructions on how to use the infotainment system in a safe and effective manner. We insist that all service and maintenance of the infotainment system of your car must be done only at authorized TATA service centers. Incorrect installation or servicing can cause permanent damage to the system. If you have any further questions about the infotainment system, please get in touch with the nearest Tata Dealership. We will be happy to answer your queries and value your feedback. We wish you a safe and connected drive! 1 CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 ABOUT THIS MANUAL 2 INTRODUCTION 3 GETTING STARTED Conventions .................................. 4 Control Elements Overview .....11 System ON/OFF............................ 38 Safety Guidelines......................... 5 Other Modes of Control.............19 Manage General Settings ......... 40 Trademarks ................................... 8 System Usage................................25 Change Audio Settings.............. 44 Warranty Clauses......................... 9 Change Volume Settings .......... 47 Software Details.......................... -

Erik Hanson & Keith Mayerson

they got a canvas, somehow it didn’t work. There was that E R I K H A N S O N & Blondie portrait last summer. Did you see that? It was up at KEITH MAYERSON [ DAVID ] Zwirner [ GALLERY ] . K E I T H : Oh, yeah. E R I K: That was fucking amazing! Keith Mayerson came to my studio for a chat shortly after his “Hamlet 2000” K E I T H : Maybe it was that stigma that graffiti has to be something that’s given away or illegal, and they couldn’t show opened at Derek Eller Gallery wrap their heads around it. I mean, Twist did okay. last fall. A very generous teacher, Keith immediately started critiquing E R I K: Who’s Twist? my latest graffiti paintings . K E I T H : Barry McGee, but that’s 90s graffiti. And he was a white guy from the suburbs. It looks good in here. When ERIK: Somehow the paintings are easier to do on paper, is your show in Kansas? on canvas . E R I K: March. Or, actually, the last day of February. K E I T H : Well, they look good to me. K E I T H : Are you psyched? E R I K: Thanks. E R I K: Yeah, totally, but I have a shitload of work to do. K E I T H : One of my students did this thing on graffiti It’s going to be these fifty birch logs, with records where and all the terms, like tags—and then there’s graffiti that the wood should be, and then five signs announcing per- you can’t read but there are letters for it.