Donald Harrison, Jr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

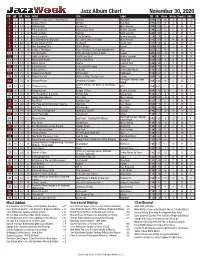

November 30, 2020 Jazz Album Chart

Jazz Album Chart November 30, 2020 TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW Move Weeks Reports Adds 1 1 1 1 Artemis 3 weeks at No. 1 / Most Reports Artemis Blue Note 310 291 19 10 51 0 2 2 2 1 Gregory Porter All Rise Blue Note 277 267 10 13 38 0 3 4 13 3 Yellowjackets Jackets XL Mack Avenue 259 236 23 5 49 4 4 7 6 4 Peter Bernstein What Comes Next Smoke Sessions 244 222 22 6 48 0 4 5 4 4 Javon Jackson Deja Vu Solid Jackson 244 235 9 7 47 1 6 6 8 5 Joe Farnsworth Time To Swing Smoke Sessions 229 229 0 9 40 0 7 8 3 1 Christian McBride Big Band For Jimmy, Wes and Oliver Mack Avenue 217 213 4 14 38 0 8 25 40 8 Brandi Disterheft Trio Surfboard Justin Time 211 155 56 3 47 3 9 9 15 9 Alan Broadbent Trio Trio In Motion Savant 209 206 3 5 47 2 10 14 12 10 Isaiah J. Thompson Plays The Music Of Buddy Montgomery WJ3 207 187 20 7 38 1 11 3 5 3 Conrad Herwig The Latin Side of Horace Silver Savant 203 242 -39 10 39 0 12 13 6 3 Eddie Henderson Shuffle and Deal Smoke Sessions 198 192 6 14 35 0 13 12 11 3 Kenny Washington What’s The Hurry Lower 9th 189 194 -5 14 34 1 14 10 13 6 Nubya Garcia Source Concord Jazz 188 199 -11 13 35 1 15 19 17 15 Ella Fitzgerald The Lost Berlin Tapes Verve 185 172 13 6 41 0 16 16 16 15 Chien Chien Lu The Path Chien Chien Music 175 185 -10 8 38 2 17 21 21 17 Uptown Jazz Tentet What’s Next Irabbagast 170 164 6 6 37 1 18 20 26 18 Richard Baratta Music In Film: The Reel Deal Savant 166 170 -4 4 40 1 Provogue / Mascot Label 19 30 78 19 George Benson Weekend in London Group 165 146 19 2 35 7 20 18 19 17 Teodross Avery Harlem Stories: -

Trumpeter Terence Blanchard

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Terence Blanchard PERSON Blanchard, Terence Alternative Names: Terence Blanchard; Life Dates: March 13, 1962- Place of Birth: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Work: New Orleans, LA Occupations: Trumpet Player; Music Composer Biographical Note Jazz trumpeter and composer Terence Oliver Blanchard was born on March 13, 1962 in New Orleans, Louisiana to Wilhelmina and Joseph Oliver Blanchard. Blanchard began playing piano at the age of five, but switched to trumpet three years later. While in high school, he took extracurricular classes at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. From 1980 to 1982, Blanchard studied at Rutgers University in New Jersey and toured with the Lionel Hampton Orchestra. In 1982, Blanchard replaced trumpeter Wynton Marsalis in Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, where he served as musical director until 1986. He also co- led a quintet with saxophonist Donald Harrison in the 1980s, recording five albums between 1984 and 1988. In 1991, Blanchard recorded and released his self-titled debut album for Columbia Records, which reached third on the Billboard Jazz Charts. He also composed musical scores for Spike Lee’s films, beginning with 1991’s Jungle Fever, and has written the score for every Spike Lee film since including Malcolm X, Clockers, Summer of Sam, 25th Hour, Inside Man, and Miracle At St. Anna’s. In 2006, he composed the score for Lee's four-hour Hurricane Katrina documentary for HBO entitled When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts. Blanchard also composed for other directors, including Leon Ichaso, Ron Shelton, Kasi Lemmons and George Lucas. -

The Jazz Record

oCtober 2019—ISSUe 210 YO Ur Free GUide TO tHe NYC JaZZ sCene nyCJaZZreCord.Com BLAKEYART INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY david andrew akira DR. billy torn lamb sakata taylor on tHe Cover ART BLAKEY A INDESTRUCTIBLE LEGACY L A N N by russ musto A H I G I A N The final set of this year’s Charlie Parker Jazz Festival and rhythmic vitality of bebop, took on a gospel-tinged and former band pianist Walter Davis, Jr. With the was by Carl Allen’s Art Blakey Centennial Project, playing melodicism buoyed by polyrhythmic drumming, giving replacement of Hardman by Russian trumpeter Valery songs from the Jazz Messengers songbook. Allen recalls, the music a more accessible sound that was dubbed Ponomarev and the addition of alto saxophonist Bobby “It was an honor to present the project at the festival. For hardbop, a name that would be used to describe the Watson to the band, Blakey once again had a stable me it was very fitting because Charlie Parker changed the Jazz Messengers style throughout its long existence. unit, replenishing his spirit, as can be heard on the direction of jazz as we know it and Art Blakey changed By 1955, following a slew of trio recordings as a album Gypsy Folk Tales. The drummer was soon touring my conceptual approach to playing music and leading a sideman with the day’s most inventive players, Blakey regularly again, feeling his oats, as reflected in the titles band. They were both trailblazers…Art represented in had taken over leadership of the band with Dorham, of his next records, In My Prime and Album of the Year. -

Tone Parallels in Music for Film: the Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra By

TONE PARALLELS IN MUSIC FOR FILM: THE COMPOSITIONAL WORKS OF TERENCE BLANCHARD IN THE DIEGETIC UNIVERSE AND A NEW WORK FOR STUDIO ORCHESTRA BY BRIAN HORTON Johnathan B. Horton B.A., B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Richard DeRosa, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Murphy, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Jazz Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Horton, Johnathan B. Tone Parallels in Music for Film: The Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra by Brian Horton. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 46 pp., 1 figure, 24 musical examples, bibliography, 49 titles. This research investigates the culturally programmatic symbolism of jazz music in film. I explore this concept through critical analysis of composer Terence Blanchard's original score for Malcolm X directed by Spike Lee (1992). I view Blanchard's music as representing a non- diegetic tone parallel that musically narrates several authentic characteristics of African- American life, culture, and the human condition as depicted in Lee's film. Blanchard's score embodies a broad spectrum of musical influences that reshape Hollywood's historically limited, and often misappropiated perceptions of jazz music within African-American culture. By combining stylistic traits of jazz and classical idioms, Blanchard reinvents the sonic soundscape in which musical expression and the black experience are represented on the big screen. -

National Endowment for the Arts Announces 2022 NEA Jazz Masters

July 20, 2021 Contacts: Liz Auclair (NEA), [email protected], 202-682-5744 Marshall Lamm (SFJAZZ), [email protected], 510-928-1410 National Endowment for the Arts Announces 2022 NEA Jazz Masters Recipients to be Honored on March 31, 2022, at SFJAZZ Center in San Francisco Washington, DC—For 40 years, the National Endowment for the Arts has honored individuals for their lifetime contributions to jazz, an art form that continues to expand and find new audiences through the contributions of individuals such as the 2022 NEA Jazz Masters honorees—Stanley Clarke, Billy Hart, Cassandra Wilson, and Donald Harrison Jr., recipient of the 2022 A.B. Spellman NEA Jazz Masters Fellowship for Jazz Advocacy. In addition to receiving a $25,000 award, the recipients will be honored in a concert on Thursday, March 31, 2022, held in collaboration with and produced by SFJAZZ. The 2022 tribute concert will take place at the SFJAZZ Center in San Francisco, California, with free tickets available for the public to reserve in February 2022. The concert will also be live streamed. More details will be available in early 2022. This will be the third year the NEA and SFJAZZ have collaborated on the tribute concert, which in 2020 and 2021 took place virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “The National Endowment for the Arts is proud to celebrate the 40th anniversary of honoring exceptional individuals in jazz with the NEA Jazz Masters class of 2022,” said Ann Eilers, acting chairman for the National Endowment of the Arts. “Jazz continues to play a significant role in American culture thanks to the dedication and artistry of individuals such as these and we look forward to working with SFJAZZ on a concert that will share their music and stories with a wide audience next spring.” Stanley Clarke (Topanga, CA)—Bassist, composer, arranger, producer Clarke’s bass-playing, showing exceptional skill on both acoustic and electric bass, has made him one of the most influential players in modern jazz history. -

Big Chief Donald Harrison Comes to the Big Apple

Big Chief Donald Harrison Comes To The Big Apple New Orleans Jazz Legend To Play NYC's Symphony Space by Tom Pryor April 16, 2012 Longtime Nat Geo Music readers must know by now that we are big, big fans of the HBO Original series Treme, and of the traditional musics and culture of New Orleans in general - especially NOLA's unique Mardi Gras Indian tradition. So it should be no surprise to find out that we were especially excited when we heard that saxman "Big Chief" Donald Harrison was coming to town this month - because Harrison is not only one of NOLA's most versatile and respected jazz artists; and he's not just another recurring, real-life fixture on Treme, but he's an honest-to-goodness "Big Chief" of the Congo Nation Afro- New Orleans Cultural Group - a direct link to the same tradition that brought us everything from the Wild Magnolias to the Dixie Cups. So you know it's gonna be a funky good time - and that the roots will run deep! An Evening with the Big Chief Donald Harrison is scheduled for Friday, April 27th, and New York's venerable Symphony Space, and will include a special guest performance by Grammy Nominated trumpeter Christian Scott. Here's what the official press release had to say about the event: Big Chief Donald Harrison merges the sounds of the New Orleans Jazz Fest and Big Apple Jazz with a special guest performance by Grammy Nominee Christian Scott. Big Chief Donald Harrison merges the sounds of the New Orleans Jazz Fest and Big Apple Jazz with a special guest performance by Grammy Nominee Christian Scott. -

1-15-20 the Messenger Legacy Honors Jazz Great Art Blakey at The

Media Contact: Barbara Hiller, Marketing Manager 301-600-2868 | [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Messenger Legacy Honors Jazz Great Art Blakey at the Weinberg Center FREDERICK, MD, Wednesday, January 15, 2020 — The Messenger Legacy – Art Blakey Centennial Celebration brings an all-star group of musicians to the Weinberg Center for the Arts on Friday, February 7, 2020 at 8:00 PM to play tribute to the Jazz Messengers, the big band collective led by the late Art Blakey. Tickets start at $20 and may be purchased online at WeinbergCenter.org, by calling the box office at 301- 600-2828, or in person at 20 West Patrick Street. Discounts are available for students, children, military, and seniors. Drummer Ralph Peterson Jr. has assembled an all-star group of musical talent for a tribute to the Jazz Messengers, the prolific big band collective led by his mentor, the late Art Blakey. Also the founding drummer, Blakely led the influential jazz collective from the mid-1950s until his death in 1990. This year the collective is marking the 100th anniversary of Blakey’s birth with selections from a new recording. The musicians include Peterson on percussion, saxophonists Bobby Watson and Bill Pierce, bassist Essiet Essiet, pianist Geoffrey Keezer, and trumpeter Brian Lynch. The Messenger Legacy can exist in several configurations. Musicians Phillip Harper, Robin Eubanks, Craig Handy, Donald Harrison, Johnny O’Neal, Lonnie Plaxico, Donald Brown and even the living senior Messenger Reggie Workman, are all connected to the project. Under the leadership of Blakey, the Jazz Messengers collective was a proving ground for young jazz talent, and that tradition continues today. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. ELLIS MARSALIS NEA Jazz Master (2011) Interviewee: Ellis Marsalis (November 14, 1934 - ) Interviewer: Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: November 8-9, 2010 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Description: Transcript, 79 pp. Brown: Today is November 8, 2010. This is the Smithsonian NEA Jazz Oral History interview with Ellis Marsalis, conducted by Anthony Brown, in his home at 3818 Hickory Street in New Orleans, Louisiana. Good evening, Ellis Marsalis. Marsalis: Good evening. Brown: It is truly a pleasure of mine to be able to conduct this interview with you. I have admired your work for a long time. This is, for me, a dream come true, to be able to talk to you face to face, as one music educator to another, as a jazz musician to another, as a father to another, to bring your contributions and your vision to light and have it documented for the American musical culture record. If we could start by you stating your full name at birth, and your birth date and place of birth please. Marsalis: My names Ellis Louis Marsalis, Jr. I was born in New Orleans, November 14, 1934. Brown: Your birthday’s coming up in a few days. Marsalis: Right. Brown: Wonderful. 1934. Could you give us the names of your parents, please? For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 1 Marsalis: Ellis Louis Marsalis, Sr. -

HOLLYWOOD BOWL 2016 SEASON Chronological Listing of Events

HOLLYWOOD BOWL 2016 SEASON Chronological Listing of Events JUNE 2016 PLAYBOY JAZZ FESTIVAL Saturday, June 11, at 3 PM (Non-subscription) PLAYBOY JAZZ FESTIVAL JOHN BATISTE & STAY HUMAN SETH MacFARLANE with conductor JOEL McNEELY CÉCILE McLORIN SALVANT LOS VAN VAN NATURALLY 7 THE BAD PLUS JOSHUA REDMAN JOEY ALEXANDER TRIO JOHN BEASLEY’S MONK’estra THE LAUSD/BEYOND THE BELL ALL-CITY JAZZ BIG BAND Under the Direction of Tony White and J.B. Dyas Master of Ceremonies GEORGE LOPEZ PLAYBOY JAZZ FESTIVAL Sunday, June 12, at 3 PM (Non-subscription) PLAYBOY JAZZ FESTIVAL FOURPLAY SILVER ANNIVERSARY with BOB JAMES, NATHAN EAST, CHUCK LOEB and HARVEY MASON JANELLE MONÁE THE ROBERT CRAY BAND Celebrates B.B. KING with special guests SONNY LANDRETH and ROY GAINES PETE ESCOVEDO ORCHESTRA featuring SHEILA E., JUAN and PETER MICHAEL JAVON JACKSON and SAX APPEAL featuring special guests JIMMY HEATH, GEORGE CABLES, PETER WASHINGTON, WILLIE JONES III BIG CHIEF DONALD HARRISON JR. and the CONGO NATION – NEW ORLEANS CULTURAL GROUP LIV WARFIELD CHRISTIAN SCOTT aTUNDE ADJUAH Presents STRETCH MUSIC ANTHONY STRONG CSUN JAZZ BAND directed by MATT HARRIS Master of Ceremonies GEORGE LOPEZ OPENING NIGHT AT THE Saturday, June 18, at 8 PM HOLLYWOOD BOWL *Fireworks* OPENING NIGHT at the BOWL with STEELY DAN (Non-subscription) HOLLYWOOD BOWL ORCHESTRA THOMAS WILKINS, conductor Steely Dan – with founders Walter Becker and Donald Fagan – performs with orchestra for the first time in this kick-off to the Bowl season, supporting music education. The Grammy®-winning Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Famers will treat audiences to their trend-setting jazz-rock blend has sold more than 40 million records, treat the audience to selections from The Dan’s four-decade catalog, rich with blazing solo work, infectious tunes, bodacious harmonies, irresistible grooves and sleek, subversive lyrics. -

We Offer Thanks to the Artists Who've Played the Nighttown Stage

www.nighttowncleveland.com Brendan Ring, Proprietor Jim Wadsworth, JWP Productions, Music Director We offer thanks to the artists who’ve played the Nighttown stage. Aaron Diehl Alex Ligertwood Amina Figarova Anne E. DeChant Aaron Goldberg Alex Skolnick Anat Cohen Annie Raines Aaron Kleinstub Alexis Cole Andrea Beaton Annie Sellick Aaron Weinstein Ali Ryerson Andrea Capozzoli Anthony Molinaro Abalone Dots Alisdair Fraser Andreas Kapsalis Antoine Dunn Abe LaMarca Ahmad Jamal ! Basia ! Benny Golson ! Bob James ! Brooker T. Jones Archie McElrath Brian Auger ! Count Basie Orchestra ! Dick Cavett ! Dick Gregory Adam Makowicz Arnold Lee Esperanza Spaulding ! Hugh Masekela ! Jane Monheit ! J.D. Souther Adam Niewood Jean Luc Ponty ! Jimmy Smith ! Joe Sample ! Joao Donato Arnold McCuller Manhattan TransFer ! Maynard Ferguson ! McCoy Tyner Adrian Legg Mort Sahl ! Peter Yarrow ! Stanley Clarke ! Stevie Wonder Arto Jarvela/Kaivama Toots Thielemans Adrienne Hindmarsh Arturo O’Farrill YellowJackets ! Tommy Tune ! Wynton Marsalis ! Afro Rican Ensemble Allan Harris The Manhattan TransFerAndy Brown Astral Project Ahmad Jamal Allan Vache Andy Frasco Audrey Ryan Airto Moreira Almeda Trio Andy Hunter Avashai Cohen Alash Ensemble Alon Yavnai Andy Narell Avery Sharpe Albare Altan Ann Hampton Callaway Bad Plus Alex Bevan Alvin Frazier Ann Rabson Baldwin Wallace Musical Theater Department Alex Bugnon Amanda Martinez Anne Cochran Balkan Strings Banu Gibson Bob James Buzz Cronquist Christian Howes Barb Jungr Bob Reynolds BW Beatles Christian Scott Barbara Barrett Bobby Broom CaliFornia Guitar Trio Christine Lavin Barbara Knight Bobby Caldwell Carl Cafagna Chuchito Valdes Barbara Rosene Bobby Few Carmen Castaldi Chucho Valdes Baron Browne Bobby Floyd Carol Sudhalter Chuck Loeb Basia Bobby Sanabria Carol Welsman Chuck Redd Battlefield Band Circa 1939 Benny Golson Claudia Acuna Benny Green Claudia Hommel Benny Sharoni Clay Ross Beppe Gambetta Cleveland Hts. -

Monterey Jazz Festival

DECEMBER 2018 VOLUME 85 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob; -

Donaldson, Your Full Name and Your Parents’ Names, Your Mother and Father

Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. LOU DONALDSON NEA Jazz Master (2012) Interviewee: Louis Andrew “Lou” Donaldson (November 1, 1926- ) Interviewer: Ted Panken with recording engineer Ken Kimery Dates: June 20 and 21, 2012 Depository: Archives Center, National Music of American History, Description: Transcript. 82 pp. [June 20th, PART 1, TRACK 1] Panken: I’m Ted Panken. It’s June 20, 2012, and it’s day one of an interview with Lou Donaldson for the Smithsonian Institution Oral History Jazz Project. I’d like to start by putting on the record, Mr. Donaldson, your full name and your parents’ names, your mother and father. Donaldson: Yeah. Louis Andrew Donaldson, Jr. My father, Louis Andrew Donaldson, Sr. My mother was Lucy Wallace Donaldson. Panken: You grew up in Badin, North Carolina? Donaldson: Badin. That’s right. Badin, North Carolina. Panken: What kind of town is it? Donaldson: It’s a town where they had nothing but the Alcoa Aluminum plant. Everybody in that town, unless they were doctors or lawyers or teachers or something, worked in the plant. Panken: So it was a company town. Donaldson: Company town. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] Page | 1 Panken: Were you parents from there, or had they migrated there? Donaldson: No-no. They migrated. Panken: Where were they from? Donaldson: My mother was from Virginia. My father was from Tennessee. But he came to North Carolina to go to college.