Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis

Thursday, September 29, 2016, 8pm Paramount Theatre, Oakland Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis Wynton Marsalis, music director, trumpet Ryan Kisor, trumpet Kenny Rampton, trumpet Marcus Printup, trumpet Vincent Gardner, trombone Chris Crenshaw, trombone Elliot Mason, trombone Sherman Irby, alto and soprano saxophones, flute, clarinet Ted Nash, alto and soprano saxophones, flute, clarinet Victor Goines, tenor and soprano saxophones, clarinet, bass clarinet Walter Blanding, tenor and soprano saxophones, clarinet Paul Nedzela, baritone and soprano saxophones, bass clarinet Dan Nimmer, piano Carlos Henriquez, bass Ali Jackson, drums Tonight’s program will be announced from the stage and performed without an intermission. Brooks Brothers is the official clothier of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis. For more information, please visit jazz.org. Facebook: facebook.com/jazzatlincolncenter Twitter: twitter.com/jazzdotorg YouTube: youtube.com/jazzatlincolncenter Cal Performances' presentations in Oakland are generously underwritten by Signature Development Group. Jazz residency and education activities are generously underwritten by the Thatcher Meyerson Family. ABOUT THE ARTISTS he mission of Jazz at Lincoln Center is country, woven with the colorful stories of the to entertain, enrich, and expand a global artists behind them. Jazz Night in America and Tcommunity for jazz through perform- Jazz at Lincoln Center’s radio archive can be ance, education, and advocacy. With the found at jazz.org/radio. world-renowned Jazz at Lincoln Center Orch - Under music director Wynton Marsalis, the estra and guest artists spanning genres and JLCO spends over a third of the year on tour. generations, Jazz at Lincoln Center produces The big band performs a vast repertoire, from thousands of performance, education, and rare historic compositions to Jazz at Lincoln broadcast events each season in its home in Center-commissioned works, including com- New York City (Frederick P. -

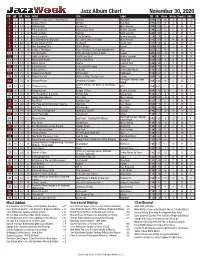

November 30, 2020 Jazz Album Chart

Jazz Album Chart November 30, 2020 TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW Move Weeks Reports Adds 1 1 1 1 Artemis 3 weeks at No. 1 / Most Reports Artemis Blue Note 310 291 19 10 51 0 2 2 2 1 Gregory Porter All Rise Blue Note 277 267 10 13 38 0 3 4 13 3 Yellowjackets Jackets XL Mack Avenue 259 236 23 5 49 4 4 7 6 4 Peter Bernstein What Comes Next Smoke Sessions 244 222 22 6 48 0 4 5 4 4 Javon Jackson Deja Vu Solid Jackson 244 235 9 7 47 1 6 6 8 5 Joe Farnsworth Time To Swing Smoke Sessions 229 229 0 9 40 0 7 8 3 1 Christian McBride Big Band For Jimmy, Wes and Oliver Mack Avenue 217 213 4 14 38 0 8 25 40 8 Brandi Disterheft Trio Surfboard Justin Time 211 155 56 3 47 3 9 9 15 9 Alan Broadbent Trio Trio In Motion Savant 209 206 3 5 47 2 10 14 12 10 Isaiah J. Thompson Plays The Music Of Buddy Montgomery WJ3 207 187 20 7 38 1 11 3 5 3 Conrad Herwig The Latin Side of Horace Silver Savant 203 242 -39 10 39 0 12 13 6 3 Eddie Henderson Shuffle and Deal Smoke Sessions 198 192 6 14 35 0 13 12 11 3 Kenny Washington What’s The Hurry Lower 9th 189 194 -5 14 34 1 14 10 13 6 Nubya Garcia Source Concord Jazz 188 199 -11 13 35 1 15 19 17 15 Ella Fitzgerald The Lost Berlin Tapes Verve 185 172 13 6 41 0 16 16 16 15 Chien Chien Lu The Path Chien Chien Music 175 185 -10 8 38 2 17 21 21 17 Uptown Jazz Tentet What’s Next Irabbagast 170 164 6 6 37 1 18 20 26 18 Richard Baratta Music In Film: The Reel Deal Savant 166 170 -4 4 40 1 Provogue / Mascot Label 19 30 78 19 George Benson Weekend in London Group 165 146 19 2 35 7 20 18 19 17 Teodross Avery Harlem Stories: -

Wavelength (December 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1981 Wavelength (December 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1981) 14 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ML I .~jq Lc. Coli. Easy Christmas Shopping Send a year's worth of New Orleans music. to your friends. Send $10 for each subscription to Wavelength, P.O. Box 15667, New Orleans, LA 10115 ·--------------------------------------------------r-----------------------------------------------------· Name ___ Name Address Address City, State, Zip ___ City, State, Zip ---- Gift From Gift From ISSUE NO. 14 • DECEMBER 1981 SONYA JBL "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " meets West to bring you the Ernie K-Doe, 1979 East best in high-fideUty reproduction. Features What's Old? What's New ..... 12 Vinyl Junkie . ............... 13 Inflation In Music Business ..... 14 Reggae .............. .. ...... 15 New New Orleans Releases ..... 17 Jed Palmer .................. 2 3 A Night At Jed's ............. 25 Mr. Google Eyes . ............. 26 Toots . ..................... 35 AFO ....................... 37 Wavelength Band Guide . ...... 39 Columns Letters ............. ....... .. 7 Top20 ....................... 9 December ................ ... 11 Books ...................... 47 Rare Record ........... ...... 48 Jazz ....... .... ............. 49 Reviews ..................... 51 Classifieds ................... 61 Last Page ................... 62 Cover illustration by Skip Bolen. Publlsller, Patrick Berry. Editor, Connie Atkinson. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI NEA Jazz Master (2007)

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. TOSHIKO AKIYOSHI NEA Jazz Master (2007) Interviewee: Toshiko Akiyoshi 穐吉敏子 (December 12, 1929 - ) Interviewer: Dr. Anthony Brown with recording engineer Ken Kimery Dates: June 29, 2008 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript 97 pp. Brown: Today is June 29th, 2008, and this is the oral history interview conducted with Toshiko Akiyoshi in her house on 38 W. 94th Street in Manhattan, New York. Good afternoon, Toshiko-san! Akiyoshi: Good afternoon! Brown: At long last, I‟m so honored to be able to conduct this oral history interview with you. It‟s been about ten years since we last saw each other—we had a chance to talk at the Monterey Jazz Festival—but this interview we want you to tell your life history, so we want to start at the very beginning, starting [with] as much information as you can tell us about your family. First, if you can give us your birth name, your complete birth name. Akiyoshi: To-shi-ko. Brown: Akiyoshi. Akiyoshi: Just the way you pronounced. Brown: Oh, okay [laughs]. So, Toshiko Akiyoshi. For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 Akiyoshi: Yes. Brown: And does “Toshiko” mean anything special in Japanese? Akiyoshi: Well, I think,…all names, as you know, Japanese names depends on the kanji [Chinese ideographs]. Different kanji means different [things], pronounce it the same way. And mine is “Toshiko,” [which means] something like “sensitive,” “susceptible,” something to do with a dark sort of nature. -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Irene Kral Wonderful Life Mp3, Flac, Wma

Irene Kral Wonderful Life mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Pop Album: Wonderful Life Country: US Released: 1965 Style: Vocal MP3 version RAR size: 1130 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1217 mb WMA version RAR size: 1235 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 695 Other Formats: FLAC MP3 MP2 MMF AA AAC VQF Tracklist Hide Credits Wonderful Life A1 1:40 Written-By – David Perrin, L. Boxer* Thre Are Days When I Don't Think Of You At All A2 2:42 Written-By – F. Landesman*, T. Wolf* There Is No Right Way A3 2:20 Written-By – R. Batchelor*, T. Wolf* Goin' To California A4 2:30 Written-By – B. Loughborough*, David Wheat Is It Over Baby? A5 2:30 Written-By – Virginia Fitting I've Never Been Anything A6 2:45 Written-By – T. Wolf* Sometime Ago B1 3:09 Written-By – Sergio Michanovich* Nothing Like You B2 2:20 Written-By – B. Dorough*, F. Landesman* Here I Go Again B3 2:55 Written-By – C. Coleman*, T. Wolf* Mad At The World B4 1:50 Written-By – B. Florence*, F. Manley* This Life We've Led B5 3:52 Written-By – F. Landesman*, N. ALgren*, T. Wolf* Hold Your Head High B6 2:00 Written-By – J. De Shannon*, R. Newman* Credits Artwork [Cover Art], Design – Jack Lonshein Bass – Chuck Berghofer, Jimmy Bond Drums – Hal Blaine Engineer – Chuck Britz, Hal "Lanky" Linstrot* Flugelhorn – Joe Burnett Guitar – Dennis Budimir, Donald Peake*, Ervan Coleman, Mike Deasy Liner Notes – John Gottlieb Mastered By – Hal Diepold Percussion – Emil Richards, Gene Estes Piano – Al De Lory, Russ Freeman Saxophone – Gene Cipriano Trombone [Bass Trombone] – Richard Leith Trumpet – Ollie Mitchell Vocals – Irene Kral Notes Also released in Mono . -

Trumpeter Terence Blanchard

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Terence Blanchard PERSON Blanchard, Terence Alternative Names: Terence Blanchard; Life Dates: March 13, 1962- Place of Birth: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Work: New Orleans, LA Occupations: Trumpet Player; Music Composer Biographical Note Jazz trumpeter and composer Terence Oliver Blanchard was born on March 13, 1962 in New Orleans, Louisiana to Wilhelmina and Joseph Oliver Blanchard. Blanchard began playing piano at the age of five, but switched to trumpet three years later. While in high school, he took extracurricular classes at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts. From 1980 to 1982, Blanchard studied at Rutgers University in New Jersey and toured with the Lionel Hampton Orchestra. In 1982, Blanchard replaced trumpeter Wynton Marsalis in Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, where he served as musical director until 1986. He also co- led a quintet with saxophonist Donald Harrison in the 1980s, recording five albums between 1984 and 1988. In 1991, Blanchard recorded and released his self-titled debut album for Columbia Records, which reached third on the Billboard Jazz Charts. He also composed musical scores for Spike Lee’s films, beginning with 1991’s Jungle Fever, and has written the score for every Spike Lee film since including Malcolm X, Clockers, Summer of Sam, 25th Hour, Inside Man, and Miracle At St. Anna’s. In 2006, he composed the score for Lee's four-hour Hurricane Katrina documentary for HBO entitled When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts. Blanchard also composed for other directors, including Leon Ichaso, Ron Shelton, Kasi Lemmons and George Lucas. -

Trumpeter Scotty Barnhart Appointed New Director of the Count Basie Orchestra

September 23, 2013 To: Listings/Critics/Features From: Jazz Promo Services Press Contact: Jim Eigo, [email protected] www.jazzpromoservices.com Trumpeter Scotty Barnhart Appointed New Director of The Count Basie Orchestra For Immediate Release The Count Basie Orchestra and All That Music Productions, LLC, is pleased to announce the appointment of Scotty Barnhart as the new Director of The Legendary Count Basie Orchestra. He follows Thad Jones, Frank Foster, Grover Mitchell, Bill Hughes, and Dennis Mackrel in leading one of the greatest and most important jazz orchestras in history. Founded in 1935 by pianist William James Basie (1904-1984), the orchestra still tours the world today and is presently ending a two-week tour in Japan. The orchestra has released hundreds of recordings, won every respected jazz poll in the world at least once, has appeared in movies, television shows and commercials, Presidential Inaugurals, and has won 18 Grammy Awards, the most for any jazz orchestra. Many of its former members are some of the most important soloists, vocalists, composers, and arrangers in jazz history. That list includes Lester Young, Billie Holiday, Harry “Sweets” Edison, Jo Jones, Frank Foster, Frank Wess, Thad Jones, Joe Williams, Sonny Payne, Snooky Young, Al Grey, John Clayton, Dennis Mackrel and others. Mr. Barnhart, born in 1964, is a native of Atlanta, Georgia. He discovered his passion for music at an early age while being raised in Atlanta's historic Ebenezer Baptist Church where he was christened by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.He has been a featured trumpet soloist with the Count Basie Orchestra for the last 20 years, and has also performed and recorded with such artists as Wynton Marsalis, Marcus Roberts, Frank Sinatra, Diana Krall, Clark Terry, Freddie Hubbard, The Duke Ellington Orchestra, Nat Adderley, Quincy Jones, Barbara Streisand, Natalie Cole, Joe Williams, and many others. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

The B-G News April 14, 1967

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-14-1967 The B-G News April 14, 1967 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The B-G News April 14, 1967" (1967). BG News (Student Newspaper). 2083. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/2083 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Helwig, Brown Victorious Rick Helwig and Ashley Brown, Ively, In Wednesday's all* campus (Ind.), 139. 659 votes, Jean Schober (UP), Elected Sophomore Class Stu- both University Party candidates, elections. Keith Mabee (UP) was elected 517 votes, and Paul Buehrer (UP), dent Council representatives were were elected student body pres- Junior Class vice president. Mabee 557 votes. Other candidates for Sue Schaefer (UP), 744 votes, ident and vice president, respect- Helwig easily defeated T. David received 404 votes and his op- the office were Bob Alexander Wendy Whitlinger (UP), 635 votes Evans, an Independent candidate, ponents, Ken Mack (Ind.), John (CIP), 413 votes, Jim Ccffman and Joe Loomis (Ind.), 556 votes. by a 2,516 to 1,096 margin. Brown Pomeroy (CIH) and Charles Jack- (UP), 282 votes.JaneLowell(CIP), Other candidates for Sophomore had more trouble, edging out J eff son (Ind.), received 291, 275 and 236 votes and William Moes(Ind-), Class representative were Terry Wltjas of the Campus Interest 110 votes, respectively.