Kawarau/Remarkables Conservation Area Historicheritage Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queenstown Lakes District Plan Review, Chapter 26: Historic Heritage

DISTRICT PLAN REVIEW CHAPTER 26: HISTORIC HERITAGE SUBMISSION TO THE QUEENSTOWN LAKES DISTRICT COUNCIL 23 OCTOBER 2015 1. BACKGROUND TO IPENZ The Institution of Professional Engineers New Zealand (IPENZ) is the lead national professional body representing the engineering profession in New Zealand. It has approximately 16,000 Members, and includes a cross-section of engineering students, practising engineers, and senior Members in positions of responsibility in business. IPENZ is non-aligned and seeks to contribute to the community in matters of national interest giving a learned view on important issues, independent of any commercial interest. As the lead engineering organisation in New Zealand, IPENZ has responsibility for advocating for the protection and conservation of New Zealand’s engineering heritage. IPENZ manages a Heritage Register and a Heritage Record for engineering items throughout New Zealand. The IPENZ Engineering Heritage Register has criteria and thresholds similar to Category 1 historic places on Heritage New Zealand’s New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero. Items on our Register have been assessed as being engineering achievements of outstanding or special heritage significance. IPENZ is still populating the Register. The IPENZ Engineering Heritage Record includes histories of industrial and engineering items around New Zealand, and is also subject to ongoing improvements and additions. 2. GENERAL COMMENTS 2.1 INTRODUCTION The scheduling of heritage places in the District Plans of local authorities is an important mechanism that IPENZ supports because of our objective of promoting the protection, preservation and conservation of New Zealand’s engineering heritage. The Queenstown Lakes District has a very rich heritage and in particular has a wealth of industrial and engineering heritages sites because of the area’s early mining, agricultural and pastoral history and its challenging topography. -

Growing Plants in the Wakatipu

The Wakatipu Basin has some of the most unique and adaptive groups of plants found anywhere on the planet. Extensive modification of our landscape has seen these plants all but disappear from large parts of the basin. However, the importance of native species in New Zealand is being gradually recognised, and the importance of plants in the Wakatipu Basin is no exception. Many in the past have considered native plants slow growing and poorly adaptive, but the truth is the complete opposite. Native species found in the basin have had millions of years to adapt to its harsh, but beautiful terrain. It is important for anyone considering planting to determine what plants are right for this area so they can not only thrive, but help increase biodiversity values and bring back the native birds. This practical guide has been written to help anyone who is interested in planting native species within the Wakatipu Basin. It tells the story of the region, and explains how to best enhance one’s garden or patch of land. It includes helpful tips that will improve the success of any native plantings, particularly when considering sites encompassing the challenging micro-climates found throughout the district. It provides helpful advice to the first time gardener or the seasoned pro. It covers all aspects of planting, including maintenance advice and plant lists, so that even the most amateur gardener can soon have a thriving native patch filled with native bird song. Growing Native Plants in the Wakatipu Published by the Wakatipu Reforestation Trust (WRT) www.wrtqt.org.nz Email: [email protected] First Published 2017 The WRT has many volunteering ©Wakatipu Reforestation Trust 2017 opportunities. -

Wakatipu Trails Strategy

Wakatipu Trails Strategy Prepared for: Wakatipu Trails Trust Prepared by: Tourism Resource Consultants in association with Natural Solutions for Nature Ltd and Beca Carter Hollings and Ferner Ltd May 2004 Wakatipu Trails Strategy: TRC, May 2004 Page Table of Contents No. Executive Summary 2 Section 1. Introduction 7 Section 2. The Current Situation – Where Are We Now? 9 Section 3. A Vision for the Trails in the Wakatipu Basin 14 Section 4. Strategic Goals 15 Section 5. Priorities and Estimated Development Costs 29 Section 6A. Implementation Plan - Summary 33 Section 6B. Implementation Plan - Arterial Trails for 34 Walking and Cycling Section 6C. Implementation Plan - Recreational Trails 35 Section 6D. Implementation Plan – Management 36 Implications Appendix 1. Indicative Standards of the Wakatipu Trails 39 Network Appendix 2. Recreational User Requirements for the Rural 42 Road Network Appendix 3. Potential Public Access Network 46 1 1 Wakatipu Trails Strategy: TRC, May 2004 Executive The strategy was prepared to guide development of an integrated Summary network of walking and cycling trails and cycle-ways in the Wakatipu Basin. Preparation of the strategy was initiated by the Wakatipu Trails Trust in association with Transfund and Queenstown Lakes District Council. Funding was provided by Transfund and Council. The Department of Conservation and Otago Regional Council have also been key parties to the strategy. Vision The strategy’s vision – that of creating a world class trail and cycle network - is entirely appropriate given the scenic splendour, international profile and accessibility of the Wakatipu Basin. At its centre, Queenstown is New Zealand’s premier tourist destination. Well known for bungy jumping, rafting, skiing and jet boating, it has the informal status of being this country’s ‘adventure capital’. -

Queenstown and Surrounds (Wakatipu Area)

Community – Kea Project Plan Queenstown and Surrounds (Wakatipu area) Funded by: Department of Conservation – Community Fund (DOC-CF) Period: 1 December 2015 – 31 October 2017. Key contact person: Kea Conservation Trust – Tamsin Orr-Walker – [email protected]; Ph 0274249594 Aim The aim of the Community – Kea Project Plan is to i) facilitate long-term community kea conservation initiatives and ii) to change the way we think, act and live with kea in our communities. This will be actioned through development of collaborative Project Plans across the South Island. Each community plan will address concerns specific to the local community and threats to the resident kea population. Project Background This initial project plan outline has been developed as a result of discussions with communities during the Kea Conservation Trust’s (KCT) Winter Advocacy Tour - 20 July – 3 August 2015. The tour was funded by Dulux and supported by Department of Conservation (DOC). The tour theme, “Building a future with kea”, aimed to promote a new MOU between communities and kea. This initiative is in line with the new Strategic Plan for Kea Conservation (refer attached draft document), objective 3: to i) increase positive perceptions of kea and reduce conflict and ii) facilitate formation of community led kea conservation initiatives. Local Community – Kea Project Plans will be activated by two Community Engagement Coordinator’s (CEC’s) based in the following areas: 1) Upper half of the South Island: Northern region (Nelson/ Motueka/ Kahurangi), Central North (Nelson Lakes/ Murchison/Arthur’s Pass/Christchurch/Mt Hutt) and upper West Coast (Greymouth and Hokitika). -

Kelvin Peninsula // Jack's Point

KELVIN PENINSULA // JACK’S POINT Community Response Plan contents... Kelvin Peninsula / Kelvin Peninsula / Jack’s Point Area Map 3 Jack’s Point Evacuation Routes 18 Key Hazards 4 Earthquake 4 Plan Activation Process 19 Major Storms / Snowstorms 4 Civil Defence Centres 19 Wildfire 4 Roles and responsibilities 19 Landslide 5 Accident 5 Vulnerable Population Site 20 Household Emergency Plan 6 Kelvin Peninsula Tactical Sites Map 21 Emergency Survival Kit 7 Getaway Kit 7 Jack’s Point Stay in touch 7 Tactical Sites Map 22 Earthquake 8 Lakeside Estate Before and during an earthquake 8 & Wye Creek After an earthquake 9 Tactical Sites Map 23 Post disaster building management 9 Kelvin Peninsula Major Storms / Civil Defence Centres Map 24 Snowstorms 10 Before and when a warning is issued 10 After a storm, snowstorms 11 Jack’s Point Civil Defence Centres Map 25 Wildfires 12 Before and during 12 Visitor, Tourist and After a fire 13 Foreign National Welfare 26 Fire seasons 13 Emergency Contacts 27 Landslide 14 Before and during 14 After a landslide 15 For further information 28 Danger signs 15 Road Transport Crashes 16 Before, during and after 16 Truck crash zones maps 17 2 get ready... KELVIN PENINSULA / JACK’S POINT Area Map 6A KELVIN HEIGHTS JACK’S POINT 6 LAKESIDE ESTATE 3 get ready... THE KEY HAZARDS IN KELVIN PENINSULA & JACK’S POINT Earthquake // Major Storms // Snowstorms Wildfire // Landslide // Accident Earthquake New Zealand lies on the boundary of the Pacific and Australian tectonic plates. Most earthquakes occur at faults, which are breaks extending deep within the earth, caused by movements of these plates. -

Resource Consent Applications Received for the Queenstown Lakes District

RESOURCE CONSENT APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR THE QUEENSTOWN LAKES DISTRICT QUEENSTOWN LAKES DISTRICT COUNCIL INFORMATION SERVICE Private Bag 50072 QUEENSTOWN 9348 T: 03 441 0499 F: 03 450 2223 [email protected] www.qldc.govt.co.nz © Copyright 01.09.17 - 30.09.17 RC NO APPLICANT & PROPOSAL ZONE STATUS RM161129 RCL HENLEY DOWNS LTD - A SUBDIVISION CREATING 160 RESIDENTIAL ALLOTMENTS AND LAND USE CONSENT TO ERECT DWELLINGS RSV Decision Issued BREACHING INTERNAL SETBACKS AND HEIGHT RECESSION PLANES WITHIN STAGES 1 AND 2 AT WOOLSHED ROAD, JACKS POINT RM170030 THE LOCAL LOCKUP LIMITED - TO CONSTRUCT A STORAGE BUILDING THAT WILL BREACH BUILDING HEIGHT AND ABOVE GROUND SIGNAGE IND2 Waiting for Further AND TO CANCEL CONDITIONS B, C AND H OF CONSENT NOTICE 6946342.1 AT 13 FREDRICK STREET, WANAKA Information RM170060 SUBURBAN ESTATES LIMITED MP Decision Issued RM170074 P, V & L WEST & WF TRUSTEES 2004 LTD & J, J & D HEALEY - S127 CHANGE TO CONDITION 1 OF RM150785 TO AMEND SITE & LOCATION OF RG Formally Received ACCESS, & S221 APPLICATION TO CHANGE CONDITION D) OF CN 9746624.4 TO ALLOW ALTERNATIVE ACCESS AT 62 ARROW JUNCTION ROAD, ARROWTOWN RM170523 K & J ROBERTS - LAND USE TO CONSTRUCT AN ACCESSORY BUILDING OUTSIDE OF AN APPROVED RESIDENTIAL BUILDING PLATFORM AT 3 RG Formally Received MORRIS ROAD, WANAKA RM170531 A & H PURDON - TO CONSTRUCT A GARAGE IN THE ROAD BOUNDARY SETBACK, AND INFRINGE BOUNDARY SETBACKS WITH A LD Decision Issued BALCONY/PATIO AREA AND RETAINING WALLS AND UNDERTAKE EARTHWORKS ASSOCIATED WITHIN CONSTRUCTION OF A RESIDENTIAL -

Notified Applications and Decisions from the Commission

NOTIFIED APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS FROM THE COMMISSION To view the full application and the decision (if applicable), please search in eDocs using the resource consent reference. https://edocs.qldc.govt.nz/ CONSENT PROPOSAL D Brown & R Venning Consent to undertake a 2 lot subdivision at 752 Malaghans Road, Queenstown. RM210167 D & S Brent Consent to undertake a 3 lot subdivision at Riverbank Road, Wanaka. Legally described as Lot 3 Deposited Plan RM210037 383485 held in Record of Title 333154. J & R Knight Consent to undertake a two lot subdivision at 11 Northburn Road, Wanaka. RM210092 Bigavision Limited 34.56m2 digital billboard displaying static messages 93 Beach Street, Queenstown. RM201003 J & C Erkkila Family Trust Construct a new residential unit at Kinross Winery, 2300 Gibbston Highway, Queenstown. RM200879 J & K Timu and H Simmers Consent to undertake a two lot subdivision and establish a new building platform on Lot 2 at 89 Black Peak Road, RM200872 Wanaka R Kerjiwal, P Chi Chen & Gq To undertake visitor accommodation activities from an existing residential unit at 44B Highview Terrace, Trustees 2018 Limited Queenstown RM200967 K & J Butson Consent to undertake a five-lot rural subdivision at Wanaka Luggate Highway, Wanaka, legally described as Lot 7 RM200946 Deposited Plan 24216. NZDL Trustee Limited To construct 11 units in the form of airstream caravans and undertake 365 nights per year of short term Visitor RM200608 Accommodation 18 Orchard Road, Wanaka. Waterfall Park Developments Ltd To identify an 801m2 building platform 339 Arrowtown - Lake Hayes Road and Ayr Avenue, Arrowtown. RM200791 Skyline Enterprises Limited To change Condition 72 of resource consent RM171172 to allow the use of shotcrete for slope stabilisation to a RM200880 height approximately 27.5m above the consented car park building at Ben Lomond Recreation Reserve, Brecon St, Queenstown . -

Playing Around New Zealand Ltd 64 Pine Harbour Parade Beachlands, Auckland

Playing Around New Zealand Ltd 64 Pine Harbour Parade Beachlands, Auckland, New Zealand Ph. +64 9 5364560 E. [email protected] Kiwi Specials, June - October 2020 Queenstown – 6 Days PACKAGE INCLUSIONS • 4 rounds of golf (Millbrook, Queenstown GC, Arrowtown and Jack’s Point) • 5 night’s accommodation in listed accommodation. • Electric carts at each golf course. • Airport and golf transfers in luxury touring vehicle with professional driver / guide. • 24 hour on-call assistance from the Playing Around New Zealand tour office. • New Zealand goods & services tax (GST) at 15% COSTS (Based on a group of 8 New Zealand based golfers) • NZ$1250 per person (own room in 2 or 3 bedroom apartment) • NZ$1050 per person (share room in 2 or 3 bedroom apartment) Schedule Day 1: Arrive Queenstown Morning / Afternoon: Arrive in Queenstown off flight ______ at _______. We will meet your group at the airport and provide the transfer to central Queenstown. Evening: At leisure in Queenstown. Accommodation: The Glebe Apartments, 2 & 3 Bedroom Apartments x 5 nights Day 2: Queenstown Morning: Golf at Millbrook. Tee Time: 11:00am Your transport will depart the hotel at 9:45am and the driver will return to the course at 4:00pm Evening: At leisure in Queenstown. Day 3: Queenstown Morning: Golf at Queenstown GC (Kelvin Heights). Tee time: 11:00am Your transport will depart the hotel at 10:00am. The driver will return to the course at 4:00pm Evening: At leisure at Queenstown. Day 4: Queenstown Morning: Golf at Arrowtown. Tee Time: 11:00am Your transport will depart the hotel at 10am and the driver will return to the course at 3:30pm. -

Resource Consent Applications Received for the Queenstown Lakes District

RESOURCE CONSENT APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FOR THE QUEENSTOWN LAKES DISTRICT QUEENSTOWN LAKES DISTRICT COUNCIL INFORMATION SERVICE Private Bag 50072 QUEENSTOWN 9348 T: 03 441 0499 F: 03 450 2223 [email protected] www.qldc.govt.co.nz © Copyright 01.01.19 – 31.01.19 RC NO APPLICANT & PROPOSAL ZONE STATUS S & J MCLEOD - EXTENSION OF TIME - EXTENSION OF TIME APPLICATION, IN ORDER TO EXTEND THE LAPSE DATE OF RM130891 BY 5 YEARS AT WOODBURY RISE, ET130891 QUEENSTOWN LD Formally Received RM180359 P & S NEWSOME - AMEND AN AMALGAMATION CONDITION BY WAY OF S226 AT 237 ARROWTOWN-LAKE HAYES ROAD, WAKATIPU BASIN RRES Processing Application J & C OLIVIER - CONSTRUCT A RESIDENTIAL FLAT, AND GARAGE IN THE ROAD AND INTERNAL BOUNDARY SETBACK AND TO CHANGE 7067811.12 CONDITION A AND RM181022 CONDITION 6(A) OF RM050587 TO BUILD OUTSIDE THE BUILDING PLATFORM AT 8 HERRIES LN, LAKE HAYES ESTATE RRES Decision Issued SOUTHLAND DISTRICT COUNCIL - ERECTION OF EMERGENCY SHELTERS AND TOILETS ON SITES ADJACENT TO VON ROAD AND MOUNT NICHOLAS ROAD, MOUNT RM181162 NICHOLAS RG In Progress Wating for Further RM181503 B & J NIMMO - APPLICATION TO CONVERT AN EXISTING BARN INTO A RESIDENTIAL FLAT AT 286C BALLANTYNE ROAD, WANAKA RG Information M & K JENNINGS - 2 LOT SUBDIVISION WITH ONE LOT THAT WILL BE SMALLER THAN THE MINIMUM LOT SIZE AND A CHANGE TO CONSENT NOTICE CONDITIONS AT 972 RM181522 AUBREY ROAD, WANAKA RRES Decision Issued ALPHA PROPERTIES LIMITED - TO UTILISE THE PROPOSED UNITS 11 AND 14 FOR VISITOR ACCOMMODATION AT UNITS 11 & 14 THE TIERS, POTTERS HILL DRIVE, -

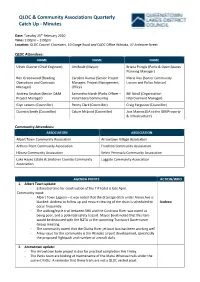

QLDC & Community Associations Quarterly Catch Up

QLDC & Community Associations Quarterly Catch Up - Minutes Date: Tuesday 25th February 2020 Time: 1:00pm – 3:00pm Location: QLDC Council Chambers, 10 Gorge Road and QLDC Office Wānaka, 47 Ardmore Street QLDC Attendees: NAME NAME NAME Ulrich Glasner (Chief Engineer) Jim Boult (Mayor) Briana Pringle (Parks & Open Spaces Planning Manager) Ben Greenwood (Roading Caroline Dumas (Senior Project Marie Day (Senior Community Operations and Contracts Manager, Project Management Liaison and Policy Advisor) Manager) Office) Andrew Strahan (Senior O&M Samantha Marsh (Parks Officer – Bill Nicoll (Organisation Project Manager) Volunteers/Community) Improvement Manager) Glyn Lewers (Councillor) Penny Clark (Councillor) Craig Ferguson (Councillor) Quentin Smith (Councillor) Calum McLeod (Councillor) Jess Mannix (EA to the GM Property & Infrastructure) Community Attendees: ASSOCIATION ASSOCIATION Albert Town Community Association Arrowtown Village Association Arthurs Point Community Association Frankton Community Association Hāwea Community Association Kelvin Peninsula Community Association Lake Hayes Estate & Shotover Country Community Luggate Community Association Association AGENDA POINTS ACTION/WHO 1. Albert Town update: - Estimated time for construction of the TIF toilet is late April. Community input: - Albert Town Lagoon – it was noted that the drainage ditch under Alison Ave is blocked. Andrew to follow up and ensure clearing of the drain is scheduled to Andrew occur frequently. - The walking/cycle trail between SH6 and the Cardrona River was noted as being poor, and a potential safety hazard. Mayor Boult noted that this item would be discussed with the NZTA at the upcoming Transport Governance Group meeting. - The community noted that the Clutha River jet boat ban has been working well. - A key issue for the community is the Wanaka airport development, specifically the proposed flightpath and number of aircraft daily. -

Kawarau Falls Station by George Singleton

CONTENTS Page 3: Lorenzo Resta and his House, Arrowtown by Dame Elizabeth Hanan Page 8: James and Mary Flint‟s Voyage from Scotland in 1860 – from James‟s diary Page 12: Arrowtown‟s Christmas Tree by Rita L. Teele and Anne Maguire Page 14: Ivy Ritchie – Arrowtown Town Clerk and Community Stalwart by Denise Heckler Page 17: Our Place in the Sun – a history of the Kelvin Peninsula, reviewed by Elizabeth Clarkson. Interview with the author, George Singleton, by Shona Blair Page 19: Background to the 2015 Calendar: January: Harvesting at Lake Hayes by Marion Borrell February: By Coach to Skippers by Danny Knudson March: Kawarau Falls Station by George Singleton April: Oxenbridge Tunnel by David Hay May: Fire in Ballarat Street, Queenstown, 1882 by Kirsty Sharpe June: The Arrowtown Chinese Settlement and Stores by Denise Heckler Page 30: Page Society News: Chairperson‟s Annual Report 2014 Annual Financial Statements Museum Exhibition: WWI & the Wakatipu: Lest We Forget Creating the Exhibition by Angela English A New APProach to Promoting Local History By Marion Borrell (Editor) In the past the Society has promoted our local history through campaigns, submissions, magazines, books, meetings, trips, guided walks, memorials, heritage conservation trusts, tree-planting, signage, plaques, the Queenstown Walking Guide, and our website. We‟re indebted to all the previous committees who used every means at their disposal. Now we have a new device – the smartphone app – by which large numbers of people can receive a lot of information while on the move around the district. We‟re grateful to Anthony Mason for offering us the concept and his time and technical expertise to make it happen, and grateful for the support of the Community Trust of Southland and the Lakes District Museum. -

Queenstown Trails Trust

Kennedy, Mandy QUEENSTOWN TRAILS TRUST Other Comments 6. Would you like to comment on any other aspect of this draft 10 Year Plan? See attached submission KENNEDY, MANDY KENNEDY, // 8 MAY 2015 8 MAY // FULL SUBMISSIONS // 10YP 2015–2025 688 Queenstown Trails Trust - QLDC Annual Grant Submission Thank you for the past support of the Queenstown Trails Trust (QTT) in regard to the annual grant of $50,000. QTT utilises the annual grant to offset the administration costs of the Trust. When the Wakatipu Trails Trust (WTT) was formed in 2004, there was an agreement between QLDC and the WTT (now known as QTT) for support of the Trust in the form of this administration grant. Over the past year a lot has been achieved by the QTT. The support of QLDC with the administration grant assists us greatly to continue to maintain and develop the network of trails within the Wakatipu Basin. QTT is a charity with two part-time employees and a supportive team of volunteers known as Friends of the Trails. Queenstown’s trail network has expanded to become a serious contributor to the destination. The trails network now provides improved commuter linkages, recreation and tourism experiences, business opportunities and adds some new news for marketing and positioning Queenstown in domestic and international markets. QTT has made a considerable contribution in terms of promotion of the trails and to the maintenance/enhancement of the trail network. Over the past twelve months we have delivered the following:- Upgrade of the Gibbston River Trail Network ($385,000 investment) Upgrade of the Kelvin Peninsula Loop ($78,000 investment) Successful in securing funding from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment ‘Maintaining the Quality of Great Rides’ fund to provide funding with the maintained to the Twin Rivers Trail (Old McDonald’s Hill section), Twin Rivers Trail (Upper Kawarau Trail), Glenda Drive to the Wakatipu Gun Club in excess of $250,000.