Grinding Decline in Springfield

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Windsor Locks Main Street Study

TOWNTOWN OFOF WINDSORWINDSOR LOCKS,LOCKS, CONNECTICUTCONNECTICUT © BRAD WELTON AERIAL PHOTOGRAPHY PREPARED BY: DOWNTOWN MASTER PLAN FINAL DRAFT MAY, 2008 IN ASSOCIATION WITH: AMADON & ASSOCIATES, INC Funded in part by a grant from the Connecticut Main Street Center, Inc., and the FUSS & O’NEILL Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism. TABLETABLE OFOF CONTENTSCONTENTS GOALS............................................................................PAGE 2 TRANSPORTATION / PARKING PROCESS……………………………………………………PAGE 3 RECOMMENDATIONS…………………………......….PAGE 29 EXISTING CONDITIONS / OPPORTUNITIES TRANSPORTATION BICYCLE / PEDESTRIAN AND CONSTRAINTS…………………………………........PAGE 4 RECOMMENDATIONS........................………......…..PAGE 32 REGIONAL INFLUENCES………………………………...PAGE 5 TRANSPORTATION RAIL…………………….......….PAGE 33 STUDY AREA……………………………………………….PAGE 6 EXISTING STATION LOCATIONS………...........…...PAGE 34 HISTORIC INFLUENCES……………………...................PAGE 7 MAINTAIN / ENHANCE SENSE OF PLACE………..PAGE 35 WINDSOR LOCKS TODAY…………………...................PAGE 8 STREETSCAPE RECOMMENDATIONS………...….PAGE 36 MARKET ASSESSMENT………………………………….PAGE 9 KEY REDEVELOPMENT PARCELS….....................PAGE 39 EXISTING LAND USE………………………………….....PAGE 12 KEY DEVELOPMENT PARCEL………………..…….PAGE 41 EXISTING ZONING………………………………………..PAGE 13 “Historic Train Station” EXISTING RECREATIONAL AND KEY DEVELOPMENT PARCEL…………..………….PAGE 45 ENVIRONMENTAL…………………….......................….PAGE 14 “Montgomery Mill” EXISTING TRANSPORTATION………………………….PAGE 15 KEY DEVELOPMENT PARCEL……………….….…..PAGE -

Narrative Report

䤀ⴀ㠀㤀 䰀攀戀愀渀漀渀Ⰰ 一䠀 ⴀ 䠀愀爀琀昀漀爀搀Ⰰ 嘀吀 䈀爀椀搀最攀 刀攀挀漀渀猀琀爀甀挀琀椀漀渀 ☀ 圀 椀搀攀渀椀渀最 倀爀漀樀攀挀琀 吀䤀䜀䔀刀 㤀 ⴀ 䜀爀愀渀琀 䄀瀀瀀氀椀挀愀琀椀漀渀 U.S. Department of Transportation Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery ”TIGER” GRANT APPLICATION PROJECT NARRATIVE REPORT Project Name: I-89 Lebanon, NH – Hartford, VT Bridge Reconstruction and Widening Project Project Type: Bridge Rehabilitation Project Location: Urban, Lebanon, NH and Hartford, VT Project Website: https://www.nh.gov/dot/projects/lebhart16148/index.htm Funds Requested: $10,000,000 (28%) Other State and Federal Funds New Hampshire: $17,056,000 (48%) Vermont: $ 8,544,000 (24%) Total Construction Costs: $35,600,000 Contact: Mr. L. Robert Landry, Jr., P.E. Administrator, Bureau of Bridge Design New Hampshire Department of Transportation 7 Hazen Drive, PO Box 483 Concord, NH 03302-0483 Telephone: 603.271.3921 [email protected] DUNS #: 80-859-1697 Vietnam Veterans Memorial Bridges Interstate 89 Lebanon, NH – Hartford, VT 1 Table of Contents OVERVIEW AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 3 PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................................................. 5 TRANSPORTATION CHALLENGES THE PROJECT AIMS TO ADDRESS ........................................................... 7 HOW THE PROJECT WILL ADDRESS THESE CHALLENGES ............................................................................ 7 PROJECT PARTIES ........................................................................................................................................ -

Preserving Connecticut's Bridges Report Appendix

Preserving Connecticut's Bridges Report Appendix - September 2018 Year Open/Posted/Cl Rank Town Facility Carried Features Intersected Location Lanes ADT Deck Superstructure Substructure Built osed Hartford County Ranked by Lowest Score 1 Bloomfield ROUTE 189 WASH BROOK 0.4 MILE NORTH OF RTE 178 1916 2 9,800 Open 6 2 7 2 South Windsor MAIN STREET PODUNK RIVER 0.5 MILES SOUTH OF I-291 1907 2 1,510 Posted 5 3 6 3 Bloomfield ROUTE 178 BEAMAN BROOK 1.2 MI EAST OF ROUTE 189 1915 2 12,000 Open 6 3 7 4 Bristol MELLEN STREET PEQUABUCK RIVER 300 FT SOUTH OF ROUTE 72 1956 2 2,920 Open 3 6 7 5 Southington SPRING STREET QUINNIPIAC RIVER 0.6 MI W. OF ROUTE 10 1960 2 3,866 Open 3 7 6 6 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 MARKET STREET & I-91 NB EAST END I-91 & I-84 INT 1961 4 125,700 Open 5 4 4 7 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 EB AMTRAK;LOCAL RDS;PARKING EASTBOUND 1965 3 66,450 Open 6 4 4 8 Hartford INTERSTATE-91 NB PARK RIVER & CSO RR AT EXIT 29A 1964 2 48,200 Open 5 4 4 9 New Britain SR 555 (WEST MAIN PAN AM SOUTHERN RAILROAD 0.4 MILE EAST OF RTE 372 1930 3 10,600 Open 4 5 4 10 West Hartford NORTH MAIN STREET WEST BRANCH TROUT BROOK 0.3 MILE NORTH OF FERN ST 1901 4 10,280 Open N 4 4 11 Manchester HARTFORD ROAD SOUTH FORK HOCKANUM RIV 2000 FT EAST OF SR 502 1875 2 5,610 Open N 4 4 12 Avon OLD FARMS ROAD FARMINGTON RIVER 500 FEET WEST OF ROUTE 10 1950 2 4,999 Open 4 4 6 13 Marlborough JONES HOLLOW ROAD BLACKLEDGE RIVER 3.6 MILES NORTH OF RTE 66 1929 2 1,255 Open 5 4 4 14 Enfield SOUTH RIVER STREET FRESHWATER BROOK 50 FT N OF ASNUNTUCK ST 1920 2 1,016 Open 5 4 4 15 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 EB BROAD ST, I-84 RAMP 191 1.17 MI S OF JCT US 44 WB 1966 3 71,450 Open 6 4 5 16 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 EAST NEW PARK AV,AMTRAK,SR504 NEW PARK AV,AMTRAK,SR504 1967 3 69,000 Open 6 4 5 17 Hartford INTERSTATE-84 WB AMTRAK;LOCAL RDS;PARKING .82 MI N OF JCT SR 504 SB 1965 4 66,150 Open 6 4 5 18 Hartford I-91 SB & TR 835 CONNECTICUT SOUTHERN RR AT EXIT 29A 1958 5 46,450 Open 6 5 4 19 Hartford SR 530 -AIRPORT RD ROUTE 15 422 FT E OF I-91 1964 5 27,200 Open 5 6 4 20 Bristol MEMORIAL BLVD. -

The Silting of Lake Springfield

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION NO. 16 1952 STATE OF ILLINOIS ADLAI E. STEVENSON. Governor THE SILTING OF LAKE SPRINGFIELD SPRINGFIELD, ILLINOIS J. B. Stall. L. C. Goffschalk, and H. M. Smith A Co-operative Study by the Illinois State Water Survey Division and the United States Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service with local aid from the City of Springfield Water, Light and Power Department DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION C. HOBART ENGLE, Director STATE WATER SURVEY DIVISION A. M. BUSWELL, Chief (Printed by authority of the State of Illinois) CONTENTS Page Summary iii Introduction 1 Scope of Investigations 1 Acknowledgment 2 RESERVOIR General Information 3 Methods of Survey 3 Sedimentation in the Reservoir 6 Summary of Data 6 Typical Cross-Sections 6 Comparison to Other Illinois Reservoirs 8 Remaining Useful Life of the Reservoir 9 Hydrologic Design 9 Reservoir Operation and Need 10 Analysis of Future Water Supply Needs 10 Date Water Shortage May Occur 10 Financial Aspects 11 WATERSHED Physiography 11 Soils, Land Use and Slopes 12 Erosion 15 Sources of Sediment 16 REMEDIAL MEASURES Control of Sediment 16 Land Treatment Measures 16 Desilting Basins 18 Costs and Benefits of Conservation 18 Development of a Watershed Treatment Plan 18 Need 18 Elements and Orientation 19 Available Aids 19 Methods of Application 20 Cooperative Project 20 Purchase of Critical Erosion Areas 21 Recommendations 21 SUMMARY 1. Lake Springfield, the municipal water only 19.7 percent of the drainage area. An addi• supply reservoir at Springfield, Illinois was tional 33 percent of the sheet erosion occurs on completed in 1934 at a cost of about $2,500,000. -

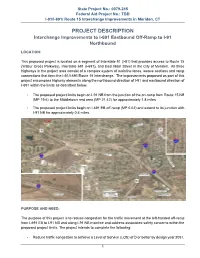

PROJECT DESCRIPTION Interchange Improvements to I-691 Eastbound Off-Ramp to I-91 Northbound

State Project No.: 0079-245 Federal Aid Project No.: TBD I-91/I-691/ Route 15 Interchange Improvements in Meriden, CT PROJECT DESCRIPTION Interchange Improvements to I-691 Eastbound Off-Ramp to I-91 Northbound LOCATION: This proposed project is located on a segment of Interstate 91 (I-91) that provides access to Route 15 (Wilbur Cross Parkway), Interstate 691 (I-691), and East Main Street in the City of Meriden. All three highways in the project area consist of a complex system of mainline lanes, weave sections and ramp connections that form the I-91/I-691/Route 15 Interchange. The improvements proposed as part of this project encompass highway elements along the northbound direction of I-91 and eastbound direction of I-691 within the limits as described below. • The proposed project limits begin on I-91 NB from the junction of the on-ramp from Route 15 NB (MP 19.6) to the Middletown rest area (MP 21.42) for approximately 1.8 miles. • The proposed project limits begin on I-691 EB off-ramp (MP 0.02) and extend to its junction with I-91 NB for approximately 0.4 miles. PURPOSE AND NEED: The purpose of this project is to reduce congestion for the traffic movement at the left-handed off-ramp from I-691 EB to I-91 NB and along I-91 NB mainline and address associated safety concerns within the proposed project limits. The project intends to complete the following: • Reduce traffic congestion to achieve a Level of Service (LOS) of D or better by design year 2051. -

Economic Development 2017-18 Business Profile

Economic Development 2017-18 Business Profile Rocky Hill Connecticut. Family Focused with a Corporate Presence… ROCKY HILL, CT. From corporate office parks to Dinosaur State Park and historic Ferry Park along the CT River, Rocky Hill continues to accommodate growth Rocky Hill is a suburban community of 21,000 residents located in central Connecticut two hours from both Boston and New York City. Access is and community reinvestment without provided directly from Interstate 91 while Bradley International Airport is sacrificing our small town a twenty minute drive. Our location within Connecticut and within New atmosphere. Through prudent England places Rocky Hill businesses within 500 miles to 1/3 of the U.S. management, we maintain a low tax economy and 2/3 of the Canadian economy. rate and a commitment to business while maintaining an exemplary Rocky Hill is home to 1300 business establishments employing over 18,000 people. Our substantial employment base consists of diverse industries education system and a high quality and service establishments such as Henkel North America, Arburg, SYSCO, of life. URS Corporation, Burris Refrigerated Logistics, AECOM, Simoniz USA, PDQ Inc., The Meredith Corporation, McKesson, Paychex, Regus, Walmart and Sheraton, among many others. All of our businesses are located within our six business parks and two commercial corridors. Rocky Hill is primarily A market analysis projected an additional 1.8 million square feet of new residential with a 33% development is possible by the year 2030. It is anticipated 2017-19 will commercial tax base. realize the completion of approximately 252,000 square feet of commercial Residents and businesses construction. -

Interstate 91 Land Port of Entry (LPOE) Project Derby Line, Vermont – Stanstead, Quebec

Interstate 91 Land Port of Entry (LPOE) Project Derby Line, Vermont – Stanstead, Quebec Project Lead U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) Building Occupant U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Estimated Project Cost $23,000,000 Construction Start September 2016 Substantial Completion June 2018 Construction Management Coast and Harbor Associates, Inc., Lynnfield, MA Construction Contractor D.E.W. Construction, Williston, VT VTrans Point of Contact Robert M. White, Right of Way Chief The current facility at the Derby Line Port of Entry was built in 1965 and is undergoing a replacement/refresh which will bring much needed improvements. The following improvements will deliver long-term operational, environmental, public safety and security benefits: Construction of a new commercial inspection facility and primary cargo processing lanes Prioritization of officer and public safety, including increased site security Construction of new passenger vehicle inspection booths and associated canopies Improved traffic flow to, from and within the Derby Line Port Building of new Trusted Traveler Enrollment Center with dedicated access for the public Construction of new passenger processing areas and vehicle inspection bays Segregated and dedicated commercial bus approach lane These improvements will reduce cross-border travel times, improve the traveler experience while providing a modern, environmentally responsible, and welcoming facility. The project is being constructed in two phases with the site being split by I91 and phase one consisting of the western half improvements and phase two being the eastern half. Phase one is complete and phase two is anticipated to be complete by August 2018. There has been continuous coordination between all stakeholders including our Providence of Quebec counterparts. -

W I N D S O R • C O N N E C T I C

WINDSOR • CONNECTICUT FOR LEASE PROPERTY OVERVIEW CBRE is pleased to offer for lease ±142,000 SF of Class A, headquarters-style office space at 200 Great Pond Drive in Windsor, Connecticut. Formerly occupied by GE/Alstom Power, 200 Great Pond Drive is available in its entirety and features twin east and west wings, each with their own entrance, two-story atrium lobby, restrooms and elevators. Existing build-out is configured for single-tenant occupancy but can be easily subdivided for multi-tenancy, with each floor measuring± 47,000 SF. 200 Great Pond Drive offers amenities including a full-service cafeteria, outdoor patio/ courtyard, secure key-card access and above- standard parking. Situated within the Day Hill Corporate Area of Windsor, the building also enjoys a professional, corporate campus office setting with immediate access and visibility from Day Hill Road. This excellent north market location puts 200 Great Pond Drive within minutes of Bradley International Airport, four HIGHLIGHTS area hotels and numerous corporate neighbors including CIGNA, ISO New England, The • Signature, Class A office property situated along Hartford, Travelers, Veritiv, Voya and more. a prominent office corridor • Ideal corporate headquarters’ owner occupant opportunity • Largest freestanding availability in suburban Greater Hartford • Convenient north market location with easy access to Interstate 91 at Exit 38 and just minutes to Bradley International Airport • Strong nearby amenities include four hotels • Matching east/west lobbies allow for easy -

Directions to Upper Valley Towns' Gyms for Basketball Games

Directions to Upper Valley Towns' Gyms for Basketball Games CCBA Witherell Center – 1 Campbell Street, Lebanon NH 03766 From the North: I-89 south to Exit 18 (DHMC/Lebanon High School). Bear right off the exit and continue on Route 120 to stop sign. Turn left onto Hanover St. Follow Hanover St. for approximately 1/2 mile and take a left into the parking lot next to Village Pizza/Peking Tokyo/Lebanon Floral mini-mall. Stay to the left and go down a slight hill bearing to the right at the bottom of the hill. Continue around the municipal parking lot onto Taylor St. The Witherell Center will be on you left. From the South: I-89 to Exit 17 (Enfield/Lebanon).Take a left off the exit and follow Route 4 into downtown Lebanon. Approx. 3 miles. At the green take your first right onto Campbell St. Turn right at the end of Campbell St. onto Parkhurst St. Take your first left onto Spencer St., go approx. 100 yards and drive straight into the Witherell Center's parking lot. HANOVER Richmond Middle School Gym - 63 Lyme Rd, Hanover NH 03755 From Interstate 89: Take Exit 18 in New Hampshire and follow Route 120 north for about 6 miles into Hanover. At the traffic light adjacent to the Mobil Station go straight (this is now called Park Street) and continue through two additional traffic lights. At the third light, bear right and follow Rt. 10 north for 1.4 miles. (A landmark to look for is the Police/Fire Station on your left just beyond Reservoir Road. -

One Financial Plaza at 1350 Main Street

ONE FINANCIAL PLAZA AT 1350 MAIN STREET Class A Office Space Available for Lease in Downtown Springfield 1350 Main Street | Springfield, MA 01103 1350MainStreet.com • 17-story, 330,000 SF Class A office tower. Smaller offices to 19,195 SF full floors available with reception, conference room, and corner offices. • 5 High Speed Elevators. • Palazzo Café, gourmet coffee and sandwich shop on the first floor. • New State-of-the-Art Fitness Center at 180 Fit located on the 9th floor • Prime access and visibility for tenants and visitors with all the amenities of downtown Springfield within steps including parking, restaurants, the Mass Mutual Center & City Hall. • Park-like setting with outdoor seating. • Amazing views of the City and the Connecticut River. • Brand New Riverfront Park located in close proximity with walking and bike trails. • Easy highway access, I-91 off ramp one block away. • Only 30 minutes north of Hartford and within minutes of Bradley International Airport. • 24/7 Security/Concierge-style service and Onsite Management. • Convenient parking only one block away with public transportation in front of the building. Located in the Heart of Downtown Springfield Main Street Entrance & Court Street Entrance Offering 372 SF to Full Floors of 19,195 SF Park-like Setting/ With Outdoor Seating Palazzo Café on the First Floor & 180Fit Gym on the 9th Floor Civic Center Garage One Block to Civic Center Garage Civic Center Garage Amazing Views of the City & Connecticut River Within Walking Distance to the New Riverfront Park & Walking/ -

History of Rocky Hill: 1650 - 2018 Robert Campbell Herron October 2017

History of Rocky Hill: 1650 - 2018 Robert Campbell Herron October 2017 Bring Us Your History ........................................................................................................ 4 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. 4 Origins: 250,000,000 BCE to 1730 CE .............................................................................. 4 Dinosaurs ........................................................................................................................ 4 Pre-European History...................................................................................................... 5 The Europeans Arrive ..................................................................................................... 5 The Settlement of the Town ............................................................................................ 6 Maritime Rocky Hill ........................................................................................................... 6 The Ferry ......................................................................................................................... 7 The River and Seafaring ................................................................................................. 7 Rocky Hill and Slavery ..................................................................................................... 10 Slaves in Rocky Hill .................................................................................................... -

I-291 Logistics Center South

I-291 LOGISTICS FOR LEASE CENTER SOUTH 240 Ellington Road, South Windsor, CT 06095 182,000 SF Warehouse/Office Building *Photo is of a recently completed project by Scannell that 240 Ellington Road is expected to resemble www.cbre.us/hartford *Photo is of a recently completed project by Scannell that 240 Ellington Road is expected to resemble UP TO 182,000 SF AVAILABLE CBRE is pleased to present a unique opportunity to lease 182,000 SF of Class A warehouse space and join the other tenants in Connecticut’s newest logistics center in South Windsor, Connecticut. This prime central Connecticut location is less than a half mile to Exit 4 on Interstate 291, offers tremendous visibility from Interstate 291 and is under three miles to both Interstate 91 and 84 two of Connecticut’s primary interstates. This Logistics Center is strategically located approximately halfway between New York City and Boston. PROPERTY FEATURES + Total Building Size: 182,000 SF + Lighting: BTS + Available: 182,000 SF + Parking: 130 auto; TBD trailer + Land Area: 15 acres + Power: 3,000 A + Clear Height: 32’ + HVAC: Rooftop gas and makeup air units (can be higher or lower as needed) + Zoning: Industrial + Column Spacing: + Floor Slab: 6’’ 50’ x 50’ – + Utilities: – 50’ x 60’ at dock doors – Water/Sewer: MDC + Loading: 40 dock doors, two drive-in doors – Gas: Yankee Gas + Sprinkler: ESFR – Electric: Eversource SITE PLANELEVATIONS AREA DEMOGRAPHICS POPULATION • Green Bay Population: 104,796 • Brown County Population: 262,052 COUNTY WORKFORCE • Brown County: 69.3% of individuals