Bhardwaj Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b9h1rs Author Sriram, Pallavi Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Pallavi Sriram 2017 Copyright by Pallavi Sriram 2017 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel by Pallavi Sriram Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Janet M. O’Shea, Chair This dissertation presents a critical examination of dance and multiple movements across the Coromandel in a pivotal period: the long eighteenth century. On the eve of British colonialism, this period was one of profound political and economic shifts; new princely states and ruling elite defined themselves in the wake of Mughal expansion and decline, weakening Nayak states in the south, the emergence of several European trading companies as political stakeholders and a series of fiscal crises. In the midst of this rapidly changing landscape, new performance paradigms emerged defined by hybrid repertoires, focus on structure and contingent relationships to space and place – giving rise to what we understand today as classical south Indian dance. Far from stable or isolated tradition fixed in space and place, I argue that dance as choreographic ii practice, theorization and representation were central to the negotiation of changing geopolitics, urban milieus and individual mobility. -

Bharatanatyam: Eroticism, Devotion, and a Return to Tradition

BHARATANATYAM: EROTICISM, DEVOTION, AND A RETURN TO TRADITION A THESIS Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Religion In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Taylor Steine May/2016 Page 1! of 34! Abstract The classical Indian dance style of Bharatanatyam evolved out of the sadir dance of the devadāsīs. Through the colonial period, the dance style underwent major changes and continues to evolve today. This paper aims to examine the elements of eroticism and devotion within both the sadir dance style and the contemporary Bharatanatyam. The erotic is viewed as a religious path to devotion and salvation in the Hindu religion and I will analyze why this eroticism is seen as religious and what makes it so vital to understanding and connecting with the divine, especially through the embodied practices of religious dance. Introduction Bharatanatyam is an Indian dance style that evolved from the sadir dance of devadāsīs. Sadir has been popular since roughly the 6th century. The original sadir dance form most likely originated in the area of Tamil Nadu in southern India and was used in part for temple rituals. Because of this connection to the ancient sadir dance, Bharatanatyam has historic traditional value. It began as a dance style performed in temples as ritual devotion to the gods. This original form of the style performed by the devadāsīs was inherently religious, as devadāsīs were women employed by the temple specifically to perform religious texts for the deities and for devotees. Because some sadir pieces were dances based on poems about kings and not deities, secularism does have a place in the dance form. -

CBSE NET Performing-Art December-2013 Solved Paper III Download All the Papers to Prepare for NET 2021

9/17/2021 CBSE NET Performing-Art December 2013 Solved Paper III Download All the Papers to Prepare for NET 2021- Examrace Examrace Paper 3 has been removed from NET from 2018 (Notification)- now paper 2 and 3 syllabus is included in paper 2. Practice both paper 2 and 3 from past papers. CBSE NET Performing-Art December-2013 Solved Paper III Download All the Papers to Prepare for NET 2021 Online Paper 1 complete video course with Dr. Manishika Jain. Lifetime subscription. Includes tests and expected questions. Join now! 1. Select the correct sequence from the following as per Natyashastra (A) Rasa, Tandava Lakshmana, Nandi, Nayaka Bheda (B) Tandava Lakshmana, Rasa, Nandi, Nayaka Bheda (C) Nandi, Tandava Lakshmana, Rasa, Nayaka Bheda (D) Nandi, Rasa, Nayaka Bheda, Tandava Lakshmana Answer: C 2. The “Nandi” of Natyashastra can be called (A) “Avanu” of Bhavai (B) Preliminary of a Play (C) Purvaranga of Dance (D) All of above Answer: D 3. Assertion (A) : The nature and degree of transformation from martial trait to stylised and aesthetic has great range. Reason (R) : Indian theatrical styles favour martial arts. Codes: (A) Both (A) and (R) true. (B) Both (A) and (R) false. (C) (A) true (R) false. (D) (A) false (R) true. Answer: C 4. Pick the odd one out: 1 of 9/17/2021 CBSE NET Performing-Art December 2013 Solved Paper III Download All the Papers to Prepare for NET 2021- Examrace (A) Gangavataran (B) Talapushpaputa (C) Udhvahita (D) Bhujangatrasit Answer: C 5. Match the following: List – I List – II List I a. -

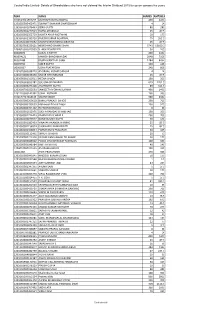

ADF Foods IEPF Website

ADF Foods Limited Statement of Unclaimed dividend amount consecutively for 7 years, whose shares are to be transferred to the Demat Account of IEPF Authority as on 31.10.2017 Sr no Folio no Name Base Holding Current Holding IEPF Physical Holding 1 1201090000812250 STEVEN AUGUSTINE ALEXANDER 10 10 10 2 1201090000873516 BHANWARI DEVI KHICHA 100 100 100 3 1201700000009940 PREM CHAND ARORA 100 100 100 4 1203320001050910 DHARMENDRASINH J ZALA 100 100 100 5 1302590000175270 PRABHA SOOD 100 100 100 6 1303930000001410 JYOTI RANI . 200 200 200 7 A000115 ADITYA NARAIN 100 100 100 8 A000116 ADITYA NATARAJAN 500 500 500 9 A000117 AJAY B SHAH 100 100 100 10 A000123 AJAYKUMAR CHANDULAL SONI 100 100 100 11 A000132 ALIMOHAAMED ABDULLA 100 100 100 12 A000138 ALPESH S BHANUSHALI 100 100 100 13 A000153 ANANTRAO BAJIRAO LUNDGE 100 100 100 14 A000177 ANJALI KRISHNAN 100 100 100 15 A000187 AFTAB ANWAR KHAN 500 500 500 16 A000204 MALHOTRA DEEPAK 200 200 200 17 A000208 ASHA RAGHUVEER KOTIAN 300 300 300 18 A000213 ASHISH NAROTTAMDAS MAJITHIA 100 100 100 19 A000220 ASHOK JANARDHAN SALIAN 300 300 300 20 A000224 ASHOK RUPAREL 100 100 100 21 A000225 ASHOK S KHATOR 300 300 300 22 A000226 ASHOK VADILAL SHAH 100 100 100 23 A000229 ASHWIN J GORADIA 100 100 100 24 A000239 AVNI PRANJIVAN GALA 100 100 100 25 A000537 R SURYANARAYAN 100 100 100 26 A000539 ANITA PAREKH 500 500 500 27 A000542 AYUB KHAN 200 200 200 28 A000564 ARFANA AHMED KISHAN 500 500 500 29 A001064 ABDUL LATEEF SHAIKH 100 100 100 30 A001067 ALOK CHADHA 100 100 100 31 A001096 ATUL U SHAH 100 100 100 32 A001114 -

Innovations in Contemporary Indian Dance: from Religious and Mythological Roots in Classical Bharatanatyam Ketu H

Religion Compass 7/2 (2013): 47–58, 10.1111/rec3.12030 Innovations in Contemporary Indian Dance: From Religious and Mythological Roots in Classical Bharatanatyam Ketu H. Katrak* University of California, Irvine Abstract Contemporary Indian Dance as a new multi-layered dance genre unfolds at the intersection of Indian classical dance and other movement vocabularies such as modern dance, yoga, martial arts, and theatre techniques. This three-part essay traces a brief history of the ‘‘revival’’ of bharatanat- yam in late 19th and early 20th century, then discusses the work of pioneers in Contemporary Indian Dance, Chandralekha, Anita Ratnam, and Hari Krishnan. Discussion includes a redefinition of the sacred, use of Indian goddesses and epic stories for contemporary relevance, as well as the subverting of stereotypes of gender, culture, and nation in Contemporary Indian Dance. Expressive arts such as music and dance in the Hindu tradition constitute integral parts of ritual worship and daily devotional practices for many worshippers in India. In particular, the history of temple dance performed by devadasis or temple dancers (discussed below) provides significant antecedents for Contemporary Indian Dance, a new multi-layered and hybrid genre used increasingly since the 1980s in India and the diaspora (with early 20th century pioneer Uday Shankar (Chakravorty & Khokar 1984)). This new style is rooted mainly in two of the eight classical Indian dance styles, bharatanatym and kathak.1 This essay presents an innovative intervention in Religious Studies via my analysis of selected Contemporary Indian dancers’ choreography and their reinterpretations of tradi- tional Indian religious and mythological stories. Further, my critical analysis of these artists’ contemporary choreography using abstract movement versus narrative, deploying the body as a sacred space brings illuminations to scholars of Religion. -

Banis / बानी and Schools Are Aplenty

PAPER: 3 Detail Study Of Bharatanatyam, Devadasis-Natuvnar, Nritya And Nritta, Different Bani-s, Present Status, Institutions, Artists Module 18 Institutions Of Bharatanatyam Present day Bharatanatyam banis / बानी and schools are aplenty. There are many branches of main banis and some as far as in New Jersey in USA or Ukhrul in Manipur! Since Bharatanatyam has spread far and wide, each dancer is adding something to what was learnt and trying to extend its boundaries and body. Many dancers are also teachers today, so they are adding new poses or postures and calling it sub banis or schools. Schools today mean individual teaching establishments, not a generic bani or style. It means in one city itself, say small town like Mysore or Baroda, there could be ten schools of Bharatanatyam. Each teaching same dance, differently. In that, there is no standardization. In one area of a big metro like Chennai or Bangalore, Mylapore or Malleswaram, there are over a dozen teachers teaching from same bani differently. This is not to break away as much as what one learnt from a guru and how much. Schools of Bharatanatyam today within one city can be in hundreds, especially nerve centre of dance like Chennai. The Dhananjayans, Chandrasekhars, Ambika Buch, Savitri Jagannath Rao, M.V. 1 Narasimhachari and Vasanthalakshmi, Sheejith Krishna, P.T. Narendran, Shijith Nambiar and Parvathy Menon teach the Kalakshetra style. J. Suryanarayanamurthy, a disciple of the Dhananjayans, is a popular teacher. Sreelatha Vinod, Tulsi Badrinath, Radhika Surajit, Shobana Bhalchandra are ardent disciples of the Dhananjayans and faithfully follow their teachers’ teachings. -

CID Virtual Library of the Dance at

CID permanent program No. 4 CID Virtual Library of the Dance at www.CID-portal.org/virtual-library/ Books and magazines authored or edited by members of the International Dance Council CID at UNESCO. The list is posted at the CID Portal and circulated world-wide. This results in : 1. Prestige, as the public realizes the enormous intellectual production of CID Members: more than 650 books and over 40 magazines. 2. More sales, since no publisher can have the wide contacts CID has within the dance world. 3. Lower cost, as readers can order books directly to publishers or to authors. 4. Feedback, since authors can receive comments from their readers. 5. Better acquaintance between CID members, once they know the research interests and publication achievements of each other. Books authored or edited by Members of CID www.CID-portal.org/virtual-library/ Updated: 06 May 2019 - A - Aelita Kondratova (ed.): Proceedings of the 36th World Congress on Dance Research, Saint Petersburg, 2013. Saint Petersburg, 2015. Aelita Kondratova(ed.): Proceedings of the 39th World Congress on Dance Research. Saint Petersburg, Saint Petersburg Section CID, 2015, 184 p. Aelita Kondratova (ed.): Proceedings of the 47th World Congress on Dance Research. Saint Petersburg, Saint Petersburg Section CID, 2016, 222 p. Aja Jung (ed.): Decadance. Ten years of Belgrade Dance Festival. Beograd, 2013, 143 p. Alba G.A. Naccari: Pedagogia della corporeità. Educazione, attività motoria e sport nel tempo. Perugia, Italy, Morlacchi, 2003, 297 p. Alba G.A. Naccari: Le vie della danza. Pedagogia narrativa, danze etniche e danzamovimentoterapia. Perugia, Italy, Morlacchi, 2004, 295 p. -

A Musical Fair

- J 2 . T was no different from other music MUSIC FESTIVAL people realised the benefits of punc festivals that Bombay is treated to tuality.” It was decided that those who during the peak music season, except I came first would get the better seats in that it was organised by Protima Bedi, A their block. “I wanted to train the and her Odissi Dance Centre students. audience to be on time,” explains Pro And since Protima is a commercial Musical tima. Unfortunately, the earliest arriv- password when it comes to all things ers took to the first few rows, which cultural, the festival drew to its had been reserved for VIPs—like V.P. charmed circle, big names. As a result, Fair Sathe, Minister of Information & contrary to a few thousand rupees that Broadcasting, Frank Simoes, who in a more modest organisation would cidentally took a load off the organis collect on such an occasion, Protima’s ers’ shoulders by collecting all the rough estimate stood at Rs 2 lakh. “We advertisements for the brochure and had aimed at about Rs 5 lakh. Let’s surprisingly enough, Kabir Bedi. Bedi, see—maybe some more contributions who sat in the third row, was easily one will come in,” says a disappointed head taller than the rest of the audience Protima. forcing the luckless spectators behind The proceeds are to go towards the him to crane their necks. At the end Odissi Dance Centre, initiated two everyone had been seated to his years ago to “celebrate, preserve and satisfaction and the session was 45 perpetuate” Odissi, which as a dance minutes behind schedule. -

Unclaimed Intdiv13 Website.Pdf

FLNO NAM1 SHARES AMT2013 IN30023911567299 MUTHAPPAN RAJAGOPAL 400 1400 1201060000462471 SUMANT SHANKAR DHARESHWAR 4 14 1201060001076463 RENU GUPTA 80 280 1201060002277519 ISMAIL ZHABIULLA 25 87.5 1201060002352750 MUKTA ANUP MOTWANI 50 175 1201060002395710 RAJESH KUMAR AGARWAL 75 262.5 1201060100195562 MOHAN KESHAWRAO DEOTALE 25 87.5 1203320003229121 NEMCHAND SHAMJI SHAH 3743 13100.5 1204010000013555 V. AKHILESH REDDY . 30 105 K0006892 KUNAL K MEHTA 400 1400 M0004121 MANISH BHAGAWANDAS 2048 7168 R0002488 RAJANI KANTILAL SHAH 1284 4494 S0003784 SUBIR GUPTA 128 448 U0000367 UDAY PRATAPSINH 248 868 1201070000038720 ANURAAG KUMAR SANGHI 4 14 1201070000198190 SAGAR HARI NEMADE 25 87.5 1201090001310515 NEENA SIMON 100 350 1201090003653181 SUGUNA SRIDHARAN 629 2201.5 1201090005243206 AMARNATH GUTTA 89 311.5 1201090700022603 SANGEETA MOHAN SURANA 400 1400 1201120000141961 USHA . KOTHARI 100 350 IN30177414018133 SAMAR SINGH 960 3360 1201060000260618 BIMAL PRAKASH SAHOO 200 700 1201060000293059 Mahaveer Prasad Nagar 150 525 1201060000704202 RAYMOND DSOUZA 8 28 1201060001622976 SUDHA RAMDAS SHANBHAG 100 350 1201060001714423 RAJANI DEVI CHAWLA 200 700 1201060100079577 NAND KUMAR GUPTA 40 140 1201060001082403 VINAYAK ANANDA AHIRRAO 25 87.5 1201060002158974 GAJANAN D RAMANKATTI 25 87.5 1201060002306834 PARSOTAM N PRAJAPATI 30 105 1201060100122461 SMRUTI SHASTRI 20 70 1201090000222328 DEEPAK PANDURANG TELAVANE 50 175 1201090000686502 POOJA CHANDRAKANT MAHAJAN 100 350 1201090003048784 KANTTA MITTAL 40 140 1204010000011655 ANUPAMA REDDY . 100 350 J0001060 -

Cover Feature: Buddhist Dances of Bhutan

ISSN 2455-7250 Vol. XVII No. 1 January - March 2017 A Quarterly Journal of Indian Dance Cover Feature: Buddhist Dances of Bhutan A Quarterly Journal of Indian Dance Volume: XVII, No. 1 January-March 2017 Sahrdaya Arts Trust Hyderabad RNI No. APENG2001/04294 ISSN 2455-7250 Nartanam, founded by Kuchipudi Kala Kendra, Founders Mumbai, now owned and published by Sahrdaya G. M. Sarma Arts Trust, Hyderabad, is a quarterly which provides a forum for scholarly dialogue on a broad M. Nagabhushana Sarma range of topics concerning Indian dance. Its concerns are theoretical as well as performative. Chief Editor Textual studies, dance criticism, intellectual and Madhavi Puranam interpretative history of Indian dance traditions are its focus. It publishes performance reviews Patron and covers all major events in the field of dance in Edward R. Oakley India and notes and comments on dance studies and performances abroad. Chief Executive The opinions expressed in the articles and the Vikas Nagrare reviews are the writers’ own and do not reflect the opinions of the editorial committee. The editors and publishers of Nartanam do their best to Advisory Board verify the information published but do not take Anuradha Jonnalagadda (Scholar, Kuchipudi dancer) responsibility for the absolute accuracy of the Avinash Pasricha (Former Photo Editor, SPAN) information. C.V. Chandrasekhar (Bharatanatyam Guru, Padma Bhushan) Cover Photo: A Buddhist Monk, dancing Kedar Mishra (Poet, Scholar, Critic) Kiran Seth (Padma Shri; Founder, SPIC MACAY) Photo Courtesy: Brochure of K. K. Gopalakrishnan (Critic, Scholar) Thimphu Tshechu by Bhutan Leela Venkataraman (Critic, Scholar, SNA Awardee) Communications Services, Mallika Kandali (Sattriya dancer, Scholar) [email protected] Pappu Venugopala Rao (Scholar, Former Associate D G, American Institute; Secretary, Music Academy) Photographers: Kezang Namgay, Reginald Massey (Poet, FRSA & Freeman of London) Leon Rabten, Lakey Dorji, and Sunil Kothari (Scholar, Padma Shri & SNA Awardee) Lhendup for Bhutan Communications Suresh K. -

Published by the Religion and Theatre Focus Group of the Association for Theatre in Higher Education ISSN 1544-8762

http://www.rtjournal.org Published by the Religion and Theatre Focus Group of the Association for Theatre in Higher Education The Journal of Religion and Theatre is a peer-reviewed online journal. The journal aims to provide descriptive and analytical articles examining the spirituality of world cultures in all disciplines of the theatre, performance studies in sacred rituals of all cultures, themes of transcendence in text, on stage, in theatre history, the analysis of dramatic literature, and other topics relating to the relationship between religion and theatre. The journal also aims to facilitate the exchange of knowledge throughout the theatrical community concerning the relationship between theatre and religion and as an academic research resource for the benefit of all interested scholars and artists. ISSN 1544-8762 All rights reserved. Each author retains the copyright of his or her article. Acquiring an article in this pdf format may be used for research and teaching purposes only. No other type of reproduction by any process or technique may be made without the formal, written consent of the author. Submission Guidelines • Submit your article in Microsoft Word 1998 format via the internet • Include a separate title page with the title of the article, your name, address, e-mail address, and phone number, with a 70 to 100 word abstract and a 25 to 50 word biography • Do not type your name on any page of the article • MLA style endnotes -- Appendix A.1. (Do not use parenthetical references in the body of the paper/ list of works cited.) • E-Mail the article and title page via an attachment in Microsoft Word 1998 to Debra Bruch: dlbruch -at- mtu.edu.