Trip to London

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clothing of Kansas Women, 1854-1870

CLOTHING OF KANSAS WOMEN 1854 - 1870 by BARBARA M. FARGO B. A., Washburn University, 1956 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Clothing, Textiles and Interior Design KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1969 )ved by Major Professor ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express sincere appreciation to her adviser, Dr. Jessie A. Warden, for her assistance and guidance during the writing of this thesis. Grateful acknowledgment also is expressed to Dr. Dorothy Harrison and Mrs. Helen Brockman, members of the thesis committee. The author is indebted to the staff of the Kansas State Historical Society for their assistance. TABLE OP CONTENTS PAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENT ii INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURE 1 REVIEW OF LITERATURE 3 CLOTHING OF KANSAS WOMEN 1854 - 1870 12 Wardrobe planning 17 Fabric used and produced in the pioneer homes 18 Style and fashion 21 Full petticoats 22 Bonnets 25 Innovations in acquisition of clothing 31 Laundry procedures 35 Overcoming obstacles to fashion 40 Fashions from 1856 44 Clothing for special occasions 59 Bridal clothes 66 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 72 REFERENCES 74 LIST OF PLATES PLATE PAGE 1. Bloomer dress 15 2. Pioneer woman and child's dress 24 3. Slat bonnet 30 4. Interior of a sod house 33 5. Children's clothing 37 6. A fashionable dress of 1858 42 7. Typical dress of the 1860's 47 8. Black silk dress 50 9. Cape and bonnet worn during the 1860's 53 10. Shawls 55 11. Interior of a home of the late 1860's 58 12. -

DOW 300 Matching Sleeves

www.delongsports.com DOW 300 matching sleeves Adult* 20 - Oxford Nylon 25 - Flight Satin 29 - Poly/Dobby NEW 40 - Cordura Taslan 45 - Poly/Ultra Soft NEW *To order Youth, add a Y at the end of the style number. • Available in outerwear AR fabric options above E • Set-in sleeves match body • Matching or contrasting Insert/lower sleeve • Snap front closure RW standard • Zipper front closure optional, EXTRA • All optional collars available, EXTRA (7, 4, S, UTE N/C) • Collars S, K and W O require Zipper front, EXTRA • Knit 7, 8, K and W collars may contrast with the cuffs and band • Two front welt pockets • All optional linings available, EXTRA. • SIZES: Adult XS-6XL Youth S-XL Note: Regular size is standard. "long" (2" longer in the body and 1" longer in sleeve length) and available at 10% EXTRA "Extra Long" (4" longer in body 2" longer in sleeve.) are available at 20% EXTRA Fabric New Fabric Importance 29 - 100% Polyester high • Breathability in diverse count Dobby with DWR conditions finish, 2A wash test and a • Wind Resistant water resistant breathable • Low water absorption coating. • Water repellency (DWR) New Fabric • Retains durability after 45 - 94% Polyester/ 6% washings (2A Wash) Spandex Ultra Soft face • Color Consistency- with a 4 way stretch. 100% Finishing Process polyester laminated fleece 2012 DELONG CUSTOM 2012 DELONG CUSTOM backing with anti-pilling. DWR finish with 2A wash Teflon/Breathable coating. This all-purpose fabric can be worn year round and with its moisture management characteristic, makes it incredibly durable. page 2 877.820.0916 | fax 800.998.1904 DOW 031 set-in sleeves Adult* • Set-in sleeves match • Knit 7, 8, K and W 20 - Oxford Nylon body or contrast body collars may contrast 25 - Flight Satin • Snap front closure with the cuffs and band 29 - Poly/Dobby NEW standard • Two front welt pockets 40 - Cordura Taslan • Zipper front closure • All optional linings 45 - Poly/Ultra Soft 2012 DELONG CUSTOM NEW optional, EXTRA available, EXTRA. -

![Lljnited States Patent [19] [11] 4,408,355 Hroclr [45] Oct](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2041/lljnited-states-patent-19-11-4-408-355-hroclr-45-oct-682041.webp)

Lljnited States Patent [19] [11] 4,408,355 Hroclr [45] Oct

lljnited States Patent [19] [11] 4,408,355 Hroclr [45] Oct. 11, 1983 [54] HAND WARMEIR 2,727,241 12/1955 Smith ...................................... .. 2/66 2,835,896 5/1958 Giese .... .. 2/66 [76] Inventor: Kenneth Brock, RR. #2, Albion, 3,793,643 2/1974 Kinoshita ................................ .. 2/66 Ind. 46701 Primary Examiner-Doris L. Troutman _ ‘521] AppLNo: 443,061 ' Attorney, Agent, or Firm—K. S. Cornaby [22] Filed: Nov. 19, 1982 [57] ABSTRACT [51] Int. (11.3 ......................... .. ..... .. D0413 7/04 A hand warmer is provided which tightly ?ts against [52] US. Cl. .. 2/66 the waist of the user by means of .an adjustable belt, and [58] Field of Search ............................................ .. 2/ 66 which substantially conforms to the curvature of the [56] References Cited body. An elastic band is disposed in the interior of the muff for holding a heat source device therein, and U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS means are provided at each end opening of the muff for 25,189 2/1896 selectively varying the size thereof between fully open 1,007,922 11/1911 and fully closed. 2,298,600 10/1942 2,351,158 6/1944 6 Claims, 5 Drawing Figures US. Patent -Oct. 11, 1983 4,408,355 4,408,355 1 , 2 ers may be selectively varied between fully open and HAND WARMER I fully closed, and an adjustable belt is attached to the muff to secure it to the body of the user. BACKGROUND OF THE INVENTION This invention pertains to a hand warmer for use in BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE DRAWINGS cold environments, especially for outdoor sportsmen. -

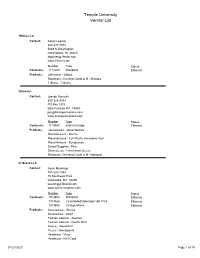

Temple University Vendor List

Temple University Vendor List 19Nine LLC Contact: Aaron Loomer 224-217-7073 5868 N Washington Indianapolis, IN 46220 [email protected] www.19nine.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1112269 Standard Effective Products: Otherwear - Shorts Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Stickers T-Shirts - T-Shirts 3Click Inc Contact: Joseph Domosh 833-325-4253 PO Box 2315 Bala Cynwyd, PA 19004 [email protected] www.3clickpromotions.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1114550 Internal Usage Effective Products: Housewares - Water Bottles Miscellaneous - Koozie Miscellaneous - Cell Phone Accessory Item Miscellaneous - Sunglasses School Supplies - Pen Short sleeve - t-shirt short sleeve Stationary, Greeting Cards & N - Notepad 47 Brand LLC Contact: Kevin Meisinger 781-320-1384 15 Southwest Park Westwood, MA 02090 [email protected] www.twinsenterprise.com Number Type Status Contracts: 1013854 Standard Effective 1013856 Co-branded/Operation Hat Trick Effective 1013855 Vintage Marks Effective Products: Accessories - Gloves Accessories - Scarf Fashion Apparel - Sweater Fashion Apparel - Rugby Shirt Fleece - Sweatshirt Fleece - Sweatpants Headwear - Visor Headwear - Knit Caps 01/21/2020 Page 1 of 79 Headwear - Baseball Cap Mens/Unisex Socks - Socks Otherwear - Shorts Replica Football - Football Jersey Replica Hockey - Hockey Jersey T-Shirts - T-Shirts Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatpants Womens Apparel - Capris Womens Apparel - Womens Sweatshirt Womens Apparel - Dress Womens Apparel - Sweater 4imprint Inc. Contact: Karla Kohlmann 866-624-3694 101 Commerce -

Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines

Chair of Urban Studies and Social Research Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism Bauhaus-University Weimar Fashion in the City and The City in Fashion: Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines Doctoral dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Maria Skivko 10.03.1986 Supervising committee: First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Frank Eckardt, Bauhaus-University, Weimar Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Sonnenburg, Karlshochschule International University, Karlsruhe Thesis Defence: 22.01.2018 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I. Conceptual Approach for Studying Fashion and City: Theoretical Framework ........................ 16 Chapter 1. Fashion in the city ................................................................................................................ 16 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Fashion concepts in the perspective ........................................................................................... 18 1.1.1. Imitation and differentiation ................................................................................................ 18 1.1.2. Identity -

Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 1978 Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889 Joyce Marie Larson Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, and the Interior Design Commons Recommended Citation Larson, Joyce Marie, "Clothing of Pioneer Women of Dakota Territory, 1861-1889" (1978). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 5565. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/5565 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CWTHIFG OF PIONEER WOMEN OF DAKOTA TERRI'IORY, 1861-1889 BY JOYCE MARIE LARSON A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Haster of Science, Najor in Textiles, Clothing and Interior Design, South Dakota State University 1978 CLO'IHING OF PIONEER WOHEU OF DAKOTA TERRITORY, 1861-1889 This thesis is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the degree, Master of Science, and is acceptable for meeting the thesis requirements for this degree. Acceptance of this thesis does not imply that the conclusions reached by the candidate are necessarily the conclusions of the major department. Merlene Lyman� Thlsis Adviser Date Ardyce Gilbffet, Dean Date College of �ome Economics ACKNOWLEDGEr1ENTS The author wishes to express her warm and sincere appre ciation to the entire Textiles, Clothing and Interior Design staff for their assistance and cooperation during this research. -

The Nineteenth Century (History of Costume and Fashion Volume 7)

A History of Fashion and Costume The Nineteenth Century Philip Steele The Nineteenth Century Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2005 Bailey Publishing Associates Ltd Steele, Philip, 1948– Produced for Facts On File by A history of fashion and costume. Bailey Publishing Associates Ltd The Nineteenth Century/Philip Steele 11a Woodlands p. cm. Hove BN3 6TJ Includes bibliographical references and index. Project Manager: Roberta Bailey ISBN 0-8160-5950-0 Editor:Alex Woolf 1. Clothing and dress—History— Text Designer: Simon Borrough 19th century. 2. Fashion—History— Artwork: Dave Burroughs, Peter Dennis, 19th century. Tony Morris GT595.S74 2005 Picture Research: Glass Onion Pictures 391/.009/034—dc 22 Consultant:Tara Maginnis, Ph.D. 2005049453 Associate Professor of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and creator of the website,The The publishers would like to thank Costumer's Manifesto (http://costumes.org/). the following for permission to use their pictures: Printed and bound in Hong Kong. Art Archive: 17 (bottom), 19, 21 (top), All rights reserved. No part of this book may 22, 23 (left), 24 (both), 27 (top), 28 be reproduced or utilized in any form or by (top), 35, 38, 39 (both), 40, 41 (both), any means, electronic or mechanical, including 43, 44, 47, 56 (bottom), 57. photocopying, recording, or by any information Bridgeman Art Library: 6 (left), 7, 9, 12, storage or retrieval systems, without permission 13, 16, 21 (bottom), 26 (top), 29, 30, 36, in writing from the publisher. For information 37, 42, 50, 52, 53, 55, 56 (top), 58. contact: Mary Evans Picture Library: 10, 32, 45. -

Global Material Sourcing for the Clothing Industry

International Trade Centre UNCTAD/WTO Source-it Global material sourcing for the clothing industry Source it English copyright.pdf 1 2/17/2014 5:07:03 PM Source it English copyright.pdf 2 2/17/2014 5:07:18 PM International Trade Centre UNCTAD/WTO Source-it Global material sourcing for the clothing industry Geneva 2005 Source it English copyright.pdf 3 2/17/2014 5:07:18 PM ii ABSTRACT FOR TRADE INFORMATION SERVICES 2005 SITC 84 SOU INTERNATIONAL TRADE CENTRE UNCTAD/WTO Source-it – Global material sourcing for the clothing industry Geneva: ITC, 2005. xvi, 201 p. Guide dealing with dynamics of the global textiles and clothing supply chain, and why and how garment manufacturers need to develop alternative sourcing and supply management approaches – reviews historical background; discusses Chinese advantage in the international garment industry; explains different stages involved in material sourcing process; deals with fabric and trim sourcing; discusses politics of trade; includes case studies; appendices cover preferential access to the EU, summary of United States rules of origin, measures and conversions, and shipping terms/Incoterms; also includes glossary of related terms. Descriptors: Clothing, Textiles, Textile fabrics, Supply chain, Supply management, Value chain, Agreement on Textiles and Clothing English, French, Spanish (separate editions) ITC, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Trade Centre UNCTAD/WTO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

Maine Women and Fashion, 1790-1840

Maine History Volume 31 Number 1 My Best Wearing Apparel Maine Article 3 Women and Fashion, 1800-1840 3-1-1991 "So Monstrous Smart" : Maine Women and Fashion, 1790-1840 Kerry A. O'Brien York Institute Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Cultural History Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation O'Brien, Kerry A.. ""So Monstrous Smart" : Maine Women and Fashion, 1790-1840." Maine History 31, 1 (1991): 12-43. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol31/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Figure 3. N umber 4. 12 “So M onstrous S mart” (& ?£ ?£ ?$- ?£ ?& ?£ ^ ^ ^ “So Monstrous Smart”: Maine Women and Fashion, 1790 -1840 Kerry A. O'Brien When she died in 1836, Abigail Emerson of York, Maine, left her daughter, Clarissa, an intimate legacy: her clothing. In her will Mrs. Emerson itemized her “Best Wearing Apparel” : shimmies and drawers, caps, calash, stockings, long cotton shirt, Merino Shawl, Black lace veil, Bombazine gown, Silk Pelise, M uff and Tippet Clarissas inheritance included a dress of imported wool and silk twill, a soft wool shawl, a stylish veil, and a variety of caps, probably of thin white muslin. Outerwear also figured in Abigail Emerson s “best ap parel.” A silk coat-dress called a pelisse could have been worn as an outer garment. -

Costumer's Q!!Arterly Vol

costumer's Q!!arterly vol. 9, No. f oct/ Nov /Dec I 996 . j . ., . "- • !.... In This Issue The Victoria and Albert Museum w~rking With Feathers The Great Pattern Review The Fairy Tale Ball Pictorial Costumer's Quarterly Oct/Nov/Dec 1996 The Costumer's Quarterly Chapters 2824 Wellc Common. Fremont, CA 94555 Australian Costumer's Guild (The Wizards ofCos) Tel. 510.793.5895 c/o Wendy Purcell Email: [email protected] 39 Strattnore St. Bentleigh, Vtctoria 3204. Australia The Cosrumer's Quarterly is the official publication of The International Cos Sub-chapters: The Grey Company, Western Australia. Canberra tumer'sGuild, a SOI(c)(3) non-profit organization. Beyond Reality Coslumer's Guild PO Box 272, Dund«, OR 97115 Staff http:/www.hdix.nd/-lynxlguild.hunl Sally Nonon. Editor Zelda Gilbert, Copy Editor Costumer Guild UK Jana Keder, Production c/o Roddy, 12 Albert Road, London EIO 6PD Email: [email protected] The Cosrumer's Quarterly is copyright 1996 bY The International Costumer's Guild. All rights revert to the authors. photographers and artists upon publica Costumer's Guild West tion. PO Box 94538, Pasadena, CA 91 109 Voieemail : 818.759.8256 Copyrighted and trademarked names, symbols or designs used herein are pro http:llmembers.aol .comlzblgilbertlcgw.html vided solely for the furtherance of costuming interests and are not meant to Sub-chapter. San Diego Costumer's Guild (The Timeless Weavers) infringe on the copyright or trademark oftbe person, persons or company own 1341 E. Valley Parkway 11107, Escondido, CA 92027 ing the trademark. Sub-chapter. South Bay Costumer's Guild (Bombal:ine Bombers) clo Carole Parker 600 Fairmont Ave . -

Off the Cuff

Vandals off the cuff GEAR UP outerwear beanies masks + more! Homestuck? shop with a click at vandalstore.com This PDF is interactive! Try clicking here. 10% OFF PROMO CODE INSIDE 710 S. Deakin St Moscow, ID, 83843 (208) 885-6469 [email protected] Brave the cold, in Silver and Gold! As the seasons change, so should your gear! Celebrate your VandalPride in style with functional outerwear and chic accessories. Wind, snow, rain or shine, stay calm and Vandal On! @vandalstore Follow us! Take a picture and tag us using our handle on these social platforms while wearing your Vandal merch, and have the chance to be featured in our story! Save 10% on the products featured here! Enter this promo code during online checkout: OFFTHECUFF10 Table of Contents Information/PROMO 2 Outerwear 4 Accessories 8 Beanies 10-11 Drinkware 12-13 Masks 14-15 Shop our full inventory at vandalstore.com! 4 OUTERWEAR OUTERWEAR FEBRUARY COLLECTION 6 “Vandals Idaho” Plaid NEW! Goodie Hoodie Pullover Made for comfort, great for anything. This pullover hoodie will not disappoint. With a plaid in-lay lettering pattern along the chest, show off your VandalPride in a fresh take on an old-fashioned style! SKU: 2031304 $49.99 Click our products and shop now! Gear “Idaho” Big Cotton classic Sweatshirt Get that classic Vandal attire look with this Gear “Idaho” Big Cotton Sweatshirt! Made to keep you warm without sacrificing quality, this sweatshirt is perfect for any chilly weather that may come your way. Featuring a ribbed collar, V-notch cuffs and a blend of 80% cotton and 20% polyester, this sweatshirt has flair! SKU: 2005569 $49.99 Women’s “I-Vandals” Antigua Vest Whether you’re working out, running errands or just relaxing at home, this versatile hoodie will keep you comfortable.