Dropping out of High School and the Implications Over the Life Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domain-Specific Pseudonymous Signatures Revisited

Domain-Specific Pseudonymous Signatures Revisited Kamil Kluczniak Wroclaw University of Technology, Department of Computer Science [email protected] Abstract. Domain-Specific Pseudonymous Signature schemes were re- cently proposed for privacy preserving authentication of digital identity documents by the BSI, German Federal Office for Information Secu- rity. The crucial property of domain-specific pseudonymous signatures is that a signer may derive unique pseudonyms within a so called domain. Now, the signer's true identity is hidden behind his domain pseudonyms and these pseudonyms are unlinkable, i.e. it is infeasible to correlate two pseudonyms from distinct domains with the identity of a single signer. In this paper we take a critical look at the security definitions and construc- tions of domain-specific pseudonymous signatures proposed by far. We review two articles which propose \sound and clean" security definitions and point out some issues present in these models. Some of the issues we present may have a strong practical impact on constructions \provably secure" in this models. Additionally, we point out some worrisome facts about the proposed schemes and their security analysis. Key words: eID Documents, Privacy, Domain Signatures, Pseudonymity, Security Definition, Provable Security 1 Introduction Domain signature schemes are signature schemes where we have a set of users, an issuer and a set of domains. Each user obtains his secret keys in collaboration with the issuer and then may sign data with regards to his pseudonym. The crucial property of domain signatures is that each user may derive a pseudonym within a domain. Domain pseudonyms of a user are constant within a domain and a user should be unable to change his pseudonym within a domain, however, he may derive unique pseudonyms in each domain of the system. -

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide Represents the Most Requested Songs at Weddings and Parties

Elite Music Productions This Music Guide represents the most requested songs at Weddings and Parties. Please circle songs you like and cross out the ones you don’t. You can also write-in additional requests on the back page! WEDDING SONGS ALL TIME PARTY FAVORITES CEREMONY MUSIC CELEBRATION THE TWIST HERE COMES THE BRIDE WE’RE HAVIN’ A PARTY SHOUT GOOD FEELIN’ HOLIDAY THE WEDDING MARCH IN THE MOOD YMCA FATHER OF THE BRIDE OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL BACK IN TIME INTRODUCTION MUSIC IT TAKES TWO STAYIN ALIVE ST. ELMOS FIRE, A NIGHT TO REMEMBER, RUNAROUND SUE MEN IN BLACK WHAT I LIKE ABOUT YOU RAPPERS DELIGHT GET READY FOR THIS, HERE COMES THE BRIDE BROWN EYED GIRL MAMBO #5 (DISCO VERSION), ROCKY THEME, LOVE & GETTIN’ JIGGY WITH IT LIVIN, LA VIDA LOCA MARRIAGE, JEFFERSONS THEME, BANG BANG EVERYBODY DANCE NOW WE LIKE TO PARTY OH WHAT A NIGHT HOT IN HERE BRIDE WITH FATHER DADDY’S LITTLE GIRL, I LOVED HER FIRST, DADDY’S HANDS, FATHER’S EYES, BUTTERFLY GROUP DANCES KISSES, HAVE I TOLD YOU LATELY, HERO, I’LL ALWAYS LOVE YOU, IF I COULD WRITE A SONG, CHICKEN DANCE ALLEY CAT CONGA LINE ELECTRIC SLIDE MORE, ONE IN A MILLION, THROUGH THE HANDS UP HOKEY POKEY YEARS, TIME IN A BOTTLE, UNFORGETTABLE, NEW YORK NEW YORK WALTZ WIND BENEATH MY WINGS, YOU LIGHT UP MY TANGO YMCA LIFE, YOU’RE THE INSPIRATION LINDY MAMBO #5BAD GROOM WITH MOTHER CUPID SHUFFLE STROLL YOU RAISE ME UP, TIMES OF MY LIFE, SPECIAL DOLLAR WINE DANCE MACERENA ANGEL, HOLDING BACK THE YEARS, YOU AND CHA CHA SLIDE COTTON EYED JOE ME AGAINST THE WORLD, CLOSE TO YOU, MR. -

Towards Formal Definitions

Covid Notions: Towards Formal Definitions – and Documented Understanding – of Privacy Goals and Claimed Protection in Proximity-Tracing Services Christiane Kuhn∗, Martin Becky, Thorsten Strufe∗z ∗ KIT Karlsruhe, fchristiane.kuhn, [email protected] y Huawei, [email protected] z Centre for Tactile Internet / TU Dresden April 17, 2020 Abstract—The recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemic gave rise to they are at risk, if they have been in proximity with another management approaches using mobile apps for contact tracing. individual that later tested positive for the disease), their The corresponding apps track individuals and their interactions, architecture (most protocols assume a server to participate in to facilitate alerting users of potential infections well before they become infectious themselves. Na¨ıve implementation obviously the service provision, c.f. PEPP-PT, [1], [2], [8]), and broadly jeopardizes the privacy of health conditions, location, activities, the fact that they assume some adversaries to aim at extracting and social interaction of its users. A number of protocol designs personal information from the service (sometimes also trolls for colocation tracking have already been developed, most of who could abuse, or try to sabotage the service or its users3). which claim to function in a privacy preserving manner. How- Most, if not all published proposals claim privacy, ever, despite claims such as “GDPR compliance”, “anonymity”, “pseudonymity” or other forms of “privacy”, the authors of these anonymity, or compliance with some data protection regu- designs usually neglect to precisely define what they (aim to) lations. However, none, to the best of our knowledge, has protect. actually formally defined threats, trust assumptions and ad- We make a first step towards formally defining the privacy versaries, or concrete protection goals. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Relational-Cultural Perspectives of African American Women with Diabetes and Maintaining Multiple Roles

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses November 2017 Relational-Cultural Perspectives of African American Women with Diabetes and Maintaining Multiple Roles Ayesha Ali University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Other Nursing Commons Recommended Citation Ali, Ayesha, "Relational-Cultural Perspectives of African American Women with Diabetes and Maintaining Multiple Roles" (2017). Doctoral Dissertations. 1042. https://doi.org/10.7275/10586793.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1042 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Relational-Cultural Perspectives of African American Women with Diabetes and Maintaining Multiple Roles A Dissertation Presented by Ayesha Ali Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2017 College of Nursing © Copyright by Ayesha Ali 2017 All Rights Reserved RELATIONAL-CULTURAL PERSPECTIVES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN WITH DIABETES AND MAINTAINING MULTIPLE ROLES A Dissertation Presented By AYESHA ALI Approved as to style and content by: ________________________________________ Cynthia S. Jacelon, Chair ________________________________________ Genevieve E. Chandler, Member ________________________________________ Alexandrina Deschamps, Member ______________________________ Stephen Cavanagh, Dean College of Nursing DEDICATION This is dedicated to my mother and my always supportive husband. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give a heart-felt thanks to my advisor and chair of my dissertation committee, Cynthia Jacelon. -

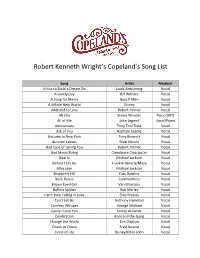

Robert Kenneth Wright's Copeland's Song List

Robert Kenneth Wright’s Copeland’s Song List Song Artist Medium A Kiss to Build a Dream On Louis Armstrong Vocal A Lovely Day Bill Withers Vocal A Song for Mama Boyz II Men Vocal A Whole New World Disney Vocal Addicted to Love Robert Palmer Vocal All I Do Stevie Wonder Piano (WT) All of Me John Legend Vocal/Piano Anniversary Tony Toni Tone Vocal Ask of You Raphael Saadiq Vocal Autumn in New York Tony Bennett Vocal Autumn Leaves Matt Monro Vocal Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Vocal Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Vocal Beat It Michael Jackson Vocal Before I Let Go Frankie Beverly/Maze Vocal Billie Jean Michael Jackson Vocal Blueberry Hill Fats Domino Vocal Brick House Commodores Vocal Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Vocal Buffalo Soldier Bob Marley Vocal Can’t Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Vocal Can’t Let Go Anthony Hamilton Vocal Careless Whisper George Michael Vocal Cause I Love You Lenny Williams Vocal Celebration Kool and the Gang Vocal Change the World Eric Clapton Vocal Cheek to Cheek Fred Astaire Vocal Circle of Life Disney/Elton John Vocal Close the Door Teddy Pendergrass Vocal Cold Sweat James Brown Vocal Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vocal Creepin’ Luther Vandross Vocal Dat Dere Tony Bennett Vocal Distant Lover Marvin Gaye Vocal Don’t Stop Believing Journey Vocal Don’t Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Vocal Don’t You Know That Luther Vandross Vocal Early in the Morning Gap Band Vocal End of the Road Boyz II Men Vocal Every Breath You Take The Police Vocal Feelin’ on Ya Booty R. -

PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST

TITLE NO ARTIST 22 5050 TAYLOR SWIFT 214 4261 RIVER MAYA ( I LOVE YOU) FOR SENTIMENTALS REASONS SAM COOKEÿ (SITTIN’ ON) THE DOCK OF THE BAY OTIS REDDINGÿ (YOU DRIVE ME) CRAZY 4284 BRITNEY SPEARS (YOU’VE GOT) THE MAGIC TOUCH THE PLATTERSÿ 19-2000 GORILLAZ 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN 9-1-1 EMERGENCY SONG 1 A BIG HUNK O’ LOVE 2 ELVIS PRESLEY A BOY AND A GIRL IN A LITTLE CANOE 3 A CERTAIN SMILE INTROVOYS A LITTLE BIT 4461 M.Y.M.P. A LOVE SONG FOR NO ONE 4262 JOHN MAYER A LOVE TO LAST A LIFETIME 4 JOSE MARI CHAN A MEDIA LUZ 5 A MILLION THANKS TO YOU PILITA CORRALESÿ A MOTHER’S SONG 6 A SHOOTING STAR (YELLOW) F4ÿ A SONG FOR MAMA BOYZ II MEN A SONG FOR MAMA 4861 BOYZ II MEN A SUMMER PLACE 7 LETTERMAN A SUNDAY KIND OF LOVE ETTA JAMESÿ A TEAR FELL VICTOR WOOD A TEAR FELL 4862 VICTOR WOOD A THOUSAND YEARS 4462 CHRISTINA PERRI A TO Z, COME SING WITH ME 8 A WOMAN’S NEED ARIEL RIVERA A-GOONG WENT THE LITTLE GREEN FROG 13 A-TISKET, A-TASKET 53 ACERCATE MAS 9 OSVALDO FARRES ADAPTATION MAE RIVERA ADIOS MARIQUITA LINDA 10 MARCO A. JIMENEZ AFRAID FOR LOVE TO FADE 11 JOSE MARI CHAN AFTERTHOUGHTS ON A TV SHOW 12 JOSE MARI CHAN AH TELL ME WHY 14 P.D. AIN’T NO MOUNTAIN HIGH ENOUGH 4463 DIANA ROSS AIN’T NO SUNSHINE BILL WITHERSÿ AKING MINAHAL ROCKSTAR 2 AKO ANG NAGTANIM FOLK (MABUHAY SINGERS)ÿ AKO AY IKAW RIN NONOY ZU¥IGAÿ AKO AY MAGHIHINTAY CENON LAGMANÿ AKO AY MAYROONG PUSA AWIT PAMBATAÿ PH - Songs on Streaming Server 1 TITLE NO ARTIST AKO NA LANG ANG LALAYO FREDRICK HERRERA AKO SI SUPERMAN 15 REY VALERA AKO’ Y NAPAPA-UUHH GLADY’S & THE BOXERS AKO’Y ISANG PINOY 16 FLORANTE AKO’Y IYUNG-IYO OGIE ALCASIDÿ AKO’Y NANDIYAN PARA SA’YO 17 MICHAEL V. -

A Signature Scheme with Unlinkable-Yet-Acountable Pseudonymity for Privacy-Preserving Crowdsensing

A Signature Scheme with Unlinkable-yet-Acountable Pseudonymity for Privacy-Preserving Crowdsensing Victor Sucasas, IEEE Member; Georgios Mantas, IEEE Member; Joaquim Bastos; Francisco Damia˜o; Jonathan Rodriguez, IEEE Senior Member Abstract—Crowdsensing requires scalable privacy-preserving Smart City and crowdsensing participants. From the Smart City authentication that allows users to send anonymously sensing perspective the security concern is twofold. Firstly, sensors reports, while enabling eventual anonymity revocation in case are distributed and carried be citizens who could be malicious of user misbehavior. Previous research efforts already provide users sensing fake data or honest users with defective sensors. efficient mechanisms that enable conditional privacy through Secondly, citizens are rewarded for contributing to the sensing pseudonym systems, either based on Public Key Infrastructure tasks, and hence selfish users could submit their reports several (PKI) or Group Signature (GS) schemes. However, previous schemes do not enable users to self-generate an unlimited number times to increase their profits. From the citizens’ perspective of pseudonyms per user to enable users to participate in diverse the main concern is the location privacy, since crowdsensing sensing tasks simultaneously, while preventing the users from participants submit sensing data together with geolocation participating in the same task under different pseudonyms, which information [7]. Thus the Smart City can identify and locate is referred to as sybil attack. This paper addresses this issue by citizens, which can discourage citizens from participating in providing a scalable privacy-preserving authentication solution the sensing tasks [8],[9],[10]. for crowdsensing, based on a novel pseudonym-based signature scheme that enables unlinkable-yet-accountable pseudonymity. -

The Indexing of Welsh Personal Names

The indexing of Welsh personal names Donald Moore Welsh personal names sometimes present the indexer with problems not encountered when dealing with English names. The Welsh patronymic system of identity is the most obvious; this was normal in the Middle Ages, and traces of its usage survived into the mid-nineteenth century. Patronymics have since been revived as alternative names in literary and bardic circles, while a few individuals, inspired by the precedents of history, are today attempting to use them regularly in daily life. Other sorts of alternative names, too, have been adopted by writers, poets, artists and musicians, to such effect that they are often better known to the Welsh public than the real names. A distinctive pseudonym has a special value in Wales, where a restricted selection of both first names and surnames has been the norm for the last few centuries. Apart from the names themselves, there is in Welsh a linguistic feature which can be disconcerting to those unfamiliar with the language: the 'mutation' or changing of the initial letter of a word in certain phonetic and syntactic contexts. This can also occur in place-names, which were discussed by the present writer in The Indexer 15 (1) April 1986. Some of the observations made there about the Welsh language will be relevant here also. Indexing English names 'Fitzwarin family' under 'F' and 'Sir John de la Mare' According to English practice a person is indexed under 'D' (the last, though French, being domiciled in under his or her surname. First names, taken in England).1 alphabetical order, word by word, are then used to Indexing Welsh names determine the sequence of entries when the same English conventions of nomenclature apply today in surname recurs in the index ('first' = 'Christian' = Wales as much as in England, but there are three 'baptismal' = 'given' = 'forename'). -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

Daryl Lowery Sample Songlist Bridal Songs

DARYL LOWERY SAMPLE SONGLIST BRIDAL SONGS Song Title Artist/Group Always And Forever Heatwave All My Life K-Ci & Jo JO Amazed Lonestar At Last Etta James Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Breathe Faith Hill Can't Help Falling In Love Elvis Presley Come Away With Me Nora Jones Could I Have This Dance Anne Murray Endless Love Lionel Ritchie & Diana Ross (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams From This Moment On Shania Twain & Brian White Have I Told You Lately Rod Stewart Here And Now Luther Van Dross Here, There And Everywhere Beatles I Could Not Ask For More Edwin McCain I Cross My Heart George Strait I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees I Don't Want To Miss A Thing Aerosmith I Knew I Loved You Savage Garden I'll Always Love You Taylor Dane In Your Eyes Peter Gabriel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel Keeper Of The Stars Tracy Byrd Making Memories Of Us Keith Urban More Than Words Extreme One Wish Ray J Open Arms Journey Ribbon In The Sky Stevie Wonder Someone Like You Van Morrison Thank You Dido That's Amore Dean Martin The Way You Look Tonight Frank Sinatra The Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler Unchained Melody Righteous Brothers What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong When A Man Loves A Woman Percy Sledge Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton You And Me Lifehouse You're The Inspiration Chicago Your Song Elton John MOTHER/SON DANCE Song Title Artist/Group A Song For Mama Boyz II Men A Song For My Son Mikki Viereck You Raise Me Up Josh Groban Wind Beneath My Wings Bette Midler FATHER/DAUGHTER DANCE Song Title Artist/Group Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Butterfly Kisses Bob Carlisle Daddy's Little Girl Mills Brothers Unforgettable Nat & Natalie King Cole What A Wonderful World Louis Armstrong Popular Selections: "Big Band” To "Hip Hop" Song Title Artist/Group (Oh What A Night) December 1963 Four Seasons 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 21 Questions 50 Cent 867-5309 Tommy Tutone A New Day Has Come Celine Dion A Song For My Son Mikki Viereck A Thousand Years Christine Perri A Wink And A Smile Harry Connick, Jr.