The Following English-Language Excerpts Are Provided to Give

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Sea-Caspian Steppe: Natural Conditions 20 1.1 the Great Steppe

The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editors Florin Curta and Dušan Zupka volume 74 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee The Pechenegs: Nomads in the Political and Cultural Landscape of Medieval Europe By Aleksander Paroń Translated by Thomas Anessi LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Publication of the presented monograph has been subsidized by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education within the National Programme for the Development of Humanities, Modul Universalia 2.1. Research grant no. 0046/NPRH/H21/84/2017. National Programme for the Development of Humanities Cover illustration: Pechenegs slaughter prince Sviatoslav Igorevich and his “Scythians”. The Madrid manuscript of the Synopsis of Histories by John Skylitzes. Miniature 445, 175r, top. From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. Proofreading by Philip E. Steele The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://catalog.loc.gov/2021015848 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco

From Triumphal Gates to Triumphant Rotting: Refractions of Rome in the Russian Political Imagination by Olga Greco A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Valerie A. Kivelson, Chair Assistant Professor Paolo Asso Associate Professor Basil J. Dufallo Assistant Professor Benjamin B. Paloff With much gratitude to Valerie Kivelson, for her unflagging support, to Yana, for her coffee and tangerines, and to the Prawns, for keeping me sane. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication ............................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter I. Writing Empire: Lomonosov’s Rivalry with Imperial Rome ................................... 31 II. Qualifying Empire: Morals and Ethics of Derzhavin’s Romans ............................... 76 III. Freedom, Tyrannicide, and Roman Heroes in the Works of Pushkin and Ryleev .. 122 IV. Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov and the Rejection of the Political [Rome] .................. 175 V. Blok, Catiline, and the Decomposition of Empire .................................................. 222 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 271 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................... -

Phenomena Magazine June 2015

PUBLISHED BY MAPIT MAPIT 2015 Brought to you by MAPIT: Est. 1974. EDITORIAL Dear All, well another month and another conference, this time in Scotland’s capital city. I was speaking at a UFO and Paranormal conference in the Pleasance Theatre in Edinburgh and thoroughly enjoyed it too. A good bunch of speakers and a good selection of subjects covered, I was giving the ‘Truth, Lies and Ufology’ presentation, I promise you, of all the presentations that I give this is the one I keep being asked to give. I’m not altogether sure why, maybe it’s because it makes people think and challenges their preconceptions a bit, who knows, but whatever the reason it does seem popular. The aim is to make this as an annual event, hopefully this will happen, if for no other reason than Scotland does not have one. The paranormal is an infinitely fascinating area of research that knows no boundaries because, like it or not and whether we realise it or not, it influences every single area of our lives. My apologies to those of a reli- gious persuasion who regard the paranormal and any of its attributes as an absolute anathema, but when all is said and done, religion is another facet of the paranormal. An example of this is the phenomenon of mira- cles which are apparently brought about by prayer; this shows that a form of words, a ‘prayer’ is an exact analogue of a magick spell. In the same role clergymen are analogues of sorcerers. Magick has been de- scribed as the ability to influence reality by an act of will alone and whether this act of will is a prayer or a spell it makes no difference. -

The Roles of Geographical Concepts in the Construction of Ancient Greek

The Roles of Geographical Concepts in the Construction of Ancient Greek Ethno-cultural Identities, from Homer to Herodotus: An Analysis of the Continents and the Mediterranean Sea Cameron McPhail A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand December 2015 Contents Acknowledgements ii List of Abbreviations iii-viii List of Figures ix-x Abstract xi Introduction 1-11 1. A Review of the Primary and Secondary Source Material on Ancient Greek Ethno-cultural Identity Construction 12-50 2. The Theory of Ancient Greek Geographical Ethnocentrism: Locating Hellas and the Mediterranean Sea within the Conceptual Structure of the Oikoumene 51-93 3. The Genesis of the Continental System in Ancient Greek Geographical Thought and its Associations with Ethno-cultural Identity Construction 94-127 4. The Continents and the Evolution of Ancient Greek Ethno-cultural Self- definition in the Athenian Wartime Context: A Case Study of Aeschylus’ Persians 128-164 5. The Herodotean Perspective: Geography and Ethno-cultural Identity in the Histories 165-214 Conclusion 215-220 Bibliography 221-256 Cover Illustration: A modern reconstruction of Hecataeus of Miletus’ world map (c. 500 BC). The continents and the Mediterranean Sea together form the basic geographical structure of the map. Source: Virga (2007) 15, plate 12. i Acknowledgements After more than four years spent writing this thesis, there are, of course, several important people to whom I am greatly indebted. These people have helped make the PhD experience much less daunting and stressful than it otherwise could have been. First, I cannot thank enough my supervisors Associate Prof. -

Luís Vaz De Camões and Maciej Stryjkowski)*

© 2018 Author(s). Open Access. This article is “Studi Slavistici”, xv, 2018, 2: 39-54 distributed under the terms of the cc by-nc-nd 4.0 doi: 10.13128/Studi_Slavis-23724 Submitted on 2018, July 21st issn 1824-761x (print) Accepted on 2018, October 19th issn 1824-7601 (online) Jakub Niedźwiedź Where Are We in Europe? Two Literary Maps of the Continent in Renaissance Epic Poetry (Luís Vaz de Camões and Maciej Stryjkowski)* In my paper I am going to examine two epic texts written in the 1560s and 1570s, one in the Kingdom of Portugal, the other in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. There are several striking resemblances between these texts but I would like to focus on only one of them: the literary mapping of Europe. I will attempt to answer the question as to how maps permeated Renaissance epic poetry and I will examine the problem of the early modern cartographical production of national space (Hampton 2001: 130-149, Padrón 2004: 185, Conley 2007: 407). However, my main aim is not to prove that Stryjkowski and Camões saw or consulted specific maps. Many historical and literary studies published in the last three decades show that cartography influenced early modern literature and there is no need to prove it again (Conley 1987, Olson 1994: 195-232, Nuti 1999, Cosgrove 2001, Hampton 2001: 109-149, Klein 2001: 133-187, Padrón 2004, Jacob 2006, Conley 2007, Conley 2011, Veneri 2012: 29-48, Engberg-Pedersen 2017, Piechocki 2019). My intention is rather to show how Portuguese and Polish poets used some rhetorical tools (figures of speech) to construct literary maps. -

Frankish and Merovingian Origin Location(S)

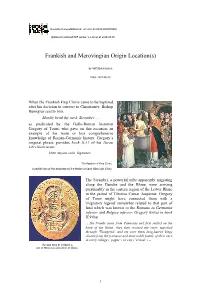

Deutsche Nationalbibliothek urn:nbn:de:0233-2019070510 Update for archived PDF version v.1.00 as of 2019-07-05 Frankish and Merovingian Origin Location(s) by Rolf Badenhausen Date: 2021-08-23 When the Frankish king Clovis came to be baptized after his decision to convert to Christianity, Bishop Remigius said to him, Meekly bend thy neck, Sicamber ... , as predicated by the Gallo-Roman historian Gregory of Tours, who gave on this occasion an example of his more or less comprehensive knowledge of Roman-Germanic history. Gregory’s original phrase provides book II,31 of his Decem Libri Historiarum : Mitis depone colla, Sigamber... The Baptism of King Clovis. A partial view of the altarpiece by the Master of Saint Gilles (abt 1500). The Sicambri, a powerful tribe apparently migrating along the Danube and the Rhine, were arriving presumably in the eastern region of the Lower Rhine in the period of Tiberius Caesar Augustus. Gregory of Tours might have connected them with a 'migratory legend' somewhat related to that part of land which was known to the Romans as Germania inferior and Belgica inferior . Gregory writes in book II,9 that ... the Franks came from Pannonia and first settled on the bank of the Rhine; they then crossed the river, marched through 'Thongeria', and set over them long-haired kings chosen from the foremost and most noble family of their race in every village ‹ 'pagus' › or city ‹ 'civitas' › ... The Seal Ring of Childeric I, son of Meroveus and father of Clovis. 1 Migration of early Franks or 'Salian Franks'. Pannonia or Baunonia ? As quoted above, Gregory of Tours actually maintains that the Franks migrated from 'Pannonia' into their well known later domain, which then, since 4 th century, was formed mainly on the left bank of the Rhine. -

The Strange Races on the Hereford Mappa Mundi: an Investigation of Sources

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2001 The Strange Races on the Hereford Mappa Mundi: An Investigation of Sources John H. Chandler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chandler, John H., "The Strange Races on the Hereford Mappa Mundi: An Investigation of Sources" (2001). Master's Theses. 3934. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3934 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE STRANGE RACES ON THE HEREFORD MPPA MD!: AN INVESTIGATION OF SOURCES by John H. Chandler A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements forthe Degreeof Master of Arts The Medieval Institute WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2001 THE STRANGE RACES ON THE HEREFORD MPPA MD/: AN INVESTIGATION OF SOURCES John H. Chandler, M.A. WesternMichigan University,2001 The Hereford Mappa Mundi, a thirteenth-century world map, includes mention of fifty-four strange races. Many of the races can be found in three earlier sources: Pliny's Natura/is historia, Solinus's Collectanea rerum memorabilium, and Isidore's Etymologiae. By comparison to these three sources, the works used by the author of the map will be made clear. This study provides an edition of all the inscriptions relating to these races, and compares them to excerpts relating to the races from the three above sources, as well as St. -

The Gael and Cymbri, Or, an Inquiry Into the Origin and History of the Irish Scoti, Britons, and Gauls, and of the Caledonians

SoldlA- '^y \\j(XmAIms.e^c ^^ y^^.y^ \^yvv7/^ ^^ /^r^- ^^T^ -/^.^v ^-^- A^-^y : GAEL AND CYMBRI; AN INQUIRY INTO THE ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE IRISH SCOTI, BRITONS, AND GAULS, AND OF THE CALEDONIANS, PICTS, WELSH, CORNISH, AND BRETONS. BY SIR WILLIAM BETHAM, ULSTER KING OP ARMS, &C &C. DUBLIN WILLIAM CURRY, JUN. AND CO. SIMPKIN AND MARSHALL, AND T. AND W. BOONE, LONDON; OLIVER AND BOYD, EDINBURGH. 1834. I'HINTKIl UY P 1) lliRIlY, 3, CECIL TO THE KING. Sire, I have the honour to inscribe to your most gracious Majesty, this attempt to place on its true basis, the history of the early inhabitants of the British Islands ; which, I trust, will be found not altogether unworthy your Majesty's royal favour and patronage. With the most humble, grateful, and duti- ful respect, I have the honour to subscribe myself. Your Majesty's most devoted Servant and Subject, WILLIAI^I BETHAM, Ulster King of Arras. PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS. The family of the liiiman race from which the Milesian Irish derive their descent, and the period of their settlement in Ireland, has been, hitherto, a much disputed, but unsettled question. The native authorities, indeed, derive them from Spain, and call them Scoti, or Scuits, but it is still left doubtful who these Scoti were, as no such people are mentioned by the antient writers as inhabiting Spain ; and the authority of the Irish MSS. and traditions has been altogether re- jected by some, and held as very questionable authority, by most English writers, while the a VI PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS. -

Luis Vaz De Camoes and Maciej Stryjkowski

© 2018 Author(s). Open Access. This article is “Studi Slavistici”, xv, 2018, 2: 39-54 distributed under the terms of the cc by-nc-nd 4.0 doi: 10.13128/Studi_Slavis-23724 Submitted on 2018, July 21st issn 1824-761x (print) Accepted on 2018, October 19th issn 1824-7601 (online) Jakub Niedźwiedź Where Are We in Europe? Two Literary Maps of the Continent in Renaissance Epic Poetry (Luís Vaz de Camões and Maciej Stryjkowski)* In my paper I am going to examine two epic texts written in the 1560s and 1570s, one in the Kingdom of Portugal, the other in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. There are several striking resemblances between these texts but I would like to focus on only one of them: the literary mapping of Europe. I will attempt to answer the question as to how maps permeated Renaissance epic poetry and I will examine the problem of the early modern cartographical production of national space (Hampton 2001: 130-149, Padrón 2004: 185, Conley 2007: 407). However, my main aim is not to prove that Stryjkowski and Camões saw or consulted specific maps. Many historical and literary studies published in the last three decades show that cartography influenced early modern literature and there is no need to prove it again (Conley 1987, Olson 1994: 195-232, Nuti 1999, Cosgrove 2001, Hampton 2001: 109-149, Klein 2001: 133-187, Padrón 2004, Jacob 2006, Conley 2007, Conley 2011, Veneri 2012: 29-48, Engberg-Pedersen 2017, Piechocki 2019). My intention is rather to show how Portuguese and Polish poets used some rhetorical tools (figures of speech) to construct literary maps. -

In Northern Mists; Arctic Exploration in Early Times

i % 'I'M "';'(: In.T/il.'' .;-ifi:o;; >v ;''{ , t . IN NORTHERN MISTS VOL. I. "THE GOLDEN CLOUDS CURTAINED THE DEEP WHERE IT LAY, AND IT LOOKED LIKE AN EDEN AWAY, FAR AWAY." IN NORTHERN MISTS ARCTIC EXPLORATION IN EARLY TIMES BY FRIDTJOF NANSEN G.C.V.O., D.Sc, D.C.L., Ph.D. Professor of Oceanography in the University of Christiania, Etc. AUTHOR OF "FARTHEST NORTH" TRANSLATED BY ARTHUR G. CHATER 2.11 N IN TWO VOLUMES WITH FRONTISPIECES IN COLOR, AND OVER ONE HUNDRED AND FIFTY ILLUSTRATIONS IN BLACK-AND-WHITE VOL. I. "•' ;..'•••••' :'':'' Copyright, JQII, by Frederick A. Stokes Company Alt rights reser'ved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandtna'vian Nonjember, igii H 1^ PREFACE THIS book owes its existence in the first instance to a rash promise made some years ago to my friend. Dr. J. Scott Keltie, of London, that I would try, when time permitted, to contribute a volume on the history of arctic voy- ages to his series of books on geographical exploration. The subject was an attractive one; I thought I was fairly familiar with it, and did not expect the book to take a very long time when once I made a start with it. On account of other studies it was a long while before I could do this; but when at last I seriously took the work in hand, the subject, in return, monopo- lized my whole powers. It appeared to me that the natural foundation for a history of arctic voyages was, in the first place, to make clear the main features in the development of knowledge of the North in early times. -

Episode #2 Part 2 the Hyperborean Myth

EPISODE #2 PART 2 THE HYPERBOREAN MYTH Following on from our last episode, we now return to the Hyperboreans, as we explore deeper into the writings of the ancients who spoke of them, from Herodotus to Pindar, and look into what exactly they had to say. Our last episode was focused mainly on the scientific evidence of the High North as the origin point of our people, whereas this one will be more poetic and mythological. We'll also be looking into the Traditions that have been left to us by these Hyperboreans, and the festivals still celebrated across Europe to this day. The nature of the subject matter means that there are a lot of references to texts written by ancient poets and historians, and if we were to simply read from them all, it would've taken up a considerable amount of the episode. So, instead, we have saved the readings for only the most important parts, and we will include the rest both in our 'further reading' section and in the script for the episode, that will be published shortly. As always, this episode must come with a preface that the promotion of love for one's own people is not to be equated with the promotion of hatred for others – and in these politically turbulent times, such clarifications are unfortunately necessary. The Greeks, Celts and Romans all spoke frequently of a Divine race of beings in the North, throughout both their history and their mythology. In fact, it can become quite difficult to discern what is myth, what is history, and what is simply poetic allegory, but there is truth within all three. -

Restoration Uranography, Dryden's Judicial Astrology, and the Fate of Anne Killigrew

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 4-30-2010 The Pleiadic Age of Stuart Poesie: Restoration Uranography, Dryden's Judicial Astrology, and the Fate of Anne Killigrew Morgan Alexander Brown Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Morgan Alexander, "The Pleiadic Age of Stuart Poesie: Restoration Uranography, Dryden's Judicial Astrology, and the Fate of Anne Killigrew." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PLEIADIC AGE OF STUART POËSIE: RESTORATION URANOGRAPHY, DRYDEN'S JUDICIAL ASTROLOGY, AND THE FATE OF ANNE KILLIGREW by Morgan A. Brown Under the Direction of Tanya Caldwell ABSTRACT: The following Thesis is a survey of seventeenth-century uranography, with specific focus on the use of the Pleiades and Charles's Wain by English poets and pageant writers as astrological ciphers for the Stuart dynasty (1603-1649; 1660-1688). I then use that survey to address the problem of irony in John Dryden's 1685 Pindaric elegy, "To the Pious Memory of Mrs. Anne Killigrew," since the longstanding notion of what the Pleiades signify in Dryden's ode is problematic from an astronomical and astrological perspective. In his elegiac ode, Dryden translates a young female artist to the Pleiades to actuate her apotheosis, not for the sake of mere fulsome hypberbole, but in such a way that Anne (b.