The Gael and Cymbri, Or, an Inquiry Into the Origin and History of the Irish Scoti, Britons, and Gauls, and of the Caledonians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE KINGS and QUEENS of BRITAIN, PART I (From Geoffrey of Monmouth’S Historia Regum Britanniae, Tr

THE KINGS AND QUEENS OF BRITAIN, PART I (from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, tr. Lewis Thorpe) See also Bill Cooper’s extended version (incorporating details given by Nennius’s history and old Welsh texts, and adding hypothesised dates for each monarch, as explained here). See also the various parallel versions of the Arthurian section. Aeneas │ Ascanius │ Silvius = Lavinia’s niece │ Corineus (in Cornwall) Brutus = Ignoge, dtr of Pandrasus │ ┌─────────────┴─┬───────────────┐ Gwendolen = Locrinus Kamber (in Wales) Albanactus (in Scotland) │ └Habren, by Estrildis Maddan ┌──┴──┐ Mempricius Malin │ Ebraucus │ 30 dtrs and 20 sons incl. Brutus Greenshield └Leil └Rud Hud Hudibras └Bladud │ Leir ┌────────────────┴┬──────────────┐ Goneril Regan Cordelia = Maglaurus of Albany = Henwinus of Cornwall = Aganippus of the Franks │ │ Marganus Cunedagius │ Rivallo ┌──┴──┐ Gurgustius (anon) │ │ Sisillius Jago │ Kimarcus │ Gorboduc = Judon ┌──┴──┐ Ferrex Porrex Cloten of Cornwall┐ Dunvallo Molmutius = Tonuuenna ┌──┴──┐ Belinus Brennius = dtr of Elsingius of Norway Gurguit Barbtruc┘ = dtr of Segnius of the Allobroges └Guithelin = Marcia Sisillius┘ ┌┴────┐ Kinarius Danius = Tanguesteaia Morvidus┘ ┌──────┬────┴─┬──────┬──────┐ Gorbonianus Archgallo Elidurus Ingenius Peredurus │ ┌──┴──┐ │ │ │ (anon) Marganus Enniaunus │ Idvallo Runo Gerennus Catellus┘ Millus┘ Porrex┘ Cherin┘ ┌─────┴─┬───────┐ Fulgenius Edadus Andragius Eliud┘ Cledaucus┘ Clotenus┘ Gurgintius┘ Merianus┘ Bledudo┘ Cap┘ Oenus┘ Sisillius┘ ┌──┴──┐ Bledgabred Archmail └Redon └Redechius -

Some Rare and Unpublished Ancient British Coins

AN ACCOUNT OF SOME RARE AND UNPUBLISHED ANCIENT BRITISH COINS, COMMUNICATED TO THE NUMISMATIC SOCIETY OF LONDON BY JOHN EVANS, F.S.A., F.G.S., HON. SEC. NUM.SOC. LONDON: 1860. 1·~~~ ANCIENT BRITISH COi NS. AN ACCOUNT or SOME RARE AND UNPUBLISHED ANCIENT BRITISH COINS, COMMUNICATED TO THE NUMISMATIC SOCIETY OF LONDON BY JOHN EVANS, F.S. .A., F.G.S., BON. SBC. NUM. SOC. LONDON: 1860. Stack Annex !:>01.5346 SOME RARE AND UNPUBLISHED ANCIENT BRITISH COINS. Read before the Numismatic Society, Jan. 26th, 1860.] r HAVE again the satisfaction of presenting to the Society a plate of ancient British coins, most ofof them hithetto un- published, and all of the highest degree of rarity. Unlike the last miscellaneous plate of these coins that I , drew, which consisted entirely of uninscrihed coins, these areall i11scribed, and comprise Specimens of the coinage of Cuno beline, Taseiovanus, Dubnovellaunus, and the Iceni, beside others of rather more doubtful attribution. l need not, however, make any prefatory remarks conceming them, hut will at once proceed to the description of the various coins, and the considerations which arc suggested by thei1· several types and inscriptions. T'he first three are of Cunobeline. No. 1. Obv. - CA-MVon either side of an ear of bearded corn, as usual on the gold coins of Cunobeline, hut rather more widely spread. The stalk terminating in an ornament shaped like Gothic trefoil. Rev.-CVNO beneath a horse, galloping, to the left; ahove, an ornament, in shape like the Prince of Wales' plume, resting on a reversed crescent. -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

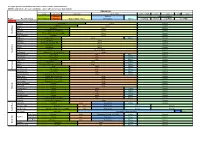

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

The Scotch-Irish in America. ' by Samuel, Swett Green

32 American Antiquarian Society. [April, THE SCOTCH-IRISH IN AMERICA. ' BY SAMUEL, SWETT GREEN. A TRIBUTE is due from the Puritan to the Scotch-Irishman,"-' and it is becoming in this Society, which has its headquar- ters in the heart of New England, to render that tribute. The story of the Scotsmen who swarmed across the nar- row body of water which separates Scotland from Ireland, in the seventeenth century, and who came to America in the eighteenth century, in large numbers, is of perennial inter- est. For hundreds of years before the beginning of the seventeenth centurj' the Scot had been going forth con- tinually over Europe in search of adventure and gain. A!IS a rule, says one who knows him \yell, " he turned his steps where fighting was to be had, and the pay for killing was reasonably good." ^ The English wars had made his coun- trymen poor, but they had also made them a nation of soldiers. Remember the "Scotch Archers" and the "Scotch (juardsmen " of France, and the delightful story of Quentin Durward, by Sir Walter Scott. Call to mind the " Scots Brigade," which dealt such hard blows in the contest in Holland with the splendid Spanish infantry which Parma and Spinola led, and recall the pikemen of the great Gustavus. The Scots were in the vanguard of many 'For iickiiowledgments regarding the sources of information contained in this paper, not made in footnotes, read the Bibliographical note at its end. ¡' 2 The Seotch-líiáh, as I understand the meaning of the lerm, are Scotchmen who emigrated to Ireland and such descendants of these emigrants as had not through intermarriage with the Irish proper, or others, lost their Scotch char- acteristics. -

Shakespeare on Travel in As You Like It and Othello

Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference Volume 11 Article 4 2020 Knowing the World: Shakespeare on Travel in As You Like It and Othello David Summers Capital University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Recommended Citation Summers, David (2020) "Knowing the World: Shakespeare on Travel in As You Like It and Othello," Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference: Vol. 11 , Article 4. Available at: https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc/vol11/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Literary Magazines at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The University of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Knowing the World: Shakespeare on Travel in As You Like It and Othello David Summers, Capital University etting to know the world through personal travel, particularly by means of the “semester abroad,” seems to G me to be one of the least controversial planks in the Humanities professors’ manifesto. However, reading Shakespeare with an eye toward determining his attitude toward travel creates a disjuncture between our conviction that travel generally, and studying abroad in particular, is an enriching experience, and Shakespeare’s tendency to hold the benefits of travel suspect. -

Chaotic Descriptor Table

Castle Oldskull Supplement CDT1: Chaotic Descriptor Table These ideas would require a few hours’ the players back to the temple of the more development to become truly useful, serpent people, I decide that she has some but I like the direction that things are going backstory. She’s an old jester-bard so I’d probably run with it. Maybe I’d even treasure hunter who got to the island by redesign dungeon level 4 to feature some magical means. This is simply because old gnome vaults and some deep gnome she’s so far from land and trade routes that lore too. I might even tie the whole it’s hard to justify any other reason for her situation to the gnome caves of C. S. Lewis, to be marooned here. She was captured by or the Nome King from L. Frank Baum’s the serpent people, who treated her as Ozma of Oz. Who knows? chattel, but she barely escaped. She’s delirious, trying to keep herself fed while she struggles to remember the command Example #13: word for her magical carpet. Malamhin of the Smooth Brow has some NPC in the Wilderness magical treasures, including a carpet of flying, a sword, some protection from serpents thingies (scrolls, amulets?) and a The PCs land on a deadly magical island of few other cool things. Talking to the PCs the serpent people, which they were meant and seeing their map will slowly bring her to explore years ago and the GM promptly back to her senses … and she wants forgot about it. -

Violence and the Sacred in Northern Ireland

VIOLENCE AND THE SACRED IN NORTHERN IRELAND Duncan Morrow University of Ulster at Jordanstown For 25 years Northern Ireland has been a society characterized not so much by violence as by an endemic fear of violence. At a purely statistical level the risk of death as a result of political violence in Belfast was always between three and ten times less than the risk of murder in major cities of the United States. Likewise, the risk of death as the result of traffic accidents in Northern Ireland has been, on average, twice as high as the risk of death by political killing (Belfast Telegraph, 23 January 1994). Nevertheless, the tidal flow of fear about political violence, sometimes higher and sometimes lower but always present, has been the consistent fundamental backdrop to public, and often private, life. This preeminence of fear is triggered by past and present circumstances and is projected onto the vision of the future. The experience that disorder is ever close at hand has resulted in an endemic insecurity which gives rise to the increasingly conscious desire for a new order, for scapegoats and for resolution. For a considerable period of time, Northern Ireland has actively sought and made scapegoats but such actions have been ineffective in bringing about the desired resolution to the crisis. They have led instead to a continuous mimetic crisis of both temporal and spatial dimensions. To have lived in Northern Ireland is to have lived in that unresolved crisis. Liberal democracy has provided the universal transcendence of Northern Ireland's political models. Northern Ireland is physically and spiritually close to the heartland of liberal democracy: it is geographically bound by Britain and Ireland, economically linked to Western Europe, and historically tied to emigration to the United States, Canada, and the South Pacific. -

The Great European Empires: British and Roman Rule Edward A

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 The Great European Empires: British and Roman Rule Edward A. Tomlinson Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tomlinson, Edward A., "The Great European Empires: British and Roman Rule" (2013). Honors Theses. 746. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/746 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Great European Empires: British and Roman Rule By Edward A. Tomlinson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History Union College June 2013 Tomlinson 1 Introduction: The greatest European imperial forces ever to exist were Rome and Britain. They controlled much of their known world and subjugated many foreign peoples to their rule. Rome ruled lands from India to the Atlantic Ocean, while Britain had colonies across the entire globe. The British Empire was at the height of its power in the Nineteenth Century, nearly 1200 years after the city of Rome was sacked by invading barbarian tribes. Even with more than a millennia passing between the fall of one empire and the rise of the other; they still shared many similarities in their manner of rule. They had to balance military might and political action to prevent rebellions and to maintain profitable colonies. -

De I'existencia Deis Iacetans

PYRENAE. núm. 35, vol. 2 (2004) ISSN: 0079-8215 (p. 7-29) REVISTA DE PREHISTÓRIA I ANTIGUITAT DE LA MEDITERRANIA OCCIDENTAL JOURNAL OF WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN PREHISTORY ANO ANTIQUITY De I'existencia deIs Iacetans ALFRED BROCH 1 GARCIA Departament d'Educació de la Generalitat de Catalunya el de Casp, 15, E-0801 OBarcelona [email protected] Les fonts grecollatines esmenten un poble anomenat lacetans. La manca absoluta de testimonis no literaris sobre ells ha generat un llarg i complex debat que, en lloc de contemplar la manca d'evidencia no escrita com una dada positiva, ha intentat generar reconstruccions de l'evidencia textual que puguin resoldre les diverses i greus contradiccions entre els textos. Pero si es dóna un tractament diferent a l'evidencia escrita (amb una analisi de recurrencia), se la vincula amb el conjunt d'evidencia coneguda sobre els antics pobles peninsulars i s'aplica una crítica estricta que posi en evidencia les mancances de les principals propostes de reconstrucció, cal concloure que la pretesa existencia real d'una etnia lacetana, no és sinó el resultat de la confusió (escrita) amb altres dues etnies que sí van existir i de les quals hi ha testimonis ferms: els laietans i els iace tans. PARAULES CLAU LAIETANS, LACETANS, IACETANS, PALETNOLOGIA, CULTURA IBERICA. The ancient sources about Iberia talk about the ancient people named Lacetanian. The absolute lack of any kind of non-literary evidence about them has incited a large and old polemic attemp ting to solve the various and deep contradictions contained in the literary corpus. A better way to study this case consists in changing this lack of evidence into a positive datum, making a dif ferent use of the literary evidence by developing a recurrence analysis inserted into a larger stock of evidence about the ancient Iberian peoples. -

Pagan Beliefs in <I>The Serpent's Tooth</I>

Volume 26 Number 1 Article 13 10-15-2007 Pagan Beliefs in The Serpent's Tooth Joe R. Christopher (emeritus) Tarleton State University, TX Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Christopher, Joe R. (2007) "Pagan Beliefs in The Serpent's Tooth," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 26 : No. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol26/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract An examination of the pagan belief structure in The Serpent’s Tooth, Diana Paxson’s retelling of King Lear. Discusses her use of source material in Shakespeare, Geoffrey of Monmouth, and early pagan religious beliefs. Additional Keywords Monmouth, Geoffer Mythlore y. Historia Regum Britanniae; Paganism in fantasy; Paxson, Diana. -

Gottheit (99) 1 Von 10

Gottheit (99) Suche Startseite Profil Konto Gottheit Zurück zu Witchways Diskussionsforum Themenübersicht Neues Thema beginnen Thema: Gottheit Thema löschen | Auf dieses Thema antworten Es werden die Beiträge 1 - 30 von 97 angezeigt. 1 2 3 4 Shannah Witchways Abnoba (keltische Muttergöttin) Abnoba war eine keltische Muttergöttin und personifizierte den Schwarzwald, welcher in der Antike den Namen Abnoba mons trug. Mythologie Sie galt als Beschützerin des Waldes, des Wildes und der Quellen, insbesondere als Schutzpatronin der Heilquellen in Badenweiler. Wild und Jäger unterstanden ihrem Schutz. Nach der bei der Interpretatio Romana üblichen Vorgehensweise wurde sie von den Römern mit Diana gleichgesetzt, wie etwa eine in Badenweiler aufgefundene Weiheinschrift eines gewissen Fronto beweist, der damit ein Gelübde einlöste. Wahrscheinlich stand auf dem Sockel, der diese Inschrift trägt, ursprünglich eine Statue dieser Gottheit. Ein in St. Georgen aufgefundenes Bildwerk an der Brigachquelle zeigt Abnoba mit einem Hasen, dem Symbol für Fruchtbarkeit, als Attribut. Tatsächlich wurden in Badenweiler auch Leiden kuriert, die zu ungewollter Kinderlosigkeit führten, und in den Thermen dieses Ortes war ungewöhnlicherweise die Frauenabteilung nicht kleiner als die für Männer. Abnoba dürfte für die Besucher von Badenweiler also vor allem als Fruchtbarkeitsgottheit gegolten haben. vor etwa einem Monat Beitrag löschen Shannah Witchways Aericura (keltische Totengottheit) Aericura ist eine keltisch-germanische Fruchtbarkeits- und Totengottheit. Mythologie Aericura, auch Aeracura, Herecura oder Erecura, ist eine antike keltisch-germanische (nach einigen Theorien jedoch ursprünglich sogar eine illyrische) Gottheit. Sie wird zumeist mit Attributen der Proserpina ähnlich dargestellt, manchmal in Begleitung eines Wolfs oder Hundes, häufig jedoch auch mit ruchtbarkeitsattributen wie Apfelkörben. Manchmal wird Aericura als Fruchtbarkeitsgottheit gedeutet, häufig jedoch eher als Totengöttin.