GEOCAP: Geothermal Capacity Building Program (Indonesia-Netherlands)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USGS Volcano Disaster Assistance Program in Indonesia

Final Report: Evaluation of the USAID/OFDA- USGS Volcano Disaster Assistance Program in Indonesia November 2012 This publication was produced at the request of the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared independently by International Business & Technical Consultants, Inc. (IBTCI). EVALUATION OF THE USAID/OFDA USGS VOLCANO DISASTER ASSISTANCE PROGRAM IN INDONESIA Contracted under RAN-I-00-09-00016-00, Task Order Number AID-OAA-TO-12-00038 Evaluation of the USAID/OFDA - USGS Volcano Disaster Assistance Program in Indonesia. Authors: Laine Berman, Ann von Briesen Lewis, John Lockwood, Erlinda Panisales, Joeni Hartanto Acknowledgements The evaluation team is grateful to many people in Washington DC, Vancouver, WA, Jakarta, Bandung, Jogjakarta, Tomohon, North Sulawesi and points in between. Special thanks to the administrative and support people who facilitated our extensive travels and the dedicated VDAP and CVGHM staff who work daily to help keep people safe. DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Evaluation of the USAID/OFDA- USGS Volcano Disaster Assistance Program in Indonesia TABLE OF CONTENTS GLOSSARY OF TERMS .................................................................................................................................. i ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... -

Indonesia Discovery

INDONESIA DISCOVERY Sample Itinerary INDONESIA DISCOVERY | OVERVIEW ITINERARY OVERVIEW INDONESIA DISCOVERY Jakarta, Bandung, Yogyakarta, Bromo, Kalibaru, Bali FEATURED Jakarta City EXPERIENCES Bogor Botanical Garden and Tea Plantation Tangkuban Perahu Crater Angklung – Traditional Bamboo Instrument Visit Kampung Naga, a Sundanese Village Dieng Crater Discover Arjuna Temple, Borobudur Temple and Prambanan Temple Explore Yogyakarta Malang City Tour Sunrise at Mount Bromo and Ride a Horse Kalibaru Village – Agricultural Heritage INDONESIA DISCOVERY | SAMPLE ITINERARY ITINERARY DAY 1 On arrival at Jakarta International Airport you will be met with our guide and then transfer to hotel. Jakarta, the Capital, is the largest city. It is located on the north- ARRIVAL JAKARTA western coast of the island of Java. Jakarta is the country economic, cultural and political center. It is the most populous city in Indonesia. Jakarta city as the biggest city and most developed city in Indonesia has long history and offers old heritage or historical places traditional activity up to modern recreation and entertainment. DAY 2 In the morning your guide will pick you up from your hotel and start the overland journey to visit Bogor. Drive to Bogor is about 1,5 hours, you’ll begin with visit the beautiful BOGOR BOTANICAL GARDEN & town of Bogor located at the site one of the world’s most outstanding botanical TEA PLANTATION gardens. The Bogor Botanical Gardens host more than 15.000 species of trees and plants and over 5.000 species of tropical orchid. Spend time walking around the gardens and enjoying the beautiful landscapes. From the Garden can be seen Bogor’s Presidential Palace, which is noted for its distinctive architecture. -

Furthering the Investigation of Eruption Styles Through Quantitative Shape Analyses of Volcanic Ash Particles

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Furthering the investigation of eruption styles through quantitative shape analyses of volcanic ash particles Nurfiani, Dini; Bouvet de Maisonneuve, Caroline 2018 Nurfiani, D., & Bouvet de Maisonneuve, C. (2018). Furthering the investigation of eruption styles through quantitative shape analyses of volcanic ash particles. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 354102‑114. doi: https://hdl.handle.net/10356/88325 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2017.12.001 © 2017 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CCBY‑NC‑ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by‑nc‑nd/4.0/). Downloaded on 01 Oct 2021 04:27:10 SGT Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 354 (2018) 102–114 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jvolgeores Furthering the investigation of eruption styles through quantitative shape analyses of volcanic ash particles D. Nurfiani ⁎, C. Bouvet de Maisonneuve Earth Observatory of Singapore, Nanyang Technological University, 639798, Singapore article info abstract Article history: Volcanic ash morphology has been quantitatively investigated for various aims such as studying the settling Received 21 June 2017 velocity of ash for modelling purposes and understanding the fragmentation processes at the origin of explosive Received in revised form 30 November 2017 eruptions. In an attempt to investigate the usefulness of ash morphometry for monitoring purposes, we analyzed Accepted 1 December 2017 the shape of volcanic ash particles through a combination of (1) traditional shape descriptors such as solidity, Available online 5 December 2017 convexity, axial ratio and form factor and (2) fractal analysis using the Euclidean Distance transform (EDT) Keywords: method. -

Ilmu Quran Dan Tafsir (Iqt)

SEKOLAH TINGGI AGAMA ISLAM PERSIS BANDUNG Jl. Ciganitri No 2 Cipagalo Bojongsoang Bandung Phone 022-7563521 MAHASISWA ILMU QURAN TAFSIR (IQT) ANGKATAN 2015 NO NAMA MAHASISWA NIM ASAL SEKOLAH ALAMAT MA Persis 1 Agus Faisal Ahmad 15.01.0827 Komp. Griya Sukasari Rt. 01/18 Ds. Ciwidey Kec. Ciwidey Cikoneng 2 Alfi Nadia 15.01.0839 MA Assalam Parakan Waas Kec. Batununggal Komp. GBA II Blok J5 No. 34 Rt. 02/03 Ds. Cipagalo Kec. 3 Amirul Muttaqien 15.01.0823 MA Ciganitri Bojongsoang MA Persis Jl. Suryani Dalam 4 Rt. 06/02 Ds. Warung Muncang Kec. Bandung 4 Asep Abdul Wahid 15.01.0816 Pajagalan Kulon Kota Bandung 5 Asep Rustandi 15.01.0820 SMK Ganesha Kp. Curug Dogdog Rt. 06/10 Ds. Sukamenak Kec.Margahayu 6 Deni Sonjaya 15.01.0826 STM Tubun Babatan No. 2 Kel. Kebonjeruk Kec. Andir 7 Endang Al-Anshari 15.01.0840 Paket C Citamiang Rt. 3/7 Ds. Cangkuang Kulon Kec. Dayeuhkolot Komplek Bumi Asri Rt. 007/008 Ds. Genpolsari Kec. Bandung 8 Endang Rohiman Hidayat 15.01.0845 SMEA Pasundan Kulon Komp. Sapta Taruna PU Rt. 05/08 Ds. Kujang sari Bandung Kidul 9 Euis Nani Rusmawati Suryana 15.01.0814 Kota Bandung Kp. Pagarsih Rt. 3/1 Ds. Babakan Tarogong Kec. Bojongloa Kaler 10 Eva Septiana 15.01.0813 MA Kota Bandung Jl. Kopo Gg Lapang 1 Rt. 09/04 Ds. Kopo Kec. Bojongloa Kaler Kota 11 Fanny Ilaila Khoirun-Nisa 15.01.0812 MA Bandung 12 Farhan Ahsan Anshari 15.01.0843 Perum Pangulah Permai Rt.1/9 Ds. -

Potensi Dan Wilayah Kerja Pertambangan Panas Bumi Di Indonesia

POTENSI DAN WILAYAH KERJA PERTAMBANGAN PANAS BUMI DI INDONESIA Oleh: Rina Wahyuningsih SUBDIT PANAS BUMI ABSTRACT There are 252 geothermal locations have been identified that distributed along a volcanic belt extending from Sumatera, Java, Nusa Tenggara, Sulawesi until Maluku. Having total potential of 27 GWe, puts Indonesia as the biggest geothermal potential country in the world. By depleting of fossil fuel in Indonesia, geothermal energy seems to be a favorable alternative energy to fulfill domestic energy demand The Geothermal Law that issued in 2003 is expected to give a conducive atmosphere in geothermal development in Indonesia. To speed up the investments in geothermal energy, it is important to provide information about geothermal working area that can be developed. Besides 33 Geothermal Working Area that has been issued, 28 open geothermal working areas have been suggested with total potential of about 13.000 MWe. This energy potential is expected to fulfill the geothermal development target to generate electricity of 6000 MWe in 2020. SARI Sebanyak 252 lokasi panas bumi di Indonesia tersebar mengikuti jalur pembentukan gunung api yang membentang dari Sumatra, Jawa, Nusa Tenggara, Sulawesi sampai Maluku. Dengan total potensi sekitar 27 GWe, Indonesia merupakan negara dengan potensi energi panas bumi terbesar di dunia. Sebagai energi terbarukan dan ramah lingkungan, potensi energi panas bumi yang besar ini perlu ditingkatkan kontribusinya untuk mencukupi kebutuhan energi domestik yang akan dapat mengurangi ketergantungan Indonesia terhadap sumber energi fosil yang semakin menipis. Dengan adanya UU No. 27 Tahun 2003 Tentang Panas Bumi diharapkan akan memberikan kepastian hukum dalam pengembangan panas bumi di Indonesia. Untuk mempercepat investasi di bidang panas bumi, perlu disiapkan informasi mengenai Wilayah Kerja Pertambangan (WKP) panas bumi yang dapat dikembangkan. -

Bab I Pendahuluan

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Indonesia merupakan negara kepulauan terbesar di dunia, terletak di utara Australia dan selatan Filipina dan di kawasan Asia Tenggara, Citra satelit analisis yang dilakukan di awal 2000-an, mengungkapkan bahwa Indonesia memiliki 18,108 pulau. Indonesia terletak di kawasan ring of fire dan memiliki 400 gunung berapi, dimana terdapat 129 gunung berapi yang masih aktif. Gunung adalah suatu bentuk permukaan tanah yang menjulang yang letaknya jauh lebih tinggi daripada tanah-tanah di daerah sekitarnya. Gunung pada umumnya lebih besar dibandingkan dengan bukit. Gunung pada umumnya memiliki lereng yang curam dan tajam dan berbatuan (Erfurt-Cooper et al., 2015). Pada awalnya aktivitas pariwisata di sebuah pegunungan masih termasuk kategori geotourism. Lalu perkembangan pariwisata gunung berapi berubah menjadi volcano tourism pada abad ke-18 dan berevolusi dari wisata yang hanya untuk kalangan elit menjadi pariwisata massal untuk siapa saja seperti hari ini dan menjadi salah satu sektor paling penting dari geotourism. Volcano tourism digambarkan sebagai tempat wisata yang menghasilkan keuntungan ekonomi dan berdasar pada sebuah gunung. Volcano tourism memberikan kesempatan untuk mendapatkan keuntungan ekonomi tanpa melihat perubahan musim dan iklim (Erfurt-Cooper et al., 2015). Gunung berapi dibedakan dalam 1 2 tiga kategori berdasarkan sejarah letusannya, yaitu gunung api tipe A, tipe B, dan tipe C. Gunung api tipe A tercatat pernah meletus sejak 1600, jumlahnya 79. Tipe B adalah gunung api yang mempunyai kawah dan lapangan solfatara/fumarola tapi tidak ada sejarah letusan sejak tahun 1600, jumlahnya 29. Gunung api tipe C hanya berupa lapangan solfatara/fumarola, dengan jumlah 21 gunung api (Erfurt-Cooper et al., 2015). -

WGC 2010 Preliminary Questionnaire WGC 2010

10 010 0 C 20 WGC 2 C 201 WG ress ire WG ess Cong nna ongr rmal estio mal C othe ary Qu other ld Ge imin ld Ge Wor Prel WORLD Wor GEOTHERMAL CONGRESS 2010 Bali, Indonesia 25-29 April, 2010 Mailing Address: Organizing Committee of WGC2010 Secretariat API/INAGA: Gedung Indonesia Power Lt.1Jl. Jend. Gatot Subroto Kav.18, Jakarta 12950, Indonesia Phone: +62.21.5253787, +62.21.5252379; Fax : +62.21.5255939 First Announcement General Information 25 – 29 April, 2010 – BICC Nusa Name: Dua Bali, Indonesia AN EXTENSIVE CULTURAL AND SOCIAL PROGRAM IS BEING PLANNED Tittle: Organization: ACCOMPANYING PERSONS PROGRAM WILL ALSO BE PROVIDED Mailing Address: BALI DECLARATION City: Country: Zip: At the closing ceremony of the WGC 2010 the Bali Declaration Telp: Fax: empowering international geothermal development will be announced. Title of proposed paper(s) for the Congress: IMPORTANT DATES June 30th, 2008 : Call for abstracts January 31st, 2009 : Abstract deadline March 31st, 2009 : Notification of acceptance of abstracts Field trips I am interested in participating in the following field trips: May 31st , 2009 : Draft papers due Bali ( 2 days Pre Congress Tour) October 30th, 2009 : Final paper due Bali and Bedugul Field on Bali (2 days Post Congress Trips) April 25-29th, 2010 : WGC 2010 Yogyakarta and Dieng Field on Central Java (3 Days Post Congress Trips) Jakarta and Salak Field on West Java (3 Days Post Congress Trips) FIRST ANNOUNCEMENT RESPONSE Bandung and Kamojang-Wayang Windu Field on West Java (3 Days Post Bali, Indonesia Congress Trips) 25-29 April 2010 Please return the attached questionnaire by mail, fax or e-mail or go to website www.wgc2010.org and join the mailing list. -

Java Rail Tour 30Mar-16Apr 19

ACROSS JAVA BY RAIL 30th March - 16th April 2019 ESCORTED BY Bob Daniel EXPLORE THE GARDEN OF THE EAST HIGHLIGHTS Jakarta to Ubud over 18 days You will travel with no more than 20 passengers on this tour experiencing a variety of modes of transport from a bullock cart ride to becaks. There are 3 chartered steam train excursions and you will be staying in 4 to 5 star properties. You will visit smouldering volcanoes, feast on local delicacies, enjoy traditional dance performances, travel through spice plantations, be guided through UNESCO World Heritage sites and experience the warmth and hospitality of the locals. YOUR LEADER Bob Daniel An Indonesian expert, a rail enthusiast and an accomplished tour leader, Bob will have you laughing and learning your way across Java, "The Garden Of The East". His credentials include owning a travel company for over 40 years, regularly volunteering on rail projects, and attending global travel marts to keep him educated with latest trends, you are in great hands, EXPLORE THE GARDEN OF THE EAST VISITING Jakarta – Taman Mini Indonesia Indah – Bandung Tangkuban Perahu – Yogyakarta Prambanan – Bugisan Village – Borobudur – Losari – Ambarawa – Solo – Madiun – Malang – Bromo – Jember – Kalibaru – Ketapang – Banyuwangi – Gilimanuk – Ubud INCLUDING 17 nights in centrally located 4&5 star hotels – breakfast daily – 15 lunches – 3 dinners – transport throughout the tour – entrance fees & excursions – local expert guides – tipping – Australian tour leader EXPERIENCING Tropical gardens - many museums including the National Museum of Indonesia & Ambarawa Railway Museum - MONAS and Istiqlal Mosque - 150 hectare park - hot springs - the UNESCO World Heritage site of Prambanan - Borobudur, the famous Buddhist temple - MesaStila coffee plantation - Malang tour with its many grand colonial-era buildings - 4WD jeep to Mt Bromo - COSTING Bali's iconic Ulun Danu Beratan - lots of train journeys - much much more! AUD $5,495 pp twin share. -

Research Article Study of Hybrid Neurofuzzy Inference System for Forecasting Flood Event Vulnerability in Indonesia

Hindawi Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience Volume 2019, Article ID 6203510, 13 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6203510 Research Article Study of Hybrid Neurofuzzy Inference System for Forecasting Flood Event Vulnerability in Indonesia Sri Supatmi ,1,2 Rongtao Hou ,1 and Irfan Dwiguna Sumitra 3 1School of Computer and Software, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, No. 219 Ningliu Road, Pukou, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210044, China 2Computer Engineering Department, Universitas Komputer Indonesia, No. 102-116 Dipati Ukur, Bandung, West Java 40132, Indonesia 3Postgraduate of Information System Department, Universitas Komputer Indonesia, No. 102-116 Dipati Ukur, Bandung, West Java 40132, Indonesia Correspondence should be addressed to Sri Supatmi; [email protected] Received 18 October 2018; Accepted 15 January 2019; Published 25 February 2019 Academic Editor: Carmen De Maio Copyright © 2019 Sri Supatmi et al. )is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. An experimental investigation was conducted to explore the fundamental difference among the Mamdani fuzzy inference system (FIS), Takagi–Sugeno FIS, and the proposed flood forecasting model, known as hybrid neurofuzzy inference system (HN-FIS). )e study aims finding which approach gives the best performance for forecasting flood vulnerability. Due to the importance of forecasting flood event vulnerability, the Mamdani FIS, Sugeno FIS, and proposed models are compared using trapezoidal-type membership functions (MFs). )e fuzzy inference systems and proposed model were used to predict the data time series from 2008 to 2012 for 31 subdistricts in Bandung, West Java Province, Indonesia. -

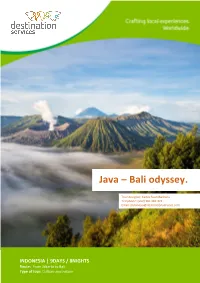

Java – Bali Odyssey

Java – Bali odyssey. Tour designer: Kadek Suardhamana Telephone: (+62) 361 282 474 Email: [email protected] INDONESIA | 9DAYS / 8NIGHTS Route: From Jakarta to Bali Type of tour: Culture and nature 1 TOUR OVERVIEW Immerse yourself in the real Java, discovering one of the world’s most beautiful islands and its friendly people before crossing to Bali. This breathtaking nine-day tour takes you to most famous sights and attractions in the island. Starting in the capital, Jakarta, in the north-west, travel through the heart of Java to visit Prambanan, Borobudur and Mount Bromo – where an otherworldly lunar landscape of volcanoes emerges from fields of dried-up lava – and on to Ijen in the east. The odyssey ends in Bali, after a ferry journey across the strait dividing the two islands. TOUR HIGHLIGHTS Jakarta: Enjoy a panoramic tour of the capital, seeing sights such as the National Museum, old harbour and more Bandung: A city famed for its art deco architecture and the nearby Tangkuban Perahu Ciater hot springs Prambanan: Reconstructed ninth century Hindu temple boasting beautiful and elaborate carvings Yogyakarta: Visit the city’s two palaces – the Sultan’s and the Water – and explore the historic Kotagede district Borobudur: Imposing and beautiful Buddhist temple that is a UNESCO World Heritage Site Solo: This green city is home to the magnificent Mangkunegaran Palace Mount Bromo: Experience sunrise over this smouldering and growling volcanic caldera Ijen: Trek for more than an hour to enjoy another sunrise experience over -

By the End of This Lesson, You Will Be Able To: Describe Types of Tourist

By the end of this lesson, you will be able to: ✓ Describe types of tourist attractions ✓ Use adjectives to describe tourist attractions From Sabang to Merauke, we have a lot of tourist attractions in Indonesia. Do you know the types of these famous attractions below? Monu ment Temple Traditional Houses Amusement Park On the previous exercise, we have some types of tourist attraction in Indonesia. Although there are many types of tourist attractions in the world, in Indonesia, the typical ones would be: places of natural beauty, monuments, temples, religious heritage, and traditional houses. Refer to the following table about types of tourist attraction and some example of the places: Types of Tourist Example of The Places Attraction Temple Prambanan, Borobudur Monument National Monument, Yogya Kembali Monument Theme Park TMII, Ancol Dreamland National Park Way Kambas, Siberut, Bunaken Palace Ubud Royal Palace, Maimun Palace Castle Vredeburg, Fort de Kock , Fort Speelwijk Mosque The Grand Istiqlal, The Golden Dome Mosque Cathedral Maria Annai Velangkanni, Notre Dame Zoo Ragunan, Safari Park Mountain Tangkuban Perahu, Bromo Beach Kuta, Legian, Seminyak Waterfall Saluopa waterfall, The Waterfall of Two Colours Lake Toba, Segara Anak, Kelimutu As a maritime country with more than 17.000 island in total, we are known with our beautiful tropical views. Here is what Banu, a local tourist guide, said about where he’s from, Lombok: Hello, everyone! My name is Banu. I live in a very beautiful island called Lombok. It is a nearby island of Bali. Along the island, there are picturesque beaches such as Kuta Lombok, Tanjung Aan, Selong Belanak, and Mawon. -

Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) 7 Eruptions and Their Chilling Impacts GEOSPHERE; V

Research Paper THEMED ISSUE: Subduction Top to Bottom 2 GEOSPHERE Anticipating future Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) 7 eruptions and their chilling impacts GEOSPHERE; v. 14, no. 2 Chris Newhall1, Stephen Self2, and Alan Robock3 1Mirisbiris Garden and Nature Center, Sitio Mirisbiris, Barangay Salvacion, Santo Domingo, Albay 4508, Philippines doi:10.1130/GES01513.1 2Department of Earth & Planetary Science, University of California, 307 McCone Hall, Berkeley, California 94720-4767, USA 3Department of Environmental Sciences, Rutgers University, 14 College Farm Road, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901, USA 7 figures; 3 tables CORRESPONDENCE: cgnewhall@ gmail .com ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION CITATION: Newhall, C., Self, S., and Robock, A., 2018, Worst-case or high-end subduction-related earthquakes and tsunamis Explosive volcanic eruptions occur in a wide range of sizes, and the mod- Anticipating future Volcanic Explosivity Index (VEI) 7 eruptions and their chilling impacts: Geosphere, v. 14, of 2004 and 2011 are painfully fresh in our memories. High-end subduction- ern world has not yet seen an eruption of either Volcanic Explosivity Index no. 2, p. 1–32, doi:10.1130/GES01513.1. related volcanic eruptions have not occurred in recent memory, so we review (VEI) 7 or 8, the highest 2 orders of magnitude known from written and geo- historical and geologic evidence about such eruptions that will surely recur logic history (Newhall and Self, 1982; Mason et al., 2004; Global Volcanism Science Editor: Shanaka de Silva within coming centuries. Specifically, we focus on Volcanic Explosivity Index Program, 2013). Most, although not all, of these very large eruptions have oc- Guest Associate Editor: Robert Stern (VEI) 7 eruptions, which occur 1–2 times per thousand years.