Hotel California: Housing the Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song Artist 25 Or 6 to 4 Chicago 5 Years Time Noah and the Whale A

A B 1 Song Artist 2 25 or 6 to 4 Chicago 3 5 Years Time Noah and the Whale 4 A Horse with No Name America 5 Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus 6 Adelaide Old 97's 7 Adelaide 8 Africa Bamba Santana 9 Against the Wind Bob Seeger 10 Ain't to Proud to Beg The Temptations 11 All Along the W…. Dylan/ Hendrix 12 Back in Black ACDC 13 Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce 14 Bad Moon Risin' CCR 15 Bad to the Bone George Thorogood 16 Bamboleo Gipsy Kings 17 Black Horse and… KT Tunstall 18 Born to be Wild Steelers Wheels 19 Brain Stew Green Day 20 Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison 21 Chasing Cars Snow Patrol 22 Cheesburger in Para… Jimmy Buffett 23 Clocks Coldplay 24 Close to You JLS 25 Close to You 26 Come as you Are Nirvana 27 Dead Flowers Rolling Stones 28 Down on the Corner CCR 29 Drift Away Dobie Gray 30 Duende Gipsy Kings 31 Dust in the Wind Kansas 32 El Condor Pasa Simon and Garfunkle 33 Every Breath You Take Sting 34 Evil Ways Santana 35 Fire Bruce Springsteen Pointer Sis.. 36 Fire and Rain James Taylor A B 37 Firework Katy Perry 38 For What it's Worth Buffalo Springfield 39 Forgiveness Collective Soul 40 Free Bird Lynyrd Skynyrd 41 Free Fallin Tom Petty 42 Give me One Reason Tracy Chapman 43 Gloria Van Morrison 44 Good Riddance Green Day 45 Have You Ever Seen… CCR 46 Heaven Los Lonely Boys 47 Hey Joe Hendrix 48 Hey Ya! Outcast 49 Honkytonk Woman Rolling Stones 50 Hotel California Eagles 51 Hotel California 52 Hotel California Eagles 53 Hotel California 54 I Won't Back Down Tom Petty 55 I'll Be Missing You Puff Daddy 56 Iko Iko Dr. -

The Case of Toronto ⁎ Martine Augusta, Alan Walksb, a Edward J

Geoforum 89 (2018) 124–136 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geoforum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geoforum Gentrification, suburban decline, and the financialization of multi-family T rental housing: The case of Toronto ⁎ Martine Augusta, Alan Walksb, a Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA b Department of Geography, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5S-3G3, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: While traditional forms of gentrification involved the conversion of rental units to owner-occupation, a new Financialization rental-tenure form of gentrification has emerged across the globe. This is driven by financialization, reduced Apartments tenant protections, and declining social-housing production, and is characterized by the replacement of poorer REITs renters with higher-income tenants. Many poorer renters are in turn being displaced out of the inner city and into Inequality older suburban neighbourhoods where aging apartment towers had provided a last bastion of affordable Gentrification accommodation, but which are now also targeted by large rental housing corporations. These dynamics are Suburban decline increasingly dominated by what we call ‘financialized landlords,’ including those owned or run by private equity funds, financial asset management corporations, and real estate investment trusts (REITS). Such firms float securities on domestic and international markets and use the proceeds to purchase older rental buildings charging affordable rents, and then apply a range of business strategies to extract value from the buildings, existing tenants and local neighbourhoods, and flow them to investors. This paper documents this process in Toronto, Canada's largest city and a city experiencing both sustained gentrification and advanced suburban restructuring. -

Earnest 1 the Current State of Economic Development in South

Earnest 1 The Current State of Economic Development in South Los Angeles: A Post-Redevelopment Snapshot of the City’s 9th District Gregory Earnest Senior Comprehensive Project, Urban Environmental Policy Professor Matsuoka and Shamasunder March 21, 2014 Earnest 2 Table of Contents Abstract:…………………………………………………………………………………..4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………….5 Literature Review What is Economic Development …………………………………………………………5 Urban Renewal: Housing Act of 1949 Area Redevelopment Act of 1961 Community Economic Development…………………………………………...…………12 Dudley Street Initiative Gaps in Literature………………………………………………………………………….14 Methodology………………………………………………………………………………15 The 9th Council District of Los Angeles…………………………………………………..17 Demographics……………………………………………………………………..17 Geography……………………………………………………………………….…..19 9th District Politics and Redistricting…………………………………………………23 California’s Community Development Agency……………………………………………24 Tax Increment Financing……………………………………………………………. 27 ABX1 26: The End of Redevelopment Agencies……………………………………..29 The Community Redevelopment Agency in South Los Angeles……………………………32 Political Leadership……………………………………………………………34 Case Study: Goodyear Industrial Tract Redevelopment…………………………………36 Case Study: The Juanita Tate Marketplace in South LA………………………………39 Case Study: Dunbar Hotel………………………………………………………………46 Challenges to Development……………………………………………………………56 Loss of Community Redevelopment Agencies………………………………..56 Negative Perception of South Los Angeles……………………………………57 Earnest 3 Misdirected Investments -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Full Report Introduction to Project

THE ILLUSION OF CHOICE: Evictions and Profit in North Minneapolis Author: Principal Investigator, Dr. Brittany Lewis, Senior Research Associate Contributing Authors: Molly Calhoun, Cynthia Matthias, Kya Conception, Thalya Reyes, Carolyn Szczepanski, Gabriela Norton, Eleanor Noble, and Giselle Tisdale Artist-in-Residence: Nikki McComb, Art Is My Weapon “I think that it definitely has to be made a law that a UD should not go on a person’s name until after you have been found guilty in court. It is horrific that you would sit up here and have a UD on my name that prevents me from moving...You would rather a person be home- less than to give them a day in court to be heard first...You shouldn’t have to be home- less to be heard.” – Biracial, female, 36 years old “I’ve heard bad “There is a fear premium attached to North Min- things. He’s known neapolis. Because what’s the stereotypical image as a slumlord...But people have of North Minneapolis? I could tell you. against my better Bang, bang. People are afraid of it. If you tell people, judgment, to not I bought a property in North Minneapolis. What they wanting to be out say is, ‘Why would you do that?’” – White, male, a place and home- 58 year old, property manager and owner less and between moving, I took the first thing. It was like a desper- ate situation.” – Biracial, female, 45 years old For more visit z.umn.edu/evictions PURPOSE, SELECT LITERATURE REVIEW, RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS Purpose Single Black mothers face the highest risk of eviction in the Single Black women with children living below the poverty line United States. -

All Securities Law, Franchise Law, and Take-Over Law Filings for 3/28/2021 Through 4/3/2021

All Securities Law, Franchise Law, and Take-Over Law Filings for 3/28/2021 through 4/3/2021 Securities Law Registration Filings Made with DFI’s Securities Division Firm Name Location Date File Number Status Received Capital Impact Partners Arlington, VA 3/30/2021 863527-02 Registered Number of Registration Filings: 1 Securities Law Exemption Filings Made with DFI’s Securities Division Firm Name Location Date File Number Status Received Life Point Christian Fellowship San Tan Valley, 3/31/2021 863617-08 Not Disallowed D/B/A Lifepoint Church AZ Number of Exemption Filings: 1 Securities Law Federal Covered Security-Investment Company Filings Made with DFI’s Securities Division Firm Name Location Date File Number Status Received AMG Funds III AMG GW&K High Greenwich, CT 4/2/2021 863525-03 Filed Income Fund Class I Ei. Ventures, Inc. Kihei, HI 4/2/2021 863624-25 Filed Epilog Imaging Systems, Inc. San Jose, CA 4/2/2021 863623-25 Filed 1WS Credit Income Fund Class New York, NY 4/1/2021 863521-59 Filed A-2 Shares Advisors Series Trust First Milwaukee, WI 4/1/2021 863520-03 Filed Sentier American Listed Infrastructure Fund Class I FS Series Trust FS Real Asset Philadelphia, PA 4/1/2021 863523-03 Filed Fund Class A FS Series Trust FS Real Asset Philadelphia, PA 4/1/2021 863524-03 Filed Fund Class I Morgan Stanley Institutional New York, NY 4/1/2021 863522-03 Filed Fund, Inc. Emerging Markets Leaders Portfolio Class IR Aspiriant Risk-Managed Capital Milwaukee, WI 3/30/2021 863622-59 Filed Appreciation Fund Aspiriant Risk-Managed Real Milwaukee, -

The Dunbar Hotel and the Golden Age of L.A.’S ‘Little Harlem’

SOURCE C Meares, Hadley (2015). When Central Avenue Swung: The Dunbar Hotel and the Golden Age of L.A.’s ‘Little Harlem’. Dr. John Somerville was raised in Jamaica. DEFINITIONS When he arrived in California in 1902, he was internal: people, actions, and shocked by the lack of accommodations for institutions from or established by people of color on the West Coast. Black community members travelers usually stayed with friends or relatives. Regardless of income, unlucky travelers usually external: people, actions, and had to room in "colored boarding houses" that institutions not from or established by were often dirty and unsafe. "In those places, community members we didn't compare niceness. We compared badness," Somerville's colleague, Dr. H. Claude Hudson remembered. "The bedbugs ate you up." Undeterred by the segregation and racism that surrounded him, Somerville was the first black man to graduate from the USC dental school. In 1912, he married Vada Watson, the first black woman to graduate from USC's dental school. By 1928, the Somervilles were a power couple — successful dentists, developers, tireless advocates for black Angelenos, and the founders of the L.A. chapter of the NAACP. As the Great Migration brought more black people to L.A., the city cordoned them off into the neighborhood surrounding Central Avenue. Despite boasting a large population of middle and upper class black families, there were still no first class hotels in Los Angeles that would accept blacks. In 1928, the Somervilles and other civic leaders sought to change all that. Somerville "entered a quarter million dollar indebtedness" and bought a corner lot at 42nd and Central. -

Major Hotel Chains Session Objectives

MAJOR HOTEL CHAINS SESSION OBJECTIVES After the end of the session one should be able to understand the Major hotel chains of the world & their history of origin. CONTENT LEADING HOTEL CHAINS HISTORY OF TAJ, ITC & THE OBEROI GROUPS LEADING HOTEL CHAINS Hyatt JW Marriott Hotels InterContinental Hotels Le Méridien Radisson Hotels LEADING HOTEL CHAINS Accor (Sofitel, Novotel) Choice Hotels (Clarion Hotels, Comfort, Quality) Crowne Plaza Hotels & Resorts Fairmont Hotels & Resorts LEADING HOTEL CHAINS IN INDIA Taj Group of Hotels The Oberoi Group of Hotels Park Group of Hotels LEADING HOTEL CHAINS IN INDIA Kenilworth Group of Hotels Welcome Group of Hotels The Lalit Group Clarks Group TAJ HOTELS, RESORTS AND PALACES Taj Hotels, Resorts and Palaces, is the largest Indian luxury hotel chain. A wholly owned subsidiary of the Tata Group, Taj Hotels Resort and Palaces comprises 77 hotels in 39 locations across India. In addition to this there are 18 International Hotels; in various countries. HISTORY The Indian Hotels Company was founded in 1897. Their first and most well known property is the Taj Mahal Palace in Colaba, Mumbai It was opened in December 16, 1903, by the founder of the Tata Group, Jamshedji Nusserwanji Tata with a total of seventeen guests. In 1971, the 220 room Taj Mahal Hotel was converted into a 325 roomed multistoried hotel. OBEROI HOTELS Oberoi Hotels & Resorts are the epitome of luxury and hospitality Exquisite interiors, impeccable service, fine cuisine and contemporary technology come together to create an experience that is both grand and intimate Founded in 1934, the group owns and manages award winning luxury hotels and cruisers in India, Egypt, Indonesia, Mauritius and Saudi Arabia The Oberoi Hotels are known to own some of the grandest properties in Asia THE STORY OF M.S OBEROI Rai Bahadur Mohan Singh Oberoi (August 15, 1898—May 3, 2002) was a renowned Indian hotelier widely regarded as the father of 20th century India's hotel business. -

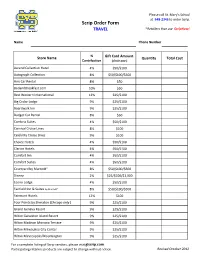

Scrip Order Forms October 2012.Xlsx

Please call St. Mary's School at 548-2345 to order Scrip. Scrip Order Form TRAVEL *Retailers that use ScripNow! Name Phone Number % Gift Card Amount Store Name Quantity Total Cost Contribution (circle one ) Ascend Collection Hotel 4% $50/$100 Autograph Collection 8% $50/$100/$500 Avis Car Rental 8% $50 BedandBreakfast.com 10% $50 Best Western International 12% $25/$100 Big Cedar Lodge 9% $25/$100 Boardwalk Inn 9% $25/$100 Budget Car Rental 8% $50 Cambria Suites 4% $50/$100 Carnival Cruise Lines 8% $100 Celebrity Cruise Lines 9% $100 Choice Hotels 4% $50/$100 Clarion Hotels 4% $50/$100 Comfort Inn 4% $50/$100 Comfort Suites 4% $50/$100 Courtyard by Marriott* 8% $50/$100/$500 Disney 2% $25/$100/$1,000 Econo Lodge 4% $50/$100 Fairfield Inn & Suites by Marriott* 8% $50/$100/$500 Fairmont Hotels 12% $100 Four Points by Sheraton (Chicago only ) 9% $25/$100 Grand Geneva Resort 9% $25/$100 Hilton Galveston Island Resort 9% $25/$100 Hilton Madison Monona Terrace 9% $25/$100 Hilton Milwaukee City Center 9% $25/$100 Hilton Minneapolis/Bloomington 9% $25/$100 For a complete listing of Scrip vendors, please visit glscrip.com. Participating retailers products are subject to change without notice. Revised October 2012 Please call St. Mary's School at 548-2345 to order Scrip. Scrip Order Form TRAVEL *Retailers that use ScripNow! Name Phone Number % Gift Card Amount Store Name Quantity Total Cost Contribution (circle one ) Holiday Inn on the Beach (Galveston, TX ) 9% $25/$100 Hotel Phillips 9% $25/$100 Hyatt Hotels* 9% $50/$100 Hyatt Place 9% $50/$100 -

![The Spirit of Event Business Events by Marriott: the Standard for Consistently Successful Events [ Sustainable Support for Your Event Management ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3094/the-spirit-of-event-business-events-by-marriott-the-standard-for-consistently-successful-events-sustainable-support-for-your-event-management-583094.webp)

The Spirit of Event Business Events by Marriott: the Standard for Consistently Successful Events [ Sustainable Support for Your Event Management ]

the spirit of event business Events by Marriott: the standard for consistently successful events [ Sustainable support for your event management ] Fresh ideas – perfect events With more than 3,500 hotels in over 70 Discover the essence of Events by Marriott. Reliability also needs a constant flow of countries, Marriott International isn’t just The unique sum of six simple promises fresh ideas. Our meetings and events one of the most successful hotel corpora- that reflect our understanding of your needs include products, practices and services tions; it’s also one of the largest and most as an event planner, matured over the that reduce overall environmental impact. experienced hosts of meetings and events course of decades. This means you can rely on a perfect event around the world. That’s reason enough to The uniform standards of the hotels in that also benefits the environment. combine all of our experience and know- Europe of JW Marriott®, Renaissance® ledge in a meetings and events programme Hotels and Marriott® Hotels & Resorts which assures you a product consistency ensure that the success of each of your and service security that is unrivalled: events can be planned. EVENTS by MARRIOTT the spirit of event business. Strong brands – a clear vision: continously successful events through consistent service JW Marriott Renaissance Hotels Marriott Hotels & Resorts A brand that offers you uncompromising, The brand that guarantees a pleasant The brand that inspires and caters to the understated luxury in a pleasant environ- stay for discerning guests, with lots ambitious guest can be found at more ment at over 40 exclusive city and resort of little touches. -

Brown V. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society

Brown v. Topeka Board of Education Oral History Collection at the Kansas State Historical Society Manuscript Collection No. 251 Audio/Visual Collection No. 13 Finding aid prepared by Letha E. Johnson This collection consists of three sets of interviews. Hallmark Cards Inc. and the Shawnee County Historical Society funded the first set of interviews. The second set of interviews was funded through grants obtained by the Kansas State Historical Society and the Brown Foundation for Educational Excellence, Equity, and Research. The final set of interviews was funded in part by the National Park Service and the Kansas Humanities Council. KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Topeka, Kansas 2000 Contact Reference staff Information Library & archives division Center for Historical Research KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 6425 SW 6th Av. Topeka, Kansas 66615-1099 (785) 272-8681, ext. 117 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.kshs.org ©2001 Kansas State Historical Society Brown Vs. Topeka Board of Education at the Kansas State Historical Society Last update: 19 January 2017 CONTENTS OF THIS FINDING AID 1 DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION ...................................................................... Page 1 1.1 Repository ................................................................................................. Page 1 1.2 Title ............................................................................................................ Page 1 1.3 Dates ........................................................................................................ -

Race, Housing and the Fight for Civil Rights in Los Angeles

RACE, HOUSING AND THE FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS IN LOS ANGELES Lesson Plan CONTENTS: 1. Overview 2. Central Historical Question 3. Extended Warm-Up 4. Historical Background 5. Map Activity 6. Historical Background 7. Map Activity 8. Discriminatory Housing Practices And School Segregation 9. Did They Get What They Wanted, But Lose What They Had? 10. Images 11. Maps 12. Citations 1. California Curriculum Content Standard, History/Social Science, 11th Grade: 11.10.2 — Examine and analyze the key events, policies, and court cases in the evolution of civil rights, including Dred Scott v. Sandford, Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, and California Proposition 209. 11.10.4 — Examine the roles of civil rights advocates (e.g., A. Philip Randolph, Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Thurgood Marshall, James Farmer, Rosa Parks), including the significance of Martin Luther King, Jr. ‘s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” and “I Have a Dream” speech. 3 2. CENTRAL HISTORICAL QUESTION: Considering issues of race, housing, and the struggle for civil rights in post-World War II Los Angeles, how valid is the statement from some in the African American community looking back: “We got what we wanted, but we lost what we had”? Before WWII: • 1940s and 1950s - Segregation in housing. • Shelley v. Kraemer, 1948 and Barrows vs. Jackson, 1953 – U.S. Supreme Court decisions abolish. • Map activities - Internet-based research on the geographic and demographic movements of the African American community in Los Angeles. • Locating homes of prominent African Americans. • Shift of African Americans away from central city to middle-class communities outside of the ghetto, resulting in a poorer and more segregated central city.