APHRODITE and ARES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

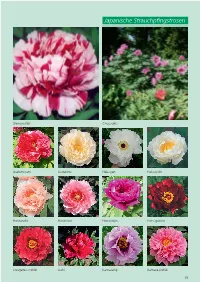

Japanische Strauchpfingstrosen

Japanische Strauchpfingstrosen Shimanishiki Chojuraku Asahiminato Godaishu Hakugan Hakuojishi Hanaasobi Hanakisoi Hanadaijin Hatsugarasu Jitsugetsu-nishiki Jushi Kamatafuji Kamata-nishiki 15 Kao Kokamon Kokuryu-nishiki Luo Yang Hong Meikoho Naniwa-nishiki Renkaku Rimpo Seidai Shim-daijin Shimano-fuji Shinfuso Shin-jitsugetsu Shinshifukujin Shiunden Taiyo Tamafuyo 16 Tamasudare Teni Yachiyotsubaki Yaezakura Yagumo Yatsukajishi Yoshinogawa High Noon Kinkaku Kinko Hakugan Kao 17 Europäische Strauchpfingstrosen Blanche de His Duchesse de Morny Isabelle Riviere Reine Elisabeth Chateau de Courson Jeanne d‘Arc Jacqueline Farvacques Zenobia 18 Rockii-Hybriden Souvenir de Lothar Parlasca Jin Jao Lou Ambrose Congrève Dojean E Lou Si Ezra Pound Fen He Guang Mang Si She Hai Tian E Hei Feng Die Hong Lian Hui He Ice Storm Katrin 19 Lan He Lydia Foote Rockii Ebert Schiewe Shu Sheng Peng Mo Souvenir de Ingo Schiewe Xue Hai Bing Xin Ye Guang Bei Zie Di Jin Feng deutscher Rockii-Sämling Lutea-, Delavayi- und Potaninii-Hybriden Anna Marie Terpsichore 20 Age of Gold Alhambra Alice in Wonderland Amber Moon Angelet Antigone Aphrodite Apricot Arcadia Argonaut Argosy Ariadne Artemis Banquet Black Douglas Black Panther Black Pirate Boreas Brocade Canary 21 Center Stage Chinese Dragon Chromatella Corsair Daedalus Damask Dare Devil Demetra Eldorado Flambeau Gauguin Gold Sovereign Golden Bowl Golden Era Golden Experience Golden Finch Golden Hind Golden Isle Golden Mandarin Golden Vanity 22 Happy Days Harvest Hélène Martin Helios Hephestos Hesperus Icarus Infanta Iphigenia Kronos L‘Espérance L‘Aurore La Lorraine Leda Madame Louis Henry Marchioness Marie Laurencin Mine d‘Or Mystery Narcissus 23 Nike Orion P. delavayi rot P. delavayi orange P. ludlowii P. lutea P. -

St. Michael and Attis

St. Michael and Attis Cyril MANGO Δελτίον XAE 12 (1984), Περίοδος Δ'. Στην εκατονταετηρίδα της Χριστιανικής Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας (1884-1984)• Σελ. 39-62 ΑΘΗΝΑ 1986 ST. MICHAEL AND ATTIS Twenty years ago, when I was working on the apse mosaics of St. Sophia at Constantinople, I had ample opportunity to contemplate what is surely one of the most beautiful works of Byzantine art, I mean the image of the archangel Gabriel, who stands next to the enthroned Theotokos (Fig. 1). Gabriel is dressed in court costume; indeed, one can affirm that his costume is imperial, since he is wearing red buskins and holding a globe, the symbol of universal dominion. Yet neither the Bible nor orthodox doctrine as defined by the Fathers provides any justification for portraying an archangel in this guise; no matter how great was his dignity in heaven, he remained a minister and a messenger1. Only God could be described as the equivalent of the emperor. How was it then that Byzantine art, which showed extreme reluctance to give to Christ, the pambasileus, any visible attributes of royalty other than the throne, granted these very attributes to archangels, who had no claim to them? An enquiry I undertook at the time (and left unpublished) suggested the following conclusions: 1. The Byzantines themselves, I mean the medieval Byzantines, could offer no reasonable explanation of the iconography of archangels and seemed to be unaware of its meaning. On the subject of the globe I found only two texts. One was an unedited opuscule by Michael Psellos, who, quite absurdly, considered it to denote the angels' rapidity of movement; "for", he says, "the sphere is such an object that, touching as it does only a tiny portion of the ground, is able in less than an instant to travel in any direction"2. -

Tammuz Pan and Christ Otes on a Typical Case of Myth-Transference

TA MMU! PA N A N D C H R IST O TE S O N A T! PIC AL C AS E O F M! TH - TR ANS FE R E NC E AND DE VE L O PME NT B! WILFR E D H SC HO FF . TO G E THE R WIT H A BR IE F IL L USTR ATE D A R TIC L E O N “ PA N T H E R U STIC ” B! PAU L C AR US “ " ' u n wr a p n on m s on u cou n r , s n p r n u n n , 191 2 CHIC AGO THE O PE N CO URT PUBLISHING CO MPAN! 19 12 THE FA N F PRAXIT L U O E ES. a n t Fr ticpiccc o The O pen C ourt. TH E O PE N C O U RT A MO N TH L! MA GA! IN E Devoted to th e Sci en ce of Religion. th e Relig ion of Science. and t he Exten si on of th e Religi on Periiu nen t Idea . M R 1 12 . V XX . P 6 6 O L. VI o S T B ( N . E E E , 9 NO 7 Cepyricht by The O pen Court Publishing Gumm y, TA MM ! A A D HRI T U , P N N C S . NO TES O N A T! PIC AL C ASE O F M! TH-TRANSFERENC E AND L DEVE O PMENT. W D H H FF. -

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction

Aspects of the Demeter/Persephone myth in modern fiction Janet Catherine Mary Kay Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (Ancient Cultures) at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr Sjarlene Thom December 2006 I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature: ………………………… Date: ……………… 2 THE DEMETER/PERSEPHONE MYTH IN MODERN FICTION TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction: The Demeter/Persephone Myth in Modern Fiction 4 1.1 Theories for Interpreting the Myth 7 2. The Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.1 Synopsis of the Demeter/Persephone Myth 13 2.2 Commentary on the Demeter/Persephone Myth 16 2.3 Interpretations of the Demeter/Persephone Myth, Based on Various 27 Theories 3. A Fantasy Novel for Teenagers: Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood 38 by Meredith Ann Pierce 3.1 Brown Hannah – Winter 40 3.2 Green Hannah – Spring 54 3.3 Golden Hannah – Summer 60 3.4 Russet Hannah – Autumn 67 4. Two Modern Novels for Adults 72 4.1 The novel: Chocolat by Joanne Harris 73 4.2 The novel: House of Women by Lynn Freed 90 5. Conclusion 108 5.1 Comparative Analysis of Identified Motifs in the Myth 110 References 145 3 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The question that this thesis aims to examine is how the motifs of the myth of Demeter and Persephone have been perpetuated in three modern works of fiction, which are Treasure at the Heart of the Tanglewood by Meredith Ann Pierce, Chocolat by Joanne Harris and House of Women by Lynn Freed. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Attis, a Case Study

Conceptual machinery of the mythopoetic mind: Attis, a case study S´andorDar´anyi1 and Peter Wittek1;2 1 University of Bor˚as,Sweden 2 ICFO-The Institute of Photonic Sciences Abstract. In search for the right interpretation regarding a body of re- lated content, we screened a small corpus of myths about Attis, a minor deity from the Hellenistic period in Asia Minor to identify the noncom- mutativity of key concepts used in storytelling. Looking at the protag- onist's typical features, our experiment showed incompatibility with re- gard to his gender and downfall. A crosscheck for entanglement found no violation of a Bell inequality, its best approximation being on the border of the local polytope. 1 Introduction With Ref. [1] now presenting \quantum information science" to the public, re- porting on work in progress, below we look at two of the key phenomena of quantum mechanics (QM), noncommutativity and entanglement. To contrast Refs. [2{4], Refs. [5] or [6]'s methodological claims, we are inter- ested to find out if conceptual entanglement may be shown outside of a cogni- tively typical questionnaire or polling scenario, in our case, in classical narratives populating mythologies, with text variants considered as repeated measurements of the same experiment. One of the aforementioned pioneering efforts, Ref. [7] employed four concepts (horse, bear, tiger, cat) in the Animal category vs. four vocal reactions (growl, whinny, snort, meow) from the Act category to create ex- amples of The Animal Acts predicate and have users rank the typicality of the resulting combinations. On the other hand, in the literary analysis we depart from, below we describe our subject matter, The Protagonist Acts, by means of a pair of logical oppositions, one pertaining to the gender of the hero, the other to his downfall. -

Heidi Savage April 2017 Kypris, Aphrodite, Venus, and Puzzles About Belief My Aim in This Paper Is to Show That the Existence Of

Heidi Savage April 2017 Kypris, Aphrodite, Venus, and Puzzles About Belief My aim in this paper is to show that the existence of empty names raise problems for the Millian that go beyond the traditional problems of accounting for their meanings. Specifically, they have implications for Millian strategies for dealing with puzzles about belief. The standard move of positing a referent for a mythical name to avoid the problem of meaning, because of its distinctly Millian motivation, implies that solving puzzles about belief, when they involve empty names, do in fact require reliance on Millianism after all. 1. Introduction The classic puzzle about belief involves a speaker who lacks knowledge of certain linguistic facts, specifically, knowledge that two distinct names refer to one and the same object -- that they are co-referential. Because of this lack of knowledge, it becomes possible for a speaker to maintain conflicting beliefs about the object in question. This becomes puzzling when we consider the idea that co-referential terms ought to be intersubstitutable in all contexts without any change in meaning. But belief puzzles show not only that this is false, but that it can actually lead to attributing contradictory beliefs to a speaker. The question, then, is what underlying assumption is causing the puzzle? The most frequent response has been to simply conclude that co-referentiality does not make for synonymy. And this conclusion, of course, rules out the Millian view of names – that the meaning of a name is its referent. Kripke, however, argues that belief puzzles are independent any particularly Millian assumptions. -

STONEFLY NAMES from CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Perla Jahr/Year: 1996 Band/Volume: 14 Autor(en)/Author(s): Ricker William E. Artikel/Article: Stonefly names from classical times 37-43 STONEFLY NAMES FROM CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker Recently I amused myself by checking the stonefly names that seem to be based on the names of real or mythological persons or localities of ancient Greece and Rome. I had copies of Bulfinch’s "Age of Fable," Graves; "Greek Myths," and an "Atlas of the Ancient World," all of which have excellent indexes; also Brown’s "Composition of Scientific Words," And I have had assistance from several colleagues. It turned out that among the stonefly names in lilies’ 1966 Katalog there are not very many that appear to be classical, although I may have failed to recognize a few. There were only 25 in all, and to get even that many I had to fudge a bit. Eleven of the names had been proposed by Edward Newman, an English student of neuropteroids who published around 1840. What follows is a list of these names and associated events or legends, giving them an entomological slant whenever possible. Greek names are given in the latinized form used by Graves, for example Lycus rather than Lykos. I have not listed descriptive words like Phasganophora (sword-bearer) unless they are also proper names. Also omitted are geographical names, no matter how ancient, if they are easily recognizable today — for example caucasica or helenica. alexanderi Hanson 1941, Leuctra. -

Aurora (Mythology)

Aurora (mythology) 2 Usage in literature and music Aurora, by Guercino, 1621-23: the ceiling fresco in the Casino Ludovisi, Rome, is a classic example of Baroque illusionistic painting Aurora (Latin: [awˈroːra]) is the Latin word for dawn, and the goddess of dawn in Roman mythology and Latin poetry. Like Greek Eos and Rigvedic Ushas (and possi- bly Germanic Ostara), Aurora continues the name of an earlier Indo-European dawn goddess, Hausos. Aurora Taking Leave of Tithonus 1 Roman mythology 1704, by Francesco Solimena From Homer's Iliad: In Roman mythology, Aurora, goddess of the dawn, re- news herself every morning and flies across the sky, an- Now when Dawn in robe of saffron was has- nouncing the arrival of the sun. Her parentage was flex- tening from the streams of Okeanos, to bring ible: for Ovid, she could equally be Pallantis, signifying light to mortals and immortals, Thetis reached the daughter of Pallas,[1] or the daughter of Hyperion.[2] the ships with the armor that the god had given She has two siblings, a brother (Sol, the sun) and a sis- her. (19.1) ter (Luna, the moon). Rarely Roman writers[3] imitated Hesiod and later Greek poets and named Aurora as the mother of the Anemoi (the Winds), who were the off- But soon as early Dawn appeared, the rosy- spring of Astraeus, the father of the stars. fingered, then gathered the folk about the pyre of glorious Hector. (24.776) Aurora appears most often in sexual poetry with one of her mortal lovers. A myth taken from the Greek by Ro- man poets tells that one of her lovers was the prince of From Virgil's Aeneid: Troy, Tithonus. -

Greek Mythology

Greek Mythology The Creation Myth “First Chaos came into being, next wide bosomed Gaea(Earth), Tartarus and Eros (Love). From Chaos came forth Erebus and black Night. Of Night were born Aether and Day (whom she brought forth after intercourse with Erebus), and Doom, Fate, Death, sleep, Dreams; also, though she lay with none, the Hesperides and Blame and Woe and the Fates, and Nemesis to afflict mortal men, and Deceit, Friendship, Age and Strife, which also had gloomy offspring.”[11] “And Earth first bore starry Heaven (Uranus), equal to herself to cover her on every side and to be an ever-sure abiding place for the blessed gods. And earth brought forth, without intercourse of love, the Hills, haunts of the Nymphs and the fruitless sea with his raging swell.”[11] Heaven “gazing down fondly at her (Earth) from the mountains he showered fertile rain upon her secret clefts, and she bore grass flowers, and trees, with the beasts and birds proper to each. This same rain made the rivers flow and filled the hollow places with the water, so that lakes and seas came into being.”[12] The Titans and the Giants “Her (Earth) first children (with heaven) of Semi-human form were the hundred-handed giants Briareus, Gyges, and Cottus. Next appeared the three wild, one-eyed Cyclopes, builders of gigantic walls and master-smiths…..Their names were Brontes, Steropes, and Arges.”[12] Next came the “Titans: Oceanus, Hypenon, Iapetus, Themis, Memory (Mnemosyne), Phoebe also Tethys, and Cronus the wily—youngest and most terrible of her children.”[11] “Cronus hated his lusty sire Heaven (Uranus). -

Robert Graves the White Goddess

ROBERT GRAVES THE WHITE GODDESS IN DEDICATION All saints revile her, and all sober men Ruled by the God Apollo's golden mean— In scorn of which I sailed to find her In distant regions likeliest to hold her Whom I desired above all things to know, Sister of the mirage and echo. It was a virtue not to stay, To go my headstrong and heroic way Seeking her out at the volcano's head, Among pack ice, or where the track had faded Beyond the cavern of the seven sleepers: Whose broad high brow was white as any leper's, Whose eyes were blue, with rowan-berry lips, With hair curled honey-coloured to white hips. Green sap of Spring in the young wood a-stir Will celebrate the Mountain Mother, And every song-bird shout awhile for her; But I am gifted, even in November Rawest of seasons, with so huge a sense Of her nakedly worn magnificence I forget cruelty and past betrayal, Careless of where the next bright bolt may fall. FOREWORD am grateful to Philip and Sally Graves, Christopher Hawkes, John Knittel, Valentin Iremonger, Max Mallowan, E. M. Parr, Joshua IPodro, Lynette Roberts, Martin Seymour-Smith, John Heath-Stubbs and numerous correspondents, who have supplied me with source- material for this book: and to Kenneth Gay who has helped me to arrange it. Yet since the first edition appeared in 1946, no expert in ancient Irish or Welsh has offered me the least help in refining my argument, or pointed out any of the errors which are bound to have crept into the text, or even acknowledged my letters. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.