Unlocking Exmoor's Woodland Potential Final Report August 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019

Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019 First published July 2021 Natural England Research Report NERR099 www.gov.uk/natural-england Nettlecombe NVC Final Report Natural England Research Report NERR099 Natural England Research Report NERR099 Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019 A.McLay July 2021 This report is published by Natural England under the Open Government Licence - OGLv3.0 for public sector information. You are encouraged to use, and reuse, information subject to certain conditions. For details of the licence visit Copyright. Natural England photographs are only available for non-commercial purposes. If any other information such as maps or data cannot be used commercially this will be made clear within the report. ISBN: 978-1-78354-770-8 © Natural England 2021 Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019 Natural England Research Report NERR099 Project details This report should be cited as: McLay, A. 2021. Nettlecombe Court Slope and Old Weather Station Field: National Vegetation Classification 2019 Natural England Research Report NERR099. Natural England. Natural England Project manager Mike Pearce Author A.McLay Keywords Nettlecombe Park, grassland survey, grassland fungi, SSSI Further information This report can be downloaded from the Natural England Access to Evidence Catalogue: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/ . For information on Natural England publications -

January-February 2021

Page 1 Issue No. 127 Village News January - February 2021 Monkton Heathfield, West Monkton and Bathpool Getting Up-Close and Personal with a Wooly Mamoth See Page 8 Contents: Useful Numbers/Regular Bookings - Page 2 Somerset Birds - Page 3 Broomsquires - Page 4 & 5 South Quantock Benefice - Page 6 Bishop Peter/Bathpool Chapel/100 Club - Page 7 School News - Page 8 Oak Partnership/Gardening Corner - Page 9 Find out more about Carrion Crows Parish Council - Pages 10 & 11 See Page 3 WI Walks - Page 12 Sports Pitches - Page 13 Happy New Year Memories of Hestercombe - Page 14 from Hestercombe Cont/Village Hall - Page 15 all of us at the Village News WM&CF Film Club/Blood Donations/Debt Help/Walking Football - Page 16 Taunton Scrubbers/And Finally - Page 24 Publication in the Village News does not imply an endorsement. The Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or omissions. The information contained within this publication is published in good faith. Volunteers deliver this publication to homes in West Monkton, Monkton Heathfield, Bathpool, Gotton and Goosenford. Copy deadline for March - April 2021 is 1st February 2021 Page 2 Useful Names and Telephone Numbers Regular Events at West Monkton Village Hall Monkton Heathfield, TA2 8NE Rector: Rev. Mary Styles - 01823 451189 The Vicarage, Kingston St Mary, TA2 8HW Slimming World Associate Vicar half-time: Rev Jim Cox - 01823 333377 Mondays 09:00 - 11:00 Churchwarden: Hazel Adams - 01823 443027 Phoenix Camera Club P.C.C Secretary: Samm Barge - 07976415337 Mondays 19:00 - 22:00 P.C.C -

Somerset Minerals and Waste Development Framework Sustainability Appraisal & Strategic Environmental Assessment Scoping Report February 2011

Somerset Minerals Plan Preferred Options Paper Sustainability Appraisal Report Prepared for Somerset County Council by LUC December 2012 Project Title: Somerset Minerals Plan Preferred Options Paper Sustainability Appraisal Report Client: Somerset County Council Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by Principal 1 05.11.12 First Draft Report Ifan Gwilym Catrin Owen Jeremy Owen Catrin Owen 2 16.11.12 Final Report Ifan Gwilym Catrin Owen Jeremy Owen Catrin Owen Jeremy Owen 3 14.12.12 Final Report – signed-off Ifan Gwilym Catrin Owen Jeremy Owen version Catrin Owen Jeremy Owen J:\CURRENT PROJECTS\4600s\4629 Somerset Minerals\4629.01\B Project Working\2012 Project restart\SA Report\4629_SomersetMineralsSA_20121116_v3_0.docx Somerset Minerals Plan Preferred Options Paper Sustainability Appraisal Report Prepared for Somerset County Council by LUC December 2012 Planning & EIA LUC BRISTOL Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 14 Great George Street London Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning Bristol BS1 5RH Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management Tel:0117 929 1997 Edinburgh 43 Chalton Street Ecology Fax:0117 929 1998 London NW1 1JD LUC uses 100% recycled paper Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 Contents 1 Non-Technical Summary 1 2 Introduction 30 3 Somerset Minerals Plan Preferred Options Paper 34 4 Appraisal Methodology 41 5 Environmental, social and economic policy objectives of relevant plans and programmes 45 6 Sustainability Context for -

Published by ENPA November 2009 1 EXMOOR NATIONAL PARK

EXMOOR NATIONAL PARK EMPLOYMENT LAND REVIEW Published by ENPA November 2009 1 Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd 1st Floor, Westville House Fitzalan Court Cardiff CF24 0EL Offices also in T 029 2043 5880 London F 029 2049 4081 Manchester Newcastle upon Tyne [email protected] www.nlpplanning.com Contents2 Executive Summary 5 1.0 INTRODUCTION 11 Scope of the Study 11 The Implications of Exmoor’s Status as a National Park 13 Methodology 15 Report Structure 18 2.0 Local Context 19 Geographical Context 19 Population 21 Economic Activity 22 Distribution of Employees by Sector 25 Qualifications 28 Deprivation 29 Commuting Patterns 32 Businesses 36 Conclusion 36 3.0 Policy Context 37 Planning Policy Context 37 Economic Policy Context 42 Conclusion 48 4.0 The Current Stock of Employment Space 50 Existing Stock of Employment Floorspace 50 Existing Employment Land Provision 55 Conclusion 61 5.0 Consultation 63 Agent Interviews 63 Stakeholder Consultation 65 Business Consultation 68 Previous Consultation Exercises 73 Conclusion 80 6.0 Qualitative Assessment of Existing Employment Sites 81 Conclusion 90 7.0 The Future Economy of Exmoor National Park 92 Establishing an Economic Strategy 92 Influences upon the Economy 93 Key Sectors 95 1 30562/517407v2 Conclusion 97 8.0 Future Need for Employment Space 99 Employment Growth 99 Employment Based Space Requirements 105 Planning Requirement for Employment Land 112 9.0 The Role of Non-B Class Sectors in the Local Economy 114 Introduction 114 Agriculture 114 Public Sector Services 119 Retail 122 10.0 -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk. -

Minehead to Combe Martin | Habitats Regulation Assessment Contents: Contents:

www.gov.uk/englandcoastpath Assessment of England Coast Path proposals between Minehead and Combe Martin on Exmoor Heaths and Exmoor and Quantock Oakwoods Special Areas of Conservation Version 2.0 Revised and updated: July 2020 1 England Coast Path | Minehead to Combe Martin | Habitats Regulation Assessment Contents: Contents: .......................................................................................................................... 2 Summary .......................................................................................................................... 3 PART A: Introduction and information about the England Coast Path ......................... 7 PART B: Information about the European Sites which could be affected .................. 10 PART C: Screening of the plan or project for appropriate assessment...................... 14 PART D: Appropriate Assessment and Conclusions on Site Integrity........................ 20 PART E: Permission decision with respect to European Sites ................................... 29 References to evidence................................................................................................. 30 Annex 1. Maps .............................................................................................................. 31 2 England Coast Path | Minehead to Combe Martin | Habitats Regulation Assessment Summary I) Introduction This is a record of the Habitats Regulations Assessment (‘HRA’) undertaken by Natural England, on behalf of the Secretary of State in accordance with -

British Lichen Society Bulletin No

1 BRITISH LICHEN SOCIETY OFFICERS AND CONTACTS 2010 PRESIDENT S.D. Ward, 14 Green Road, Ballyvaghan, Co. Clare, Ireland, email [email protected]. VICE-PRESIDENT B.P. Hilton, Beauregard, 5 Alscott Gardens, Alverdiscott, Barnstaple, Devon EX31 3QJ; e-mail [email protected] SECRETARY C. Ellis, Royal Botanic Garden, 20A Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR; email [email protected] TREASURER J.F. Skinner, 28 Parkanaur Avenue, Southend-on-Sea, Essex SS1 3HY, email [email protected] ASSISTANT TREASURER AND MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY H. Döring, Mycology Section, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] REGIONAL TREASURER (Americas) J.W. Hinds, 254 Forest Avenue, Orono, Maine 04473-3202, USA; email [email protected]. CHAIR OF THE DATA COMMITTEE D.J. Hill, Yew Tree Cottage, Yew Tree Lane, Compton Martin, Bristol BS40 6JS, email [email protected] MAPPING RECORDER AND ARCHIVIST M.R.D. Seaward, Department of Archaeological, Geographical & Environmental Sciences, University of Bradford, West Yorkshire BD7 1DP, email [email protected] DATA MANAGER J. Simkin, 41 North Road, Ponteland, Newcastle upon Tyne NE20 9UN, email [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR (LICHENOLOGIST) P.D. Crittenden, School of Life Science, The University, Nottingham NG7 2RD, email [email protected] BULLETIN EDITOR P.F. Cannon, CABI and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew; postal address Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, email [email protected] CHAIR OF CONSERVATION COMMITTEE & CONSERVATION OFFICER B.W. Edwards, DERC, Library Headquarters, Colliton Park, Dorchester, Dorset DT1 1XJ, email [email protected] CHAIR OF THE EDUCATION AND PROMOTION COMMITTEE: position currently vacant. -

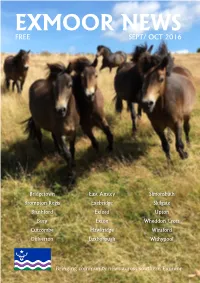

Sept Oct 2016

EXMOOR NEWS FREE SEPT/ OCT 2016 Bridgetown East Anstey Simonsbath Brompton Regis Exebridge Skilgate Brushford Exford Upton Bury Exton Wheddon Cross Cutcombe Hawkridge Winsford Dulverton Luxborough Withypool Bringing community news across southern Exmoor Delicious Local Food and Drink. Confectionery, Gifts and Cards. Wines, Spirits, Ales and Ciders - Exmoor Gin. Celebrating 75 years And Much More! Traditional Shop Open 7 days a week Fore Street, Dulverton T: 01398 323465 Café & Deli www.tantivyexmoor.co.uk EXMOOR NEWS DULVERTON & SOUTHERN EXMOOR The country year is jam packed with fairs, fetes, flower shows, live music, steam rallies, markets and a myriad other quirky events - none of which would exist without the goodwill of volunteers. Exmoor News would like to celebrate these ‘Unsung Heroes’ who elevate our lives from the ordinary, by publishing some of their background stories. We hope that by highlighting what they do, we can inspire the next generation of volunteers, so to that end, if you have a story to tell or would like to write about someone you know, email us! Please continue to let advertisers know if you found them in our magazine - as it means we can keep providing our magazine free to you. If you have any other stories you would like to share, please email us. Best wishes Ceri Keene and Claire Savill Contact Details E: [email protected] T: 07497 914441 W: www.exmoornews.co.uk Post: The Old Stores, Brushford, Dulverton, Somerset, TA22 9AH The deadline for the November/December issue of the Exmoor News is Thursday 6th October 2016 Printed by Brightsea, Exeter Cover photo: Holtball Herd 11 Exmoor ponies © Dawn Westcott, author of Wild Pony Whispering and Wild Stallion Whispering who runs the Moorland Exmoor Foal Project. -

Somersetshire

324: MtSTEBTON. [ KELLY'S • SOMERSETSHIRE. Somerset Trading Company Limited, Symes Ell, grocer & butcher Yeaxlee Nelson, baker coal, timber, slate & general mer- Vardy George, grocer, Post office Young John, Sw-an inn chants, Railway station MONKSILVER is a village and parish, on the road Notley esq. of Combe Sydenham, Stogumber, is lord of the from Minehead to Taunton, 3 miles west from Stogumber manor and principal landowner. The soil is a sandy loam; station and 4 south-south-west from Williton station on the subsoil marl, and produces excellent crops of wheat, barle~-,. West Somerset hranch of the Great Western railway,7 north oats, mangolds, potatoes and turnips. The acreage of the from Wiveliscombe and 13 north-west from Taunton, in the parish is x,oo6; rateable value, £1,242; the population in Western division of the county, hundred of Williton and 1891 was tBB civil and 191 ecclesiastical. Freemanors, Williton petty sessional division, union and On March 25, x884, by Local GoveTnment Board Orde~ county court district, rural deanery of Wiveliscombe, arch 14,606, a detached part of this parish, known as Doniford.,. deaconry of Taunton and diocese of Bath and Wells The was amalgamated with Old Cleeve for civil purposes. church of All Saints is a small edifice in the Perpendicular Sexton, William Calloway. style, consisting of chancel, nave of four bays, south aisle, south porch and an embattled western tower containing 5 PosT OFFICE.-John Hole, sub-postmaster. Letters arrive- bells and a clock, given by Miss Gatchell, in memory of from Taunton at 7.20 a. m. -

Gotelee Orchard-Lisle

MONKSILVER PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF QUARTERLY MEETING HELD ON 26th FEBRUARY 2016 AT EMN COMMUNITY HALL Present: Cllrs. Mervyn Orchard-Lisle, (Chairman), Andrew Howe (Vice-Chairman), Kate Adams, Dan Cotterill, John Notley, David Vere Hodge, Ross Urquhart (Clerk); County Cllr. Christine Lawrence, Debbie Dennis (Village Agent) Apologies: Sue Westbury 1. Minutes of last meeting were agreed without amendment. 2. There were no declarations of interest. 3. Matters arising: 3.1 The appeal relating to the solar panels at Aller Farm has been dismissed. 3.2 It was agreed to add the defibrillator to the Parish Council insurance at a premium of £25 per annum. Proposed by Andrew and seconded by David. 3.3 Publicity for the defibrillator appeared in WS Free Press on 26th Feb, thanks to Sue. Ross has distributed information to all the villagers on the recommended procedure if it needs to be used. 3.4 Mervyn requested his mobile no. be added to the contacts list on website. 3.5 No further Code of Conduct training courses are planned by WSC in the near future. 3.6 Kate reported that the coffee mornings at the pub were no longer taking place as the result of minimal attendance. 3.7 The next Deer Management Group (DMG) meeting is in April, so there is nothing to report. 4. Loneliness and Well-Being. Various options for using the SCC £500 grant were discussed and discounted. These options included funding for a stroke rehabilitation club, a subsidy for the Valley Luncheon Club and an additional handrail on the slope down to the EMN Hall. -

PART 4: Landscape Character Assessment of Exmoor

Exmoor Landscape Character Assessment 2017 PART 4: Landscape Character Assessment of Exmoor 59 Consultation Draft, May 2017 Fiona Fyfe Associates Exmoor Landscape Character Assessment 2017 PART 4: LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT OF EXMOOR Landscape Character Types and Areas Landscape Character Assessment 4.1 Exmoor’s Landscape Character Types and Areas Landscape Character Type (LCT) Landscape Character Area (LCA) A: High Coastal Heaths A1: Holdstone Down and Trentishoe A2: Valley of Rocks A3: The Foreland A4: North Hill B: High Wooded Coast Combes and Cleaves B1: Heddon’s Mouth B2: Woody Bay B3: Lyn B4: Culbone - Horner B5: Bossington B6: Culver Cliff C: Low Farmed Coast and Marsh C1: Porlock D: Open Moorland D1: Northern D2: Southern D3: Winsford Hill D4: Haddon Hill E: Farmed and Settled Vale E1 Porlock – Dunster - Minehead F: Enclosed Farmed Hills with Commons F1: Northern F2: Southern F3: Eastern G: Incised Wooded Valleys G1: Bray G2: Mole G3: Barle G4: Exe G5: Haddeo G6: Avill H: Plantation (with Heathland) Hills H1: Croydon and Grabbist I: Wooded and Farmed Hills with Combes I1: The Brendons 60 Fiona Fyfe Associates Consultation Draft, May 2017 Exmoor Landscape Character Assessment 2017 PART 4: LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT OF EXMOOR Landscape Character Types and Areas Map 5: Landscape Character Types and Areas within Exmoor National Park 61 Consultation Draft, May 2017 Fiona Fyfe Associates Exmoor Landscape Character Assessment 2017 PART 4: LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT OF EXMOOR Landscape Character Types and Areas Landscape Character Types Landscape Character Types are distinct types of landscape that are relatively homogenous in character. They are generic in nature in that they may occur in different areas...but wherever they occur they share broadly similar combinations of geology, topography, drainage patterns, vegetation, historical land use, and settlement pattern1. -

Somerset Minerals and Waste Development Framework Sustainability Appraisal & Strategic Environmental Assessment Scoping Report February 2011

Somerset Minerals Plan Sustainability Appraisal Report Prepared for Somerset County Council by LUC December 2013 Project Title: Somerset Minerals Plan Sustainability Appraisal Report Client: Somerset County Council Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by Principal 0.1 18.09.13 First Draft Report Ifan Gwilym Catrin Owen 1.0 30.09.13 Final Draft Report Ifan Gwilym Catrin Owen Catrin Owen 1.2 01.10.13 Final Draft Report – Chapter Catrin Owen Catrin Owen 9 and NTS complete 2.0 03.10.13 Final Report for Members Catrin Owen Catrin Owen comments 2.5 04.11.13 Revised to reflect Plan Ifan Gwilym, Catrin Owen Jeremy Owen amendments Catrin Owen 2.7 12.12.13 Revised to reflect Plan Catrin Owen Catrin Owen Jeremy Owen amendments 3.0 13.12.13 Final Ifan Gwilym Catrin Owen Jeremy Owen J:\CURRENT PROJECTS\4600s\4629 Somerset Minerals\4629.03 Final SA\B Project Working\4629_SomersetMineralsSA_FinalPlan_20131213_v3.0.docx Somerset Minerals Plan Sustainability Appraisal Report Prepared for Somerset County Council by LUC December 2013 Planning & EIA LUC BRISTOL Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 14 Great George Street London Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning Bristol BS1 5RH Glasgow Registered Office: Landscape Management Tel:0117 929 1997 Edinburgh 43 Chalton Street Ecology Fax:0117 929 1998 London NW1 1JD LUC uses 100% recycled paper Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 Contents 1 Non-Technical Summary 1 2 Introduction 26 3 Somerset Minerals Plan 31 4 Appraisal