Cage on the Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Next-Generation Sequencing Identi Es Seasonal And

Next-generation sequencing identies seasonal and geographical differences in the ruminal community composition of sika deer (Cervus nippon) in Japan Shinpei Kawarai ( [email protected] ) Azabu University Kensuke Taira Azabu University Ayako Shimono Toho University Tsuyoshi Takeshita Komoro City Oce Shiro Takeda Azabu University Wataru Mizunoya Azabu University Shigeharu Moriya RIKEN CSRS Masato Minami Azabu University Research Article Keywords: Posted Date: August 6th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-783658/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/27 Abstract To understand the nutritional conditions of culled wild sika deer (Cervus nippon) and their suitability as a pet food component, we compared the ruminal community compositions of deer living in different food habitats (Nagano winter, Nagano spring, and Hokkaido winter) using next-generation sequencing. Twenty-nine sika deer were sampled. Alpha and beta diversity metrics determined via 16S and 18S ssrRNA amplicon-seq analysis showed compositional differences. Prevotella, Entodinium, and Piromyces were the dominant genera of bacteria, fungi and protozoa, respectively. Moreover, 66 bacterial taxa, 44 eukaryotic taxa, and 46 chloroplastic taxa were shown to differ signicantly among the groups by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe). Total RNA-seq analysis showed 397 signicantly differentially expressed transcripts (q < 0.05), of which 258 were correlated with bacterial amplicon-seq results (Pearson correlation coecient > 0.7). The amplicon-seq results indicated that deciduous broadleaf trees and SAR were enriched in Nagano, whereas graminoids, Firmicutes and fungi were enriched in Hokkaido. The ruminal microbial community were corresponded with different food habits, related to the severe snow conditions in Hokkaido in winter and the richness of plants with leaves and acorns in Nagano winter and spring. -

Majestätisches Japan Motorrad Tour

Majestätisches Japan Land der aufgehenden Sonne 26. September — 11. Oktober, 2020 27. September — 12. Oktober, 2021 | 16. Oktober - 31. Oktober, 2021 Japan ist für viele Touristen eines der begehrtesten Reiseziele. Bei IMTBIKE haben wir eine Motorradroute ausgearbeitet mit wenig bekannten Straßen, raffiniertem japanischem Essen und einem reichhaltigen Angebot an Kultur und Geschichte. Auf dieser Tour genießt Du einen atemberaubenden Blick auf den Fuji, erlebst die üppigen Wälder der japanischen Alpen und entspannst in den berühmten natürlichen heißen Quellen, die wir auf unserem Weg vorfinden. Erlebe diesen Herbst auf eine ganz besondere andere Art und Weise und komme mit auf diese unglaublich schöne Motorradtour in Japan. Tourdaten Start /Ende: Tokyo Gesamtstrecke: 2.818 km / 1.740 Meilen Dauer: 16 Tage Fahrtage: 14 Tage Rasttage: 3: Kyoto, Hiroshima, Kusatsu Frühstück: 15 Frühstück inbegriffen Abendessen: 12 Abendessen inbegriffen Daily mileage: 160 - 220 km / 250-350 Meilen Hotelübernachtungen: 15 Nätche Fahrsaison: Herbst Higlights: Tokyo, Mount Fuji, Japanese Alps, Tsumago, Hotels: quality hotels and Japanese Ryokans. Ryokans are a Shikoku, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Eiheiji, Matsumoto, Kusatsu, type of traditional Japanese Inn that has existed since the 8th Nikko. century. The oldest hotel in the world is a Japanese Ryokan founded in 718 A.D. Prices Pilot*: 8050€ Passenger: 5800€ Single Room: 1200€ * im Doppelzimmer mit einer Honda NC750X/ SuzukiVStrom650 Bike Upgrade: BMW F750GS + 350€ BMW F850GS/R1200RS + 600€ BMW R1250GS + 895€ BMW R1250RT + 1215€ Tel (USA) (412) 468-2453 [email protected] Tel (España) (+34) 91 633 72 22 www.IMTBike.com Arrive to Japan and transfer to hotel. You will have some free time to relax or explore the Day 1: Odaiba bay area before the welcome briefing. -

Minakami Perfect Travel Guide &

N 4 One Drop Outdoor Guide Service N 9 S 5 English /Enjoy/ /Enjoy/ This popular tour uses inflatable rafts for canoeing around Lake Shima, which is one of the most transparent lakes in Nature the Kanto region. Snow Enjoy activities where you can experience the Enjoy natural snow close to the Tokyo MAP B-3 Wi-Fi richness of nature. Even first-timers can feel at ease metropolitan area. In addition to eight ski resorts, MINAKAMI 0278-72-8136 with rental equipment and experienced guides. 2230-1 Kamimoku, Minakami-machi there is also a variety of other activities. 8:00-18:00 Closed Open daily during the season Perfect Travel Guide & Map onedrop-outdoor.com/ N 1 Minakami Bungy N 5 Norn Minakami Ski Resort S 1 Tanigawadake Tenjindaira Ski Resort Wi-Fi Minakami Mountain Guide Association MAP A-2 This ski resort offers novice to expert Try bungee jumping from the MAP B-3 This ski resort offers gorgeous views of the Tanigawa 0278-72-3575 level trails and Snow Land, an area which Yubiso, Yubukiyama- 42-meter-high Suwakyo Ohashi Bridge mountain range. It is known for its long ski season, Hiking and trekking on Mount Tanigawa, Oze, 0278-62-0401 offers fun in the snow for everyone. Kokuyurin, Minakami-machi over the Tone River. 1744-1 Tsukiyono, lasting from early December to early May. Some areas December to March: and Mount Hotaka are offered here. One of the most Minakami-machi MAP A-3 Wi-Fi have snow as deep as four meters during the high 8:30-16:30 (final lift at popular activities is the eco-hiking tour from Mount 8:30-17:30 16:00), April to end of Tanigawa to Ichinokurasawa, one of Japan's three Closed Open daily during season, offering the ultimate powder skiing without any MAP B-1 0278-72-6688 479-139 Terama, Minakami-machi season: 8:00-17:00 (from greatest rocks, and hiking up Mount Tanigawa with its the season Mid-December to late March: 8:00-16:00 manmade snow. -

List of Volcanoes in Japan

Elevation Elevation Sl. No Name Prefecture Coordinates Last eruption Meter Feet 1 Mount Meakan Hokkaidō 1499 4916 43.38°N 144.02°E 2008 2 Mount Asahi (Daisetsuzan) Hokkaidō 2290 7513 43.661°N 142.858°E 1739 3 Lake Kuttara Hokkaidō 581 1906 42.489°N 141.163°E - 4 Lake Mashū Hokkaidō 855 2805 43.570°N 144.565°E - 5 Nigorigawa Hokkaidō 356 1168 42.12°N 140.45°E Pleistocene 6 Nipesotsu-Maruyama Volcanic Group Hokkaidō 2013 6604 43.453°N 143.036°E 1899 7 Niseko Hokkaidō 1154 3786 42.88°N 140.63°E 4050 BC 8 Oshima Hokkaidō 737 2418 41.50°N 139.37°E 1790 9 Mount Rausu Hokkaidō 1660 5446 44.073°N 145.126°E 1880 10 Mount Rishiri Hokkaidō 1721 5646 45.18°N 141.25°E 5830 BC 11 Shikaribetsu Volcanic Group Hokkaidō 1430 4692 43.312°N 143.096°E Holocene 12 Lake Shikotsu Hokkaidō 1320 4331 42.70°N 141.33°E holocene 13 Mount Shiretoko Hokkaidō 1254 4114 44°14′09″N 145°16′26″E 200000 BC 14 Mount Iō (Shiretoko) Hokkaidō 1563 5128 44.131°N 145.165°E 1936 15 Shiribetsu Hokkaidō 1107 3632 42.767°N 140.916°E Holocene 16 Shōwa-shinzan Hokkaidō 731 2400 42.5°N 140.8°E 1945 17 Mount Yōtei Hokkaidō 1898 6227 42.5°N 140.8°E 1050 BC 18 Abu (volcano) Honshū 571 - 34.50°N 131.60°E - 19 Mount Adatara Honshū 1718 5635 37.62°N 140.28°E 1990 20 Mount Akagi Honshū 1828 5997 36.53°N 139.18°E - 21 Akita-Komaga-Take Honshū 1637 5371 39.75°N 140.80°E 1971 22 Akita-Yake-Yama Honshū 1366 4482 39.97°N 140.77°E 1997 23 Mount Asama Honshū 2544 8340 36.24°N 138.31°E 2009 24 Mount Azuma Honshū 1705 5594 37.73°N 140.25°E 1977 25 Mount Bandai Honshū 1819 5968 37.60°N 140.08°E 1888 -

Mt.AKAGI Gunma Prefecture

Maebashi Access MAEBASHI TRAVEL GUIDE & MAP 黒檜山 Fukushima 赤城山第1赤城山第1スキー場 1828 Niigata 津久田駅 P.2・3 Mt. Kurobi 雪山登山 Take Prefecture Prefecture N P.5 Mt. Akagi No. 1 Ski Slope Snowy Mountain By Train 大沼 白樺牧場 Lake Onuma 1685 Climbing P.5 P.5 Shirakaba Farm P.2・4・5 駒ヶ岳 Asakusa Haneda Airport Narita Airport 前 橋 市 Mt. Komagatake Tochigi Station International Terminal Station 県立赤城公園ビジターセンター P.2・3 Free Maebashi City Prefecture 0 2km 1674 Terminal Station 城 P.2 The Akagi Visitors Center 地蔵岳 覚満淵 Mt. Jizodake Kakumanbuchi 赤城温泉ホテル Marsh P.3・5 Airport Terminal Shibukawa P.2 Akagi Onsen Hotel 1579 Keisei Skyliner ¥ 長七郎山 0 Limited Express 2 Station City 花の宿 湯之沢館 Mt. Choshichiro Gunma P.2 Hana no Yado Yunosawakan 1 Approx. 17 353Prefecture 御宿 総本家 25 min. P.2 Onyado Sohonke Keisei Skyliner 1332 滝沢館 Limited Express Saitama 鍋割山 赤城温泉 Takizawakan Shinagawa Nagano Mt. Nabewari Approx. Mito Station Prefecture Akagi Onsen P.2 Station Prefecture 富士見温泉 見晴らしの湯ふれあい館 45 min. 滝沢温泉 Fujimi Spa FUREAIKAN P.3 忠治温泉 Takizawa Onsen 道の駅 ふじみ Chuji Onsen 渋川駅 Road Station Fujimi 旅籠 忠治館 Kiryu JR Yamanote Line Keisei JR Joban Line Shibukawa 353 P.2 Approx. 10 min. Limited Express Station Hatago Chujikan Tobu Railway Ueno Station 赤城神社 City Express Approx. 17 前橋温泉 クア・イ・テルメ Akagi Shrine 赤城南面千本桜 70 min. 桑風庵本店 Approx. Walk Maebashi Spa Sofuan Honten Akagi Cherry 渋川伊香保渋川伊香保 KUR Y THERME P.3 110 min. 5 min. P.7 空っ風家 Blossoms P.4 関 関 Shibukawa Tokyo Station 越 越 P.7 K K Ikaho Karakkaze-ya 自 自 焼肉乃上州敷島店 a a 動 動 n P.6 車 Yakiniku no Joushu Shikishima Branch 赤城高原温泉 Joetsu/Nagano - Ueno Station E 道 353 敷島公園 ばら園 Akagi Kogen Onsen Shinkansen t 17 17 s ぐんまフラワーパーク u Shikishima Koen Rose Garden P.4 Approx. -

From Narita International Airport from Haneda Airport Transportation Guide There Sa Never-Ending List of Fun, Memorable E

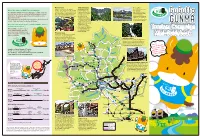

▼ Shima Onsen ▶ Mount Tanigawa ◀ Ozegahara Shima is celebrated as “the spring of Straddling the border Oze is one of the precious What is the GuGutto GUNMA Tourism Campaign? beauties.” This onsen town is full of simple, between Gunma and few remaining nostalgic charm. A famous event known as Niigata prefectures, this is The GuGutto GUNMA Tourism Campaign is a public-relations high-altitude wetlands. It's the “Chochin (Paper Lantern) Walk” is held counted as one of Japan’s a world rich in the variety program designed to spread the word about Gunma’s many here, in which people walk through the hundred most famous of rare living things, attractions, showing people all the excitement there is to town swinging paper lanterns in one hand. mountains. Mount including mountain plants discover in Gunma. Tanigawa’s rock walls, and insects. The grandeur The campaign is packed with new experiences and a variety of including Ichinokurasawa, and refreshing atmosphere are among the three most are a pleasure to witness. events. Come and taste the charms of Gunma! notable rock formations in Japan, and are considered Here’s what’s behind the theme, “GuGutto GUNMA ‒ Discover to be the Mecca of exciting new experiences.”: Japanese rock climbing. From trekking to full-blown We would like everyone to get mountain climbing, there excited with visiting attractive are many ways to enjoy spots and events in Gunma and Mount Tanigawa. ▼ Kusatsu Onsen have memorable experiences that Kusatsu is one of Japan’s most renowned get to your heart. onsen resorts, boasting the highest amount of natural hot water discharge of Oze any onsen resorts in the country. -

List of Volcanoes in Japan - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 8

List of volcanoes in Japan - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 8 List of volcanoes in Japan From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia See also: List of volcanoes This is a list of active and extinct volcanoes in Japan. Contents ■ 1 Hokkaidō ■ 2 Honshū ■ 3 Izu Islands ■ 4 Kyūshū ■ 5 Ryukyu Islands ■ 6 Other ■ 7 References ■ 7.1 Notes ■ 7.2 Sources http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_volcanoes_in_Japan 4/7/2011 List of volcanoes in Japan - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 2 of 8 Hokkaidō Elevation Elevation Last eruption Name Coordinates (m) (ft) Mount Meakan 1499 4916 43.38°N 144.02°E 2006 Mount Asahi (Daisetsuzan) 2290 7513 43.661°N 142.858°E 1739 Mount E 618 2028 41.802°N 141.170°E 1874 Hokkaidō Komagatake 1131 3711 42.061°N 140.681°E 2000 Kutcharo 1000 3278 43.55°N 144.43°E - Lake Kuttara 581 1906 42.489°N 141.163°E - Lake Mashū 855 2805 43.570°N 144.565°E - Nigorigawa 356 1168 42.12°N 140.45°E Pleistocene Nipesotsu-Maruyama Volcanic 2013 6604 43.453°N 143.036°E 1899 Group Niseko 1154 3786 42.88°N 140.63°E 4050 BC Oshima 737 2418 41.50°N 139.37°E 1790 Mount Rausu 1660 5446 44.073°N 145.126°E 1880 Mount Rishiri 1721 5646 45.18°N 141.25°E 5830 BC Shikaribetsu Volcanic Group 1430 4692 43.312°N 143.096°E Holocene Lake Shikotsu 1320 4331 42.70°N 141.33°E 1981 44°14′09″N Mount Shiretoko 1254 4114 145°16′26″E Mount Iō (Shiretoko) 1563 5128 44.131°N 145.165°E 1936 Shiribetsu 1107 3632 42.767°N 140.916°E Holocene Showashinzan 731 2400 42.5°N 140.8°E 1945 Mount Tokachi 2077 6814 43.416°N 142.690°E 1989 42°41′24″N Mount Tarumae 1041 -

Socioeconomic Significance of Landslides

kChapter 2 ROBERT L. SCHUSTER SOCIOECONOMIC SIGNIFICANCE OF LANDSLIDES 1. INTRODUCTION wildlife), landslides destroy or damage residential and industrial developments as well as agricultural andslides have been recorded for several and forest lands and negatively affect water qual- L centuries in Asia and Europe. The oldest ity in rivers and streams. landslides on record occurred in Honan Province Landslides are responsible for considerably in central China in 1767 B.C., when earthquake- greater socioeconomic losses than is generally rec- triggered landslides dammed the Yi and Lo rivers ognized; they represent a significant element of (Xue-Cai and An-ning 1986). many major multiple-hazard disasters. Much land- The following note by Marinatos may well refer slide damage is not documented because it is con- to a catastrophic landslide resulting in serious so- sidered to be a result of the triggering process (i.e., cial and economic losses: part of a multiple hazard) and thus is included by the news media in reports of earthquakes, floods, In the year 3 73/2 B.C., during a disastrous win- volcanic eruptions, or typhoons, even though the ter night, a strange thing happened in central cost of damage from landslides may exceed all Greece. Helicé, a great and prosperous town other costs from the overall multiple-hazard disas- on the north coast of the Peloponnesus, was ter. For example, it was not generally recognized engulfed by the waves after being leveled by a by the media that most of the losses due to the great earthquake. Not a single soul survived. 1964 Alaska earthquake resulted from ground fail- (Marinatos 1960) ure rather than from shaking of structures. -

GUNMA PREFECTURE Latest Update: August 2013

www.EUbusinessinJapan.eu GUNMA PREFECTURE Latest update: August 2013 Prefecture’s Flag Main City: Maebashi Population: 1,985,000 people ranking 19/47 prefecture (2013) [1] Area: 6,363 km2 [2] Geographical / Landscape description Gunma Prefecture is located in the middle of Honshu, around 100km from the capital, Tokyo. One of only eight landlocked prefectures in Japan, Gunma is the north western-most prefecture of the Kanto plain. Except for the central and southeast areas, where most of the population is concentrated, it is mostly mountainous. [2] Climate Because of its inland location there is a significant temperature difference between summer and winter. Thanks to the so called “karakaze” a strong, dry wind which occurs in the winter, and to the protection offered by the Echigo mountains, the prefecture records a relatively low level of winter precipitation. [2] Time zone: GMT +7 in summer (+8 in winter) International dialling code: 0081 Recent history, culture Held in the city of Annaka, the Ansei Tooashi Samurai Marathon is most likely the oldest marathon of Japan. Back in 1855 a local lord organised a race between his troops and the name of the finishers was recorded in the order of arrival. Today the peculiarity of this marathon is that participants are dressed in costumes of any kinds, from wearing samurai armour, running as an anime or video game character, dressed like Santa Claus or even a vegetable there is no limit to participants’ imagination to make the event a joyful one. [3] Economic overview Gunma Prefecture, home to large corporations such as Fuji Heavy Industries (known for its Subaru cars), Sanyo Electric, and Sanden Corporation, is known as an automotive and electrical equipment industry hub. -

“Art Destination” Shiroiya Hotel Opens in Maebashi, Japan

PRESS RELEASE Minako Morita December 21, 2020 Public Relations [email protected] +81-(0)70-3858-7580 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE “ART DESTINATION” SHIROIYA HOTEL OPENS IN MAEBASHI, JAPAN [MAEBASHI, GUNMA, December 2020] — SHIROIYA HOTEL Inc. (Maebashi City, Gunma Prefecture, Japan, CEO Ko Yamura) is pleased to announce the opening of its new art-inspired hotel, SHIROIYA HOTEL, on December 12, 2020. As of November 4, 2020, the hotel has begun accepting accommodation and restaurant reservations. For reservations, visit www.shiroiya.com Photos: Katsumasa Tanaka (left) / Shinya Kigure (right) The birth of the SHIROIYA HOTEL began with an ambition to revitalize central Maebashi. The new SHIROIYA HOTEL will occupy the grounds of the former Shiroiya Ryokan (Japanese Inn), which closed permanently after hosting guests in Maebashi for over 300 years. Maebashi is a former silk- manufacturing city that greatly contributed to Japan's modernization. The new SHIROIYA HOTEL will be reborn as the “city’s living room” — a destination inspired by art and culinary culture where local residents and travelers can mingle. In August 2016, Maebashi City announced its new vision for the future to become a place "Where Good Things Grow." Following the promulgation, new innovative shops and communities began emerging in the city, largely contributing to the city’s revitalization. The “Maebashi Model” quickly became well-known as a model for the revitalization of medium sized cities. SHIROIYA HOTEL sits at the heart of the city center and will serve as an “art destination,” a place of inspiration for people visiting the area. SHIROIYA HOTEL is designed by Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto. -

00006 Hori Folk Religion in Japan.Pdf

HASKELL FOLK LECTURES RELIGION ON IN HISTORY JAPAN OF Continuity md Clwnge RELIGIONS NEW SERIES ICHIRO HORI No. 1 EDITED BY Joseph M. Kitagawa and Alan L. Miller z-a THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS JOSEPH M. KITAGAWA, General Editor Chicago and London The woodcuts in this book are from: Thomas W. Knox, ome time ago, H. I. H. Prince Takahito Mi- Adventures of Two Youths in a Iourney to lapan and China f4cEcEG S kasa characterized Japan as a “living laboratory and a liv- (Harper and Brothers), 1880. ing museum to those who are interested in the study of history of religions.” Visitors to Japan will find the countryside dotted with Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. In the big cities, too, one finds various kinds of The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian establishments, as well The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London as those of the so-called new religions, which have mush- 0 1968 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved Published 1968. Third Impression 1974 roomed since the end of World War II. Indeed, even in Printed in the United States of America the modem industrialized Japan, colorful religious festi- ISBN: O-226-35333-8 (clothbound) ; O-226-35334-6 (paperbound) vals and pilgrimages play important parts in the life of Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 67-30128 the people. Historically, the Japanese archipelago, being situated off the Asiatic continent, was destined to be influenced by a number of religious and semi-religious traditions from abroad, such as Confucianism, Taoism, Yin-yang school, Neo-Confucianism, various forms of Buddhism and Christianity, as well as all kinds of magical beliefs and practices. -

Motorcycle Tour, Symbol of Japan's Tour Kanto Motorcycle Tour, Symbol of Japan's Tour Kanto

Motorcycle tour, Symbol of Japan's Tour Kanto Motorcycle tour, Symbol of Japan's Tour Kanto Duration Difficulty Support vehicle כן días Easy 7 Language Guide כן en The trip of a lifetime. Dogashima’s wonderful nature and relaxing hot spring, breathtaking view from the Ashinoko Skyline and Mount Fuji, the symbol of Japan, will be some of the main features included in this iconic motorcycle tour. This tour is specifically made not only to let you enjoy motorcycle touring in Japan, but also some unique pieces of Japanese culture as well. You of course will enjoy classic Japanese pattern like hot spring’s relaxing water and made fresh sashimi, but you will also be able to try the uncommon experience of wasabi’s harvest on an authentic Japanese wasabi field. You will be also enjoying some of the greatest historic treasures Japan can offer you, like the Owakudani valley or the unique Oshino Hakkai. And then, the road: Izu Skyline’s curves, the Kawazu Nanadaru Bridge’s astonishing loop and the romantic ocean view on the Bay Bridge. You will understand the uniqueness of motorcycle touring in the Land of the Rising Sun. Itinerary 1 - - Tokyo - Briefing and Welcome Party On the day before our departure, our tour guides will hold a brief meeting time to let you enjoy your tour in Japan in with security and fun. They will explain you Japan's riding rulse, peculiarity, Japanese culture and of course your tour schedule in detail. 2 - Odaiba Beach - Hakone - Odaiba → Hakone The start of our journey will be a riding on some of the best panoramic roads in the country, the Ashinoko Skyline, alongside the beautiful Ahinoko Lake and the legendary Izu Skyline, a curvy road dream of any biker.