EASA Safety Information Bulletin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propulsion Systems for Aircraft. Aerospace Education

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 292 SE 014 556 AUTHOR Mackin, T. E. TITLE Propulsion Systems forAircraft. Aerospace Education II. INSTITUTION Air Univ., Maxwell AFB,Ala. Junior Reserve Office Training Corps. SPONS AGENCY Department of Defense,Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 69 NOTE 128p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Education; *Aerospace Technology; *Engines; Instruction; *Physical Sciences; *Resource Materials; Supplementary Textbooks; Textbooks ABSTRACT The main part of the book centers on the discussion of the engines in an airplane. After describing the terms and concepts of power, jets, and rockets, the author describes the reciprocating engines. The description of diesel engines hejos to explain why these are not used in airplanes. The discussion of the carburetor is followed by a discussion of the lubrication system. Lubrication is an important feature in the smooth functioning of aircraft, not only because of lubrication properties butbecause of its complementary role in cooling down the heat released in engines. The chapter on reaction engines describes the operation of the jet in theory and gives examples of how the different types of jet engines operate. Rocket engines are also explained briefly. The book is to be used for the Air Force ROTC program only.. (PS) U.S. OEPARTMENT OFHEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HASBEEN REPRO- OUCEO EXACTLY ASRECEIVED FROM THE PERSON ORORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT POINTS OFVIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED 00 NOTNECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICEOF EOU- CATION POSITION OR POLICY. Air Force Junior ROTC Air University/Maxwell 4ir Force Base, Alabama cl N0- CO AEROSPACE EDUCATION II LLI Propulsion Systemsfor Aircraft T. -

Carburetor Icing and Control

CAVEAT EMPTOR ... (Continued from Preceding Page) facturer allows becaus e harmonith f o e c vibratio- en n tanglements that are set up. Third, to complicate the matter further . whic e proin s pitche th ,4 s pwa hi 6 o dt again way over the manufacturer's limit. With three strikes against it, that prop was bound to go out and it just about took me with it. Carburetor Icing On this subjec f buyino t g e homebuiltpropth r sfo I , ha a dlon g chat with Steve Wittma t Oshkosa n d an h have subsequently talke o t othed r well qualified, knowledgeable people. Base n whado t I've learnedd I' , like to submit these recommendations: 1. If interested in buying a "reconditioned" prop Iml Control from a shop not well-known to you, check with the FAA to find out if they are a certified prop shop. My supplier was not certified. This will not make them liable for an experimental prop that they sell you, but at least they'l e limius l t tables, etc. n makini , youp u g r prop. Get a yellow tag! f 2buyinI . a gpro p fro a mprivat e source, check Shivers,B. ByC. (EAAJr. 49289) with the FAA or other facility to determine that the prop model wile suitablb l r youfo e r purposes. Just 8928 Valleybrook Road becaus t bolfite i th st pattern doesn't mea nthinga . Birmingham, Alabama buyinf - I . de 3 thae s gbrana on propwa t w y dne bu , signed for a similar application to yours. -

Propulsion Systems for Aircraft. Aerospace Education II

. DOCUMENT RESUME ED 111 621 SE 017 458 AUTHOR Mackin, T. E. TITLE Propulsion Systems for Aircraft. Aerospace Education II. INSTITUTION 'Air Univ., Maxwell AFB, Ala. Junior Reserve Office Training Corps.- PUB.DATE 73 NOTE 136p.; Colored drawings may not reproduce clearly. For the accompanying Instructor Handbook, see SE 017 459. This is a revised text for ED 068 292 EDRS PRICE, -MF-$0.76 HC.I$6.97 Plus' Postage DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace 'Education; *Aerospace Technology;'Aviation technology; Energy; *Engines; *Instructional-. Materials; *Physical. Sciences; Science Education: Secondary Education; Textbooks IDENTIFIERS *Air Force Junior ROTC ABSTRACT This is a revised text used for the Air Force ROTC _:_progralit._The main part of the book centers on the discussion -of the . engines in an airplane. After describing the terms and concepts of power, jets, and4rockets, the author describes reciprocating engines. The description of diesel engines helps to explain why theseare not used in airplanes. The discussion of the carburetor is followed byan explanation of the lubrication system. The chapter on reaction engines describes the operation of,jets, with examples of different types of jet engines.(PS) . 4,,!It********************************************************************* * Documents acquired by, ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other souxces. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copravailable. nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document" Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original. -

Multi Engine Systems

Nice Air Operation Procedure PA-34 Seneca 1 Multi engine systems PA 34-200 Seneca Engine Make : Avco Lycoming Model: Right Engine LIO-360 C1E6(turning counter clockwise from the cockpit) Left Engine IO-360 C1E6 Type: • 4 cylinders • Horizontally opposed • Normally aspirated(No turbo charge) • Air cooled (Engine oil and fuel helps cooling) • Direct drive(Propeller is attached to the crank shaft directly without any reduction gear or trans- mission) • Fuel injected Horsepower: 200 BHP Alternate air: Working as a carburetor heat. Heated air around exhaust manifold is directed through the alternate air source. RPM drops slightly when it is open. Cowl flap: Manually operated. There are three positions; open, half and closed. Propeller Make: Hartzell Model: Type: Constant speed, full feathering propeller What is a constant speed prop? The propeller which maintains the RPM selected by propeller control lever constant regardless of air- plane’s pitch attitude or throttle position within some range. The advantage of a constant speed prop. The pilot can select the most efficient blade angle for each phases of operation. By selecting low pitch/ high RPM, you can get maximum power for takeoff. By selecting high pitch/low RPM, you can fly faster at low RPM and you can save the fuel for cruise. How does it work? When the airplane rise it’s nose, it start climb. As it climb, airspeed goes down. The RPM is also going Copy Right Nice Air 2575 Robert Fowler Way, San Jose, CA 95148 Phone(408)729-3383 Nice Air Operation Procedure PA-34 Seneca 2 down due to increasing drag on the blade. -

Opel 1900Cc Engines: Tuning & Vacuum Notes

Opel 1900cc Engines: Tuning & Vacuum Notes Spark Plugs Ignition Wire Set 4 Opel engines require proper fuel, compression, correct ignition timing & spark. 3 Tuning to correct specifications, will maximize your power output. 2 1 IGNITION Verify voltage is present at the “+” terminal in the ignition coil, and check for a spark at each plug (when cranking). Mis-fires can be difficult to diagnose (particularly when they occur intermittently), so always start with all new parts. Important Specifications Ignition Coil Distributor: Set at zero degrees TDC (with vacuum lines plugged), at low idle Avoid excessive advance (detonation damages pistons & rings) Check “indentation shape” on cap edge (to identify style) Point Gap: Set at .018” & verify 50 degree (+/- 2º) “dwell” measurement Spark Plug Gap: Set at .030” Recommended Firing Order: 1-3-4-2 Replace all maintenance items with new parts (clockwise) Distributor Cap & Rotor #6041 Ignition Point Set #6042 Point set & Condenser can be Condenser #6043 (or Module #6165) replaced w/electronic ignition Spark Plugs #6040, 6163, 6175 Ignition Wire Set #6071 #6165 for better driveability ! Camshaft “Ball” along outer edge of cam gear “Ball” on flywheel #4 #2 (aligns to notch through center) Timing aligns to pointer “Dowel Pin” on camshaft #1 TDC Rotor sprocket is at “6 o’clock” “Dowel” mark (and “ball mark” #3 #1 on outer edge “Notch” in plate of gear needs Rotor points to #1 TDC Mark, to align to “notch” located on outer edge of in curved metal support plate, Engine: Rear Passenger Side distributor housing when measured through center of the cam gear). -

Fuel Injection Vs. Carburetor

Fuel Injection Vs. Carburetor Advantages and disadvantages of the two fuel supply systems a1'e analyzed. Carburetor-icing bugaboo n/,ay have been overemphasized tain a proper mixture, it is necessary to vary the now Incussiongeneralcurrentlyaviation oncirclesthe subjectthere is ofconsiderablethe merits dis•of of fuel with r.p.m. and with buttertly opening. This fuel injection, The general aviation public has evi• means a linkage of the fuel injector pump with an dently seized on fuel injection as a very desirable im• engine gear, as well as a connection with the buttertly provement over the carburetor, The public, along with through the throttle. All of this gets a little compli• some members of industry, often has a tendency to• cated, requires extra mechanism and fairly high pres• wards overemphasizing the value of a departure from sure. the standard, without due knowledge or consideration The carburetor, in which fuel is mixed with ail' simply of the facts. Frequently, after the various factors be• by the suction of air tlowing through the venturi, re• come apparent, the advantages of the previous stand• quires only a minimum of fuel pressure, and is about ard bring it back into public favor. This may well be as simple and trouble-free an arrangement as could be the case in the present controversy of fuel injection devised. versus the carbu retor, The advantages of the fuel injector are: My own preference, after having carefully investi• (Continued Oil p"ge .50) gated both types of fuel metering systems, is for the carburetor, at least on aircraft up to and including those of the complexity of the Aztec, and on the types of engines that are used in these models. -

Carb Ice: the Threat and the Theory

independent SERVICE CENTRE AIRCRAFT ENGINES Part # 44 Carb Ice: The Threat And The Theory 8. Inversion layers may exist whereby icing conditions are more in evidence than lower down, so we can climb by Mike Stratman with plenty of power and suddenly experience icing in an inversion. In the East inversions can be any height in a high pressure system (clear cool day). In a low with Dennis Pagen pressure system inversions don’t usually occur, but plenty of humidity abounds so icing can be a problem. Throttling back from cruise you set up a long glide to In the West, inversions are more likely due to local ef- your home field in the distance. As you descend you can fects and terrain allowing different layers of air to move feel the air change temperature as you pass into a new into an area. Whether or not these inversions present inversion layer. The air is now cool and moist. After several an icing problem depends on where the air mass origi- minutes the engine starts to lose rpm, you increase the nates. The generally drier air in the West reduces the throttle setting without a response. The engine begins to problem greatly. run rough and shake. You work the throttle furiously to no 9. Ice forms for two reasons: drop in temperature due to avail. Despite your best efforts the engine quits. Have you the drop in pressure in the venturi (about a 5 degree just been a victim of Carb Ice? drop in temp) and due to evaporation of gasoline as For years the debate on the facts and fiction surround it mixes with air (this drop can be 60F or more) The Carb Ice in Rotax engines has raged. -

GO-480, IGO-480, GSO-480 and IGSO-480 Series OperatorS Manual Lycoming Part Number: 60297-14

Operators Manual Lycoming GO-480, IGO-480, GSO-480 and IGSO-480 Series Approved by FAA 3rd Edition Part No. 60297-14 July 2008 652 Oliver Street Williamsport, PA. 17701 U.S.A. 570/323-6181 GO-480, IGO-480, GSO-480 and IGSO-480 Series Operators Manual Lycoming Part Number: 60297-14 ©2008 by Lycoming. All rights reserved. Lycoming and Powered by Lycoming are trademarks or registered trademarks of Lycoming. Lycoming Engines, a division of AVCO Corporation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Textron Inc. All brand and product names referenced in this publication are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective companies. For additional information: Mailing address: Lycoming Engines 652 Oliver Street Williamsport, PA 17701 U.S.A. Phone: Factory: 570-323-6181 Sales Department: 570-327-7268 Fax: 570-327-7101 Lycomings regular business hours are Monday through Friday from 8:00 AM through 5:00 PM Eastern Time (-5 GMT) Visit us on the World Wide Web at: http://www.lycoming.com LYCOMING OPERATORS MANUAL ATTENTION OWNERS, OPERATORS, AND MAINTENANCE PERSONNEL This operators manual contains a description of the engine, its specifications, and detailed information on how to operate and maintain it. Such maintenance procedures that may be required in conjunction with periodic inspections are also included. This manual is intended for use by owners, pilots and maintenance personnel responsible for care of Lycoming powered aircraft. Modifications and repair procedures are contained in Lycoming overhaul manuals; maintenance personnel should refer to these for such procedures. SAFETY WARNING Neglecting to follow the operating instructions and to carry out periodic maintenance procedures can result in poor engine performance and power loss. -

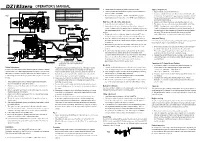

Dz185zero OPERATOR's MANUAL 2

DZ185zero OPERATOR'S MANUAL 2. Please check and retighten propeller locknut periodically. Tappets Adjustment Bore 35mm Plug Cap Screw 3. Select a propeller that will allow the engine to run at a maximum of 1. Tappet clearance is pre-set at the factory. 136.5 Stroke 31.8mm 119.4 between 6,000 to 8,000 RPM. 2. Clearance adjustment may need after one hour of running time due Weight 965g ( Engine, Plug) 4. We recommend sizes 19x11, 20x10.5, 20.5x10. Other propeller FIG 1 100g ( Ignition Box) to initial wear. After adjustment, tappet clearance should be checked Displacement 30.6cc sizes may be used as long as the correct RPM range is maintained. during normal maintenance after every 10 hours of running to main Practical rpm 1,000~9,000rpm tain maximum performance. High Speed Needle Valve Adjustment 3. Clearance adjustment should be done when the engine is cool. 57 58 68.6 1. An electric starter is mandatory for this engine. 4. The proper clearance setting is between 0mm (0.000”) and 0.1mm Battery(4.8~8.4V) Switch 2. Turning the needle valve clockwise leans the mixture. Turning it (0.004”). The adjustment is achieved by loosening the locknut Red couner-clockwise richens the mixture. A good starting position for the (“Fig.2”) and turning the adjustment screw. The engine must be at high speed needle valve is 1 and 1/2 turns open from the fully closed top dead center on the compression stroke before any adjustments 63 25 14 postion. are made. This engine runs best with the valves set at a tight Ignition Box Red Black 3. -

GENERAL INFORMATION on These Vehicles, the Engine Management System Is Considered Part of the Emission Control System. the Majo

GENERAL INFORMATION On these vehicles, the engine management system is considered part of the emission control system. The major components include the carburetor(s), feedback control system, the air injection system, a throttle control system and the EGR system. The system consists of sensors and switches that feed information to the Electronic Control Unit (ECU), which will then operate several solenoid valves to maintain the ideal air/fuel ratio under all conditions. As useful as the tests found in this section are, the first step in repair or service to engine management systems is still to gain as much information as possible about the problem; when and under what conditions it occurs. At highway speed? At idle only? Only under heavy load or hard acceleration? Wet weather? Defining the problem will eliminate many systems from consideration and possibly point to the affected system. Before diving into an extended electrical diagnosis, take the time to review the basics. Check every vacuum line for cracks or leaks. Check every electrical connector for corrosion or loose pins. Quite often, simply unplugging and reconnecting a connector will break up corrosion on the pins and restore the circuit. Watch out for poor grounds, particularly if the car has experienced major bodywork. COMPONENT TESTING carbureted Accords Related Air Injection System The purpose of this system is to supply oxygen to the exhaust stream at a point in the exhaust manifold that is hot enough to burn off some of the hydrocarbon emissions. The main component is an air suction valve. The valve is spring loaded to stay closed, with engine vacuum supplied to a diaphragm that reduces the spring pressure and allows the reeds to open. -

Rewritten and Combined with Article “Induction Icing” the Gasoline

controllable-pitch propeller is used. In either case, a loss of altitude or airspeed will occur. These symptoms may sometimes be accompanied by vibration or engine roughness. In any case, it is a good idea to consider carburetor ice as the cause of any unexplained power loss during cruise flight. Rewritten and combined with article “Induction Icing” Once a power loss is noticed by the pilot, immediate action should be taken to eliminate ice which has already formed in the carburetor, and The gasoline engine operates on a fuel/air mixture that is ignited by the spark to prevent further ice formation. This is accomplished by applying plugs. Engines do not run when any of these elements are missing. Pilots know full carburetor heat which will initially cause a further loss of power positively that they must refuel the aircraft on a regular basis if they want to fly (perhaps as much as 15%) and possibly, engine roughness. The without incident, but the possibility of losing the air part of the fuel/air mixture additional power loss is caused by the heated air that is being directed is not always considered and understood as well as it should be. Perhaps the into the induction system. Heated air makes the mixture richer and personal experience of several individuals, and some facts about induction- also melts the ice which then goes through the engine as water. The system icing can be used to help Flyer readers avoid an accident caused by lack throttle may be advanced and the mixture may be leaned to help get of air for their engines. -

Advisory Circular

Advisory Circular Subject: Inspection and Care of General Date: 7/23/07 AC No: 91-59A Aviation Aircraft Exhaust Systems Initiated by: AFS-300 1. PURPOSE. a. This advisory circular (AC) emphasizes the safety hazards of poorly maintained aircraft exhaust systems (reciprocating powerplants) and highlights points at which exhaust system failures occur. Further, it provides information on the kinds of problems to be expected and recommends pilots perform ongoing preventive maintenance and mechanics perform maintenance. b. This AC provides an acceptable means of complying with the regulations; however, it is not the only means of compliance. This AC is not mandatory and does not constitute a regulation. When this AC uses mandatory language (e.g., “must” or “may not”) it is paraphrasing a regulatory requirement or prohibition. When this AC uses permissive language (e.g., “should” or “may”), it describes an acceptable means, but not the only means, of complying with regulations. However, if you use the means described to comply with a regulatory requirement, you must follow it in all respects. 2. CANCELLATION. AC 91-59, Inspection and Care of General Aviation Aircraft Exhaust Systems, dated August 20, 1982, is canceled. 3. RELATED READING MATERIALS (current editions). a. AC 20-32, Carbon Monoxide (CO) Contamination in Aircraft Detection and Prevention. b. AC 20-106, Aircraft Inspection for the General Aviation Aircraft Owner. c. AC 43-12, Preventive Maintenance. d. AC 43.13-1, Acceptable Methods, Techniques, and Practices—Aircraft Inspection and Repair. e. AC 43-16, General Aviation Airworthiness Alerts. f. AC 65-12, Airframe and Powerplant Mechanics Powerplant Handbook.