Building Resilient Communities Summary Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of Privacy Practices KAISER PERMANENTE—NORTHWEST REGION Notice of Privacy Practices THIS NOTICE DESCRIBES HOW MEDICAL A

Notice of Privacy Practices KAISER PERMANENTE—NORTHWEST REGION Notice of Privacy Practices THIS NOTICE DESCRIBES HOW MEDICAL AND DENTAL HEALTH INFORMATION ABOUT YOU MAY BE USED AND DISCLOSED AND HOW YOU CAN GET ACCESS TO THIS INFORMATION. PLEASE REVIEW IT CAREFULLY. In this notice we use the terms "we," "us," "our," and "Kaiser Permanente" to describe the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region. For more details, please refer to section IV of this notice. I. What is "Protected Health Information?" Your protected health information (PHI) is individually identifiable health information, including demographic information, about your past, present or future physical or mental health or condition, health care services you receive, and past, present or future payment for your health care. Demographic information means information such as your name, social security number, address, and date of birth. PHI may be in oral, written or electronic form. Examples of PHI include your medical record, claims record, enrollment or disenrollment information, and communications between you and your health care provider about your care. Your individually identifiable health information ceases to be PHI 50 years after your death. If you are a Kaiser Foundation Health Plan of the Northwest member and also an employee of any Kaiser Permanente company, PHI does not include the health information in your employment records. II. About our responsibility to protect your PHI By law, we must 1. protect the privacy of your PHI; 2. tell you about your rights and our legal duties with respect to your PHI; 3. notify you if there is a breach of your unsecured PHI; and 4. -

Twenty-Four/Sevenoctober 18, 2010 Volume 5, Issue 23

October 18, 2010 Volume 5, Issue 23 CLARKtwenty-four/seven CLARKtwenty-four/seven Table of Contents October 18, 2010 Notes from the Smiles All Around Meet Your New Upcoming Events 2 Summit White 5 Dental Hygiene 7 Ambassadors! 12 House Summit on Anniversary Student Community Colleges Ambassadors From the HR A Voice from History 13 Department Breakfast for 6 David Hilliard speaks Penguin Patter 3 Champions on Black Panthers 10 News about people Advisory Committee from throughout the recognition Penguin Nation! Cover: Dean of Health Sciences Blake Bowers 2 and Associate Director of Instructional Operations Dedra Daehn attend the Advisory Committee Recognition Breakfast on Friday, October 15. 5 14 3 1 Notes from the Summit Clark hosts webcast of first-ever White House Summit on Community Colleges. “Community colleges are the unsung heroes of higher education.” That was a key message as President Obama convened the first White House Summit on Community Colleges on Tuesday, October 5. The event was led by Dr. Jill Biden, who has been a community college professor for 17 years. Among the highlights: • The administration has announced a new partnership called “Skills for America’s Future.” It’s designed to change the way business and labor leaders connect to community colleges. • President Obama has set a goal for America to once again lead the world in producing college graduates by 2020. That includes an additional 5 million community college degrees and certificates in the next 10 years. • The Bill and Melinda Gates foundation are launching the “Completion by Design” program. Investing $35 million over five years, the program hopes In a phrase that has special meaning at Clark College, two of the speakers— to dramatically improve graduation rates at community colleges. -

Kaiser Permanente Find Your Healthy Place

2021 Enrollment | California Find your healthy place With care designed to help you thrive kp.org/thrive Primary care Health Specialty plan care Digital care Pharmacy options and labs Connected care makes your life easier We combine care and coverage — which makes us different than your other health care options. Your doctors, hospitals, and health plan work together to make getting the right care more convenient. Your care meets you where you are, because it’s centered around you. 2 Benefit Summary 603910 UNITE HERE HEALTH - NCAL Principal Benefits for Kaiser Permanente Traditional HMO Plan (1/1/21—12/31/21) Accumulation Period The Accumulation Period for this plan is January 1 through December 31. Out-of-Pocket Maximum(s) and Deductible(s) For Services that apply to the Plan Out-of-Pocket Maximum, you will not pay any more Cost Share for the rest of the Accumulation Period once you have reached the amounts listed below. Family Coverage Family Coverage Self-Only Coverage Amounts Per Accumulation Period Each Member in a Family of Entire Family of two or more (a Family of one Member) two or more Members Members Plan Out-of-Pocket Maximum $2,000 $2,000 $4,000 Plan Deductible None None None Drug Deductible None None None Professional Services (Plan Provider office visits) You Pay Most Primary Care Visits and most Non-Physician Specialist Visits .......................... $20 per visit Most Physician Specialist Visits................................................................................. $20 per visit Routine physical maintenance exams, including well-woman exams ........................ No charge Well-child preventive exams (through age 23 months) .............................................. No charge Family planning counseling and consultations.......................................................... -

Medicalkaiserperm00smilrich.Pdf

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program Oral History Project John G. Smillie, M.D. HISTORY OF THE KAISER PERMANENTE MEDICAL CARE PROGRAM An Interview Conducted by Ora Huth in 1985 Copyright (cj 1987 by The Regents of the University of California All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and John G. Smillie, M.D. dated March 28, 1985. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes . All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to the Regional Oral History Office, 486 Library, and should include identification of the specific passages to be quoted, anticipated use of the passages, and identification of the user. The legal agreement with John G. Smillie, M.D. requires that he be notified of the request and allowed thirty days in which to respond. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows : John G. Smillie, M.D., "History of the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program," an oral history conducted in 1985 by Ora Huth, Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 1987. Copy No. JOHN G. SMILLIE, M.D. TABLE OF CONTENTS John G. -

2017/2018 Annual Report

2017/2018 ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Annual Report 092718.indd 1 10/1/18 10:02 AM The 2017 – 2018 fiscal year has proven to be Oakland Parks and Recreation Foundation’s most productive to-date. Though the effective leadership of our Executive Director, Ken Lupoff, as well as the tireless work of our board members, the Foundation hit some major milestones this past year. One of our major accomplishments was with our 15th Annual A Taste of Spring in April. Through diligent work and effective planning, we were able to not only hold the event at the Oakland Museum of California for the first time, but also produced record net revenue for our signature event. It proved to be a special evening with a room full of great energy. We sincerely thank all who were able to join us at this year’s A Taste of Spring and we appreciate the generosity of our attendees. As the Foundation is always working on creative ways to fundraise, we recently started holding private house parties which are designed to introduce Oakland Parks and Recreation Foundation to potential new supporters. This new venture has been a true success, and we are currently planning our next party as well as others over the course of the next year. On the volunteerism front, we have really stepped up our game! Led by our Vice President and Volunteerism Committee Chair, Liz Westbrook, our volunteer work has grown in scope over the past year, as we now typically conduct three to four solid work days per year. -

2016 Community Health Needs Assessment

2016 Community Health Needs Assessment Kaiser Foundation Hospital – Oakland and Kaiser Foundation Hospital – Richmond License #140000052 Approved by KFH Board of Directors September 21, 2016 To provide feedback about this Community Health Needs Assessment, email [email protected] i KAISER PERMANENTE NORTHERN CALIFORNIA REGION COMMUNITY BENEFIT CHNA REPORT FOR KFH-OAKLAND AND KFH-RICHMOND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by Applied Survey Research (ASR) on behalf of the hospitals listed in this report. ASR gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following individuals: Diana Camacho, John Muir Health Molly Bergstrom, Kaiser Permanente – Diablo Area Jean Nudelman, Kaiser Permanente – East Bay Area Debra Lambert, Kaiser Permanente – Greater Southern Alameda Area Michael Cobb, St. Rose Hospital Sue Fairbanks, San Ramon Regional Medical Center Karen Reid, San Ramon Regional Medical Center Tim Traver, San Ramon Regional Medical Center Denise Bouillerce, Stanford Health Care – ValleyCare Shelby Salonga, Stanford Health Care – ValleyCare Adam Davis, UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland Lucy Hernandez, Washington Hospital Healthcare System Ruth Traylor, Washington Hospital Healthcare System ASR is also pleased to acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals: Dale Ainsworth, California State University, Sacramento Marianne Balin, Kaiser Permanente – Diablo Area Debi Ford, San Ramon Regional Medical Center Susan Miranda, Kaiser Permanente – Greater Southern Alameda Area Dana Williamson, -

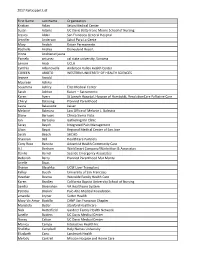

2017 Participant List First Name Last Name Organization Kristian Aclan

2017 Participant List First Name Last Name Organization Kristian Aclan Seton Medical Center Susan Adams UC Davis Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing Jessica Aldaz San Francisco General Hospital Jennifer Anderson Salud Para La Gente Mary Andich Kaiser Permanente Rochelle Andres Disneyland Resort Irinna Andrianarijaona Pamela antunez cal state university, Sonoma Lenore Arab UCLA Cynthia Arbanovella Anderson Valley Health Center COREEN ARIOTO WESTERN UNIVERSITY OF HEALTH SCIENCES Jeanne Arnold Maureen Ashiku Sosamma Ashley Elite Medical Center Sarah Ashton Kaiser -- Sacramento Karen Ayers St Joseph Hospital, Hospice of Humboldt, ResolutionCare Palliative Care Cheryl Balaoing Planned Parenthood Laura Balassone kaiser Melanie Balestra Law Office of Melanie L. Balestra Diane Barrows Clinica Sierra Vista Jan Bartuska Gathering Inn Clinic Seray Bayoh Integrated Pain Management Lilian Bayot Regional Medical Center of San Jose Sarah Beach SHCHD Shannon Bell HealthCare Partners Cony Rose Bencito Adventist Health Community Care A.J. Benham WorkSmart Company/Warbritton & Associates Danilo Bernal Seaside Emergency Associates Deborah Berry Planned Parenthood Mar Monte Arielle Bivas Sharon Blaschka UCSF Liver Transplant Kelley Booth University of San Francisco Heather Bosma Westside Family Health Care Karen Bradley California Baptist University School of Nursing Sandra Bresnahan VA Healthcare System Patricia Briskin` Palo Alto Medical Foundation amanda bryner Sutter Health Mary Vic Amor Bustillo CANP San Francisco Chapter Maristela Butler Stanford Healthcare -

2018 Leapfrog Top General Hospitals

2018 LEAPFROG TOP GENERAL HOSPITALS California Illinois Riverview Medical Center Inland Valley Medical Center Elmhurst Memorial Hospital Inspira Medical Center Woodbury Kaiser Foundation Hospital - Antioch Northwestern Medicine Delnor Rancho Springs Medical Center Hospital Pennsylvania Sequoia Hospital UPMC East Kaiser Foundation Hospital - San Louisiana Leandro St. Charles Parish Hospital Tennessee Adventist Health – Bakersfield TriStar Southern Hills Medical Center Massachusetts Florida Holy Family Hospital at Merrimack Texas Florida Hospital Apopka Valley Methodist Richardson Medical Center Jupiter Medical Center Saint Anne's Hospital Medical City Denton Florida Hospital Zephyrhills Kingwood Medical Center Florida Hospital Wesley Chapel Nevada CHRISTUS Mother Frances Hospital – Florida Hospital Carrollwood Henderson Hospital Tyler Orlando Health Dr. P. Phillips Hospital St. Mary's Regional Medical Center of Memorial Hospital West Reno Virginia Lawnwood Regional Medical Center & Inova Alexandria Hospital Heart Institute New Jersey Bon Secours Mary Immaculate Memorial Hospital Miramar Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Florida Hospital Heartland Medical Hospital at Hamilton Center Bayshore Medical Center 2018 LEAPFROG TOP CHILDREN’S HOSPITALS Arizona Florida Texas Phoenix Children’s Hospital Golisano Children’s Hospital of Children’s Health - Children’s Medical Southwest Florida Center Plano California Wolfson Children’s Hospital Texas Children’s Hospital West Loma Linda University Children’s Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Campus -

Academic Catalog

Kaiser Permanente School of Allied Health Sciences 2020 Academic Catalog Effective Dates: January 1, 2020 – December 31, 2020 2020 Academic Catalog (v.2020-09-21) p. 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................................... 2 About this Catalog ......................................................................................................................................... 4 General Information ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Mission, Vision, Values Statements .............................................................................................................. 6 Public Good Statement ................................................................................................................................. 7 Institutional Learning Outcomes................................................................................................................... 7 Accreditation and Approvals ......................................................................................................................... 8 Facilities and Equipment ............................................................................................................................. 10 General Education ...................................................................................................................................... -

The Story of Dr. Sidney R. Ga R Field

GarfieldCoverFINAL.pdf 3/17/09 9:48:53 AM How one physician’s revolutionary vision paved the way from a 12-bed hospital in the Mojave Desert at the height of the Great Depression to what is today the nation’s largest, most successful THE STORY OF nonprot health care organization — Kaiser Permanente. Like the architect he always wanted to be, physician Sidney R. Gareld spent most of his life designing and building a model of a new kind of health care. Built on the foundations of group practice (as opposed to solo practice), prepayment (as opposed to fee-for-service), and prevention and health promotion (as opposed to sick care only), it was in many ways the opposite, mirror-image of the way health care was nanced and delivered in the rest of America. In partnership with Henry J. Kaiser, one of the great industrialists of the early 20th century, Gareld stood rm against waves of early opposition from mainstream medicine and went on DR. SIDNEY R. GA to build one of the most acclaimed and successful health care organizations in America. This book tells the story of Dr. Sidney Gareld’s long and eventful career in turning his desert dream into a thriving and enduring reality that continues to oer a practical model for the future of American health care. C M Words from Permanente Medical Leaders Y CM Thank you for the advance copy of your new Dr. Gareld was a remarkable man and this R MY book on Dr. Gareld. I could not stop reading book does an excellent job of chronicling his FIELD CY it until I had nished it all. -

C. Air Quality

IV. Environmental Setting, Impacts and Mitigation Measures C. Air Quality This section discusses the potential impacts of the implementation of the Kaiser Permanente OMC Project on the local and regional air quality. As necessary, appropriate standard conditions of approval are also identified and discussed. Setting Regulatory Framework EPA is responsible for implementing the programs established under the federal Clean Air Act, such as establishing and reviewing the federal ambient air quality standards and judging the adequacy of State Implementation Plans (SIP). However, the EPA has delegated the authority to implement many of the federal programs to the states while retaining an oversight role to ensure that the programs continue to be implemented. In California, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) is responsible for establishing and reviewing the state ambient air quality standards, developing and managing the California SIP, securing approval of this plan from U.S. EPA, and identifying TACs. (A notable exception exists for radioactive air contaminants as the EPA has retained its authority to enforce NESHAP requirements.) CARB also regulates mobile emissions sources in California, such as construction equipment, trucks, and automobiles, and oversees the activities of air quality management districts, which are organized at the county or regional level. An air quality management district is primarily responsible for regulating stationary emissions sources at facilities within its geographic areas and for preparing the air quality plans that are required under the federal Clean Air Act and California Clean Air Act. The Bay Area Air Quality Management District (BAAQMD) is the regional agency with regulatory authority over emission sources in the Bay Area, which includes all of San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, and Napa counties and the southern half of Sonoma and southwestern half of Solano counties. -

Oakland CHNA

2019 Community Health Needs Assessment Kaiser Foundation Hospital: Oakland License number: 140000052 Approved by Kaiser Foundation Hospital Board of Directors’ Community Health Committee September 16, 2019 Kaiser Permanente Northern California Region Community Benefit CHNA Report for KFH-Oakland Contents I. Introduction/background ........................................................................................................ 1 A. About Kaiser Permanente (KP) ........................................................................................ 1 B. About Kaiser Permanente Community Health .................................................................. 1 C. Purpose of the Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) Report .......................... 2 D. Kaiser Permanente’s approach to Community Health Needs Assessment ...................... 2 II. Community served ................................................................................................................ 3 A. Kaiser Permanente’s definition of community served ....................................................... 3 B. Map and description of community served ....................................................................... 4 i. Map ................................................................................................................................. 4 ii. Geographic description of the community served .......................................................... 4 iii. Demographic profile of the community served .............................................................