Unthinkable Duvalier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election-Violence-Mo

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF IMMIGRATION REVIEW IMMIGRATION COURT xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx In the Matter of: IN REMOVAL PROCEEDINGS XX YYY xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx DECLARATION OF ZZZZZZ I, ZZZZZ, hereby declare under penalty of perjury that the following statements are true and correct to the best of my knowledge. 1. I do not recall having ever met XX YYY in person. This affidavit is based on my review of Mr. YYY’s Application for Asylum and my knowledge of relevant conditions in Haiti. I am familiar with the broader context of Mr. YYY’s application for asylum, including the history of political violence in Haiti, especially surrounding elections, attacks against journalists and the current security and human rights conditions in Haiti. Radio in Haiti 2. In Haiti, radio is by far the most important media format. Only a small percentage of the population can afford television, and electricity shortages limit the usefulness of the televisions that are in service. An even smaller percentage can afford internet access. Over half the people do not read well, and newspaper circulation is minuscule. There are many radio stations in Haiti, with reception available in almost every corner of the country. Radios are inexpensive to buy and can operate without municipal electricity. 3. Radio’s general importance makes it particularly important for elections. Radio programs, especially call-in shows, are Haiti’s most important forum for discussing candidates and parties. As a result, radio stations become contested ground for political advocacy, especially around elections. Candidates, officials and others involved in politics work hard and spend money to obtain favorable coverage. -

Directors Fortnight Cannes 2000 Winner Best Feature

DIRECTORS WINNER FORTNIGHT BEST FEATURE CANNES PAN-AFRICAN FILM 2000 FESTIVAL L.A. A FILM BY RAOUL PECK A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE JACQUES BIDOU presents A FILM BY RAOUL PECK Patrice Lumumba Eriq Ebouaney Joseph Mobutu Alex Descas Maurice Mpolo Théophile Moussa Sowié Joseph Kasa Vubu Maka Kotto Godefroid Munungo Dieudonné Kabongo Moïse Tshombe Pascal Nzonzi Walter J. Ganshof Van der Meersch André Debaar Joseph Okito Cheik Doukouré Thomas Kanza Oumar Diop Makena Pauline Lumumba Mariam Kaba General Emile Janssens Rudi Delhem Director Raoul Peck Screenplay Raoul Peck Pascal Bonitzer Music Jean-Claude Petit Executive Producer Jacques Bidou Production Manager Patrick Meunier Marianne Dumoulin Director of Photography Bernard Lutic 1st Assistant Director Jacques Cluzard Casting Sylvie Brocheré Artistic Director Denis Renault Art DIrector André Fonsny Costumes Charlotte David Editor Jacques Comets Sound Mixer Jean-Pierre Laforce Filmed in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Belgium A French/Belgian/Haitian/German co-production, 2000 In French with English subtitles 35mm • Color • Dolby Stereo SRD • 1:1.85 • 3144 meters Running time: 115 mins A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE 247 CENTRE ST • 2ND FL • NEW YORK • NY 10013 www.zeitgeistfilm.com • [email protected] (212) 274-1989 • FAX (212) 274-1644 At the Berlin Conference of 1885, Europe divided up the African continent. The Congo became the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium. On June 30, 1960, a young self-taught nationalist, Patrice Lumumba, became, at age 36, the first head of government of the new independent state. He would last two months in office. This is a true story. SYNOPSIS LUMUMBA is a gripping political thriller which tells the story of the legendary African leader Patrice Emery Lumumba. -

Haiti 2013 Human Rights Report

HAITI 2013 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Haiti is a constitutional republic with a multi-party political system. President Michel Martelly took office in May 2011 following a two-round electoral process that, despite some allegations of fraud and irregularities, international observers deemed generally free and fair. The government did not hold partial Senate and local elections, delayed since October 2011, because of a continuing impasse between the executive, legislative, and judicial branches over the proper procedures to establish and promulgate an elections law and to organize elections. Authorities maintained effective control over the security forces, but allegations persisted that at times law enforcement personnel committed human rights abuses. The most serious impediments to human rights involved weak democratic governance in the country; insufficient respect for the rule of law, exacerbated by a deficient judicial system; and chronic corruption in all branches of government. Basic human rights problems included: isolated allegations of arbitrary and unlawful killings by government officials; allegations of use of force against suspects and protesters; overcrowding and poor sanitation in prisons; prolonged pretrial detention; an inefficient, unreliable, and inconsistent judiciary; rape, other violence, and societal discrimination against women; child abuse; allegations of social marginalization of vulnerable populations, including persons with disabilities and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons; and -

Haiti Page 1 of 20

Haiti Page 1 of 20 Haiti Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2001 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 4, 2002 Haiti is a republic with an elected president and a bicameral legislature. The 1987 Constitution remains in force, but many of its provisions are not respected in practice. The political impasse and political violence stemming from controversial results of May 2000 legislative and local elections continued during the year. In May 2000, the Provisional Electoral Council (CEP) manipulated the results of the election to ensure that Fanmi Lavalas (FL) maintained control of the Senate. The opposition parties boycotted July 2000 runoff elections and the November 2000 presidential elections, in which Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected with extremely low voter turnout. President Aristide was sworn in on February 7. During the first half of the year, the international community, including the Organization of American States (OAS), and the country's civil society mediated discussions between the FL and the opposition Democratic Convergence; however, negotiations were not successful and talks were suspended in July following armed attacks on several police stations by unidentified gunmen. On December 17, an unknown number of unidentified gunmen attacked the National Palace in Port- au-Prince; 8 persons reportedly died and 15 persons were injured. Following the attack, progovernment groups attacked opposition members' offices and homes; one opposition member was killed. The 1987 Constitution provides for an independent judiciary; however, it is not independent in practice and remained largely weak and corrupt, as well as subject to interference by the executive and legislative branches. -

Cartographie De L'industrie Haïtienne De La Musique

CARTOGRAPHIE DE L’INDUSTRIE HAÏTIENNE DE LA MUSIQUE Organisation Diversité des Nations Unies des expressions pour l’éducation, culturelles la science et la culture Merci à tous les professionnels de la musique en Haïti et en diaspora qui ont accepté de prendre part à cette enquête et à tous ceux qui ont participé aux focus groups et à la table ronde. Merci à toute l’équipe d’Ayiti Mizik, à Patricio Jeretic, Joel Widmaier, Malaika Bécoulet, Mimerose Beaubrun, Ti Jo Zenny et à Jonathan Perry. Merci au FIDC pour sa confiance et d’avoir cru à ce projet. Cette étude est imprimée gracieusement grâce à la Fondation Lucienne Deschamps. Chambre de Commerce et d’Industrie Textes : Pascale Jaunay (Ayiti Mizik) | Isaac Marcelin (Ayiti Nexus) | Philippe Bécoulet (Leos) Graphisme : Ricardo Mathieu, Joël Widmaier (couverture) Editing: Ricardo Mathieu, Milena Sandler Crédits photos couverture : Josué Azor, Joël Widmaier Firme d’enquête et focus group : Ayiti Nexus Tous droits réservés de reproduction des textes, photos et graphiques réservés pour tous pays ISBN : 978-99970-4-697-0 CARTOGRAPHIE DE L’INDUSTRIE HAÏTIENNE LA MUSIQUE Dépot Légal : 1707-465 2 Imprimé en Haïti CARTOGRAPHIE DE L’INDUSTRIE HAÏTIENNE DE LA MUSIQUE Organisation Diversité des Nations Unies des expressions pour l’éducation, culturelles la science et la culture CARTOGRAPHIE DE L’INDUSTRIE HAÏTIENNE LA MUSIQUE 3 SOMMAIRE I. INTRODUCTION 8 A. CONTEXTE DU PROJET 8 B. OBJECTIFS 8 C. JUSTIFICATION 9 D. MÉTHODOLOGIE 10 1. Enquêtes de terrain 10 2. Focus groups 13 3. Analyse des résultats 13 4. Interviews 14 5. Table-ronde nationale 14 II. -

I Am Not Your Negro

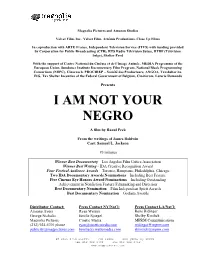

Magnolia Pictures and Amazon Studios Velvet Film, Inc., Velvet Film, Artémis Productions, Close Up Films In coproduction with ARTE France, Independent Television Service (ITVS) with funding provided by Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), RTS Radio Télévision Suisse, RTBF (Télévision belge), Shelter Prod With the support of Centre National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée, MEDIA Programme of the European Union, Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, National Black Programming Consortium (NBPC), Cinereach, PROCIREP – Société des Producteurs, ANGOA, Taxshelter.be, ING, Tax Shelter Incentive of the Federal Government of Belgium, Cinéforom, Loterie Romande Presents I AM NOT YOUR NEGRO A film by Raoul Peck From the writings of James Baldwin Cast: Samuel L. Jackson 93 minutes Winner Best Documentary – Los Angeles Film Critics Association Winner Best Writing - IDA Creative Recognition Award Four Festival Audience Awards – Toronto, Hamptons, Philadelphia, Chicago Two IDA Documentary Awards Nominations – Including Best Feature Five Cinema Eye Honors Award Nominations – Including Outstanding Achievement in Nonfiction Feature Filmmaking and Direction Best Documentary Nomination – Film Independent Spirit Awards Best Documentary Nomination – Gotham Awards Distributor Contact: Press Contact NY/Nat’l: Press Contact LA/Nat’l: Arianne Ayers Ryan Werner Rene Ridinger George Nicholis Emilie Spiegel Shelby Kimlick Magnolia Pictures Cinetic Media MPRM Communications (212) 924-6701 phone [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 49 west 27th street 7th floor new york, ny 10001 tel 212 924 6701 fax 212 924 6742 www.magpictures.com SYNOPSIS In 1979, James Baldwin wrote a letter to his literary agent describing his next project, Remember This House. -

Haiti and the Jean Dominique Investigation: an Interview with Mario Joseph and Brian Concannon

136 The Journal of Haitian Studies, Vol. 13 No. 2 © 2007 Jeb Sprague University of Manchester Haiti and the Jean Dominique Investigation: An Interview with Mario Joseph and Brian Concannon On April 3, 2000, Jean Dominique, Haiti’s most popular journalist, was shot four times in the chest as he arrived for work at Radio Haïti. The station’s security guard Jean-Claude Louissant was also killed in the attack. The President of Haiti, René Préval, ordered three days of official mourning and 16,000 people reportedly attended his funeral. A documentary film released in 2003, The Agronomist, by Academy Award-winning director Jonathan Demme featured Dominique’s inspiring life. However, since Dominique’s death the investigation into his murder has sparked a constant point of controversy.1 Attorneys Mario Joseph and Brian Concannon worked for the Bureau des Avocats Internationaux (BAI), a human rights lawyer’s office supported by both the Préval and Aristide governments. The BAI was tasked with helping to investigate the killings. A discussion with the two attorneys reveals the unpublished perspective of former government insiders who worked on the case and their thoughts on the role of former Senator Dany Toussaint, the investigation headed by Judge Claudy Gassant, the mobilization around the case, and recent revelations made by Guy Philippe, a leader of the ex-military organization Front pour la Libération et la Réconstruction Nationales (FLRN). This interview was conducted over the telephone and by e-mail during April and May of 2007. Haiti and the Jean Dominique Investigation 137 JS: It has been seven years since Jean Dominique was killed. -

Moloch Tropical Ou Le Film Politique En Haïti

Haïti en Marche, édition du 08 au 14 Septembre 2010 • Vol XXIV • N° 33 HIER & AUJOURD’HUI Moloch Tropical ou le fi lm politique en Haïti PORT-AU-PRINCE, 1er Septembre – Le ci- ‘L’homme sur les quais’ et ‘Lumumba’) a réalisé un dernier Selon différents articles parus à l’extérieur, ‘Mo- néaste haïtien Raoul Peck (plus connu comme l’auteur de fi lm intitulé ‘Moloch Tropical’. loch Tropical’ – qui n’a pas encore été projeté en Haïti - est l’histoire d’un dictateur et celui-ci aurait des traits marquants avec l’ex-président et prêtre Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Nous n’avons pas encore vu le fi lm et ne saurions (CINEMA /p. 6) Dans le rôle du dictateur haïtien surnommé Moloch, l’acteur Zinédine Soualem, et assise au fond la touchante Sonia Rolland Papa Doc recevant une mission militaire américaine VIOLENCES ET DROGUE Elections : Qui a la légitimité comme La sécurité demeure candidat du parti présidentiel ? fragile en Haïti à PORT-AU-PRINCE, 4 Septembre – C’est la le lui interdit. Mais les candidats eux-mêmes hésitent à se veillée d’armes. Qu’est-ce qui domine l’actualité ? Les lancer. Ils sont en train de délimiter leurs pieds carrés ou l'approche des élections visites du chef de l’Etat aux différents candidats à la pré- surface de réparation. Ils posent leurs banderilles comme sidence. Or le président n’est pas candidat, la Constitution (LEGITIMITE / p. 4) NEW YORK (Nations unies) - La sécurité demeure fragile en Haïti à l'approche des élections présidentielle et lé- gislatives du 28 novembre qui risquent d'être affectées par un nombre croissant d'armes en circulation et un trafi c de drogue qui se renforce, souligne mardi un rapport de l'ONU. -

Narrative ‘Trauma-Testimony’ and Fragmented Identity in Sometimes in April

Narrative ‘Trauma-Testimony’ and Fragmented Identity in Sometimes in April Soji Cole Faculty of Humanities, Brock University 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way, St. Catherines, Ontario, Canada E-mail: [email protected] This paper examines how trauma victims’ sense of self is split and how personal identity is fragmented in the course of giving testimony of the traumatic events. The film ‘Sometimes in April’ is used as a case study based on its critical engagement with different elements of narrativity of traumatic events, and the subject of identity. The paper adopts the concepts of narrative construction of the self, selfhood, and identity following the works of scholars like Ricoeur, Schechtman and Taylor. It argues that the film ‘Sometimes in April’ is an alternative sociological space for the studying and understanding of narrative and identity construction of victims and witnesses to the 1994 Rwandan genocide. Narrative, Identity, Testimony, African film, Trauma Traditionally, trauma refers to a physical and psychological phenomenon which constitute a violent disruption of the body’s integrity. It is described as an intensely painful experience in which the mental and emotional after-effects can completely alter the sufferer’s relationship and perception with the surrounding world. The unprocessed memory of the experience always remains engraved in the mind, leading to pathologies of memory, emotion and practical functioning. In the late nineteenth century, the concept began to be applied to psychological phenomena by pioneers like Sigmund Freud and Pierre Janet in their work on hysteria. Psychological trauma refers to an experience that overwhelmed a person’s normal means of mentally processing stimuli. -

Haiti Abuse of Human Rights: Political Violence As the 200Th Anniversary of Independence Approaches Context

Haiti Abuse of human rights: political violence as the 200th anniversary of independence approaches Context 1. In spite of nearly 200 years of independence, Haiti as a young democracy Haiti's largely slave population won its freedom, and the country as a whole its independence, after 13 years of struggle in which Haitians overthrew the French colonial system and defeated invading armies from France, Great Britain and Spain before declaring an independent nation on New Year's Day, 1804. In the two centuries since independence, Haiti has undergone a nearly unbroken chain of dictatorships, military coups and political assassinations. The first peaceful handover between democratically -elected leaders in the country's history took place in February 1996, when President Jean Bertrand Aristide, having spent over three years of his term in exile following a coup and returning to office only after an international military intervention, stepped down to make way for President René Préval. After this promising start, the administration of President Préval quickly became mired in difficulties which hampered its ability to govern. In June 1997 the Prime Minister, Rosny Smarth, resigned following allegations of electoral fraud. The mandates of nearly all of the countrys elected officials, including local and legislative officers, expired in January 1999, before elections had been held for their replacements. President Préval did not extend the sitting officials' mandates, beginning instead a period of rule by decree. Three days later, the vacant post of Prime Minister was filled by a candidate whose nomination had been previously approved by Parliament, but whose cabinet and government programme were not. -

In Solidarity Anti-Racism Training Bibliography, Resources & Digital References

1 In Solidarity Anti-Racism Training Bibliography, Resources & Digital References Compiled by Deacon Joan Crawford for St. Philip’s in the Hills Episcopal Church-Jan 2021 BOOKS Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference, 2011. Anderson, Carol. (2020). WHITE RAGE the unspoken truth of our racial divide; the unspoken truth of our racial divide. S.l.: BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING PLC. Baptist, Edward E. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. Basic Books, 2016. DiAngelo, R. (2019). White fragility: Why it's so hard for white people to talk about racism. London: Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books. Kendi, I. X. (2017). Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. New York: Nation Books. Reynolds, J., & Kendi, I. X. (2020). Stamped: Racism, antiracism, and you. New York: Little, Brown and Company. King, Martin Luther. A Letter from a Birmingham Jail. Publisher not identified, 1968. Rothstein, Richard. The Color of Law: a Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing Corporation, a Division of W.W. Norton & Company, 2017. Stevenson Bryan. Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption. Spiegel & Grau, 2015. Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Paw Prints, 2010 (Anchor Books, 2008) Wilkerson, Isabel. The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of Americas Great Migration. Random House, 2010. Wilkerson, I. (2020). Caste: The origins of our discontents. New York: Random House. Rev. Joan Crawford [email protected] FILMS 13th by Ava DuVernay only available on NETFLIX Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities by Stanley Nelson; on PBS I Am Not Your Negro by Raoul Peck available on Prime, Netflix and other outlets The Hate U Give – written by Angie Thomas. -

Latin America/Caribbean Report, Nr. 21

CONSOLIDATING STABILITY IN HAITI Latin America/Caribbean Report N°21 – 18 July 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. SECURITY...................................................................................................................... 1 A. PROGRESS.............................................................................................................................1 B. REMAINING FRAGILITY .........................................................................................................3 III. CONSOLIDATING STABILITY IN PORT-AU-PRINCE: CITÉ SOLEIL............ 5 A. LESSONS LEARNED FROM EXTERNAL ASSISTANCE ...............................................................5 B. COORDINATION AND JOB CREATION CHALLENGES ...............................................................6 C. LOCAL SECURITY AND JUSTICE CHALLENGES .......................................................................8 D. THE COMMUNE GOVERNMENT..............................................................................................9 IV. GOVERNANCE AND POLITICAL REFORM........................................................ 10 A. THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCENE ......................................................................................10 B. PARLIAMENT.......................................................................................................................11